the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

No people, no problem – narrativity, conflict, and justice in debates on deep-seabed mining

Oscar Schmidt

Manuel Rivera

While the idea of extracting deep-seabed resources dates back to as early as the 1960s, it remained pure fiction for decades due to limited technical possibilities and prohibitive costs. In recent years, against the backdrop of changing technical possibilities and a persistently high demand for raw materials, deep-seabed mining (DSM) has returned to the international political agenda. While numerous fact-finding missions engage in mapping the ocean's resources and public–private partnerships prepare to make an active engagement in mining the seabed, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) is entrusted with the development of a legal framework for possible future mining in accordance with the requirements defined under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The preparations for DSM are accompanied and ultimately shaped by a discourse on possible opportunities and risks of mining the deep seabed. The paper at hand traces dominant discursive positions and their narrative structures as a way of explaining the relative success or failure of DSM proponents who speak in favor of mining the seabed and DSM critics who warn against its striking environmental impacts and inestimable risks. We proceed from the observation that the historic discourse on the deep sea beyond national jurisdiction was rooted in what we call “narratives of promise” regarding global procedural and distributive justice, environmental health, and peaceful international cooperation. Our findings show how in today's debates the theme of global marine justice, which dominated the historic DSM discourse, is close to a “nonstory”. DSM is commonly narrated as a merely technocratic and apolitical process that appears to be free of social and environmental conflict. We conclude by arguing that to arrive at more successful critical narratives on DSM will require more pronounced depictions of the negative consequences in particular for humans, exposing the “politics” in DSM policy making and developing more competitive stories on alternatives to DSM.

- Article

(242 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

There can be no doubt that an effective international regime over the seabed and the ocean floor beyond a clearly defined national jurisdiction is the only alternative by which we can hope to avoid the escalating tensions that will be inevitable if the present situation is allowed to continue. It is the only alternative by which we can hope to escape the immense hazards of a permanent impairment of the marine environment. It is, finally, the only alternative that gives assurance that the immense resources on and under the ocean floor will be exploited with harm to none and benefit to all. (UN General Assembly, 1967b, Sect. 3)

These words, spoken by Maltese ambassador Arvid Pardo before the United Nations half a century ago, indicate the initial parameters of a discourse about deep-sea usage and regulation which unfolded over the subsequent decades, reaching its most important legal expressions in the endorsement of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the establishment of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) in 1994. They articulate three main concerns: preservation of the marine environment, fair distribution of risks and benefits associated with the exploitation of its resources, and peaceful stability in the international relations that frame their appropriation. All in all, Pardo managed to embed these motives into a very – today we must say excessively – optimistic picture that painted the “vastness of […] untapped wealth” lying on and beneath the seafloor and tinged it with a range of fantastic innovations, from submarine fish farms behind air-bubble curtains to floating conduits that would transport phosphorus deposits over great distances. Some of these innovations he thought to be “imminent” (UN General Assembly, 1967a:4–5), which in retrospect was quite unrealistic, yet his big picture still holds attractiveness and truth-value today, namely: a deep sea which, if treated as a “common heritage of mankind”, is a promise of global equity in both procedures and material benefits while, when falling prey to vested and hegemonic interests, it runs the risk of becoming overexploited, polluted, and militarized. The connection established here between the prospect of deep-seabed mining (DSM) and questions of global procedural and distributive justice locates DSM in the area of a much broader scholarly debate on environmental justice – or for that matter on marine justice (e.g., Schlosberg, 2007; Walker, 2012; Martin et al., 2019). The concept of Marine Justice in particular focuses on fair and democratic decision-making processes regarding the benefits and costs of the use of marine resources. Authors such as Martin et al. (2019) emphasize that to answer what procedural and distributive justice can look like in marine socioecological systems, a context-specific perspective is required. This relates in particular to those systems' constitution and dynamics related to space, time, knowledge, participation in decision-making, and enforcement (Martin et al., 2019).

