the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The contested environmental futures of the Dolomites: a political ecology of mountains

In recent years, the eco-climate crisis has intensified the institutional debate on sustainable environmental futures and the need to boost green transition policies. Scholars in critical geography and political ecology have discussed the controversial nature of these policies and argued that structural transformation is needed, focused specifically on environmental conservation. However, little attention has been paid to mountain environments, which today are significantly affected by the eco-climate crisis and characterized by controversial trajectories of development, conservation and valorization. Therefore, by bringing together the political ecology of conservation and mountain geographies, this contribution reflects on the environmental futures of the Dolomites, in the eastern Alps, through an analysis of governance processes, conservation visions and rising environmental struggles. The Dolomites show the contested nature of environmental futures and their politicization, between ideas of accumulation by sustainability and radical environmental visions. Moreover, they encompass experiences and practices that envision a convivial conservation perspective with the potential to advance the political ecology of the mountain, with specific reference to the Global North.

- Article

(3389 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

In the framework of the global eco-climate crisis, in the last decade critical geography and political ecology scholarship has critically questioned environmental governance policies and especially the imperative of green growth. First, such perspectives have critiqued the technocratic nature of global governance and its logic of capital extractivism through nature, and second, these two branches of scholarship have argued the need to radically reconfigure socio-environmental politics in the direction of justice and advance a post-capitalist perspective (Swyngedouw, 2011; Bryant, 2017; Benjaminsen and Svarstad, 2021). Within political ecology discussions on environmental change, in recent years a consideration of radical conservation politics and practices has become central to the debate on post-capitalist perspectives directed at radical environmental futures (Büscher and Fletcher, 2020). However, little research has considered these processes in mountain environments, settings that are severely affected by the effects of the eco-climate crisis and characterized by controversial processes of conservation, valorization and development (Stoddart, 2013; Vasile and Iordachescu, 2022). Indeed, a recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report classified mountains, and especially the Alps, as a hotspot of climate change (IPCC, 2022). Whereas scholars of mountain geographies have focused on mountain governance for sustainable development, mountain–urban area relations, tourism dynamics and the role of local communities, there is a lack of research on power relations, environmental struggles and potential, contested mountain futures (Debarbieux and Price, 2008; Sarmiento, 2020). There is thus a need to critically reflect on mountain environmental visions and ideas and politics of transformation in mountain areas to fill this gap. Indeed, the perspective of political ecology, and especially its critical stance on conservation, has the potential to advance the reflection on the sociopolitical production of the mountain environment and its futures in relation to the eco-climate crisis.

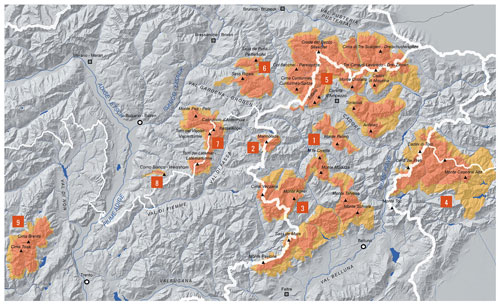

By adopting a political ecology perspective and focusing on radical conservation proposals, this paper reflects on mountain environmental futures through an analysis of governance processes, conservation visions and rising environmental struggles in the Dolomites, located in the southeastern alpine region of North Italy. Within the political ecology of conservation debate, the convivial conservation framework offers a window of observation onto the complex interplay of ideas, visions and interests that revolve around environmental change and particularly future prospects for change. In considering mountain regions in the Global North, the Dolomites represent a key case study given that, on the one hand, this range has been deeply affected by the eco-climate crisis in terms of average annual temperatures, extreme events, biodiversity loss and glacier melt in recent years. On the other hand, it has also experienced a significant increase in tourism appeal due to UNESCO heritage recognition, mountain infrastructural development and by the 2019 assignment of the Milano–Cortina 2026 Olympics. These intertwined dynamics have given rise to a debate and struggles between institutions and members of local communities regarding the Dolomites' present and future in terms of socio-environmental relations, governance and politics. Therefore, it is important to first analyze transcalar governance and its power dynamics together with conservation visions; second, to understand the controversial interests and struggles between actors with regard to mountain infrastructural development initiatives, especially those linked to the Milano–Cortina 2026 Olympics, and environmental futures. In terms of methods, this research adopts an ethnographic perspective together with a literature review ranging from mountain geographies to the political ecology of conservation as well as policy papers and dissemination articles. Ethnographic investigation in the Dolomites included formal and informal conversations and semi-structured interviews with mountain experts and academics, members of institutions at different scales, mountain lift companies, and social actors such as the representatives of sociocultural, environmentalist and mountain associations. Ethnographic research and field surveys were carried out from February to November 2022 in the central area of the Dolomites from Bolzano and the Gardena and Fassa valleys to the Belluno, Alto Agordino and the Ampezzo valleys. These methods, together with a critical reflection on governance, conservation and struggles, have enabled the research to make two main contributions: first, to strengthen the dialogue between political ecology of conservation and mountain geographies and question the narrative of sustainable development and local community involvement often highlighted by scholars in mountain geographies (Balsiger and Debarbieux, 2015; Perlik, 2019; Varotto, 2020) and, second, to better understand contested environmental futures and more effectively explore the visions and experiences that envision convivial conservation principles (Büscher and Fletcher, 2020) directed at advancing the political ecology of the mountain, with regard to the Global North. Indeed, it is important to further develop this perspective to achieve a deeper understanding of the contested, controversial, conflicting and uneven socio-environmental processes that characterize mountains in terms of conservation, community rights and justice, capital valorization, infrastructural development, tourism, and resource commodification policies, especially under conditions of the eco-climate crisis (Kumar Sharma et al., 2010; Stoddart, 2013; Vasile and Iordachescu, 2022). The next section provides a theoretical overview of the political ecology perspective and contemporary conservation debates, especially convivial conservation, in dialogue with mountain geographies. The subsequent section focuses on the Dolomites and analyzes governance mechanisms, conservation visions and rising struggles around mountain development initiatives. The paper then discusses and emphasizes the contested environmental futures of the Dolomites, particularly in relation to divergent and conflicting mountain visions. The conclusion highlights the repoliticization of mountain futures and discusses radical initiatives and practices that contribute to reflections on convivial conservation principles with the potential to advance the perspective of the political ecology of the mountain in the Global North.

2.1 The political ecology of conservation and the convivial conservation vision

Over the last few decades political ecology scholarship has provided a key contribution to critically questioning capitalist accumulation processes, especially human domination of the environment rooted in the mainstream vision of a society–environment dichotomy (Smith, 1984; Castree, 2003; Robbins, 2012; Perreault et al., 2015; Kothari et al., 2019). Indeed, as Bryant et al. (2017), Benjaminsen and Svarstad (2021) and others have highlighted, the environment can instead be seen as a contested socio-natural product that is caught up with divergent and uneven visions, powers and interests. Therefore, with regard to today's eco-climate crisis, political ecology perspectives argue that we must necessarily rethink human–environment relations in the direction of pursuing more just environmental futures through transformative change (Kothari et al., 2019).

