the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Book review: Bornées. Une histoire illustrée de la frontière/Along the Line. Writing with Comics and Graphic Narrative in Geography

Dolorès Bertrais

Giada Peterle

- Article

(1240 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Fall, J.: Bornées. Une histoire illustrée de la frontière, Éditions Métis Presses, 152 pp., ISBN 978-2-940711-49-9, 2024.

Fall, J.: Along the Line. Writing with Comics and Graphic Narrative in Geography, EPFL Press, 232 pp., EAN13 9782889156818, 2025.

Partir à la découverte de la frontière genevoise, voilà ce que propose Bornées. Une histoire illustrée de la frontière, afin de renouer avec une géopolitique territoriale du quotidien. À travers des pérégrinations à vélo et à pied, cet essai graphique nous embarque dans un jeu de piste qui prend la forme d'une « chasse-poursuite » (p. 104). Il invite à (re)découvrir ce qu'habiter un territoire transfrontalier signifie par le prisme de l'objet frontière, à la fois visible et invisible, matérialisé ou non. En plaçant la frontière au cœur de sa pensée, Juliet Fall, géographe et professeure à l'Université de Genève, s'interroge sur « le où, le quand, le comment et le pourquoi de la frontière » (ibid.). La méthode qu'elle déploie pour y parvenir se révèle assez habile. Richement illustré de visuels qui jalonnent le récit, cet ouvrage procure un certain plaisir à la lecture, notamment vers la fin.

Destiné au grand public, l'ouvrage rappelle que, parler de frontières, c'est explorer un univers à la fois sensible et complexe. Le format graphique allège la gravité de ces thématiques sans en altérer la profondeur. Pour autant, sur le plan théorique, peu de concepts propres à la discipline de la géographie émergent au fil des pages. L'auteure précise dès l'avant-propos que Bornées est accompagné d'un ouvrage plus académique et méthodologique, Along the Line: Writing with Comics and Graphic Narrative in Geography (p. 13), rédigé en anglais et pensé pour un public spécialisé. Le choix de l'anglais, langue plébiscitée dans le monde académique, illustre ici une démarche assumée de s'adresser essentiellement à ses pairs, offrant un contrepoint complémentaire à l'approche accessible et sensible de Bornées.

L'ouvrage Bornées se compose de trois parties d'une richesse et d'une longueur inégales, transportant les lecteurs ⋅ ices à des rythmes temporels et historiques différents, où la géographe occupe la place de personnage principal de l'histoire.