An analysis of the discourse on DSM1, as it is carried out in this paper, addresses the question of whether and to what extent DSM can in fact be characterized and communicated as part of these broader debates. Our paper departs from the prima facie observation that modern discourse about the deep sea beyond national jurisdiction was rooted in what we call “narratives of promise”, promises of innovation-driven wealth, its globally fair distribution, environmental health, and peaceful international cooperation. We are puzzled by the fact that, during the formation of a very peculiar discourse centered on the pros and cons of DSM, the motives of distributive and procedural global justice seem to have lost their central place. While the question of benefit sharing retains a prominent place in the current political negotiations on the governance of DSM at the ISA, it no longer serves as the central discursive leitmotif, i.e., as the ultimate justification for an involvement in DSM. Instead of taking on the character of a promise, even a contested one, the idea of benefit sharing merely appears as a legal obligation imposed on today's policy makers by the historic decision to declare “the seabed and ocean floor and subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction” and the “common heritage of mankind” (UNCLOS, 1983:26ff.). Beyond highly technical publications, and the regular reminder that the common heritage of mankind must somehow be addressed, there is hardly any meaningful reference made to the question of who shall benefit and who will experience losses through DSM. Rather than representing an end in itself, marine justice appears as only one in a number of legal obstacles that need to be dealt with in the course of organizing the future of DSM.

While thus departing from the historic focus on procedural and distributive justice, today's advocates and opponents of DSM both turn to “narratives of necessity”, invoking global sustainability either as a justification for the kind of appropriation Pardo had warned against or as a warning sign against any thinkable kind of usage. The resulting dichotomy between technologist fervor and conservationist resistance constitutes a chasm which further swallows up global marine justice. In narrative terms, when it comes to utilizing or exploiting the ocean floor's resources, global marine justice remains close to a “nonstory” (Berg and Hukkinen, 2011:153); there is hardly any positive rhetorical form which would show how it would work, what it would aim at, and what the ocean itself would look like if it took place. We wonder why this is, what it means for the political dynamics of the DSM debate, and what it might teach us regarding the articulation and communication of marine justice.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 explains how this study is guided by our approach to narrative analysis as well as by our specific interest in – and assumptions about – sustainability discourses. Section 3 discusses a number of specific semantic characteristics that determine the “sound” of the discourse on DSM. Section 4 presents the core of our empirical work on structural features of the entire discourse by reflecting findings from an analysis of a series of short, self-contained narrative sequences. Section 5 continues this reflection by discussing the ways by which arguments for and against DSM emerge, how these arguments relate to the structural properties, and ultimately what degree of narrative potency the authors are able to achieve. Section 6 draws on this discussion in order to reflect on pitfalls for critical narratives. The paper is concluded by reflections on how a more successful DSM-critical narrative could be structured in the future.

There is an important body of psycholinguistic literature about the effects of transportation, i.e., the narrative “placing” of the reader into the story, and identification that fictional stories exert on readers (Green and Brock, 2000; Appel et al., 2015). The pronounced “experientiality of an anthropomorphic nature” these stories possess (Fludernik, 1996:19) is tied to the portrayal of characters and their actions (Cohen and Tal-Or, 2017) and can be detected at a level of individual sentences or paragraphs as well (Greimas, 1986:173, 185). The latter point gives us the right to assume that also nonfictional texts, and, for that matter, any nonfictional discourse beyond and across individual utterances and texts, will be composed of (or permeated by) what Algirdas Greimas called “micro-universes” or “small dramas” (Greimas, 1986:128) and what we denominate micronarratives. Each of these building blocks will, as Kenneth Burke famously put it, answer five essential questions, namely which actor (agent) performs which act, where (scene), how (agency), and with which purpose – a “pentadic” structure that mirrors what discourse performs at its macrolevel (Burke, 1969). In the study leading up to this paper, we cast a net of pentads over selected text corpora, assuming that the more complete these micronarratives are and the more their individual positions (e.g., purposes or scenes) amount to a coherent picture, the greater a “narrativity” the respective discourse will possess, i.e., the more it will be able to pull a reader or listener in and keep their attention, as a necessary condition for persuading them.

The importance of narrativity, understood in this manner, for effective political rhetoric is evident, especially so in an age of digitally divulged information where readers jump from text to text and have a hard time maintaining attentional focus (Baron, 2017:16–18). For sustainability rhetoric this is all the more important, as most sustainability issues – apart from climate change and the fight against poverty – still have a hard time making the cut in the daily struggle for public attention (Barkemeyer et al., 2018). In nonfictional texts, it cannot be expected from nonexpert readers that they for instance infer the intent of described actions from the wider context if this context is in principle unfamiliar to them; rather, it needs to be made transparent and tangible as often as possible. Increasing narrativity in the above-defined sense could make a difference here, especially when topics, like the one we deal with in this paper, appear to be temporally and/or spatially remote (Rivera and Nanz, 2018).