This argument has been recently advanced in the debate regarding environmental conservation in, and beyond, the Anthropocene. Critical perspectives find that mainstream neoliberal conservation has been instrumental to capitalist growth and reproduction: Brockington et al. (2008) and Büscher (2012) stress that neoliberal conservationists have self-presented as defenders of nature, but, in reality, their conservation vision should be seen as a strategy by which capitalism is able to monetize natural resources, preserving them as “natural capital” for so-called non-consumptive use rather than resource-extracting resources. Critical reflection on these processes, and especially forest conservation and carbon trading markets, has led Büscher and Fletcher (2015) to propose the idea of “accumulation by conservation” as a specific strategy of accumulation that takes the negative environmental contradictions of contemporary capitalism as its point of departure for defining a new, “sustainable” model of accumulation for the future. Furthermore, mainstream neoliberal conservation continues to cling to a society vs. environment dichotomy by promoting protected areas in order to extract capital value through the protection of nature in conjunction with participatory approaches and community-based governance. In recent years, a range of proposals have been launched to reconfigure conservation politics and practices: the two most prominent are the new conservationist and the neo-protectionist perspectives (Kareiva et al., 2012; Wilson, 2016). Despite their aim of advancing novel conservation perspectives to deal with the eco-climate crisis, however, these proposed approaches have been called into question for not sufficiently addressing the issues of contemporary conservation that have contributed to fueling injustice, extractivism focused on natural materials and capital accumulation. Indeed, scholars focused on the political ecology of conservation have stressed the key importance of two issues: the relationship between society and the rest of nature in terms of coexistence and the position of conservation with regard to the unsustainable political economy of neoliberal capitalism (Cavanagh and Benjaminsen, 2017; Bluwstein, 2018; Büscher and Fletcher, 2020). Büscher and Fletcher (2020) have emphasized that none of the new conservationist and neo-protectionist perspectives promise to ensure the key structural transformations needed to deal with the climate crisis and, therefore, that pursuing more just environmental futures would require a radically transformative vision for conservation.

The proposal Büscher and Fletcher (2020) make is “convivial conservation”, a vision and set of governance principles that move beyond capitalism, market-based principles, the nature–society dichotomy and a central focus on protected areas. Rather, this perspective aims to reconnect society and nature across scales, space and times in the direction of hybrid conviviality, to boost the de-accumulation of resources and curb capital extraction, and to promote structural change and equity in a framework of environmental justice (Büscher and Fletcher, 2020). Since convivial conservation is conceptualized as a theory of transformative change aimed at politicizing conservation, it seeks to analyze and deal with governance actors, politics, power relations and temporality with the aim of fostering radical reformism in the short term and structural transformation in the longer term. In an effort to advance convivial conservation theory and practices, Vasile and Iordachescu (2022) and Toncheva et al. (2022) have recently discussed the potential of radical change in European conservation governance to move us towards convivial transformation by looking at forest commons in Romania and human–non-human coexistence in Bulgaria. Specifically, Vasile (2019) and Iordachescu (2022) have explored convivial conservation proposals in Europe by looking at existing commons land and especially the Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas (ICCAs) supported by the work of the ICCA consortium. Taking the case of Romanian forest commons, Iordachescu (2022) argues that these initiatives could offer examples of a transition pathway leading towards more just and democratic conservation based on convivial conservation principles.

Research on convivial conservation and the political ecology of the conservation debate thus offers potential insights for reflecting productively on environmental futures and possibilities for change. While political ecology of conservation scholarship has focused extensively on protected areas in regions of the Global South such as sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America (Marijnen et al., 2021; Bluwstein, 2018), however, little attention has been paid to conservation politics in mountain areas, especially in the Global North (Iordachescu, 2022; Toncheva et al., 2022). Therefore, this research aims to shed light on these processes by bringing a political ecology of conservation lens to bear on mountain geographies and, in particular, exploring the Dolomites' environmental futures.

2.2 Mountain geographies and political ecology in dialogue

Geography has long displayed a fascination with mountains, with the earliest research conducted mostly by German, Austrian and Swiss geography scholars focusing on relationships between socioeconomic activities and the natural environment, the impact of tourism, and relations between mountain populations and their environment (Ives and Messerli, 1990; Forsyth, 1998; Funnel and Price, 2003). Indeed, as discussed by Rudaz (2011), mountains appeared for the first time in a 1992 intergovernmental declaration at the Rio conference, and chapter 13 of Agenda 21, the Mountain Agenda, recognized mountains as a global common good and formalized the aim of promoting sustainable mountain development. This recognition inspired the Alpine Convention as well as the Mountain Partnership in 2002. Over the last few decades, Swiss and French geography, and especially Bernese scholarship, has addressed sustainable mountain use in different settings on a global scale with the aim of merging research on mountain social and ecological systems, as noted by Messerli and Rey (2012). Debarbieux and Price (2008) and Perlik (2019) have integrated this perspective by highlighting the globalization of mountain issues and transcalar mountain policy-making and relationships between global socioeconomic transformations and mountain development. The evolution of this field has recently been further advanced by American mountain geography scholarship, and by Fonstad (2017) and Sarmiento (2020) in particular, with the analysis of mountains as regions that are highly sensitive to climate change, hazard and risk. In parallel, Italian mountain geography, by focusing on the Alps, has discussed relations between mountain and metropolitan areas and the urban construction of mountain spaces, as well as processes of socioeconomic marginalization (Dematteis, 2018; Varotto, 2020). On the other hand, mountain geographers have analyzed the impact of tourism, communities and identities, as well as inclusive governance processes aimed at strengthening sustainable mountain development and granting mountain regions new socioeconomic centrality (Pascolini, 2008; Ferrario and Marzo, 2020). Other scholars such as Favero et al. (2016) and Dalla Torre et al. (2022) have contributed to mountain studies by reflecting on the role of collective resource ownership in mountain areas, their role in mountain governance and socioeconomic transformations, and their importance for sustainable mountain development.

Although mountain geography has been widely debated in these bodies of scholarship, however, such research has mostly adopted an uncritical approach to the concept of mountain nature, its governance processes and development. Indeed, when reflecting on today's debates about the environment, most mountain geography literature continues to reproduce a society–environment dichotomy perspective without considering long-established critical approaches that view the environment as sociopolitically produced (Castree, 2003; Loftus, 2017; Büscher and Fletcher, 2020). Indeed, contemporary mountain geography research lacks a critical reflection on how transcalar power dynamics – in terms of uneven relations and actors' bargaining power – affect the sociopolitical production of the mountain environment, as well as the political dimension of conservation and sustainability which might include divergent visions and contestation. Furthermore, an analysis of environmental struggles is still lacking from contemporary mountain geography research even though critical geography and political ecology have long discussed this topic (Perreault et al., 2015; Zinzani and Curzi 2020). Moreover, despite the ongoing discussion of alpine collective resource management advanced by Favero et al. (2016) and Dalla Torre et al. (2022) among others, the literature has yet to devote significant attention to their potential role in fostering transformative change towards more just environmental futures.

