the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Infrastructures in the context of arrival – multidimensional patterns of resource access in an established and a new immigrant neighborhood in Germany

Leoni Keskinkılıc

Recent debates on arrival cities, neighborhoods, or other scales of local contexts tend to focus on aspects of local areas which support new migrants in accessing resources such as social networks, organizations, and other kinds of local infrastructure that give access to (multilingual) information, housing options, first jobs, or a sense of belonging and conviviality. These features are often concentrated in long-standing immigrant neighborhoods. In this contribution, we compare different kinds of local infrastructure in two German local contexts – in an established immigrant neighborhood and a rather new immigrant neighborhood – and how they have shaped the arrival of refugees who have come to Germany since 2014/15. We emphasize the need to understand infrastructures and the way they shape arrival, first, in a multidimensional way that, second, comprises inclusive as well as exclusive aspects of local infrastructures. This, third, includes the need to specify for which category of people infrastructures work in an inclusive or exclusive way as they work differently along a range of social boundaries.

- Article

(394 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

In the following article we analyze infrastructures in two different neighborhoods that refugees encounter upon their arrival and look at how these infrastructures shape their processes of arrival by either giving or denying them access to resources. By doing so we build on debates on arrival contexts as well as on debates around infrastructure. We find the current debate on arrival contexts – terms used in this debate include arrival cities, neighborhoods, spaces, or areas (Franz and Hanhörster, 2020; Gerten et al., 2022; Hanhörster and Wessendorf, 2020; Saunders, 2011) – helpful for investigating which kinds of local conditions and resources shape the arrival of migrants. In the following, however, we refrain from using “arrival” as an adjective describing cities, infrastructures, or neighborhoods but instead look at the relevance of different kinds of local infrastructures in the context of the arrival processes. Similarly to Meeus et al. (2019, 2020), we argue it is crucial to connect the debate on arrival to literature on infrastructure in order to examine which features of a specific place make resources accessible or inaccessible and for whom.

We do not, however, speak of “arrival infrastructures” as we would like to emphasize that, first, the infrastructures connected to a place shape arrival for the better or worse and that – in addition to the inclusive aspects – we need to include excluding aspects of the arrival process more explicitly in the debate. By refraining from using arrival as an adjective, we therefore emphasize that arrival is not equal to support and inclusion but can also be shaped by exclusion. This is inter alia important in order to understand how very different places shape arrival processes. The debate so far has tended to focus on “typical” immigrant neighborhoods whose support functions are rather well known, while “non-typical” or more exclusionary places have received less attention until recently (El-Kayed et al., 2020). Second, we show that the same location can offer access to supportive structures as well as to exclusionary ones and that more often than not people who arrive somewhere may experience both at the same time. We therefore need to develop a multidimensional understanding of infrastructures that shape arrival processes. Third, the same infrastructure can work in an inclusionary way for one category of people and in a non-functional or exclusionary way for others.

In the following we illustrate these arguments by examining infrastructures that shape arrival processes in two contexts which vary strongly in their previous migration history: one neighborhood, Berlin-Kreuzberg, can be described as a typical and long-standing immigrant neighborhood, while in the other, Dresden-Gorbitz, migrant residents and support structures were not equally prevalent a few years ago. In both places, we look at three different kinds of infrastructures – housing, public space, and social infrastructure such as social work and counseling services – and examine how they shape the arrival processes of refugees who came to Germany since 2014/15 when the number of refugees rose sharply due to international crises, ongoing conflicts, and war. In 2015 and 2016 about 1 million asylum applications were registered by the German Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) (BMI, 2016). After that, the number of people seeking refuge dropped – not least due to restrictive European asylum policies (Hess and Kasparek, 2019) – and are currently rising again, mostly due to the war in Ukraine. In 2015 and the following years, huge deficiencies on many levels of politics and administration were exposed. In many German cities and municipalities, public administrations did not organize adequate care and accommodation for the newly arrived refugees. Often, civil society actors tried to bridge existing gaps by providing food, shelter, legal advice, and other forms of support (Hamann et al., 2016). Local conditions of arrival can differ strongly due to the prevalence of civic organizations, economic conditions including job and housing markets, or previous local migration histories which amongst other aspects shape the existence of migrant networks or multilingual services. How such local variances affect the arrival process of refugees is a question we posed in a larger research project that has generated the material presented here (El-Kayed et al., 2021).1

Before we outline our findings on how local infrastructures shape arrival processes of relatively recent refugees, we will, first, discuss the literature on arrival areas and infrastructure in more detail and, second, introduce the methodology of the study. We conclude with a discussion of our findings.

2.1 Arriving locally: old and new debates

The way in which residential segregation influences immigrants' social mobility and integration has been debated for a long time (Breton, 1964; Burgess, 1928; Wilson, 1987). A crucial question in this debate asks whether the spatial concentration of immigrant households isolates them from other parts of society and therefore delays processes of social integration and mobility, such as learning the dominant language of the country of residence (Esser, 1986; Florax et al., 2005; Wilson, 1987), or whether immigrant neighborhoods provide crucial local infrastructures such as immigrant organizations and social networks which give access to information, social contacts, jobs, a sense of familiarity, and other resources that increase social mobility (Marten et al., 2019; Musterd et al., 2008; Nieuwenhuis et al., 2017; Portes and Bach, 1985; Zhou, 2009). Marten et al. (2019) demonstrate, for example, that refugees who are assigned to areas where they live with a large number of other residents with whom they share their nationality, ethnicity, or language show a higher likelihood of accessing the local labor market.

The latter argument has been taken up in the debate on arrival cities or contexts in recent years. The 2011 book Arrival City by journalist Doug Saunders drew renewed attention to urban areas where transnational and intranational migrants reside, areas that work, he argues, as stepping stones towards middle-class lives, framing these urban areas not as places of decay, segregation, and social immobility but as places of potential and transition (Saunders, 2011). A connected academic discussion has emerged around the question of which localities offer favorable conditions for the arrival and subsequent social mobility of immigrants – under terms like arrival cities, neighborhoods, contexts, areas, spaces, or infrastructures (see, e.g., Franz and Hanhörster, 2020; Meeus et al., 2019; Schillebeeckx et al., 2019). Despite using different terms, these contributions seek to highlight local conditions that enable migrants to access information and other resources, to build social networks, and to realize social mobility. Besides focusing on such inclusive spatial conditions, this debate is distinct from research on immigrant integration in that it focuses on arrival and thus on the early phase of a potentially long-term settlement process.

Most contributions to the debate focus on local characteristics which are supportive and have a positive influence on arrival processes. Typical arrival areas are often characterized as offering accessible and/or cheap housing, being already significantly shaped by migration, and therefore as offering newly arrived immigrants easier access to networks, information, jobs, or housing. These are also often areas which are depicted as dense in terms of residential population, buildings, and organizational or social infrastructure (El-Kayed et al., 2020; Franz and Hanhörster, 2020). However, the literature on how arrival works in other contexts such as peripheral and rural contexts and/or areas which are less shaped by prior migration and migrant networks is expanding (De Vidovich and Bovo, 2021; Dunkl et al., 2019; Flamant et al., 2020; Gerten et al., 2022; Steigemann, 2019). This work provides, for example, insights into everyday mobility strategies of refugees in rural areas that they employ in order to access education or work or to visit friends and family, as well as insights into constellations of reception in rural areas (Mehl et al., 2023).