When analyzing discourse as a system of utterances that is stabilized beyond individual texts and speakers, and that is at least partially decoupled from their intentions and capacities (Jung, 2011), we ought to assume that narrativity as a structural feature is not indefinitely susceptible to individual manipulation. In the case of micronarratives, i.e., the pentadic cells that assign motives to acts and agents, a central correlation is to be hypothesized between their respective purposes and the overall motivational structure the discourse impairs – which, in analogy to that of a person, is nothing other than its value base (Barnea and Schwartz, 1998:19–22; Schwartz, 1994). It is our hypothesis, which we are testing and differentiating in different fields of sustainability-related content analysis, that sustainability discourse(s) is (are) structured through three sometimes converging, sometimes competing value clusters, which correspond to three (out of four) main fields in Schwartz's theory of universal human values, namely conservation and stability, innovation, and justice. There is no room in this paper to develop and defend this hypothesis (for further reading, see Rivera and Kallenbach, 2020); it must suffice to say at this point that there is ample support for it to be found not only in the aforementioned general value theory but also in the specific political history of sustainable development over the last 50 years (Dresner, 2008:21–68) and in empirical argumentative analyses (Schwegler, 2018). Our own findings in this paper add further plausibility to this assumption. Before presenting them, we briefly explain how we got to them through narrative analysis and thus their scope and limitations.

As contributors to an extensive scoping study on the current applicability and possible reinterpretation of the common heritage of mankind (CHM) principle (Christiansen et al., 2019), we were asked to analyze the discourse “on DSM” – not in terms of its argumentative cogency but in terms of its narrative potential and shortcomings, which we approached in the above-stated terms. This set the course in a way that predetermined some of our results. We selected documents whose main topic was not (only) the high seas themselves but DSM specifically. Not surprisingly, the discourse proved to be structured by the antagonism between DSM propagators and detractors, with a third group of texts at least attempting to avoid partisanship. Our results, therefore, could in theory be relativized by pointing out that, by sampling this corpus, we failed to appreciate a broader debate on the future of the deep sea beyond national jurisdiction in general and not centered on DSM. We would argue, however, that such a debate hardly exists anywhere else.

DSM itself is still a predominantly expert-driven topic that fails to mobilize wider publics. Just to give an impression, while Google delivers around 4.39 million results for “renewable energies”, “deep-seabed mining” is found 471 000 times only (as of 21 October 2019). Although we included a media section in our sample – especially because of our interest in storytelling, which media reports are forced to perform by rules of their genre – we therefore contented ourselves with a volume of text for this section that is smaller than those of the other speaker groups we took into account. We assessed 39 publicly available contributions from 2010 to 2018 (in English and in German), sampled in roughly equal parts from all the relevant speaker groups, i.e., academia, civil society, politics, business, and the media. “Equal” here refers to the number of documents, not to their volume, meaning we had to weigh all quantitative elements of our analysis accordingly or translate them into percentages within groups. A further criterion for the selection of this sample, which claims no statistical representativeness whatsoever but nonetheless eludes arbitrariness (Elo et al., 2014), was the equal representation of voices from advocates and opponents as well as of mediating, objective, or neutral voices. Looking at the intersection of proponent and opponent sets with the speaker groups, we find business and politics overwhelmingly in the pro camp and civil society exclusively in the contra fraction, while academia is partly neutral and partly critical and media articles are to be found in all three camps.

Quantitative features in our method triangulation comprise traditional word counts, to get a hold on overall semantics, and distributions of certain subcodes within pentads, e.g., on the types of purposes (or the lack of any purpose), by which we inferred the value structure of the text corpus. We did not include any other more elaborated lexicometric method, as we did not want to register topics or style but rather the structure of micronarratives. The main work, therefore, was purely qualitative, namely the establishment and description of these micronarratives, or pentads, themselves. Deciding upon how many pentads to establish and analyze in each text ultimately came down to assessing our own working capacities and to a sense of proportionality. Over the entire corpus consisting of 39 documents (and about 215 000 words), we cast a net of 240 pentads, i.e., about six pentads per text (or one per 900 words), but we let that average vary according to the length of each document, coding very short media articles for instance with only 2 and lengthy business reports with occasionally up to 10 pentads. In order to control whether and how micronarratives truly were conducive to the overall discourse's value structure, we applied a distinction between “ought” stories, which directly express the state of affairs deemed desirable by the author, and “is” stories, which claim to describe reality. This distinction had to be coded as well.