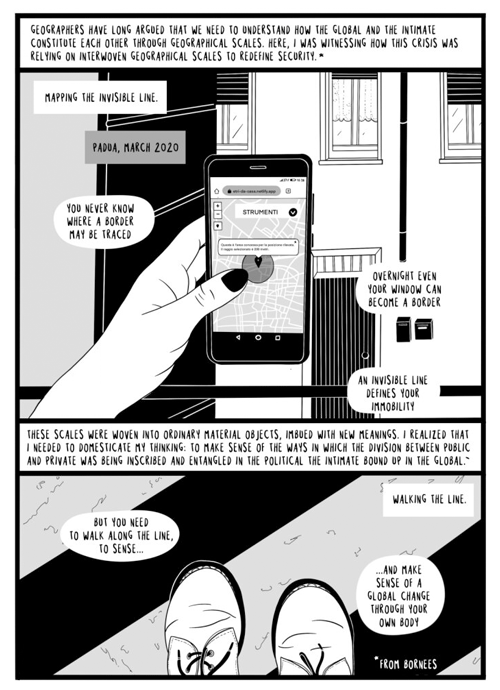

1.1 Quand la pandémie matérialise l'invisible

La première partie, intitulée « La frontière fermée » (pp. 14–81), invite les lecteurs ⋅ ices à découvrir une réflexion intime et sensible issue de l'expérience personnelle de l'auteure durant le semi-confinement en Suisse. Dès les premières pages, Juliet Fall nous plonge dans un « conte en images sur le territoire, les identités et les efforts consentis par les États pour nous faire croire qu'ils sont indispensables » (p. 17). Cette entrée en matière autobiographique, teintée d'incertitudes et de peurs liées à la pandémie, devient sous sa plume une opportunité méthodique et réflexive pour interroger la frontière du canton de Genève pour ce qu'elle est : une « ligne imaginaire » traversant un territoire d'entre-deux, marqué parfois par sa gestion matérialiste et ses ambiguïtés qui alimentent « cette petite géopolitique quotidienne » (p. 63).

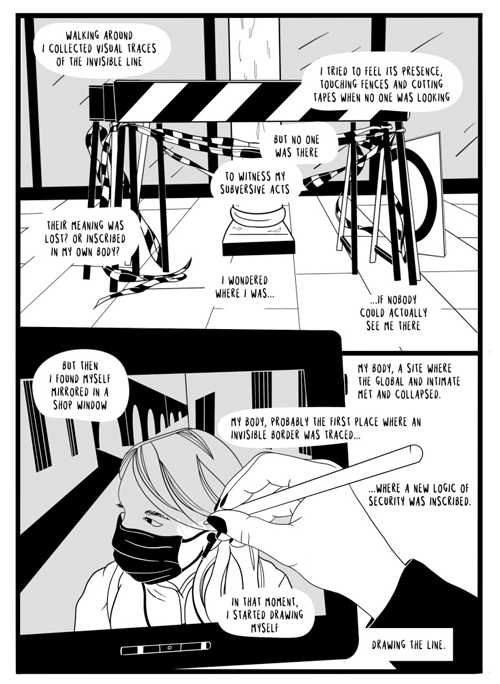

Les récits, ancrés dans le quotidien, révèlent des scènes où la frontière, habituellement discrète, se matérialise de façon saisissante. Tandis que les anciens bâtiments de douane subsistent comme des témoins d'un passé frontalier, la crise sanitaire les réactive par des ajouts prosaïques, mais évocateurs : blocs de béton, ganivelles, rubans rouges et blancs, ou cônes de signalisation. Ces artefacts, banals en apparence, deviennent de puissants symboles de contrôle et de surveillance, rappelant combien la frontière est une construction sociale incarnée dans le paysage.

Malgré cette approche prometteuse, la tonalité subjective et autobiographique adoptée dans cette première partie peut parfois manquer de profondeur analytique. Certaines descriptions, bien que poétiques, frôlent l'exagération et laissent celles et ceux qui lisent l'ouvrage un brin sceptiques. Par exemple, la scène de camping dans le salon ou cette formule dramatique : « La zone est déserte. Il n'y a personne. Nous sommes seuls au monde. Naufragés du bout du monde, dans un silence de plomb » (p. 44), risquent d'affaiblir l'impact des réflexions sous-jacentes. De même, des passages comme « le paysage est devenu notre unique cadre de référence, comme un texte rédigé dans une langue difficile à décoder » (p. 46) peinent à trouver un écho universel.

Cependant, à mesure que les pages se tournent, l'auteure parvient à insuffler au récit une épaisseur plus captivante. Un exemple marquant reste celui du cimetière israélite de Veyrier, où l'auteure y analyse la frontière non seulement comme une ligne de division, mais aussi comme un espace protecteur, affirmant que « les territoires sont ce que nous choisissons d'en faire : des lieux d'exclusion et de sécurité » (p. 69). Cette perspective ancrée dans le paysage donne une dimension tangible aux concepts explorés, et c'est à partir de là que l'intérêt des lecteurs ⋅ ices pour l'ouvrage s'intensifie. En somme, la première partie de Bornées se distingue ainsi par son ambition de mêler sensibilité autobiographique et observation géographique. Si le début peut sembler hésitant, Juliet Fall parvient, à travers des exemples concrets, à rendre la frontière visible et signifiante, transformant le banal en matière à penser.