The cited debates on segregation and arrival mainly focus on immigrant populations with limited economic resources – although migration is of course a broader phenomenon that also includes high-skilled and legally more privileged migration. In the following we focus on refugees who have arrived in Germany since 2014/15 and have applied for asylum. Persons falling into this category are not a homogenous group and have, for example, different educational levels (Brücker et al., 2020). However, seeking asylum in Germany means entering a legal process that governs spatial and social mobility conditions in specific ways and therefore shapes refugees' needs for counseling as well as access to housing or job markets (El-Kayed and Hamann, 2018).

2.2 Arrival and infrastructures: considering inclusive and exclusive aspects

Rather than focusing on whole arrival areas, Meeus et al. (2019) propose to look at specific infrastructures and define arrival infrastructures as those “parts of the urban fabric within which newcomers become entangled upon arrival, and where their future local or translocal social mobilities are produced as much as negotiated” and where they “find the stability to move on” (Meeus et al., 2019:1; see also Meeus et al., 2020). Analyzing arrival through such an infrastructural lens is helpful as it focuses on the features that anchor and support arrival in specific places. It is a way to analyze if, how, and which characteristics of local contexts matter and therefore a way to examine the underlying social mechanism more closely. It furthermore does not label a whole context or area as supportive of arrival. This opens up a wider range of options to analyze arrival processes including the opportunity to understand such infrastructures as being fractured, translocal, or located in non-residential or “atypical” areas (Zhou, 2009; El-Kayed et al., 2020).

Yet the notion of arrival infrastructures as well as that of arrival areas, spaces, or neighborhoods focuses more on inclusive, supportive, and social-mobility-enhancing features of localities. The usage of arrival as an adjective implies a primarily positive connotation. Saunders argues, for example, that “the properly functioning arrival city provides a social-mobility path into either the middle class or the sustainable, permanently employed and propertied ranks of the upper working class” (Saunders, 2011:20). Thus, there is a danger of overlooking, first, exclusive features of typical arrival areas or infrastructures (Haase et al., 2020; Felder et al., 2020:62) and, second, different patterns of how local contexts shape arrival processes. The same area can, for example, host very effective job information networks and at the same time an educational infrastructure which is dysfunctional for social upward mobility. Both are relevant infrastructures which shape the arrival process while offering very different (in)accessibility to crucial resources. Furthermore, not all arrival infrastructures are similarly inclusive or helpful to everyone. Their inclusivity or exclusivity can depend, for instance, on categorizations and classifications based on gender, age, country of origin, language skills, or racism. Felder et al. (2020), for example, highlight the often “ambiguous role” of arrival infrastructures, their barriers, and the often limited and conditional resources therein (cf. Felder et al., 2020:62). Different modes and constellations of local resource accessibility and resource provision also enter the debate when different types of arrival areas are included in the discussion (Gerten et al., 2022). Thus, in order to avoid an a priori positive connotation of arrival, we do not use the term arrival as an adjective for areas, contexts, or infrastructures here and instead examine the question of how locally embedded infrastructures shape the process of arriving. This enables an analysis of the positive and negative, as well as ambiguous, effects of local infrastructures.

Here, we propose to understand arrival as a phase in the migration process in which newly arrived migrants first encounter a new context – without including outcomes of this process (such as social mobility or resource access) in the definition. Whether, and what kind of, resource accessibility or social mobility may be part of an arrival process can then become an open question (or a dependent variable). Arrival in this sense is of course not a clearly defined time frame but rather a fuzzy one. Nonetheless, it differentiates the debate from long-standing discussions on immigrant integration, which often focus on longer-term or multi-generational time spans. The notion of arrival has, furthermore, the advantage of being separated from negative connotations of integration concepts in public and academic debates. While concepts of immigrant integration can also focus on resource access and social inequality within immigrant societies, many include aspects of cultural adjustment or assimilation, which has provoked important critiques in the past (Hess et al., 2009; Röder, 2019). The word integration, furthermore, invokes the image of a “whole” into which outsiders need to be integrated and therefore – implicitly or explicitly – tends to homogenize the non-migrant part of society.

In sum, focusing on the arrival phase means examining processes of initial orientation and situatedness such as navigating bureaucratic systems, finding housing, or finding a first job. We do not think that it is useful to try to limit this phase to a set time frame of a specific period but instead include people in our research who are still in a phase of situating and orienting themselves. Especially for asylum seekers who depend on legal processes, which often take years to complete, arrival can take a long time, and problems with accessing resources like housing can furthermore prolong this period.

But what exactly are infrastructures and why is it useful to study them? From the perspective of anthropology, sociology, and social geography, the term infrastructure refers to the socio-material underpinnings of social processes (Amin, 2014; Larkin, 2013; Müller et al., 2017). Larkin (2013) for example, emphasizes the following:

Infrastructures are built networks that facilitate the flow of goods, people, or ideas and allow for their exchange over space. As physical form they shape the nature of a network, the speed and direction of its movement, its temporalities, and its vulnerabilities to breakdown … Their peculiar ontology lies in the facts that they are things and also the relation between things. (Larkin, 2013:328–329)

Looking at infrastructures in this way therefore includes examining how an infrastructure's material and social features shape access to various resources and services for specific social groups in specific places. This renders the concept of infrastructure helpful to analyze local conditions of resource access during arrival processes.

The analysis of infrastructure encompasses various fields. Studies on technological infrastructures such as roads, bridges, water pipes, or digital systems analyze questions of power, politics, and social inequality via access to goods and resources that are circulated by or through these technological infrastructure networks – including the analysis of social norms, rules, and networks that are essential to their operation (Amin, 2014; Angelo and Hentschel, 2015; McFarlane and Rutherford, 2008; Star, 1999). The term “social infrastructure” refers to institutions and organizations which distribute and provide specific resources. Barlösius et al. (2011) look at schools as an example for social infrastructure which provides a specific kind of communication and interaction (p. 154). Similarly, Klinenberg (2018) understands a wide array of institutions, organizations, and facilities as social infrastructures – from libraries, schools, and civic associations to parks, markets, and sidewalks (p. 16). These all have in common the fact that they offer possibilities “to socialize and connect with others” and are to some degree public (Latham and Leyton, 2019). Emphasizing social connections, Simone (2004) refers to “people as infrastructure”, as “a conjunction of heterogeneous activities, modes of production, and institutional forms” that constitute “highly mobile and provisional possibilities for how people live and make things, how they use the urban environment and collaborate with one another” (Simone, 2004:410).

These studies provide a number of insights which are also useful for the study of arrival. First, they steer the analysis to the spatial interwovenness of material and social aspects of accessing resources that then shape social inequality. This allows for asking questions about the ways in which access to resources is provided by and to specific places and how it conversely shapes these places. Thus, the analysis of infrastructure provides, second, a socio-material view on state power or questions of distributive justice and invokes questions such as for whom and where does the state and other agents provide which kind of (non-)reliable access to resources via which kind of infrastructural networks. Third, connected to this, the literature on infrastructure sheds light on the fact that infrastructure needs to be studied relationally and that it can mean different things to different people, or in the words of Star (1999), “One person's infrastructure is another's topic, or difficulty” (Star, 1999:380). Mohkles and Sunikka-Blank (2022), for example, show how women in an informal settlement in Iran use different spaces than men to socialize, feel safe, and be physically active. In this article we show that this is an especially useful insight for the study of arrival, as an infrastructure can provide one arriving person with helpful resources and can be insignificant or hurtful to the arrival process of another. This sheds light on the importance of studying social boundaries (Lamont and Molnár, 2002; Tilly, 2004) in the context of infrastructure and how they work across and along such boundaries (see Lipsky, 1980, in regard to social infrastructures such as schools or welfare offices). It furthermore emphasizes the importance of focusing on the context in which refugees arrive and therefore connects well with approaches that examine different “opportunity structures” or degrees of receptivity that refugees encounter in regard to policy, social relations, or civic society structures (Glorius et al., 2021; Phillimore, 2021).