The about 1550 pentadic codings that resulted from this operation, and which reflect the constellations of action the discourse invokes and “narrates”, were complemented by more than 300 thematic codes, by which, in some, we traced direct mentions of the CHM principle and related value references separately from the pentads to increase the validity of our results. Others were used to register metaphors that we presumed could harbor paradigmatic content.

The very first glance at the corpus's semantics reveals a seemingly trivial, but on second thought striking, feature: there is no activity which could even remotely compete with “mining”. Considering three-word combinations that include a verb or active noun and that were mentioned more than 10 times throughout the corpus, mentions of mining amount to more than triple of all their closest competitors together. These competitors are of a heterogeneous kind; environmentalist notions (e.g., “preserving deep sea”) are paired with those of exploration (“marine scientific research”), and it is noteworthy that some of them, like “environmental impact assessment” are conceptually dependent on the economic activity in question.

This does not imply that mining is affirmed throughout – as said before, the discourse is structured as a debate pro and contra mining – but it indicates that there is hardly an alternative notion of what to do with (or in) the deep sea instead. The semantic centrality of exploitative activities pervades all groups of documents and speakers. As a single verb as well, “mining” beats all other competitors by quite a margin, with the paradoxical exception of business documents which, in defending exploration, make a point of emphasizing that “analyzing” the state of affairs is crucial. Opponents of DSM are often just that – opponents; they spend a lot of time refuting DSM argumentatively instead of setting forth an independent vision or story. One may say that they make the most classic mistake of political communication by involuntarily reaffirming the adversary's frame (Lakoff, 2008).

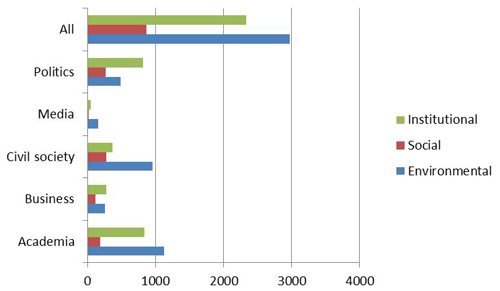

Besides this preeminence of an exploitation-oriented vocabulary, we can see how aspects of environmental concern, social justice, and institutional pragmatism shape the debate semantically and how they are accentuated differently by different groups of speakers. At first glance, an environmental framing prevails. Right after the words “deep”, “sea”, and “mining”, it is the words with the root “environment” that by far lead any conventional word count, even beyond the selected dictionary presented in Fig. 1. (In the selected dictionary, besides the lexical “environment” and “Umwelt” family, we included words such as “nature”, “protection”, and “ecology”.) This semantics is of course even more pronounced among DSM opponents, but the other camps observe it too, which means that the former have at least succeeded in making the mitigation of environmental impacts of mining activities an issue that everybody in the debate has to address. Yet this environmental concern, juxtaposed to the powerful pull of “mining”, gives rise to an institutionalist cadence as well, caused by terms like “regulation”, “implementing”, “legal”, “annex”, and the like. This semantics surrounds the environmentalist semantics and occasionally even overwhelms it, thus confirming an earlier finding that ocean discourse is anchored to the central notion of “management” (Kronfeld-Goharani, 2015:314), a word which is very prominent in our corpus as well. It is not surprising that this institutionalist sound is louder in documents issued by institutional political actors and considerably weaker in media articles and civil society publications (Fig. 1). Yet, even NGO statements employ this politicotechnical language to a degree that might become problematic for narrativity, an aspect which we will elaborate on further in Sect. 4.

What clearly takes the back seat, though, is any more immediately social, let alone justice-related, semantics. In analogy to the environmental and institutional branches of our dictionary, we had built its social section out of words that we considered essential for characterizing the semantic area (deductive component) and/or those that caught our eye in the overall word count (inductive component). As a result, each branch of the dictionary was comprised of 21 words and lexical roots. While this, in a hypothetical “baseline” discourse, would lead to a more or less even three-thirds distribution, in reality the social vocabulary accounts for barely a seventh of all the relevant sustainability notions. This is less than is accounted for by the word “environment” and its lexical relatives alone. Words like “conflict”, “poverty”, or “inequality”, apart from appearing in only a handful of documents at all, are mentioned so seldom they almost seem inexistent. (And not a single micronarrative about desirable acts that we coded – “ought stories” – even mentions them as something that ought to be addressed.) More prominence is attributed to notions like “sharing” and “distribution” (e.g., of revenues from mining), but even they pale in comparison with words like “biodiversity” or “ecosystem”. This relative weakness compared to an environmental vocabulary is even more pronounced in the documents that criticize DSM than in those that defend it, indicating that the economic core of the common-heritage idea (sharing revenues) is, if at all, mobilized by those in favor of mining. Those who try to communicate the debate and its central axis of conflict – whether to mine or not to mine – vis-à-vis a wider public, hardly make use of any social vocabulary at all.