1.2 Une plongée historique enrichissante

La seconde partie, intitulée « Fabriquer la frontière » (pp. 81–111), s'attarde sur les fondements historiques et juridiques des frontières genevoises, en remontant aux traités de Paris (1814, 1815) et de Turin (1816). Juliet Fall y décortique les enjeux géopolitiques, stratégiques et militaires qui ont façonné ces délimitations, tout en explorant leurs répercussions sur la configuration du canton de Genève. Cette section, étayée par une documentation abondante et enrichie d'illustrations dont l'intensité graphique accompagne le dynamisme du propos, s'appuie sur une analyse minutieuse des archives, notamment les procès-verbaux de délimitation de 1825, ainsi que sur des cartes anciennes issues des Archives d'État genevoises (pp. 98–110). À travers l'étude des traités et des cartes anciennes, Juliet Fall montre toutefois que ces documents « ne racontent que la moitié de l'histoire » (p. 103), invitant ainsi à combler ces silences en parcourant le terrain et en confrontant le passé au présent. C'est pourquoi l'auteure approfondit sur le terrain le rôle des bornes et autres marques territoriales, non seulement comme outils de contrôle, mais aussi comme témoins matériels des choix géopolitiques du XIXème siècle.

En adoptant une posture subjective pleinement assumée, l'auteure qualifie cette exploration de géographie incarnée ou encore de « géographie vagabonde » (p. 92). Refusant les vérités absolues et les bases historiques inébranlables, elle revendique une approche lente et réfléchie : « Je ne cherche pas de vérités territoriales, mais à comprendre pourquoi et comment les humains se forgent une place dans le paysage » (ibid.). Cette réflexion méthodologique, qui pourrait être rapprochée de l'éthique du slow science, confère à l'ouvrage une dimension résolument humaine et sensible, où l'acte d'arpenter le territoire devient une manière de renouer avec l'histoire, mais aussi de questionner notre rapport au monde. Cette quête personnelle trouve écho dans des anecdotes simples, mais évocatrices, comme cet aveu : « Même si je n'avais jamais vraiment voulu y aller avant, j'ai désormais envie d'explorer tous les chemins et sentiers » (p. 85). En soulignant le désir d'arpenter un territoire dont la libre circulation fut temporairement suspendue, l'auteure illustre comment la privation peut éveiller une curiosité et une soif d'exploration, rappelant que de l'interdit naît une forme de désir.

1.3 Au-delà des frontières?

La troisième partie, intitulée « Maintenir la frontière » (pp. 111–146), examine les dispositifs politiques qui perpétuent ou transforment les frontières dans le temps. L'auteure rappelle ainsi que « les changements se font au rythme du politique, pas de la technique » (p. 112). Si cette citation met en lumière la capacité des frontières à évoluer, notamment à travers des négociations historiques, ce récit aurait gagné en profondeur en mobilisant également les travaux en Science and Technology Studies. Ces derniers auraient permis de mieux comprendre comment les frontières se situent à l'intersection de la technique, du politique et du social, car les décisions politiques sont toujours médiées par des infrastructures et des technologies qui matérialisent les volontés géopolitiques des États. Les frontières sont aussi des artefacts techniques. Elles s'incarnent dans des dispositifs matériels et immatériels qui encadrent les mobilités et définissent des espaces d'inclusion/exclusion, tels que les infrastructures matérielles (murs, postes de contrôle), les technologies de surveillance (biométrie, drones) et les frontières numériques (bases de données, visas électroniques).