In the following we look at three different kinds of infrastructures which are central to gaining orientation in a new local context: housing, social infrastructures, and public space. Access to housing is a core part of arriving in a specific local context (cf. Gardesse and Lelévrier, 2020:138). Asylum seekers in Germany are allocated to a specific locality where they usually have to live in collective accommodation first. Even when they have completed the asylum process and are able to look for private housing, they remain obliged to live in the federal state (Bundesland) where they underwent the process for another 3 years (exceptions apply as well as more restrictive regulations in some regions; El-Kayed and Hamann, 2018). The initial allocation to a region therefore often establishes a strong path dependency. Respective government regulations and housing markets, as well as personal networks and preferences, influence where refugees find access to private housing. The way public space is experienced is related to topics of personal security, encountering others, and feelings of (un)familiarity (Low and Smith, 2006; Blokland and Nast, 2014). Finally, we look at social infrastructures which we – following the literature cited above – understand as organizations and institutions that provide a specific form of communication and interaction (Barlösius et al., 2011; Klinenberg, 2018). This includes, e.g., social work, social services, or educational facilities such as kindergartens and schools. These structures and the way they work are often crucial in order to gain access to relevant information, orientation, and support.

In our analysis we focus on the scale of the neighborhood because we are interested in whether and how specific places provide (or do not provide) specific resources and for whom. However, we do not assume that these places are necessarily the most crucial or the only places where refugees and other new immigrants obtain access to resources that then structure their future social mobility. Furthermore, places do not provide resources exclusively for their residents and are also co-produced by structures and regulations on other scales – e.g., via citywide or national regulations and dynamics. Still, the kinds of infrastructures provided in the immediate residential environment influence to what extent people need to look for resources elsewhere. Whether they can do so is then also dependent on the availability of resources on the city or regional scale as well as on the availability of mobility or communication infrastructures (Berg, 2022; Mehl et al., 2023). Focusing on the neighborhood scale is therefore a relevant starting place for analysis.

We explore these questions on the basis of material from the research project “Welcoming Neighborhoods”, which examined from 2017 to 2021 the questions of in which kinds of local contexts refugees gain access to key resources such as housing, support, and participation and how their access to these resources is locally negotiated and lived. In the project, we compared four neighborhoods whose socio-economic composition and previous migration histories varied systematically as we were interested in the ways in which these two factors influenced the reception of refugees on different levels. Two neighborhoods in our comparison had a rather low socio-economic profile but varied in their migration experience – one of them, Berlin-Kreuzberg, had extensive previous migration experience, whereas the other, Dresden-Gorbitz, had not. The second set of neighborhoods also differed in their previous experience with migration while their socio-economic status was higher (Stuttgart-Untertürkheim and Hamburg-Eppendorf). In the following we focus on the first set of neighborhoods with a rather low socio-economic status as they can be seen as representing a long-standing context of arrival on the one hand and a newly developing context of arrival on the other hand.

In each of the neighborhoods, we conducted qualitative interviews with refugees who came to Germany since 2014/15 and live in or use the selected neighborhoods. The refugees we talked to either were allocated to the neighborhoods through administrative processes or had been able to find private housing there – the extent to which either was accessible varies substantially across the examined neighborhoods, as we will see below. In these interviews we were interested in the participants' experiences in the neighborhoods and whether and how they accessed various resources such as housing or social support in them. Qualitative interviews with local key actors from the fields of social work, civil society, city politics, or administration were also part of the research project as well as a standardized survey that was conducted among the established resident population and included inter alia questions on attitudes towards refugees or civil society support for refugees. In the following, we are interested in how refugees encounter local infrastructures upon arrival in a typical, established immigrant neighborhood as opposed to a context where migration is not a well-established phenomenon. Therefore, we mainly use material from our interviews with refugees. However, the analysis below is also informed by other parts of the research (El-Kayed et al., 2021).

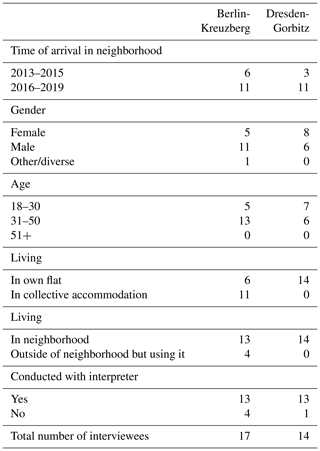

In Berlin-Kreuzberg we interviewed 17 and in Dresden-Gorbitz 14 refugees aged 18 or older (all interviews were conducted in 2019). The interviewees arrived in Germany between 2013 and 2019, and their period of use of or residence in the neighborhoods varied from a few weeks to a few years. In all of the interviews, major topics were finding housing, jobs or education, and securing a residence status – either currently or retrospectively – which is why we consider all interviews relevant to explore conditions of arrival. The length of the interviews varied from 30 to 90 min and were mostly conducted with interpreters who translated the interviews into German or English (see Table 1). The role of interpreters has different effects that require reflection both in the interview situation itself and while analyzing the interview material: first, interpreters reduce language barriers and enable participation in interviews in the preferred language. At the same time, however, the interpreters' translation is an interpretative social practice and not merely a reproduction of what is said in another language – even if everything is translated “correctly”. Interpreters, secondly, add an additional perspective: they bring in subjective notions as they have a mediating role between different representational systems – often in a third-person narrative (cf. among others Husseini de Araújo and Kersting, 2012; Mattissek et al., 2013). Both aspects were taken into account in the following analyses. In the following, we indicate when an interview was conducted with an interpreter in the introduction to quotations (e.g., “The interpreter translates”). In these cases, the interviewees' accounts are given in the third person through the voice of the interpreter.

The two neighborhoods from our case study represent very different local constellations of infrastructures that shape arrival processes. The aim here is to discuss which access to resources these spaces provide and, in doing so, to take a differentiated look at three different kinds of infrastructures in these contexts: (1) housing, (2) public space, and (3) social infrastructure with a focus on social services. These infrastructures are often intertwined in the ways they work. This is for example the case when counseling services help refugees to find housing or when public space is co-constituted by the presence of civic organizations and their events. Furthermore, they are co-created by other infrastructures. In the case of refugees, state administrations on several scales enforce and regulate welfare criteria and asylum procedures which are especially important for the question of how and where refugees can find housing.

The aim of the following comparison is not to explain how the different infrastructure constellations in the two neighborhoods came about but to explore how these constellations shape the arrival or refugees and give (or do not give) them access to crucial resources such as housing or social support in a multidimensional approach.