This justice-related deafness especially among those who are either the most inclined to criticize DSM and mobilize resistance to it (civil society) or the most interested in making it a good story (the media) seems to suggest that, for some reason, the critics cannot construct a strong relation between social matters and conflicts, on the one hand, and mining prospects or the workings of the ISA, on the other. To elucidate this hypothesis, we need to dive more deeply into the discourse and its narrative structures.

To begin a systematic reflection of prevalent narrative structures, we first take a look at the scenes in which stories about DSM usually take place. The current discourse refers to two, contextually extremely different, places of action. On the one hand, the audience is sent down to the bottom of the deep sea. We find ourselves in a space that is in many respects alien and far removed from human civilization. Down here, several kilometers below sea level, the pressure is extremely high and eternal darkness reigns. To a nonspecialist audience, both the scenery's topography and life-forms seem strange and bizarre. Due to incomplete or unreliable information, many contextual circumstances quite literally stay in the dark. The “stage design” remains unfinished, resulting in a great deal of leeway – and also the necessity – to complete the fragmentary setting with subjective, oftentimes quite diverging images. In making this observation, we are reminded of Philip Steinberg's claim that the four-dimensional nature of the oceans – which includes time, width, breadth, and also depth – renders any human encounter with marine environments “distanced and partial” (Steinberg, 2013:156). The deep seabed is arguably the marine environment to which these characteristics apply most strongly.

The images used to fill the knowledge gaps serve as an important reference for lines of argument in favor of or against DSM. Advocates of DSM often reinforce the notion of the seabed as either a largely inanimate desert where nothing and nobody will suffer any damage or a marine ecosystem that is resilient to disturbances caused by the mining of minerals. Opponents of DSM tend to depict the seabed as a fragile biodiversity hub that is of significance for the entire planetary system. The gaps in knowledge regarding the marine environment's vital dynamics are understood as reasons for a hesitant and cautious approach to the precious, fragile scene. This image enables the opponents' ecocentric narrative of necessities.

The second major scene of action is the political–administrative process of licensing and regulating DSM at the ISA in Jamaica. This is the scene favored by narrators in civil society, academia, and politics itself (while business documents and media articles tend to favor the seafloor). The activities and the place that will be negotiated here, i.e., the mining of minerals deep down on the ocean floor, could not seem more distant. Unlike the abovementioned deep-sea context, the ISA scene will probably evoke assembly halls, negotiation rooms, and offices in which bureaucrats, political representatives, and experts negotiate contracts and all sorts of other legal documents. At the ISA, unlike in the example above, reference is therefore made to a purely institutional space, which, as will be explained below, remains strangely impersonal and buried beneath a hollow institutional vocabulary and rhetoric.

Despite this stark contextual contrast, which clearly complicates a narrative connection between the two scenes, there is also an interesting parallel in the way the seabed and the political process are depicted. Both are characterized by a high degree of abstraction and, as a result of limited information, opaqueness. We shall return to this parallel below as one of the central problems, especially in the context of the discourse critical of DSM. At this point, it is worth pointing out that the institutional space of the political process at the ISA tends to be even less illustrative than the context of the seabed. An explanation for these observations is provided by an in-depth look at the four remaining pentadic structural elements: agent, act, agency, and purpose.

4.1 Who intends to do what on the seafloor?

In the deep-sea scene, the single most often encountered protagonist (agent) is mining itself. There is never any talk of actually-existing individuals, and only in a few exceptions are concrete companies mentioned. The latter happens in connection with accounts of planned mining in the territorial coastal waters of Papua New Guinea, a case which, as we shall discuss later, does not match the context of DSM in international waters. Regardless of whether we are in international waters or in the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of a state, the mining sector operates (acts) by exploring, testing, and exploiting. It does this, as expected, through the use of technologies (agency), i.e., by using sensors to explore resource stocks or by using machines to clear the seabed. The objective (purpose) of these activities is often described explicitly as the extraction of specific mineral resources such as manganese. Descriptions of the activity of DSM produce equally complete and coherent pentads, thereby achieving a high degree of narrativity. This effect arises regardless of whether the narrator identifies themselves as an advocate, an opponent, or neutral. In other words, irrespective of whether DSM is presented in a positive light or as destructive, the narrativity of the account always remains at an unchanged high.