The contribution of political ecology, and especially its approach to conservation, could thus help fuel reflection on the sociopolitical production of the mountain environment and its futures, particularly in the Global North. Hence, the notion of mountain environmental futures could advance our understanding of the complex interplay among governance mechanisms, as well as divergent interests, conservation visions and potential conflicts related to environmental change.

This perspective, applied to the Alpine context of the Dolomites, will therefore provide an important contribution to mountain geography scholarship for two main reasons: because the eco-climate crisis is having severe effects on the Dolomites' socio-environmental relations and because this context is characterized by controversial and contested pathways of conservation, infrastructural development and capital valorization. Indeed, contested Dolomites environmental futures prove a key object of analysis, first to delve more deeply into the potential of convivial conservation in mountain areas (Toncheva et al., 2022; Iordachescu, 2022) and secondly to fill the gap in political ecology scholarship regarding mountain areas, especially in Europe. Focusing on the Global South and specifically on the Himalayas, Kumar Sharma et al. (2010) have explored the intersection of tourism intensification, indigenous rights and sustainable mountain development, and Mukherji et al. (2019) have analyzed politics and power with regard to the cryosphere service to communities, while Kovács et al. (2019) have highlighted water access inequalities and conflicts in mountain towns. In the same vein, looking at Global North mountains, Stoddart (2013) has investigated the ecopolitics of snow and the role skiing plays in producing mountain socio-natures in the United States, while Vasile and Iordachescu (2022) and Voicu and Vasile (2022), although not explicitly positioning their work in political ecology, have recently discussed formal and informal forest logging, power relations and the role of collective properties in Eastern European mountains. Therefore, the case of the Dolomites could contribute to advancing knowledge in political ecology with a focus on the mountain perspective.

3.1 The eco-climate crisis in the Dolomites

In recent years, IPCC climate science experts have stated that mountains are one of the environments most vulnerable to the effects of the global eco-climate crisis (IPCC, 2022). A climate expert of the Centro Valanghe di Arabba (Belluno) added that the Alps, and especially the Dolomites, are facing more severe climate change challenges than the lowlands of central-southern Europe in terms of global warming, biodiversity loss and environmental degradation. The Dolomites are part of the southeastern section of the Alps in northeastern Italy and include several peaks of over 3000 m up to the 3343 m high Marmolada, tiny glaciers, alpine meadows and forests, agricultural and pasture areas, and small towns and villages.

This range has been facing climate change effects since the 1980s, but this trend has intensified over the past two decades with a significant increase in average annual temperatures leading to a decrease in snowfall and winter snow cover and a surge of extreme events including heavy rainfall, storms and falling trees, such as Storm Vaia in autumn 2018. Indeed, heat waves and drought are also contributing to forest degradation and biodiversity loss by favoring the spread of the Bostrichidae beetle, an insect that is killing off thousands of hectares of red spruce forest (Lasen, 2022). Higher temperatures and heat peaks are also accelerating the trend of glacial melt, and the Dolomites' glaciers are quite exposed due to their small overall size and low altitude. Furthermore, the summer 2022 heat wave and drought led to water scarcity issues, both at high altitudes and in valleys.

Therefore, the effects of the eco-climate crisis on the Dolomites recently gave rise to a public debate on tourism attraction and the need to diversify tourism in this area, especially by emphasizing alternatives to skiing in view of snow availability issues and environment–development interactions. Indeed, although tourism has been the most important factor driving development and economic growth since the 1970s, the 2009 declaration of the Dolomites as a UNESCO world heritage site, and more recently the post-pandemic context, has entailed significant growth in national and international tourism (Ferrario and Marzo, 2020). These developments have led to initiatives focused on building new infrastructure such as lifts and resorts, mainly proposed by institutions and private companies. The Carosello Dolomitico project, for instance, is also driven by the World Ski Championships 2021 held in Cortina and the political–economic dynamics surrounding the Milano–Cortina 2026 Olympic organizational processes (Casanova, 2020). Efforts to promote these projects have kindled more intense reflection on the Dolomites' environment, local conservation policies and economic valorization and boosted local debates among institutions, local communities and associations. It is therefore strategically important to shed light on governance mechanisms in this area and especially actors' ideas and visions of conservation.

3.2 Governance mechanisms and conservation visions

The Dolomites territory extends across two regions, Trentino-Alto Adige and Veneto, and three provinces, Trento (TN), Bolzano (BZ) and Belluno (BL). Whereas Trentino-Alto Adige is an autonomous mountain region that includes the two autonomous provinces of Bolzano and Trento, in Veneto only the Belluno province is part of the Dolomites. This institutional fragmentation rooted in Italy's post-World War I historical and political legacy has differentiated the Dolomites' political–economic development trajectories over the last few decades. Bolzano and Trento have greater economic power due to their autonomous status and are wholly included in the mountains; Belluno province, for its part, has denounced this political–economic asymmetry and the fact that Venice exerts regional political control. According to a member of the Belluno provincial government, this governance fragmentation and Bolzano and Trento's autonomy in terms of political–economic development has exacerbated uneven power relations among the provinces. The head of the Ladin sociocultural center argued that the Veneto-region central powers, located in Venice, have never been able to fully understand mountain communities' issues and claims. Whereas Bolzano and Trento have anchored their development in tourism and intensive agricultural and pastoral activities over the last few decades, Belluno has prioritized industrial and hydropower development in the valleys, agriculture, and forestry with less focus on tourism.

The Dolomites' environmental governance framework also includes natural parks that were established in the 1960s: while in Bolzano provincial parks are centrally managed by the government, in Trento management is more decentralized in that it includes representatives of municipalities and local communities; in Belluno province, the natural park has been managed since the 1990s by a collective entity, the Regole d'Ampezzo. In addition to natural parks, the Fondazione Dolomiti UNESCO, a non-profit organization established by Dolomites regional and provincial institutions together with the UNESCO secretariat, was set up in 2009 to govern, conserve and valorize the natural heritage of the Dolomites (mainly peaks and high-mountain meadows in specific selected areas); address provincial institutions' environmental initiatives; and limit potential disagreement among the actors and their visions.