4.1 Berlin-Kreuzberg

In Berlin, the study area is a part of the inner-city district Kreuzberg and includes areas with a high density and mix of commercial or cultural facilities and residential houses, as well as purely residential streets. The area is characterized by a long history of migration as well as experiences of social deprivation and has a well-established infrastructure of social work, counseling services, and civic initiatives which have extensive experiences of working with people of diverse backgrounds. The district has been shaped by migration since the 1960s when work migration to post-war West Germany started. Then it received mainly immigrants from Türkiye (anglicized Turkey) and is now home to a wide range of immigrant groups. Kreuzberg as a whole is well known for its diverse population, active leftist scene, and numerous art and cultural venues. The area we studied lies at the periphery of the district and includes fewer of the pre-war buildings that other parts of the district are famous for and has a higher number of purely residential blocks built in the post-war era. However, there is still a considerable mix of commercial, civic, and cultural facilities in the area as well as close by. In 2018, the share of the population without German citizenship in our study area was 35.9 % (Berlin: 20.0 %) and the share of people registered as unemployed was 9.4 % (Berlin: 4.2 %). Since 2014/15, refugees have been accommodated in the neighborhood primarily in two collective accommodations to which they were assigned. The housing market in the neighborhood has been increasingly tight and strongly characterized by rising rents and gentrification for a number of years. Due to these reasons, only a limited number of refugees have been able to find private apartments in the neighborhood (El-Kayed et al., 2021). Here, we interviewed both refugees who live in the neighborhood and refugees who use infrastructure in the neighborhood but do not reside there.

4.1.1 Housing: high barriers to find private housing

In the interviews, refugees living in Kreuzberg often mention that the neighborhood has become the center of their life. However, most of the refugees we spoke to have not been able to find private housing there and still live in collective accommodation. They consider their chances of finding an apartment in the neighborhood to be very low due to various barriers. As mentioned above, rents in the study area have been rising rapidly in recent years. In addition, refugees often lack information, orientation, and support when looking for apartments. This gets further complicated by language barriers, bureaucratic and other requirements for applications (e.g., filling out forms for public authorities), and discriminatory attitudes by landlords. Local initiatives often find it difficult to provide the necessary support during the search for housing due to limited funds and personnel. Because of such barriers, most residents we spoke to have been living in shared state accommodation for several years although they are legally allowed to move out of it. Some interviewees have concerns about having to move to less immigrant and less central neighborhoods of Berlin, where they expect a higher level of racist hostility. One interviewee described her experiences in such neighborhoods in an interview which we conducted with an interpreter, who translated her account as follows:

When she lived there in [a less central, less immigrant neighborhood] … she didn't feel comfortable. For example, when she went shopping at the supermarket, everyone looked at her strangely, so she didn't feel welcome at all. Although she now hears that there are now many Arabs, but she doesn't want to move there again. (Interview 3-4)

Overall, the housing market in Kreuzberg remains predominantly closed for newly arrived refugees. Due to numerous barriers and a lack of support services, many refugees we interviewed have been living in a shelter for years. However, living there is not the only aspect that ties people to Kreuzberg. Many interviewees we talked to come to Kreuzberg – even though some of them live quite far away – to use the diverse social infrastructures (e.g., counseling services, language courses), to meet and connect to people, or to feel comfortable in the experienced everydayness of diversity in Kreuzberg (see below).

4.1.2 Public space: blending in for some, racist discrimination for others

When we asked refugees how they would describe the neighborhood in Kreuzberg, most said that they experience Kreuzberg as a super-diverse neighborhood that is characterized by openness and accessibility. Almost all interviewees referred positively to the public visibility of previous migration history and the presence of different socio-economic groups and political initiatives in the neighborhood. Often connected to the visible diversity in public space, the experience of feeling safe and comfortable in the neighborhood dominates among the interviewed refugees. This includes in particular the experience of hardly being noticed and being able to “blend in” on the street. This is especially the case for refugees from Middle Eastern countries. One interviewee describes the feeling of being “almost equal” as well as the feeling of “no insecurity” in public space, especially “looking at the fact that there are many, many Arabs here” (Interview 3-4).

In addition, most interview partners highlight the many opportunities in the neighborhood to meet and socialize. One points to the mix and density of stores and gastronomic offerings and states,

You don't have to walk around for a long time to find everything, even restaurants or something. (Interview 3-16)

Another interviewee highlights the multiple language resources that open up lots of conversational opportunities for him, as becomes clear in the translation of his account by an interpreter:

He usually sits in a café at [central place] and has met many nice people there. He talks to them in French or Arabic … And that's why he likes the whole atmosphere very much. (Interview 3-12)

Linked to situations like this, many interviewees move in a kind of “comfort zone”, in which they tend to expect and experience inclusive attitudes and develop a kind of public familiarity with the area (Blokland and Nast, 2014).

However, despite this experienced everydayness of diversity (Wessendorf, 2016; Wise and Velayutham, 2009), discrimination also takes place, even if such situations are described less frequently in comparison with the other neighborhoods in the study. Especially Black refugees report racist discrimination in Kreuzberg at a much higher level than other interviewees – for example in cafés, by neighbors in their apartment building, or in public space. One of the main issues during their everyday life is racist profiling by the police. One interviewee expresses that this results in a permanent danger of criminalization and a specific “vulnerability of African refugees” and concludes, “I am not safe here when the police is always there” (Interview 3-16). In concordance with these accounts, we understand public space in the following as an infrastructure which has inclusive and exclusive aspects. It is often regulated (Low and Smith, 2006) and can shape feelings of familiarity and security and can give access to information as well as to fleeting contacts and communications (Blokland and Nast, 2014). On the other hand, public spaces and the social interactions within them can also be experienced as insecure, discriminatory, and threatening.

Thus, despite being often described as a very inclusive place, Kreuzberg is not a neighborhood free of discrimination but one whose public and semi-public spaces like cafés or restaurants are characterized by differentiated and situated processes of inclusion and exclusion. While many refugees – especially from the Middle East – feel safe and “at home” in most situations, others – especially Black refugees – encounter a higher number of discriminatory and dangerous interactions. The infrastructure of public space(s) co-created by people (Simone, 2004) and institutions (here especially the police) in this established immigrant neighborhood results therefore in varying experiences of access, comfortability, (un)easiness, or danger – structured along different kinds of racialized social boundaries.

4.1.3 Social infrastructure: inclusive services and support gaps

Looking at social infrastructure, the neighborhood in Kreuzberg is characterized by a dense network of social work and civil society actors that provide services for refugees and others with migration histories. Some institutions and associations emerged in the course of earlier migratory movements and have long-standing experiences in providing counseling and support in the context of migration, discrimination, and racism (El-Kayed et al., 2021).

In our interviews, refugees mention different existing counseling and support services in the neighborhood which are helpful in various respects. Especially the widespread multilingualism in local institutions and initiatives is often mentioned as a distinct feature of the local social infrastructure. One refugee described his experience with a local association that provides support for various concerns, and the interpreter translated his account during the interview:

[There is a kind of association that is helping immigrants] and he went there … There was a translator for everybody, like every language, like Arabic and Farsi, and they were working for free for them, and he was taking all the letters he was receiving there. (Interview 3-7)

Other helpful services which were mentioned by refugees include, inter alia, volunteer-organized language courses, which according to several interviewees who do not live in the area are a central reason why they come to Kreuzberg every day. Such services turn Kreuzberg into a center of such social infrastructures which are helpful for recent immigrants. Here, we can see that not only a certain area's social infrastructure but also its public space can be important for a wider range of users, beyond its immediate residents (El-Kayed, 2018; Hanhörster and Weck, 2016).