In a few cases, the role of the agent is also played by marine science. Compared to its important narrator voice in the discourse through its numerous publications, however, science appears as an actor rather seldom. Where it does, hardly any concrete persons are ever described. Individual scientists regularly appear as authors of one or the other opinions, especially in the media. In narratives about what science does in the deep sea, however, the actor science generally remains abstract, impersonal, and characterless.

Scientific activities (acts) involve, as expected, the exploration and cataloguing of the deep sea's living and inanimate environment. Furthermore, science is concerned with making reliable statements about possible effects of DSM on this animate and inanimate environment. The means (agency) by which these activities are carried out usually remain unclear. Here is an interesting contrast to the means of DSM, which – despite their high-tech nature – are usually catchy and self-evident. Moreover, the activities of science, considered in isolation, are in many respects similar, if not synonymous, with the exploration activities carried out by the mining industry. This leads to the impression, sometimes quite rightly, that science is ultimately acting as a mere vehicle for those political and economic actors who want DSM to become a reality. For example, information on the local availability and quality of deep-sea mineral resources ultimately comes from scientists. This impression is further reinforced by the fact that in many cases science appears to be acting without any concrete objective at all. Science simply does what it does, yet without necessarily convincing us that additional knowledge is a goal that possesses validity beyond the emergence of DSM. Knowledge in itself is seldom the purpose of micronarratives in the overall discourse (about 5 % of the pentads refer to it), but it never is when these narratives unfold on the ocean floor. Research activities of marine science therefore appear to occur primarily in connection with or in response to DSM. Absent remains any hero scientist à la Jacques Cousteau or Thor Heyerdahl, who, equipped with exceptional intelligence, bravery, and noble objectives, would bring us the wonders of nature all the way from the depths of the sea into our living rooms. While contemporary oceanographers such as Cindy Lee Van Dover have in fact been hailed as deep-sea pioneers elsewhere, they are sought in vain in the context of the DSM debate. This contributes to the defensive, rather than heroic, shape of the environmentalist standpoint.

In addition to the mining sector and the occasionally occurring marine science, Nature itself also appears from time to time – and in different forms – as an actor on the seabed. This happens, for example, when ecosystem dynamics are described. Nature's deeds, however, follow no purpose; epistemically and rhetorically, they are conceived as motion, not action (Burke, 1969:10). Ecosystem services, indispensable to human survival, are not the result of good will but rather a purely coincidental product of a dispassionate agent. This applies in particular to situations in which natural processes such as the sink function of seawater assume the role of agent. They are simply not characters or protagonists we can relate to in the sense we established in Sect. 2. Yet the narrative potential of seabed's life-forms as an archetypal victim is limited as well. The problem here is distance due to otherness. Deep-sea creatures are not only completely unknown and alien to the majority of the human audience but also exclusively lower animal species, which offer comparatively little scope for identification. Unlike some higher animals, deep-sea life-forms are hard to humanize. “Microscopic critters on the seafloor”, as one author from the science community denotes them, are a much less convincing cast than TV's usual suspects, i.e., dogs, dolphins, and horses. As animals are generally valued through cultural coding (see e.g., Birke, 1994; Hastedt, 2011), the audience will react with less empathy to the fate of these remote life-forms.

4.2 Who is doing what at the International Seabed Authority?

In the scene of the political process at the ISA, we encounter quite different actors from those in the depths of the ocean. Here, nation-states, governments, international authorities – especially the ISA itself – and public–private partnerships dominate the course of events. Human individuals are absent from the stage here as well. The actors remain, once again, largely abstract and impersonal. This is reinforced by the fact that, while the mining sector literally carries its agenda in its name, it is hard to tell prima facie what “Germany”, “Kiribati” or the “ISA” might stand for. For an audience without a detailed knowledge of the process, i.e., the great majority of the general public, the actors involved remain faceless.