At the local scale, governance includes municipalities and, in some parts of Belluno and Trento provinces, two kinds of collective property-owning unions called regole and usi civici (Dalla Torre et al., 2022). For centuries, such collective property owners have played a significant role in local environmental governance as institutional actors due to their collective ownership and management of resources such as forests, pastures and meadows. They have also modeled a form of communal, grassroots conservation rooted in local communities. The resource management and conservation practices of collective property unions are usually similar, but their visions are quite heterogeneous and end up being shaped by local socioeconomic dynamics and relations with other actors, particularly municipalities. Whereas municipalities design and implement planning documents for valley floors and mountain slopes, collective property owners such as Regole d'Ampezzo and usi civici have historical and traditional natural resource governance regulations that are rooted in the rights and relations that have customarily been used in the community. Indeed, as stated by a member of Regole d'Ampezzo, collective properties represent examples of grassroots participatory democracy, rooted in assembly and commoning practices and aimed at governing the environment by adopting a grassroots community conservation vision. Relations between municipalities and collective property owners vary from more collaborative to more contested depending on the local historical sociopolitical legacy, control over resources and economic interests. The municipality and usi civici collective property union in the Canazei area enjoy a cooperative relationship and regole in the Campiglio area even co-manage ski resorts. The Regole d'Ampezzo in Cortina has instead had conflict-ridden relations with the municipality for some time now due to political competition in terms of supporting community interests and conflicting positions in negotiating with powerful private actors that have become more acute in relation to the World Ski Championship 2021 and Milano–Cortina 2026 Olympics. Indeed, one Regole d'Ampezzo member argued that the existence of and role played by Regole d'Ampezzo have prevented massive speculation-based urbanization in the valley, especially since the 1970s, and contributed to mountain environmental and biodiversity conservation. In the private sector, mountain ski lift companies such as the Dolomiti Superski consortium, Dolomiti Rete and a number of other private entities play a key role in environmental and infrastructural development relations thanks to their significant bargaining power with institutions at different scales. Looking at civil society more broadly, mountain organizations, hut managers and sociocultural associations (especially environmentalist ones) also hold important positions in the Dolomites' environmental governance due to their range of activities and relations with institutions.

The various territories of the Dolomites are characterized by multiple different perspectives on and visions of conservation at different scales. As highlighted in conversations with different institutional and social actors, the conservation perspective prevailing in Bolzano province is one of human domination and control over the environment. A legacy of the area's Hapsburg cultural and historical past, this perspective emphasizes forest and pasture management, logging, and intensive agriculture in mountain areas. The Bolzano province's vision of the environment, rooted in human domination and control, has had a significant impact on biodiversity loss. Indeed, a representative of the green party argued that, despite the provincial government's narrative about environmental awareness and sustainability, institutions have co-produced a highly human-shaped environment over the last few decades reflecting the interests of intensive agriculture and attracting tourism. In Belluno province, in contrast, socio-environmental relations are more balanced, human control over the environment is less intense due in part to the province's socioeconomic trajectory and use of lowland migration, and processes of pasture and forest rewilding are supported by institutions and discussed with local community members. Trento province instead shares the perspective of Bolzano combined with a more decentralized structure, and its approach is characterized by less intense forest and pasture control as well as re-naturalization processes.

Regarding biodiversity specifically, provincial institutions have affirmed their common commitment to conservation by setting up Natura 2000 protected areas and natural parks. Natura 2000 areas, inspired by the Habitat directive and a protectionist perspective, are found in multiple Dolomites provinces and differ in terms of governance: whereas in Bolzano and Belluno they are coordinated by provincial governments, in Trento the networks of natural reserves were established by municipalities to be managed under the Natura 2000 framework. The research found divergent perspectives on these protected areas: whereas the head of the Belluno provincial department of nature argued that Natura 2000 is the most effective example of conservation and the province displays its commitment to environmental protection with 56 % coverage, the director of the Dolomiti d'Ampezzo natural park instead stated that these areas are important for protecting specific biotopes but play a limited role in addressing the environmental crisis more broadly.

In addition to Natura 2000, provincial natural parks are the most widespread type of protected areas in the Dolomites. Natural parks have been established since the 1970s to boost environmental conservation and encourage sustainable socio-natural interactions while providing environmental education and attracting tourism. In Bolzano province, protected areas are centrally managed by the provincial nature office, while in Trentino governance is more decentralized and also involves municipalities, local community members and environmentalist associations. In Belluno, the Dolomiti d'Ampezzo natural park is instead managed by the Regole d'Ampezzo, based in Cortina. The Veneto region entrusted this park's governance to the Regole d'Ampezzo because the property union has owned the park area for centuries and contributed to forest and pasture governance and environmental conservation by serving as a collective actor and holding meetings. Indeed, the director emphasized that community has a key role to play in conservation, stressing in particular that a shared vision is needed to successfully move beyond a protectionist society–environment divide and promote community-based socio-environmental integration in conservation. Except for the Dolomiti d'Ampezzo natural park, however, these protected areas do not show significant differences in terms of their prevailing conservation visions regardless of institutional differences in governance; indeed, Dolomites-area natural parks generally merge ideas of mainstream and community conservation, adopting visions rooted in a society–environment dichotomy and promoting various narratives ranging from forest conservation and environmental valorization to ecotourism. Although natural parks were established to ensure environmental education and attract tourism, however, a member of the association Mountain Wilderness argued that, despite the importance of thinking beyond the logic of protected areas to advance new ideas in conservation, parks are still strategic in preventing the construction of new mountain infrastructure such as ski facilities and hydropower projects. This position was also expressed by the Bolzano provincial green party, which added that conservation needs to be conceived in a different way by moving beyond the society–environment dichotomy.

The last two decades have witnessed green parties and various environmentalist associations pushing for more Dolomites-area environmental conservation and collaboration on the managing boards of protected areas, and this involvement played a significant role in securing the Dolomites' UNESCO recognition in 2009. However, while environmentalist associations since the 2000s have called for protecting the Dolomites' environment as landscape and cultural heritage, in the end governance institutions applied for geological natural heritage recognition in specific selected areas, mainly coinciding with already established protected areas so as to facilitate future governance. It is important to stress that the move to opt for geological heritage status, applied exclusively to peaks and high-altitude meadows, was a political choice and one that facilitated transcalar political negotiations regarding the designation of new protected areas while reproducing a clear society–environment separation. Indeed, with the approval of UNESCO international officials, an archipelago of nine Dolomites groups was designated and the Fondazione Dolomiti UNESCO established with an administrative council that included representatives of provincial institutions. On the one hand, Fondazione Dolomiti UNESCO was established to govern the conservation and valorization of Dolomites-area natural heritage in core and buffer areas of the archipelago. On the other hand, it also seeks to coordinate the various environmental visions of provincial institutions as well as their divergent interests. However, UNESCO recognition does not involve legally binding mechanisms, and therefore the Fondazione Dolomiti UNESCO does not have the legislative power to shape institutional politics. Since 2014, the Fondazione Dolomiti UNESCO has been working to boost public involvement in order to strengthen community participation and design a shared governance strategy called Dolomiti 2040. Bringing together provincial and municipal officials and members of mountain, environmentalist and cultural associations, this process was guided by the idea of encouraging active conservation characterized by principles of bottom-up valorization, education and sustainability, not only in the UNESCO site but also as a shared conservation vision for the entire Dolomites' environment. However, the varying interests of the actors involved have conditioned their support for and adoption of these principles: several mayors have argued that the Fondazione Dolomiti UNESCO is quite weak in balancing diverging interests between provincial institutions and limiting the bargaining power of mountain lift companies, while at the same time it has proved effective in promoting and marketing tourism through the UNESCO label. Indeed, representatives of cultural and environmentalist associations claim that the Fondazione Dolomiti UNESCO has not been able to raise environmental awareness and are quite critical about the choice to apply UNESCO heritage principles only to buffer and core areas rather than the territory as a whole. Moreover, national and local environmental associations deeply critique the Fondazione Dolomiti UNESCO for its weak bargaining role in relation to new lift construction, water reservoirs and resort development, often planned by mountain lift companies with the support of provincial institutions close to or even inside UNESCO buffer areas. Mountain Wilderness, together with other environmentalist and cultural associations, stopped collaborating with the Fondazione Dolomiti UNESCO in 2019, denouncing the failure to implement the Dolomiti 2040 Strategy and especially the Fondazione Dolomiti's conciliatory attitude towards mountain lift companies and institutional powers, in particular around the contested organizational process of the Milano–Cortina 2026 Olympics (Casanova, 2020). The Regole d'Ampezzo has emphasized UNESCO's controversial role, pointing out that the lack of legally binding mechanisms makes it weak especially when negotiating around mountain infrastructural development but powerful when promoting tourism development marketing strategies.