Pourtant, ces réflexions sur les assemblages sont amorcées dans le récit graphique, notamment lorsque la géographe décrit la frontière comme un objet fluide, insaisissable, à l'image des cours d'eau qui n'ont que faire de la surveillance de l'État. Cette métaphore invite à penser la frontière non seulement comme une limite tangible, mais aussi comme un phénomène mouvant et indomptable. Toutefois, l'anthropocentrisme domine dans cet ouvrage, réduisant le terrain à une perspective majoritairement humaine. Une approche post-humaniste des frontières, qui envisagerait ces espaces comme des assemblages plus qu'humains dotés d'un pouvoir politique (voir par exemple Oliveras-González, 2023), aurait pu élargir encore la portée du propos. Si cette dimension est évoquée, elle demeure sous-exploitée. Par ailleurs, l'étude aurait bénéficié d'une analyse plus détaillée des acteurs contemporains qui participent à la matérialisation, à la transformation ou à la transgression des frontières. L'autrice elle-même reconnaît cette limite en confiant : « Je parle beaucoup aux choses, mais peu aux personnes » (p. 128). Cette absence réduit quelque peu la portée sociale de son étude, en omettant de considérer les pratiques des individus et des collectifs qui façonnent ou contestent les frontières au quotidien.

Dans les dernières pages, Bornées évolue vers un récit photohistorique qui culmine dans une réflexion forte sur les frontières comme espaces ambivalents, capables à la fois aussi de « sauver » et de résister (p. 68, p. 139). La conclusion, poignante, interroge les traces que nous choisissons de laisser et rappelle que toute histoire est située et orientée selon le point de vue de celui ou celle qui la raconte. Ainsi, l'une des phrases finales « rendre réelle cette ligne invisible » (p. 144), illustre ce retour au concret : la frontière n'est pas qu'une abstraction cartographique, elle façonne aussi les vies qu'elle traverse (p. 145). C'est à partir de cette réflexion que mes pensées se lient naturellement au propos de l'ouvrage. Dans un monde post-Covid, les frontières, que l'on pensait abolies ou fluidifiées dans certains espaces comme l'espace Schengen, réapparaissent avec force. Qui aurait imaginé, par exemple, que l'Allemagne rétablirait des contrôles frontaliers pour une durée de six mois en septembre 2024, dans un contexte marqué par la forte progression de l'extrême droite? À l'heure où j'écris ces mots, nous commémorons les 80 ans de la libération des camps d'Auschwitz-Birkenau, et cette juxtaposition souligne combien les frontières, loin d'être des lignes neutres, sont aussi des lieux de mémoire, de lutte et de responsabilité collective. Bornées s'achève sur une note universelle et critique, élargissant le débat aux questions contemporaines, en particulier celles et ceux qui, aujourd'hui encore, se heurtent aux murs et aux politiques d'exclusion.

I must admit that, as a child, I never understood my brother's obsession with comics. They were too messy for my taste, the order of the speech bubbles never quite clear. I preferred the linear and ordered logic of novels and “normal” books. You could say that my longing for linearity and order was an expression of the modernist thinking of the post-Cold War era in which I grew up. This modernist thinking shaped not only my preference for linear books, but also my world view at that time. The fall of the Berlin Wall was one of my first political memories, and I grew up believing in the linear development of a kind of progressive politics. I was convinced back then that if one wall fell, it would be only a matter of time before one wall after another would come down until we would all live in a “global village” or at least a European Union without borders.

We all know that the fall of the Berlin Wall was not the end of the history of borders and that the world has become even more chaotic and unpredictable since then. Juliet Fall, Professor of Geography at the University of Geneva, helps us to grapple with this new world order characterised by the rise of nationalist populism, the increasing securitisation of borders as a consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic and what is often called the “migration crisis”. Her new comic book Bornées takes the closure of the border between Switzerland and France in March 2020, in the context of the global pandemic of the Covid-19 virus, as a starting point to question the current politics of intensified and often militarised borders.