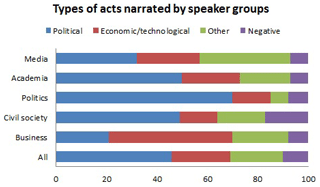

Equally vague are descriptions of what is done here (act). As dominating acts we find activities like regulating, lawmaking, governing, or management (see Fig. 2). But what purpose do all those acts, explained in great detail in academic and policy documents and referred to constantly in all other speaker groups as well, ultimately serve? At the level of micronarratives, this question receives no answer. Unlike most acts from the field of mining, which are mostly self-explanatory – think of the activity of digging, for example – these political acts generally require further explanation to generate a narrative momentum. To do so would involve elaborating on both the object and the ultimate purpose of these political acts. Stories about regulation would need to clarify what exactly is to be regulated and why. In lieu of such critical information, political acts mostly remain empty and meaningless. We assigned the code “Purpose: missing” to paragraphs were the purpose of a described activity was neither made explicit in the coded passage nor inferable from its immediate context. This does not mean that the activities could not be attributed a purpose when thinking harder about them or when deducing the intent from the text as a whole but rather that this purpose remained opaque at the microlevel of the respective sequence or the paragraph. As stated in Sect. 2, such implicitness, if overly frequent, decreases narrativity and therefore resonance with the distracted or not yet involved, i.e., nonexpert, reader. Such relative purposelessness runs through the entire DSM discourse (91 out of 240 pentads) and particularly through the part that deals with the ISA, where almost half of the micronarratives are coded accordingly (20 out of 55). The result of this mechanical rhetoric is an impression of pointlessness, which in turn renders engagement with the texts unlikely.

The means (agency) by which those political acts are pursued are either also depicted in a superficial and opaque way or not mentioned at all. There is no open argument, haggling, threatening, or deceiving as one might expect in a drama or a tragedy (White, 1973:94–95) about the distribution of a huge stock of natural riches. Nor does anyone use their power or other political means to push their agenda or to sideline a competitor. An exception to the rule is historical accounts of the establishment of UNCLOS in the 1960s, which tell us about an open political confrontation between the industrialized global north and the developing countries. The ISA process of the present day, however, appears to be free of any such animosities or disagreement. There appears to be nobody of the likes of a Daniel Plainview2 – the protagonist from the movie There Will Be Blood – whose deeply troubling actions could arouse outrage and possibly opposition to the injustices in the politics and practices of DSM.

Yet not only are the bad guys missing in the political process but also heroes are again undetectable. This circumstance occurs especially in narratives about environmental protection, the enforcement of rights and obligations, or the monitoring and control of the DSM community. Such ought stories represent almost a third of all of the stories we analyzed. Yet, where a good narrative would require a hero or a heroine, virtually all of the actors remain – once again – completely abstract, in the sense of a global “we”, people, or the public. But who exactly must take action here? In other cases on the matter, the associated pentads contain no agent whatsoever, leaving the audience clueless about the question of how political demands could become a reality.

Taken together, the ISA process appears to be stripped of its social context – an observation that is in accordance with the earlier-stated predominance of managerial, and the absence of social, semantics. The story we are told is not one about people trying to come to terms about a complex and conflict-laden social problem but rather one about an expert-driven technocracy. This apolitical narrative is taken to extremes whenever the ISA alternately, or simultaneously, represents the scene, the agent, and the agency. Other such cases are pentads in which legal texts such as the UNCLOS or the ISA Mining Code are placed in the role of the agent – legal texts are in fact the fourth-strongest actor group in our pentads. This way, the political process appears as a self-perpetuating machine – a metaphor embraced by a high-ranking civil servant when he praises the ISA as “international machinery” that is “functioning well”. We know this discursive effect from conventional development policies, where development projects are portrayed as exclusively technical–administrative acts, which conceals their inherent potential for social conflict (see e.g., Ferguson, 1994; Li, 2007).

The narrative structures of the current DSM discourse that we described are both an expression of and a demarcation for the arguments in favor of and against DSM. The opponents' arguments have in part been described above: the deep sea and the seabed represent unique and valuable habitats that would be immoral, irrational, and dangerous to destroy. This is reminiscent of the criticism of excessive deforestation in rainforest areas: an appeal partly to the intrinsic value of biodiversity and partly to the functional importance of global ecosystem services. To endanger the former through DSM could destroy values that are hitherto unaccounted for; to endanger the latter could amount to a disturbance of planetary systems beyond the deep sea itself and thus cause harm even to humans. However, while the risks of an irreversible destruction run through the majority of the opponents' texts, their actual argumentative starting point is mostly a much less aggressive one: we don't know enough. The DSM opponents' central narrative moment is thus a lack of certainty, which translates into the demand for a precautionary approach. In comparison to DSM advocates, who with reference to huge resource deposits persuade us that they know what they are talking about, this clearly represents a narrative – not argumentative – weakness.