Supportive social infrastructures are, again, not accessible to all refugees in the same way. Particularly, Black refugees from African countries told us that they hardly find any institutionalized support structures. One interviewee shared the impression that they are often not considered a main target group in the local counseling centers, for example in the area of asylum law. He could find only one local initiative that explicitly provides counseling for refugees from African countries.

Thus, on the one hand counseling and support structures in Kreuzberg are well established, quite dense, and inclusive as they cover many languages and needs. They enable access to information, medical care, and legal advice for refugees. On the other hand, this infrastructure is not accessible to all refugees in the same way. Rather, access to and functions of these social infrastructures often only cater to certain groups in terms of countries of origin, languages, or the legal frame under which people migrate.

4.1.4 Kreuzberg – summary

In sum the researched area of Kreuzberg is a highly diverse neighborhood where experiences of migration, poverty, and gentrification are present. On the one hand Kreuzberg can be described as inclusive in regard to its social infrastructure and public as well as semi-public spaces. On the other hand, housing options are highly limited. Looking at these different dimensions, we can see that this neighborhood hosts supportive as well as exclusive infrastructures at the same time and that we therefore need a multidimensional understanding of infrastructures in order to see what exactly offers resource access to whom in which places. This example also shows that the present infrastructures do not offer access to resources for all refugees. While the dense social infrastructures cover diverse language resources and needs, Black refugees from African countries experience considerable gaps in the landscape of services. Many interviewees also emphasize that they mostly feel familiar and comfortable in public and semi-public spaces – especially compared to other neighborhoods in our sample. However, not all situations are free from discrimination and racism, and this is, again, particularly the case for Black refugees, who often encounter racist hostilities as well as racial profiling by the police. There is a need to consider such racialized and other social boundary processes when looking at infrastructures in the context of arrival and to ask which kind of infrastructures support resource access and social mobility for whom.

4.2 Dresden-Gorbitz

Gorbitz is a high-rise, mostly residential area in Dresden. The neighborhood consists of a large housing estate; it has only a few commercial structures and had a relatively low level of migration experiences among its residents prior to 2014/15. The resident population experiences high rates of social deprivation and poverty. In 2018, the unemployment rate in Gorbitz was 13 % (Dresden: 4.8 %). The housing estate was built in the 1980s during the German Democratic Republic (GDR) era and was considered a socially mixed and popular residential area back then due to its modern apartments. Since then, the neighborhood has gone through various changes including the downsizing of local infrastructure, population loss, and collective experiences of marginalization after the end of the GDR. In the 1990s, almost a third of residents moved out of the neighborhood, a time during which the neighborhood was also home to an active right-wing scene according to many local actors. It was not until 2011 that population numbers started rising again (El-Kayed et al., 2021; Landeshauptstadt Dresden Kommunale Statistikstelle, 2020).

Migration in the GDR was mainly shaped by so-called contract workers' migration from Vietnam, Mozambique, Angola, or Cuba, and these migrants often had to leave after German reunification in 1990. During the 1990s migration to East German cities was mainly shaped by migrants from post-Soviet states (Weiss, 2018). Compared to many West German cities and regions, the share of immigrants remained, however, rather low. Since 2014/15 the number of refugee residents rose in many East German cities, especially in peripheral high-rise estates (Helbig and Jähnen, 2019). This is mostly due to a combination of housing market structures and legal regulations that limit the residential movement of refugees to the region where they went through the asylum application for 3 years after they acquire a residence permit (El-Kayed and Hamann, 2018). This in combination with housing market structures and social welfare regulations sorted refugees into this type of neighborhood, which offers an available and affordable housing stock that is often owned by large private real-estate companies that build their financial model on tenants who receive social welfare (Forschungsverbund StadtumMig 2023).

In the case of Dresden, the city accommodated a significant number of refugees in shared apartments in Gorbitz, and many refugees were able to find private housing in the neighborhood when the city's obligation to accommodate them ended. This contributed significantly to the increase in residents without German citizenship in Gorbitz from 7.1 % in 2014 to 15.9 % in 2018. Gorbitz has many institutions that offer social work and counseling services; however, many of them had only limited experiences of working with clients with an immigrant background before 2014/15 (El-Kayed et al., 2021).

4.2.1 Housing: accessibility and no other choice

All refugees we interviewed live in an apartment in the neighborhood. Unlike in Kreuzberg, refugees often moved to Gorbitz because of easy access to apartments due to available housing and affordable rents – not because they were very fond of the area. One person's account was translated by an interpreter like this:

Before he moved here, he had a friend who lived here in another building … Back then, he could never have imagined that he would end up living here, too, because he didn't really want to live here … But he lives here now anyway because the rent is still affordable. It's cheaper than living in the [inner city]. So moving would not be an option for him now. (Interview 3-49)

Another interviewee explains that the only apartment she could find that suited the welfare office's criteria was in Gorbitz. Others were already housed in Gorbitz by the city during their asylum procedure and found an apartment here afterwards. In other cases, refugees wanted to move from rural areas to a larger city, and social contacts connected them to Gorbitz. Still refugees encountered barriers such as lack of information or language accessibility when looking for apartments. Support was mainly provided by personal contacts.

Most of the interviewees moved into their first apartment in Gorbitz after having stayed in shared accommodation. Thus, moving into the neighborhood initially meant a huge gain in autonomy and independence for them. One person describes the following, translated by an interpreter in the third person:

She was actually so happy when she moved here because she could finally be reunited with her family. She could cook, organize her own daily life, wear her clothes like this. (Interview 3-48)

Still, many refugee residents we talked to said that they wanted to move away from Gorbitz or Dresden in the long term. The reasons they mentioned were mainly the lacking variety of infrastructure (shops, restaurants, organizations, etc.) and daily experienced racist hostility. But mainly because of their financial situation, most of the refugees hardly saw a chance to move. That said, a few interviewees also emphasized that they wanted to stay in the neighborhood because their children have their kindergarten, school, and friends there or because of local organizations that offer support.

4.2.2 Public space: visibility and hostility

With regard to perceptions and experiences in public space, there is a tension in the interviewees' narrations between experiencing Gorbitz, on the one hand, as a quiet residential area with an increasing presence of migrant residents and, on the other hand, as a place where they feel exposed and threatened in public space. Families in particular describe the neighborhood as very child-friendly due to the proximity of playgrounds, parks, schools, or kindergartens as well as due to little traffic in the neighborhood. One mother describes,

Gorbitz is very nice because it is quiet and also a bit more closed, also because of the public transport. The children are safe here and can play in the street … We have more space here [than in the city center]. (Interview 3-52)

At the same time, the refugees notice that the neighborhood is less characterized by other immigrants than, for example, the inner city. Almost all of the interviewees mention that they feel very visible in the neighborhood and are hardly able to “blend in” on the street.

Almost everyone we interviewed reported experiencing rejection and hostility on an almost daily basis. Such experiences take place, for example, on the street, at bus stops, or in the apartment building and range from aggressive complaints, racist insults, and damage to property to physical assaults – the latter being reported in particular by women wearing headscarves and by Black residents.