The comic begins with a vivid and auto-ethnographic account of how the first Covid-19 blockade and the closure of the French–Swiss border were experienced by Juliet Fall and her family. Focusing on the improvised border installations that made the otherwise invisible line visible, the first part of the comic gives an embodied and situated account of how the closing of borders, or rather the process of bordering, and its material effects were experienced during the lockdown. It shows how the national politics that aimed to respond to the global pandemic affected the intimate spheres of the home, of the family and of social life. The second part deals with the way in which this border is demarcated through border stones, based on walks from border stone to border stone. It provides an insight into the political disputes and the material making of the border. The third section focuses on the maintenance required to keep the border and its infrastructure in place, looking at the people who carry out this maintenance and care of the border. It is the long-term invisibility of the border between the canton of Geneva in Switzerland and France that makes this case study rich for exploring the politics, materialities and everyday practices of making and securing borders. The political ambition of the book and Juliet Fall's own political positioning become clear when she writes that the book is “a declaration of love to invisible lines; a hymn to transgression and belonging”. This “declaration of love” for lines and transgression makes the comic book a great alternative teaching resource in (political) geography, political science, anthropology and related (interdisciplinary) fields to aid in understanding that borders are far from natural and rather the outcome of politics, everyday practices and national imaginaries. But as it is written in a very accessible and entertaining way, it is in fact very stimulating reading not only for people who share this academic fascination with more or less visible lines that demarcate our world but for anyone who has a hard time making sense of our turbulent political times.

Bornées succeeds in revealing the absurdity of borders. One of my favourite lines of the comic is Juliet Fall's reflection that “recounting each stage [of our trips to the border] is a way of making sense of the poetic absurdity of the line, in images and words”. By asking questions – such as why setting up concreted blocks and closing borders is supposed to help “to catch a virus” or why, if the bodies of the people closest to us are the main treat of contagion, is the closing of international borders considered to be a solution to fight the Covid-19 virus – she reveals through her images and words the absurdity of border politics.

The comic book does a fascinating job in showing through its very rich ethnography how borders are made and maintained, arguing that state territories and borders are the result of careful (re)enactments of everyday practices and material assemblages. The comic invites readers to question any naturalisation of borders by highlighting the mundane labour required to maintain territorial boundaries. The bike rides to the closed border during the pandemic and the long walks to find the border stones (bornes) are a creative way of engaging with the way borders are made. “Customs, bodies, new rules and barriers that open and close” – all contribute to the creation of new infrastructures of power in territories in transition. But Juliet Fall's insights go beyond the moment of the pandemic, as she helps us to understand that “the abstract lines on the maps are not made and maintained by military power, but by the care lavished and recorded over centuries”. This care for the border is carried out by geometers, engineers, town planners and technicians who help to create and maintain the line using maps and digital databases. This human work of installing border stones and concrete infrastructures also makes use of nature – rivers, trees, ditches and fields – to realise the nation state's political ambition of a sovereign territory.

Despite the importance of natural boundaries such as rivers to mark borders, the comic insists, with much empirical detail, that borders are not natural but constructed over centuries, feeding our “geographical imaginations” (Gregory, 1994). The Covid-19 pandemic makes the sorting function of the border visible, or as Juliet Fall beautifully puts it, “This mundane geopolitics works by sorting people. Who is useful? Which bodies are really essential, and where and when should they be?” Insights into the exceptional state of the global pandemic make the border visible as a “sorting machine” (Mau, 2022). Juliet Fall's walk in search of the border stones reveals many histories of this sorting function of the border. One of them is the story of Irène, who helped Jewish refugees escape Hitler's anti-Semitic policies with a house that had a front door on Swiss territory and a back door on French territory. “Irène chose to use the border to save, not to kill”, writes Juliet Fall, reminding us of the necropolitical geographies of borders (Wright, 2011; Davies et al., 2017). The comic helps to interrogate the intimate geographies of European and global border politics that cause deaths and kill hopes of a better life on the other side of the line. But by showing how borders are made and maintained, it also allows us to contest the political, material and everyday practices of bordering and to rethink border politics that facilitate life rather than extinguish it (Anonymous, 2012).