3.3 Mountain infrastructural development and the rise of environmental struggles

Over the last few years, mountain lift companies such as Dolomiti Superski and Rete Dolomiti, among others, have pushed for infrastructural projects such as new lifts and intra-valley ski connections, often with the support of regional and provincial institutions. In an effort to legitimize their initiatives in relation to the eco-climate crisis, these actors were able to advance an authoritative discourse centered on environmental awareness, sustainable mountain development visions and the aim of using their projects to foster sustainable mobility. Nonetheless, a heterogeneous network of dissenters has formed to call into question these projects and their discourses and, especially, to propose a radical change in mountain development pathways. Such counterclaims arose around the organization of the World Ski Championships 2021 in Cortina, the establishment of Fondazione Milano–Cortina 2026 to organize the Olympics and the launch of the Carosello Dolomitico project by the Veneto region. Organizing the world ski championships entailed extending ski slopes, renovating lifts and creating reservoirs to store water. Milano–Cortina 2026 and Carosello Dolomitico, on the other hand, currently represent the most strategic initiatives in terms of infrastructural development. With regard to the Olympics, three main projects are planned in the Cortina valley. The first involves building two new lifts to connect Cortina with the Tofane (Socrepes) and Faloria ski resorts. The facilities in this case would be constructed on an unstable slope that had been deliberately protected from urban development, as stressed by a former member of the regional forests department. The second project is the Olympic village to be built in the valley floor north of Cortina, an ecologically fragile area characterized by hydrogeological risk as highlighted by the director of Regole d'Ampezzo. The most controversial project, however, is the bobsled slope planned to replace the existing slope built in the 1950s. This project will cost approximately EUR 100 million and require razing three hectares of forest, as well as the construction of new infrastructure such as a pumping station to divert water from the river to cover the slope in ice.

The second strategic initiative is the Carosello Dolomitico, promoted since 2020 by the president of Veneto region in the wake of the 2021 World Ski Championship. The aim of the Carosello, conceived as an intra-valley network of ski lift connections, is to link Cortina with other villages and valleys such as Arabba and Alleghe, as well as Comelico with the Sesto valley, by building long lifts and gondolas to connect and extend the Dolomites' ski area. According to its promoters, the Veneto region, Rete Dolomiti and other companies, the Carosello will boost sustainable mobility – especially in the summer – by replacing car travel. The project has been contested, however, especially by Fodom valley residents. Locals formed a committee to denounce the project's severe environmental impact on forests and high-altitude meadows, many of which are included in Natura 2000, and to highlight the need to preserve the area's historical and cultural heritage from new infrastructure construction. Nearby, the Marmolada glacier has been for decades a core area for ski lift business interests to extend the ski area and develop new connections. Indeed, although the Marmolada glacier is included in the UNESCO heritage area with its ban on new construction, until the tragic serac fall of July 2022 there were discussions about building a lengthy new facility to link the village of Canazei to the top of Marmolada. In addition, multiple luxury resorts and mountain hut extensions have been planned in high-altitude meadows such as Passo Giau and the Catinaccio area, near the edge of the UNESCO heritage buffer area.

It makes strategic sense to reflect on the role played by the actors behind these projects and specifically their power relations and visions of local environmental futures. With regard to the Cortina Olympics, the Fondazione Milano–Cortina 2026 and Infrastrutture MI-CO 2026 are responsible for organization and infrastructural development, respectively. In addition, the Veneto region, its president Luca Zaia and tourism council member Federico Caner are playing a key role, first in terms of attracting European, state, regional and private funds for infrastructural development. Second, they are working to weaken the constraints imposed by environmental impact assessments and make them more lenient to the argument that the Olympics are nationally relevant. Third, they shape and control local Cortina politics through a top-down relationship with the city council and very limited transparency or community involvement in project development. Indeed, this lack of transparency and participation have exacerbated the already tense relations between the Cortina city council and the Regole d'Ampezzo. The planned Olympic facilities are located in the valley floor, on municipal property; however, the Regole d'Ampezzo, together with social and environmental associations, has spoken out about the lack of information surrounding the project and the city council's tendency to accommodate the interests of the Veneto region and related actors.

Therefore, the vision of the Olympics held by state and regional actors and shared by Cortina's mountain lift companies is intensely focused on attracting external capital flows, adopting the standards of international tourism and commodifying the mountains as widely as possible. Indeed, the significant bargaining power mountain lift companies enjoy in their relations with regional and national institutions has allowed them to earmark massive amounts of public funds to support private infrastructure and establish public–private partnerships for developing such facilities, not only in Cortina and around the Carosello Dolomitico project but also in Bolzano province. Especially in Bolzano, private lift companies have long-standing collaborations and powerful bargaining positions with the provincial government that have often enabled them to undermine environmental impact assessments on building new infrastructures and form partnerships to channel public funds towards their projects. Furthermore, the powerful position of such private actors has also undermined the operation of Fondazione Dolomiti UNESCO: it has recently failed to interrogate controversial projects located inside or near the natural heritage buffer area such as the Passo Giau resort and Catinaccio hut renovations. These projects, and especially the Carosello, have been legitimized by the insistence that they will contribute to sustainable mountain infrastructure, using a sustainable mobility rhetoric that somehow conceals the fact that public funds are being used for private interests. Despite the effects of climate change on snow cover and slope stability, private companies along with Bolzano provincial and Veneto regional institutions argue that there is no contradiction between environmental conservation and economic valorization and that today's climate change dynamics will not hamper the sustainable development of mountains and their communities.