Another central issue is complaints by neighbors in the apartment building due to (alleged) (children's) noise, food smells, and uncleanliness. In the context of such conflicts, racist comments are often made and some neighbors engage in outright threats: a Muslim woman reports that neighbors poured leftover pork and dog excrement on her doormat; another person told us that he was regularly insulted on his way home by an elderly neighbor and that dog owners let dogs run close behind their children. Racist profiling by the police is also an issue in Gorbitz. A Black refugee is regularly stopped by the police in a square near his apartment: “the police check me quite often and ask for IDs … because I look different” (Interview 3-51).

Due to these conflicts and the discrimination described above, living together in the neighborhood remains tense and insecure for most refugees. Particularly the hostility in the immediate living environment significantly restricts privacy and security. Some interviewees told us that due to the hostile atmosphere in the neighborhood, they often visit the inner city, where they feel more comfortable. They mentioned that it is easier to “blend in” in the inner city where they also feel more familiar and connected at the same time, due to social networks and various infrastructures that are more established there.

4.2.3 Social infrastructure: missing and emerging infrastructures

As already indicated, Gorbitz consists mainly of residential areas. However, social facilities such as schools and kindergartens are mostly within walking distance. Yet no refugee describes the existing social infrastructure (clubs, schools, kindergartens, shopping facilities, etc.) as diverse or migrant-oriented. In terms of access to social infrastructures, most of the interviewees experience language barriers and discriminatory treatment as the biggest obstacles. For example, communication in local institutions such as schools, kindergartens, doctors' offices, or government agencies is difficult due to a lack of multilingual services (e.g., staff or information materials), so the support they offer is limited. What we can see, however, is that in the instances where changes are made they result in an immediate improvement. One mother describes the introduction of multilingual staff in her child's school:

This year they have an Arabic professional in the school as a social worker … so that communication is possible in Arabic … I find that very good. (Interview 3-47)

Similarly, some interviewees state that they have found access to support and participation through local organizations offering for example children and youth social work or focusing on women's and girls' health. They offer counseling and translation, as well as initiate encounters in the neighborhood through meetings and events that also strengthen networks between refugees (e.g., cooking groups and family breakfasts). Again, language is a core factor as refugees emphasize that Arabic- or Farsi-speaking staff are key contacts for them and are missing in most other local institutions. One interviewee even describes such associations as crucial for her motivation to stay in the neighborhood:

There I could be in contact with Germans and with others … [The organization] is like my new family. And when the [organization] moves, I move with them (Interview 3-44).

4.2.4 Gorbitz – summary

In sum Gorbitz offers relatively good access to housing and therefore to a life outside of the restrictions of shelters. While many refugees – especially families – like the calmness of the neighborhood, many experience racist, hostile, and threatening encounters in public and semi-public spaces. With regard to the existing social infrastructures, the material shows that social workers in Gorbitz have done a great deal to open up the neighborhood and create, inter alia, multilingual offerings. These social infrastructures give access to support in an otherwise often hostile context. They provide important resources that enable refugees to network, organize their family life, and receive social support, among other things. Yet according to our material, they mainly reach families. Furthermore, other kinds of social infrastructure like school or kindergarten are places where refugees experience language barriers, discrimination, and exclusion.

Comparing Berlin-Kreuzberg and Dresden-Gorbitz, we see that both offer different conditions for arrival: Kreuzberg hosts a wide variety and mix of social infrastructures that support arrival processes by offering multilingual information and counseling and that connect people with one another. Such a mundaneness of diversity is also present in the way most refugees experience public space there. However, the area is characterized by a highly exclusive housing market. In Dresden-Gorbitz, on the other hand, many refugees found private housing, which offers access to privacy and a self-determined life. Public space, though, is in general experienced as hostile and dangerous, which also extends to semi-public spaces in public transport or apartment buildings. Refugees living in Gorbitz paint a mixed picture when it comes to social infrastructure like schools, kindergartens, neighborhood centers, and counseling services: while many local institutions are experienced as inaccessible due to language barriers and discriminatory experiences, there are others that offer support and that have established multilingual services since 2014/15. The latter were often experienced as supportive islands in an environment which is otherwise mainly perceived as hostile.

These two cases do not comprehensively cover the range of possible, existing, or dominant conditions encountered in arrival, nor did we cover all relevant dimensions of infrastructures that affect the arrival process. Still, what we can see from this comparison is that both contexts offer inclusive and exclusive infrastructural constellations which cannot be fully grasped if we were to label one or both of these neighborhoods as an “arrival area”. Instead, it is important, first, to not only focus on inclusive factors but also consider exclusive processes in the debate on and study of arrival. Second, it is crucial to identify which kind of infrastructure in a local context is inclusive or exclusive for recent immigrants and to what extent. Third, it is necessary to recognize in analyses that not all forms of inclusivity and exclusivity of local infrastructures work the same for all groups. In Kreuzberg, for example, Black refugees experienced more threats, hostility, and police checks than refugees from the Middle East, who have often reported being able to blend in in public space. Another example are multilingual services and the languages they do and do not offer. Furthermore, housing markets can be selective along racialized social boundaries, income groups, accessibility via social networks, or access to social welfare benefits. It is therefore important to include racialized and other social boundary processes in analyses of the role of infrastructures in arrival processes in order to understand which infrastructures offer access to resources and social mobility to whom.

If we do look not at whole areas but instead at specific local infrastructures and the way they affect arrival processes in inclusive as well as exclusive ways, we are able to, first, specify which kinds of infrastructures and infrastructural networks are important for arrival and how. Second, we are better able to see which kinds of infrastructures are helpful and provide resources for one category of people while possibly being dysfunctional for another. Such an infrastructural view on arrival processes is therefore instrumental to understanding who can access specific resources where and how this then affects the production of social inequalities and (im)mobility. However, going beyond immediate resource access and analyzing social inequality and (im)mobility require a longer-term perspective than the analysis in this paper is able to offer. Furthermore, all three kinds of infrastructure we looked at here, housing, public space, and social infrastructure, are embedded in processes and structures located outside the immediate neighborhoods. For a full analysis of how these infrastructures work, we would need to analyze the (translocal) networks as well as the meso- and macro-level processes within which they are embedded and co-produced. Questions that arise in this context are for example how recent immigrants get access to resources in different places or how the local processes in the two depicted neighborhoods are embedded in larger developments of asylum regulations, housing commodification, gentrification, segregation, deprivation, and structural racism. One relevant question would be, for example, how immigrants access support beyond their immediate residential neighborhood or if different immigrant groups rely on such extra-local support more often because of the social boundaries they encounter in their immediate residential environment (El-Kayed, 2018). We could see some indications of this in the interviews with refugees who do not live in Kreuzberg but come there frequently to use the support infrastructure present there. In our material we could not find examples for digital support structures, but especially after the COVID-19 pandemic it would be interesting to see if digitalization plays a role here and whether it can to some extent compensate for gaps in the local infrastructure or if digitalization increases existing support gaps instead of closing them (Berg, 2022).

The qualitative interview data contain highly sensitive information and are not publicly accessible. Please contact the authors regarding any questions you might have.

The conceptualization and writing of the article was jointly conducted by NEK and LK. Data curation was conducted by LK. The supervision of the research, project management, and writing (review and editing) were mainly done by NEK.

The contact author has declared that neither of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We would like to thank Ulrike Hamann, Yağmur Dalga, Camille Ionescu, and Sebastian Juhnke for their respective contributions to the broader research project on which this article is based. We thank our interpreters for the constructive collaboration and the interviewees for sharing their perspectives with us. We also thank two anonymous reviewers for their precise and helpful comments.