For me, the merit of Juliet Fall's comic book lies in developing and experimenting with a new way of doing research and writing that responds to calls for embodied and situated knowledge production (Haraway, 1988; Harding, 1991) and takes seriously the fragility of the contemporary world. Her work contributes to the creative turn in geography by offering a new way of thinking about territory through the use of visual methods, digital graphics programs and the creative format of the comic. It also challenges and shows ways out of the current logics of academic knowledge production, which are characterised by the pressures of large-scale funding, “fast” publication and hyper-productivity, leaving little room for passion, inductive and open research processes, and work–life balance. It is an exemplary account of how to integrate visual and creative methods, not only for science communication, but as a fundamental approach to rethinking academic research and writing. Reading the comic as an academic interested in creative methods, I was curious to know more about the challenges of not only conducting the research itself but also the decisions Juliet Fall has made with regard to the selection of imagery, colours, shapes and design as well as how the creative work has shaped the arguments made in the book. I wondered what readers without a background in geography or political science take from the book and how it helps them to understand key concepts of these disciplines like sovereignty, nationalism or borders.

As a scholar interested in pushing the boundaries of research methods, academic writing and science communication to make visible the intimate, personal and messy making of the research process and of the world, I cannot emphasise enough the ground-breaking contribution the comic makes to pushing the boundaries of feminist geopolitics, creative methods and academic knowledge production. It does so in an incredibly creative, sophisticated and non-linear way that captures the chaotic and messy nature of our times. Brilliant – read it, share it, love it!

Looking, making, holding the line. But also, walking along the line, trying to sense and make sense of the border as an intimate and social, material and symbolic infrastructure in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic: this is where the story and the research project at the basis of Juliet J. Fall's book Along the Line. Writing with Comics and Graphic Narrative in Geography begin. In fact, in Fall's work it is impossible to separate the “story” – the narrative, auto-ethnographic, mundane and intimate narrative of life during the lockdown in Switzerland – from the research process: they go in parallel, literally proceeding together step by step, along the line of the border that separates Switzerland and France at the doors of Geneva, where the author and her family live. In his history of lines, Tim Ingold suggests considering them as dynamic traces that ask to be performed and followed. Likewise, in Along the Line the drawn line is never presented as a static trace on a map. For Fall, a line is an invitation to move, a pathway to cross, a geopolitical infrastructure to question through bodies and gestures, and even a plotline of a story (or a plurality of stories) to tell.

The book is organised in three parts, each based on the dialogue between comics and more traditional textual academic chapters: the whole work explores the Franco-Genevan border, starting from personal experiences collected through the use of visual methodologies and materials, from photography to drawing and mapping. In particular, the Covid-19 pandemic and related border closures are read by Fall as a context that made visible, and thus readable, the often-unnoticed infrastructure and social practices that construct and maintain political boundaries. Discussing the theoretical implications of this experience, the author engages with concepts from political geography, feminist studies and infrastructure theory to understand the fragile and constructed nature of territory and the intimate and social aspects of infrastructures. The book is also a discussion of the methodological possibilities offered by visual methods to engage with complex geographical discourses. Besides comic stories, Fall explains the correlation between the focus and process of her research and the comic form in the more traditional written chapters of the book. In “Fieldwork and research design”, she reflects on the connection between personal experience in the Covid-19 context and geographic research, stressing how spontaneous moves and more structured theoretical and methodological choices contributed to the design of this research. Also, in this chapter she shows how to work with a mixed-visual methodological approach, bringing photography (and rephotography), journaling, sketching and mapping together. In the second chapter, “Thinking visually about territory”, Fall focuses on the fragility of territory, moving beyond the so-called natural conception of borders to think of these lines as something that needs to be constantly rediscussed, embodied and materially rebuilt through infrastructural technologies. Finally, in “Writing with comics” the author explicitly reflects on the comic as a way to conduct geographical research differently: graphic research, in her words, is a way for “writing in the world, not on it” (p. 203), thus, a way to embrace a situated perspective as a form of critical thinking. Moreover, the radical openness of the comic language changes the way in which geographical thought takes place through a collaborative recomposition of meaning that engages both authors and readers: using comics, geographical knowledge production is presented as an ongoing and dialogical process. In comics, meaning is often hidden in the blank spaces in between panels and, thus, it asks to be actively researched.