Dolomites-area development initiatives, and especially the visions held by the actors pushing for such initiatives, are being questioned by an informal network of sociocultural and environmentalist associations including Mountain Wilderness, Legambiente, WWF, Libera, Italia Nostra, city council members, collective property members and protected area boards, other individuals, and local valley associations such as the FODOM committee. These emerging Dolomites environmental struggles focus first on preserving forests, meadows and high-altitude environments from new mountain lifts and artificial snow reservoirs and protecting the biodiversity threatened by both development initiatives and the effects of the eco-climate crisis. Second, they stress the need to boost community conservation by reconfiguring the governing boards of protected areas and Natura 2000 governance, invest in local agriculture and livestock farming, protect water resources from ski industry storage, and foster tourism diversification. On one hand, this network of environmental struggles is questioning top-down politics and the lack of public information available about the Cortina Olympic projects; on the other, it challenges the way Fondazione Dolomiti UNESCO often appears excessively sympathetic towards infrastructural projects aimed at fueling tourism. Regarding transcalar governance and politics, this network of environmental struggles demands more inclusion in decision-making processes and a stop to the use of public funds to support unsustainable, private ski infrastructure construction.

By analyzing governance mechanisms, conservation visions and emerging environmental struggles, we can see that the Dolomites' environmental futures are highly politicized and contested. Indeed, dynamics of politicization and contestation have been fueled by the effects of the eco-climate crisis on Dolomites-area socio-environmental relations, on the one hand, and infrastructural development initiatives, especially related to the Olympics, on the other hand. Therefore, today's Dolomites allow us to reflect on and question the acritical and depoliticized perspective on mountain sustainable development and good governance often highlighted by mountain geography scholarship (Debarbieux and Price, 2008; Fonstad, 2017; Perlik, 2019).

Dolomites governance shows uneven power relations and asymmetries between the Bolzano and Trento autonomous provinces and the Belluno unit as a result of specific historical and political legacies. At the same time, governance has been increasingly characterized in recent years by similar, shared political relations such as public–private partnerships, private actors and capital flows playing significant roles at multiple scales, from provincial to international. Whereas in Bolzano province local lift companies interact closely with the provincial government to attract public funds for joint infrastructural development projects while simultaneously undermining the constraints imposed by environmental impact assessments, in Belluno province, and especially in Cortina, massive regional and state capital flows go to support private infrastructural development and shape local politics. Indeed, this research has found that external institutional and private actors significantly affect local decision-making, especially by influencing local governance in the pursuit of their interests. These transcalar public–private partnerships have been able to push for, and in certain cases launch, infrastructural initiatives in proximity to protected areas and Fondazione Dolomiti UNESCO natural heritage buffer units in particular.

Despite the initial involvement of environmentalist associations and efforts to foster active conservation through the Dolomiti 2040 initiative, the role of Fondazione Dolomiti UNESCO remains quite weak, especially in terms of its bargaining power in relation to mountain lift companies and public–private partnership interests. Indeed, the Fondazione Dolomiti UNESCO has been struggling to balance political–economic interests and disagreements brought by various provincial institutions even while it seeks to promote a shared vision of active environmental conservation. However, more than 10 years after its establishment, multiple actors have seriously questioned Fondazione Dolomiti UNESCO's role on the ground in that it acts as a brand label for Dolomites-area economic development and has not taken a firm stand in advancing a novel vision of conservation beyond the eco-climate crisis more specifically.

By focusing on conservation in protected areas such as natural parks and Natura 2000 sites, this Dolomites case study shows that the prevailing conservation vision is largely the same across the provinces and generally characterized by a society–environment dichotomy; the only exception is the Dolomiti d'Ampezzo natural park, collectively governed by the Regole d'Ampezzo with their integrated socio-environmental perspective. The vision applied to Dolomites-area natural parks is shaped by principles of environmental protection, biodiversity conservation, valorization and education akin to the mainstream conservation principles called into question by Brockington et al. (2008) and Büscher et al. (2012), among others. Natura 2000 areas, in line with the European Habitat directive, instead reproduce a neo-protectionist approach that makes more distinct the separation between pristine nature and human activity. Beyond protected areas, collective property ownership union members point out that their conservation projects move beyond a society–environment dichotomy to promote truly sustainable resource governance, specifically in relation to the eco-climate crisis.

Indeed, today's debates about the environmental futures of the Dolomites are mainly focused on mountain socio-environmental relations outside of protected areas, especially the eco-climate crisis and ongoing infrastructural development initiatives. The Carosello project, Milano–Cortina 2026 organizational processes, planned renovation and construction in the Catinaccio and Passo di Giau areas, and projects to widen ski slopes have sharpened the debate on the society–environment dichotomy, sustainable development in mountain areas and green growth, as well as slope deforestation, resource availability and biodiversity loss issues. These phenomena also highlight the concepts of limits and value in the public debate around mountain development and capital extraction. Furthermore, power asymmetries in decision-making processes, public–private interests and community participation have also been questioned in relation to mountain development. Reflecting on the Dolomites' environmental futures in terms of the impact of the eco-climate crisis also raises the notion of temporality and especially the contrast between short-term and long-term visions.

In exploring how mountain futures are politicized, therefore, the analysis of the Dolomites context has revealed a heterogeneous array of ideas and positions that could be grouped into two divergent visions, each supported by different institutional, social and private actors. The most powerful and widespread perspective on the Dolomites' environmental future can be characterized as accumulation through sustainability and green growth. The underlying principles are reminiscent of the accumulation by conservation concept identified by Büscher and Fletcher (2015). This vision, rooted in a society–environment dichotomy, supports extracting capital and value from the environment and pursues a no-limits commodification of mountain areas. Promoted through sustainable mobility and development discourses and the argument that tourism and infrastructural development are the only way to prevent mountain depopulation, this perspective is supported by a variety of actors including provincial governments and local parties, lift companies, and the majority of municipal governing boards and tourism businesses. Therefore, despite adopting sustainability-focused rhetoric, this perspective continues to support the same kind of conservative mountain development politics that have characterized the last four decades notwithstanding the effects of the eco-climate crisis.

Over the last few years, this perspective – defined by environmentalists and sociocultural associations as an “assalto alla montagna”, assault on mountains – has been cast into doubt. Critics instead favor a growing vision of political change aimed at moving beyond the questionable concept and discourse of sustainability. This latter vision highlights the importance of limiting growth, in view of the eco-climate crisis, and the need to rethink the notion of value, shifting from endless capital accumulation to a focus on environmental value conceived in post-capitalist terms. Indeed, it proposes going beyond the society–environment dichotomy towards a more balanced integration of human and non-human natures in a framework of transformative change. Furthermore, this vision, supported by the local network of environmentalist associations, mountain and sociocultural organizations, climate experts, collective property union participants, and a growing number of municipal council members, aims to democratize Dolomites-area environmental governance and to support commoning and grassroots community mountain conservation. Looking at these contested future visions, we also see conflicting ideas of temporality in relation to the eco-climate crisis: on the one hand there is a short-term perspective of accumulation by sustainability and commodification despite climate change challenges, while on the other hand there is a long-term vision of transformative change, shifting from sustainability discourses toward environmental care.