This research has been supported by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (grant no. 01UG1739X).

This paper was edited by Cristina Del Biaggio and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Amin, A.: Lively Infrastructure, Theor. Cult. Soc., 31, 137–161, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276414548490, 2014.

Angelo, H. and Hentschel, C.: Interactions with infrastructure as windows into social worlds: A method for critical urban studies: Introduction, City, 19, 306–312, https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1015275, 2015.

Barlösius, E., Keim, K.-D., Meran, G., Moss, T., and Neu, C.: Infrastrukturen neu denken: gesellschaftliche Funktionen und Weiterentwicklung, in: Globaler Wandel und regionale Entwicklung. Anpassungsstrategien in der Region Berlin-Brandenburg, edited by: Bens, O., Germer, S., Hüttl R. F., and Naumann, M., Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 147–173, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-19478-8, 2011.

Berg, M.: Information-precarity for refugee women in Hamburg, Germany, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Information, Commun. Soc., 7–8, 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2022.2129271, 2022.

Blokland, T. and Nast, J.: From Public Familiarity to Comfort Zone: The Relevance of Absent Ties for Belonging in Berlin's Mixed Neighborhoods, Int. J. Urban Reg., 38, 1142–1159, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12126, 2014.

BMI – Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat: Pressemitteilung vom 06.01.2016. Mehr Asylanträge in Deutschland als jemals zuvor, https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/pressemitteilungen/DE/2016/01/asylantraege-dezember-2015.html (last access: 22 February 2021), 2016.

Breton, R.: Institutional Completeness of Ethnic Communities and the Personal Relations of Immigrants, Am. J. Sociol., 70, 193–205, 1964.

Brücker, H., Kosyakova, Y., and Schuß, E.: Integration in den Arbeitsmarkt und Bildungssystem macht weitere Fortschritte, IAB-Kurzbericht 4/2020, IAB, 1–16, https://doku.iab.de/kurzber/2020/kb0420.pdf (last access: 26 July 2023), 2020.

Burgess, E. W.: Residential Segregation in American Cities, Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. SS., 140, 105–115, https://doi.org/10.1177/000271622814000115, 1928.

De Vidovich, L. and Bovo, M.: Post-suburban arrival spaces and the frame of `welfare offloading': notes from an Italian suburban neighborhood, Urban Res. Pract., 16, 141–162, https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2021.1952482, 2021.

Dunkl, A., Moldovan, A., and Leibert, T.: Innerstädtische Umzugsmuster ausländischer Staatsangehöriger in Leipzig: Ankunftsquartiere in Ostdeutschland?, Stadtforsch. Stat., 32, 60–68, 2019.

El-Kayed, N.: Local Conditions of Democracy – The relevance of neighborhoods for political participation of first and second-generation immigrants, Dissertation, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, 2018.

El-Kayed, N. and Hamann, U.: Refugees' Access to Housing and Residency in German Cities: Internal Border Regimes and Their Local Variations, Social Inclus., 6, 135–146, https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v6i1.1334, 2018.

El-Kayed, N., Bernt, M., Hamann, U., and Pilz, M.: Peripheral Estates as Arrival Spaces? Conceptualising Research on Arrival Functions of New Immigrant Destinations, Urban Plan., 5, 103–114, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v5i3.2932, 2020.

El-Kayed, N., Keskinkılıç, L., Juhnke, S., and Hamann, U.: Nachbarschaften des Willkommens – Bedingungen für sozialen Zusammenhalt in super-diversen Quartieren (NaWill), Abschlussbericht, BIM – Berliner Institut für empirische Integrations- und Migrationsforschung, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, 158 pp., https://doi.org/10.18452/22850, 2021.

Esser, H.: Ethnische Kolonien: “Binnenintegration” oder gesellschaftliche Isolation?, in: Segregation und Integration. Die Situation von Arbeitsmigranten im Aufnahmeland, edited by: Hoffmeyer-Zlotnick, J. H., QUORUM Verlag, Berlin, 106–117, ISBN 3-924725-01-2, 1986.

Felder, M., Stavo-Debauge, J., Pattaroni, L., Trossat, M., and Drevon, G.: Between Hospitality and Inhospitality: The Janus-Faced `Arrival Infrastructure', Urban Plan., 5, 55–66, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v5i3.2941, 2020.

Flamant, A., Fourot, A.-C., and Healy, A. (Eds.): L'accueil hors des grandes villes, Revue européenne des migrations internationales, 36, 7–27, https://doi.org/10.4000/remi.16908, 2020.

Florax, R. J., de Graaff, T., and Waldorf, B. S.: A Spatial Economic Perspective on Language Acquisition: Segregation, Networking, and Assimilation of Immigrants, Environ. Plan. A, 37, 1877–1897, https://doi.org/10.1068/a3726, 2005.

Forschungsverbund StadtumMig: Vom Stadtumbauschwerunkt zum Einwanderungsquartier, Herausforderungen und Perspektiven für ostdeutsche Großwohnsiedlungen, https://doi.org/10.18452/25294, 2023.

Franz, Y. and Hanhörster, H. (Eds.): Urban Arrival Spaces: Social Co-Existence in Times of Changing Mobilities and Local Diversity, 5, Urban Planning, Lisbon, https://cogitatiopress.com/urbanplanning/issue/viewIssue/183/PDF183 (last access: 26 July 2023), 2020.

Gardesse, C. and Lelévrier, C.: Refugees and Asylum Seekers Dispersed in Non-Metropolitan French Cities: Do Housing Opportunities Mean Housing Access?, Urban Plan., 5, 138–149, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v5i3.2926, 2020.

Gerten, C., Hanhörster, H., Hans, N., and Liebig, S.: How to identify and typify arrival spaces in European cities – A methodological approach, Populat. Space Place, 29, e04, https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2604, 2022.

Glorius, B., Bürer, M., and Schneider, H.: Integration Of Refugees In Rural Areas And The Role Of The Receiving Society: Conceptual Review And Analytical Framework, Erdkunde, 75, 51–60, 2021.

Haase, A., Schmidt, A., Rink, D., and Kabisch, S.: Leipzig's Inner East as an Arrival Space? Exploring the Trajectory of a Diversifying Neighbourhood, Urban Plan., 5, 89–102, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v5i3.2902, 2020.

Hamann, U., Karakayali, S., Wallis, M., and Höfler, L.: Erhebung zu Koordinationsmodellen und Herausforderungen ehrenamtlicher Flüchtlingshilfe in den Kommunen, Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh, https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/de/publikationen/publikation/did/koordinationsmodelle-und-herausforderungen-ehrenamtlicher- (last access: 26 July 2023), 2016.

Hanhörster, H. and Weck, S.: Cross-local ties to migrant neighborhoods: The resource transfers of outmigrating Turkish middle-class households, Cities, 59, 193–199, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.11.004, 2016.

Hanhörster, H. and Wessendorf, S.: The Role of Arrival Areas for Migrant Integration and Resource Access, Urban Plan., 5, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v5i3.2891, 2020.

Helbig, M. and Jähnen, S.: Wo findet “Integration” statt? Die sozialräumliche Verteilung von Zuwanderern in den deutschen Städten Zwischen 2014 Und 2017, WZB Discussion Paper P 2019-003, WZB, Berlin, https://bibliothek.wzb.eu/pdf/2019/p19-003.pdf (last access: 27 July 2023), 2019.