At the beginning of Fall's journey, the practice of “beating the bound”, at the basis of the historical trace of the border, was taken literally by Fall, who found herself performing the geographical experience of walking: this way, it was possible for her to recognise how the border “builds a shared sense of community” (p. 94) that is worth exploring. Despite the passing of time and the presence of digital cartographic projections that allow us to visualise borders on our devices both from above and even through a horizontal pedestrian-like perspective (through Google Street View, for example), Fall shows us how much it is necessary to embody the map, to literally touch the border in order to understand the impact of these infrastructures. Nowadays more than ever, touching the material presence of political and administrative infrastructures is a way both to sense them, which means to feel physically and emotionally the border as something familiar and close, and to make sense of them, namely, to understand their geopolitical relevance and impact on different scales.

In Along the Line, the extraordinary context of the pandemic triggers a story that is nevertheless able to move beyond that specific and tragic spatio-temporal situation, to explore more in general how the global and the intimate constitute each other and how landscapes can be materially changed to inscribe tales of insecurity–security, protection–vulnerability and openness–closure. Along the Line is an original, creative and solid theoretical and methodological contribution to different contemporary debates in geography: it is informed by the long-lasting discussion about geography as a visual discipline and the more recent “creative return”; it speaks to feminist approaches and infrastructural thinking; it contributes to contemporary more-than-human geographies and geopolitics. Moreover, it is part of an emerging set of practices named comic-based research (CBR) that are growingly engaging researchers in different disciplinary fields, including the social sciences and geography (see, e.g., Cancellieri and Peterle, 2021; Kuttner et al., 2021; Peterle, 2021). After having been, together with Jason Dittmer (2010, 2014), one of the leading voices that defined the field comic book geographies, Fall now joins the ongoing debate on CBR as an author. After disparate articles published in comic form, or including comic pages, with Along the Line she comes to experiment with the book length as a geographer and comic author. This passage is relevant in terms of both the form and the content of her story. Whereas the form benefits from the possibility of creating a recurring colour palette that helps readers recognise the presence of the border and its symbolic materialities, in terms of content, working on a longer story allows her to think visually through comics about several key concepts in contemporary geography, such as border, scale, body and infrastructure. What is brilliant in Fall's work is indeed her capacity to engage with a new language to add complexity to geographical thinking: Along the Line is a perfect way to demonstrate how working with comics does not necessarily mean simplifying geographical discourses. On the contrary, she turns the apparent limits of comics into the possibility of telling geographical tales differently and posing new spatial questions.

Along the Line is in all respects a “research comic”, because it is a comic book composed while doing research and not simply created to represent it. As Fall explains, the composition of the comic book is not the result but rather a significant part of the author's research path: in fact, the comic book and the research process influence each other, in terms of how she collects materials, organises her archives and visually structures her own thinking. As geographers working with graphic narratives maintain, comics as a research practice have an impact upon the form of research outputs, which is probably the most visible part of how they influence geographical research, but they affect in the first place how this research is conducted, designed and performed. Also, the use of comics invites authors to make narrative choices that become relevant questions in terms of the poetics and ethics of geographical research. In Along the Line, for example, the comic's language allows the author to make formally visible and readable, through her own presence on the page, the conception of the “global intimate” that lies at the foundation of her analyses of borders as multiscalar infrastructures. Similarly, the way in which personal practices of care, intimate worries, and political national and international decisions mingle in Fall's narration helps us understand transcalarity, “sensing scale” as something that is not only domestic, intimate and embodied, but also global and social.