The analysis of contested Dolomites' environmental futures with their conflicting ideas, interests and temporalities thus enables us to highlight the politicization of mountain futures and consider alternative experiences and practices that seek to bring about transformative change in dialogue with the vision of convivial conservation. Such a reflection serves to advance the perspective of political ecology scholarship focused on mountain areas with specific regard to the Global North.

The Dolomites context offers an opportunity to explore contested mountain environmental futures and their politicization under conditions of the eco-climate crisis. By adopting a political ecology approach, this research seeks to make a critical contribution to mountain geography debates. It does so first by questioning the depoliticized perspective on governance mechanisms, sustainable development and community involvement supported by Messerli and Rey (2012), Balsiger and Debarbieux (2015), and Sarmiento (2020), among others; indeed, this article points out the power asymmetries in decision-making processes and widespread exclusion of communities, as well as the way sustainable development discourses deployed to pursue specific political interests. Moreover, by employing a political ecology perspective, this article has explored commodification-oriented mountain development politics related to infrastructural initiatives with findings that reinforce arguments of Stoddart (2013) about skiing ecopolitics in the controversial production of mountainscapes, as well as emerging environmental struggles and their role in pushing for transformative change in mountain futures.

Second, by focusing on conservation, the research sheds light on Dolomites' conservation visions and politics in dialogue with Büscher and Fletcher's (2020) idea of convivial conservation. Even though institutionally protected Dolomites areas employ diverse approaches, they tend to reproduce a society–environment divide and be based on principles in line with mainstream conservation and neo-protectionist perspectives. Indeed, several different actors have challenged the UNESCO active conservation vision on the grounds that it has proved unable to foster an integrated socio-environmental conservation vision outside of UNESCO protected areas. In contrast, local collective property owners, such as usi civici and regole, stress alternative conservation visions that have not been considered in depth by scholars such as Favero et al. (2016) and Dalla Torre et al. (2022). Indeed, these experiences demonstrate, through their everyday life politics and practices, the controversial flaws of neo-protectionist approaches and their historical role in governing mountain resources through a socio-environmental-integrated perspective that promotes a grassroots community conservation beyond protected areas. The Regole d'Ampezzo in particular emphasized that they take a grassroots participatory democratic approach to conservation. This approach characterizes the governance of both their land and the Dolomiti d'Ampezzo natural park, in contrast to the centralized vision applied to other protected areas. Furthermore, the Regole d'Ampezzo has shown itself capable of furthering sustainable natural resource use by fostering environmental care for future generations in a long-term perspective. For instance, these collective properties have sought to curb further commodification of the mountain by taking an oppositional position in negotiations with the municipality and external private actors.

By reflecting on Dolomites collective property unions in relation to the idea of convivial conservation, therefore, it can be argued that the community-based collective management of natural resources and integrated grassroots conservation in and beyond protected areas combined with a long-term perspective of environmental care in relation to the eco-climate crisis constitute practices and visions that resonate with the principles of convivial conservation. They intersect in particular by looking outside of protected areas as well, rejecting the human–non-human dichotomy and valuing shared democratic engagement in conservation (Büscher and Fletcher 2020). Iordachescu (2022), focusing on the Carpathian Mountains in Romania, has argued that land commons in this area offer valuable lessons regarding the kind of transformative change envisioned by the convivial conservation vision. Despite their activities and practices, the Dolomites collective properties do not seem to have enough potential to become a significant alternative for the environmental future of the Dolomites. This is because the Dolomites-area unions are characterized by heterogenous visions and varying interests that in turn reflect differing amounts of bargaining power and diverse positions in relation to institutions and private actors.

The convivial conservation perspective and a radical, alternative vision of the future can instead be found in Dolomites environmental struggles, however. These movements, which also include representatives of collective property owners, are pushing for transformative change in mountain development politics by stressing limits to growth, accumulation and commodification. They demand greater democratization in governance processes and call for a vision of mountain environmental care that extends beyond sustainability and towards more just mountain environmental futures.

This analysis of the Dolomites' contested environmental futures has thus made it possible to reflect more deeply on the politicization of mountains against the background of the current eco-climate crisis in a way that calls into question the depoliticized perspective prevailing in mountain geography scholarship. The politicization of mountains entails the intersection of diverging and contested visions and ideas, and of multiple actors' politics, interests and practices in the everyday production of mountain socio-environmental relations and futures. Second, by discussing convivial conservation principles in relation to examples of collective property ownership and emerging environmental struggles, the research, following key contributions by Stoddart (2013), Iordachescu (2022), and Voicu and Vasile (2022) among others, strengthens and advances scholarship on the political ecology of the mountain with specific regard to the Global North. This reflection on Global North mountains has the potential to further our understanding of the conflicting future visions of mountains threatened by the effects of the climate crisis, as well as environmental extractivism and commodification processes, and support radical initiatives and claims focused on justice-oriented transformative change in mountain socio-environmental relations.

Qualitative data were collected via ethnographic research. Sections 3, 4 and 5 were designed using data collected during personal communications between the author and various actors and individuals.

The author has declared that there are no competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

I would like to thank Bram Büscher and Robert Fletcher for their support and discussions during my visiting stay at the Sociology of Development and Change Group of the Wageningen University. I would also thank the editor Jevgeniy Bluwstein and the two anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

This paper was edited by Jevgeniy Bluwstein and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Balsiger, J. and Debarbieux, B.: Should mountains (really) matter in science and policy?, Environ. Sci. Policy, 49, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.03.015, 2015.

Benjaminsen, T. A. and Svarstad, H.: Political Ecology: A Critical Engagement with Global Environmental Issues, Springer International Publishing, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-56036-2, 2021.

Bluwstein, J.: From colonial fortresses to neoliberal landscapes in Northern Tanzania: a biopolitical ecology of wildlife conservation, Journal of Political Ecology, 25, 144–168, 2018.

Brockington, D., Duffy, R., and Igoe, J.: Nature unbound: conservation, capitalism and the future of protected areas, Routledge Earthscan, ISBN 9781844074402, 2008.

Bryant, R. L.: The International Handbook of Political Ecology, Edward Elgar Publishing, ISBN 978 1 78643 843 0, 2017.

Büscher, B.: Payments for Ecosystem Services as Neoliberal Conservation: (Reinterpreting) Evidence from the Maloti-Drakensberg, South Africa, Conserv. Soc., 10, 29–41, 2012.

Büscher, B. and Fletcher, R.: Accumulation by Conservation, New Polit. Econ., 20, 273–298, 2015.

Büscher, B. and Fletcher, R.: The Conservation Revolution: Radical ideas for saving nature in the Anthropocene, Verso, ISBN 978-1788737715, 2020.

Casanova, L.: Avere cura della montagna. L'Italia si salva dalla cima, Altreconomia, ISBN 9788865163832, 2020.

Castree, N.: Environmental Issues: Relational Ontologies and Hybrid Politics, Prog. Hum. Geog., 27, 321–334, 2003.

Cavanagh, C. J. and Benjaminsen T. A (Eds.): Special section: political ecologies of the green economy, Journal of Political Ecology, 34, 200–341, 2017.