Hess, S., Binder, J., and Moser, J.: No integration?! Kulturwissenschaftliche Beiträge zur Integrationsdebatte in Europa, transcript Verlag, Bielefeld, ISBN 9783839408902, 2009.

Hess, S. and Kasparek, B.: The post-2015 European border regime. New approaches in a shifting field, Archivio Antropologico Mediterraneo, Anno XXII, 21, https://doi.org/10.4000/aam.1812, 2019.

Husseini de Arauìjo, S. and Kersting, P.: Welche Praxis nach der postkolonialen Kritik? Human- und physisch-geographische Feldforschung aus übersetzungstheoretischer Perspektive, Geogr. Helv., 67, 139–145, https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-67-139-2012, 2012.

Klinenberg, E.: Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life, Crown, New York, ISBN 9781524761172, 2018.

Lamont, M. and Molnár, V.: The Study of Boundaries in the Social Sciences, Annu. Rev. Sociol., 28, 167–195, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141107, 2002.

Landeshauptstadt Dresden Kommunale Statistikstelle: Bevölkerungsbestand, Tab. 8: Bevölkerung am Ort der Hauptwohnung nach Stadtteilen 1990 bis 2020, https://www.dresden.de/media/pdf/statistik/Statistik_1211_15-16_E2012-1990_nach_ST_und_Agr.pdf (last access: 4 October 2021), 2020.

Larkin, B.: The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure, Annu. Rev. Anthropol., 42, 327–343, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522, 2013.

Latham, A. and Leyton, J.: Social infrastructure and the public life of cities: Studying urban sociality and public spaces, Geogr. Compass, 13, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12444, 2019.

Lipsky, M.: Street-Level Bureaucracy. Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services, Russell Sage Foundation, New York, ISBN 9780871545442, 1980.

Low, S. and Smith, N. (Eds.): The Politics of Public Space, Routledge, New York, ISBN 9780415951395, 2006.

Marten, L,. Hainmueller, J., and Hangartner, D.: Ethnic networks can foster the economic integration of refugees, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 116, 16280–16285, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1820345116, 2019.

Mattissek, A., Pfaffenbach, C., and Reuber, P.: Methoden der empirischen Humangeographie, Westermann Schulbuchverlag, Braunschweig, ISBN 9783141603668, 2013.

McFarlane, C. and Rutherford, J.: Political Infrastructures: Governing and Experiencing the Fabric of the City, Int. J. Urban Reg., 32, 362–374, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2008.00792.x, 2008.

Meeus, B., Arnaut, K., and Van Heur, B.: Arrival Infrastructures. Migration and Urban Social Mobilities, Palgrave Macmillan, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91167-0, 2019.

Meeus, B., Beeckmans, L., Van Heur, B., and Arnaut, K.: Broadening the Urban Planning Repertoire with an `Arrival Infrastructures' Perspective, Urban Plan., 5, 11–22, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v5i3.3116, 2020.

Mehl, P., Fick, J., Glorius, B., Kordel, S., and Schammann, H.: Geflüchtete in ländlichen Regionen Deutschlands, Springer VS, Wiesbaden, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-21570-5_10-1, 2023.

Mokhles, S. and Sunikka-Blank, M.: `I'm always home': social infrastructure and women's personal mobility patterns in informal settlements in Iran, Gender Place Cult., 29, 455–481, https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2021.1873743, 2022.

Müller, A. L., Lossau, J., and Flitner, M. (Eds.): Infrastruktur, Stadt und Gesellschaft. Eine Einleitung, in: Infrastrukturen der Stadt, Springer VS, Wiesbaden, 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-10424-5_1, 2017.

Musterd, S., Andersson, R., Galster, G., and Kauppinen, T. M.: Are Immigrants' Earnings Influenced by the Characteristics of Their Neighbours?, Environ. Plan. A, 40, 785–805, https://doi.org/10.1068/a39107, 2008.

Nieuwenhuis, J., Hooimeijer, P., van Ham, M., and Meeus, W.: Neighbourhood immigrant concentration effects on migrant and native youth's educational commitments, an enquiry into personality differences, Urban Stud., 54, 2285–2304, https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016640693, 2017.

Phillimore, J.: Refugee-Integration-Opportunity Structures: Shifting the Focus From Refugees to Context, J. Refugee Stud., 34, 1946–1966, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa012, 2021.

Portes, A. and Bach, R. L.: Latin Journey. Cuban and Mexican Immigrants in the United States, University of California Press, Berkeley, ISBN 9780520050044, 1985.

Röder, A.: Integration in der Migratonsforschung, in: Handbuch Integration, edited by: Pickel, G., Decker, O., Kailitz, S, Röder, A., and Schulze Wessel, J., Spinger, Wiesbaden, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-21570-5_10-1, 2019.

Saunders, D.: Arrival city: How the largest migration in history is reshaping our world, Windmill Books, London, ISBN 9780307388568, 2011.

Schillebeeckx, E., Oosterlynck, S., and de Decker, P.: Migration and the resourceful neighborhood: Exploring localized resources in urban zones of transition, in: Arrival infrastructures: Migration and urban social mobilities, edited by: Meeus, B., Arnaut, K., and van Heur B., Palgrave Macmillan, London, 131–152, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91167-0, 2019.

Simone, A.: People as Infrastructure: Intersecting Fragments in Johannesburg, Publ. Cult., 16, 407–429, https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-16-3-407, 2004.

Star, S. L.: The Ethnography of Infrastructure, Am. Behav. Sci., 43, 377–391, https://doi.org/10.1177/00027649921955326, 1999.

Steigemann, A. M.: First arrivals: The socio-material development of arrival infrastructures in Thuringia, in: Arrival infrastructures: Migration and urban social mobilities, edited by: Meeus, B., Arnaut K., and van Heur, B., Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 179–205, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91167-0_8, 2019.

Tilly, C.: Social Boundary Mechanisms, Philos. Soc. Sci., 34, 211–23, https://doi.org/10.1177/0048393103262551, 2004.

Weiss, K.: Zuwanderung und Integration in den neuen Bundesländern, in: Handbuch Lokale Integrationspolitik, in: Handbuch Lokale Integrationspolitik, edited by: Gesemann, F. and Roth, R., Springer VS, Wiesbaden, 125–145, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-13409-9_6, 2018.

Wessendorf, S.: Settling in a Super-Diverse Context: Recent Migrants' Experiences of Conviviality, J. Intercult. Stud., 37, 449–463, https://doi.org/10.1080/07256868.2016.1211623, 2016.

Wilson, W. J.: The Truly Disadvantaged. The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, ISBN 9780226901268, 1987.

Wise, A. and Velayutham, S. (Eds.): Everyday multiculturalism, Palgrave Macmillan, London, https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230244474, 2009.

Zhou, M.: Contemporary Chinese America. Immigration, Ethnicity, and Community Transformation, Temple University Press, Philadelphia, ISBN 9781592138586, 2009.

The research project Welcoming Neighborhoods was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (project number 01UG1739X).

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Infrastructures in the context of arrival

- Methods

- Patterns of inclusion and exclusion in local infrastructures

- Discussion: local infrastructural constellations of inclusion and exclusion

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Infrastructures in the context of arrival

- Methods

- Patterns of inclusion and exclusion in local infrastructures

- Discussion: local infrastructural constellations of inclusion and exclusion

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References