To conclude, in Along the Line the conception of the global intimate is a topic of discussion as much as a writing style and narrative approach to geographical storytelling. The decision to look inwards, bringing her individual experience to the fore, is the expression of the author's positionality, who is inspired by feminist geographers and chooses to make explicit the connections between the personal and the political: in this sort of “spontaneous auto-ethnography” that produces a form of autographic or visual auto-ethnography (p. 96), Fall, with her fragilities and hopes, becomes the visible protagonist of the story. Visually inhabiting the comic page, with a realistic style that reproduces almost photographically the clothing, the body and gestures, the facial expressions, and the small changes from day to day, Fall makes the audience aware of the active role and subjective presence of the researcher in the field. In Fall's work, there is no staging of an often desired objectivity of the scientific research process; on the contrary, she firmly presents the tours and detours of academic research, showing how much personal trajectories, imaginaries, memories, bodily experiences and relations influence the field (including how we choose the object of our research or the methods, timing and design of the research process). Even if Along the Line started “as an unplanned and improvised family experience” (p. 97), with digital photos and other visual materials collected in an unorganised archive, it soon appeared as a growingly intentional project, where the spatio-temporal context had a relevant role. This book represents a further step into the possibility of working with research-based comics in geography, showing how the use of graphic narratives provides us with methodological opportunities and limitations. It comes from a situated and intimate perspective and will certainly be enriched by all those other stories that are not included in the book and that will probably emerge through its multilingual publication and circulation. In fact, whereas Fall's book remains a critical yet personal testimony, it will function as a collector of stories that may be worth presenting in a future development of the project. Far from being an individualistic tale of the pandemic, Fall's book brings the global into the intimate, and vice versa: moving along the “drawn line”, readers sense and make sense of critical geographical concepts, like border, infrastructure, scale and home, through the practice of listening to others' stories and, maybe, welcoming the invitation to tell their own. The two comic pages that follow welcome this invitation and trace a possible line to follow and to explore the plurality of voices, gazes and pathways along borders.

Anonymous: A No Borders Manifesto, https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/a-no-borders-manifesto (last access: 9 March 2025), 2012.

Cancellieri, A. and Peterle, G.: Urban research in comics form: Exploring spaces, agency and narrative maps in Italian marginalized neighbourhoods, Sociologica, 15, 211–239, https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.1971-8853/12776, 2021.

Davies, T., Arshad, I., and Surindar D.: Violent Inaction: The Necropolitical Experience of Refugees in Europe, Antipode, 49, 1263–1284, https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12325, 2017.

Dittmer, J.: Comic book visualities: a methodological manifesto on geography, montage and narration, T. I. Brit. Geogr., 35, 222–236, 2010.

Dittmer, J. (Ed.): Comic book geographies, Franz Steiner Verlag, ISBN 9783515102698, 2014.

Gregory, D.: Geographical Imaginations, Blackwell,1994.

Haraway, D.: Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective, Feminist Stud., 14, 575–599, 1988.

Harding, S.: Whose Science? Whose Knowledge? Thinking from Women's Lives, Cornell University Press, 1991.

Kuttner, P. J., Weaver-Hightower, M. B., and Sousanis, N.: Comics-based research: The affordances of comics for research across disciplines, Qual. Res., 21, 195–214, 2021.

Mau, S.: Sorting Machines. The Reinvention of the Border in the 21st Century, Wiley, 2022.

Oliveras-González, X.: Beyond Natural Borders and Social Bordering: The Political Agency of the Lower Rio Bravo/Grande, Geopolitics, 28, 533–549, https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2021.2016706, 2023.

Peterle, G.: Comics as a research practice: drawing narrative geographies beyond the frame, Routledge, ISBN 9780367524654, 2021.

Wright, M. W.: Necropolitics, Narcopolitics, and Femicide: Gendered Violence on the Mexico-US Border, Signs, 36, 707–731, https://doi.org/10/cs677x, 2011.