Dalla Torre, C., Stemberger, S., Bottura, J., Corrent, M., Zanoni, S., Fusari, D., and Gatto, P.: Revitalizing Collective Resources in Mountain Areas Through Community Engagement and Knowledge Cocreation, Mt. Res. Dev., 42, https://doi.org/10.1659/mrd.2022.00013.1, 2022.

Debarbieux, B. and Price, M. F.: Representing Mountains: From Local and National to Global Common Good, Geopolitics, 13, 148–168, 2008.

Dematteis, G.: La metro-montagna di fronte alle sfide globali. Riflessioni a partire dal caso di Torino, Journal of Alpine Research, 106-2, 34–44, 2018.

Favero, M., Gatto, P., Deutsch, N., and Pettenella, D.: Conflict or synergy? Understanding interaction between municipalities and village commons (regole) in polycentric governance of mountain areas in the Veneto Region, Italy, Int. J. Commons, 10, 821, https://doi.org/10.18352/ijc.470, 2016.

Ferrario, V. and Marzo, M.: La montagna che produce, Mimesis, ISBN 9788857573564, 2020.

Fonstad, M. A.: Mountains: A Special Issue, Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr., 107, 235–237, 2017.

Forsyth, T.: Mountain myths revisited: integrating natural and social environmental science, Mt. Res. Dev., 18, 107–116, 1998.

Funnel, D. and Price, M.: Mountain geography: a review, Geogr. J., 169, 183–190, 2003.

IPCC: Climate Change: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844.001, 2022.

Iordachescu, G.: Convivial Conservation Prospects in Europe-From Wilderness Protection to Reclaiming the Commons, Conserv. Soc., 20, 156–166, 2022.

Ives, J. D. and Messerli, B.: Progress in theoretical and applied mountain research 1973–1989, and future needs, Mt. Res. Dev., 10, 101–27, 1990.

Kareiva, P., Marvier, M., and Lalasz, R.: Conservation in the Anthropocene, Breakthrough Magazine, 1–13, 2012.

Kothari, A., Salleh, A., Escobar, A., Demaria, F., and Acosta, A.: Pluriverse: A post-development dictionary, Tulika Books, ISBN 9788193732984, 2019.

Kovács, E. K., Ojha, H., Neupane, K. R., Niven, T., Agarwal, C., Chauhan, D., Dahal, N., Devkota, K., Guleria, V., Joshi, T., Michael, N. K., Pandey, A., Singh, N., Singh, V., Thadani, R., and Vira, B.: A political ecology of water and small-town urbanisation across the lower Himalayas, Geoforum, 107, 88–98, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.10.008, 2019.

Kumar Sharma, S., Manandhar, P., and Khadka, S. R.: Political Ecology of Everest Tourism – Forging Links to Sustainable Mountain Development, VDM Verlag, ISBN 9783639306552, 2010.

Lasen, C.: Biodiversité végétale, valeurs naturelles et sauvegarde du paysage dans le domaine dolomitique, Fl. Medit., 31, 521–544, 2022.

Loftus, A.: Political Ecology I: Where Is Political Ecology?, Prog. Hum. Geog., 43, 172–182, 2017.

Marijnen, E., De Vries, L., and Duffy, R.: Conservation in violent environments: Introduction to a special issue on the political ecology of conservation amidst violent conflict, Polit. Geogr., 87, 102253, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102253, 2021.

Messerli, P. and Rey, L.: Integrating physical and human geography in the context of mountain development: the Bernese approach, Geogr. Helv., 67, 38–42, https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-67-38-2012, 2012.

Mukherji, A., Sinisalo, A., Nüsser, M., Garrard, R., and Eriksson, M.: Contributions of the cryosphere to mountain communities in the Hindu Kush Himalaya: a review, Reg. Environ. Change, 19, 1311–1326, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-019-01484-w, 2019.

Pascolini, M.: Le Alpi che cambiano. Nuovi abitanti, nuove culture, nuovi paesaggi, Forum, ISBN 978-8884204615, 2008.

Perlik, M.: The Spatial and Economic Transformation of Mountain Regions – Landscape as Commodity, Routledge, ISBN 9780367662547, 2019.

Perreault, T., Bridge, G., and McCarthy, J.: The Routledge Handbook of Political Ecology, Routledge Earthscan, ISBN 9780367407605, 2015.

Robbins, P.: Political Ecology: A Critical Introduction, Wiley Blackwell, ISBN 978-0470657324, 2012.

Rudaz, G.: The Cause of Mountains: The Politics of Promoting a Global Agenda, Global Environ. Polit., 11, 44–63, 2011.

Sarmiento, F. O.: Montology manifesto: echoes towards a transdisciplinary science of mountains, J. Mt. Sci., 17, 2512–2527, 2020.

Stoddart, M. C. J.: Making Meaning Out of Mountains: The Political Ecology of Skiing, UBC Press, ISBN 978-0774821971, 2013.

Smith, N.: Uneven Development: Nature, Capital and the Production of Space, Basil Blackwell, ISBN 9780631136859, 1984.

Swyngedouw, E.: Depoliticized Environments: The End of Nature, Climate Change and the Post-Political Condition, Roy. I. Ph. S., 69, 253–274, 2011.

Toncheva, S., Fletcher, R., and Turnhout, E.: Convivial Conservation from the Bottom Up: Human-Bear Cohabitation in the Rodopi Mountains of Bulgaria, Conserv. Soc., 20, 124, https://doi.org/10.4103/cs.cs_208_20, 2022.

Varotto, M.: Montagne di mezzo – Una nuova geografia, Einaudi, ISBN 9788806230418, 2020.

Vasile, M.: Forest and pasture common in Romania. Territories of life, Potential ICCAs: Country report, ICCA Consortium, 1–53, 2019.

Vasile, M. and Iordachescu, G.: Forest crisis narratives: Illegal logging, datafication and the conservation frontier in the Romanian Carpathian Mountains, Polit. Geogr., 96, 1–12, 2022.

Voicu, S. and Vasile, M.: Grabbing the commons: Forest rights, capital and legal struggle in the Carpathian Mountains, Polit. Geogr., 98, 1–11, 2022.

Wilson, E. O.: Half-earth: our planet's fight for life, Liferight Publishing, ISBN 9781631490835, 2016.

Zinzani, A. and Curzi, E.: Urban regeneration, forests and socio-environmental conflicts: the case of Prati di Caprara in Bologna (Italy), ACME, 19, 163–186, 2020.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Mountain futures: linking the political ecology of conservation to mountain geographies

- Governance, conservation and environmental struggles in the Dolomites

- The Dolomites' contested environmental futures

- Contested futures and convivial conservation: advancing the political ecology of the mountain in the Global North

- Data availability

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Mountain futures: linking the political ecology of conservation to mountain geographies

- Governance, conservation and environmental struggles in the Dolomites

- The Dolomites' contested environmental futures

- Contested futures and convivial conservation: advancing the political ecology of the mountain in the Global North

- Data availability

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References