The opponents' cautious position implies the need for at least postponing DSM until more factual certainty is achieved; it is convincing as long as one adheres to the precautionary principle. However, it does not foreclose DSM indefinitely and peremptorily. In narrative terms, this position evokes a feeling of delay and increases the need to tell what one should do with the deep sea instead. To simply leave it alone may appear tantamount to a simple do-nothing approach and thus to a nonstory. The act of protection itself, on the other hand, is difficult to stylize into a true melodrama. In contrast to whaling, protecting the deep sea is hard to picture as an active, heroic fight between a polarized cast of protectors and exploiters, infused with moral gravity (Schwarze, 2006:245). On the ocean floor, nobody (agent) should do anything (act). Moreover, and again with a view to the overall discourse, the opponents are forced to produce a narrative of their own on how to deal with the reasons cited as justifications for DSM, e.g., a steadily increasing need for resources. The mere rejection of mining has not yet invalidated these reasons. The opponents see themselves in need of convincing counternarratives if they want to live up to their role as narrators.

The drivers of the discourse, DSM advocates, locate the agent (and/or beneficiary) of DSM either in an entirely unspecified humanity or in a nation that benefits from an improved location-related economic competitiveness. In the former case, they at least rhetorically connect to the common-heritage vision of the likes of Elisabeth Mann-Borgese or Arvid Pardo; they have however given up part of its promise and redefined its necessity. Costs and benefits of DSM projects tend to be compared with those of traditional terrestrial mining and the availability of land-based resource stocks. Against this background, DSM is no longer primarily discussed as a source of novel wealth but rather as a potential means to securing current standards of production. Its proponents argue that using deep-water resources for economic development is inevitable if humanity is to respond no longer to a global concern for peace and political cooperation but rather to dwindling land-based resources and to urbanization, population growth, and modernization processes that increase the global demand for metals and rare-earth elements. DSM is presented as a mandatory prerequisite for sustainable development and associated with a green and modern image that connects both to an audience of potential private and governmental investors and to a concerned global public. This shift away from narratives of promise to narratives of necessity, including the invocation of minimized harm and a lesser evil, resembles not only the shift in corporate rhetoric observed by Ryan Katz-Rosene (2017) regarding the extraction of oil from sandstone but also, to a certain degree, frames invoked by advocates of climate engineering (Schäfer and Low, 2018:302–304).

The argument regarding the lack of alternatives to DSM appears particularly persuasive when the metals of the deep sea are associated with their use in concrete everyday technologies such as mobile phones, flat screens, solar cells, car batteries, or wind turbines. Even a critical audience might be tempted to agree the following: we simply need that stuff! Moreover, the reference to the secured supply of such everyday technologies carries the promise of everyone benefitting (i.e., at least the consumer society in the global north). The promise that we can continue as before is evoked, making us forget that consumers will pay a price for these technologies and also that the profits from this trade are not necessarily distributed in the sense of global and intergenerational justice. The mining industry appears to work on behalf of humanity as a whole. To the bona fide reader, this narrative of secure access to important technologies may therefore seem like the CHM becoming an actual reality.

This globalist green modernization narrative, which can be reconstructed out of many of the pentads especially in business documents, is complemented by a second line of reasoning, which is even more remote from international-justice concerns than the first. It centers on location-related economic competitiveness. Here, the development of a modern green industry is explicitly discussed in light of national and sectoral interests. Highly contrary to the original CHM spirit, the money to be made and the jobs to be created are presented as a domestic opportunity that should not be left to international competitors. This competitiveness narrative appeals both to the hope for economic boom and to fears of losing touch and coming under political and economic pressure from the outside. For instance, warnings are repeatedly voiced against the German industry being left behind by international competitors, especially by an overly powerful China. Here the industry does not appear to be guided by self-interest either but again to be acting in the interest of a collective. What is interesting about this location argument is that it actually implies a certain variant of political conflict. Prominent DSM metaphors such as scramble for resources or gold rush evoke an international scene in which the right of the strongest prevails over solidarity. This conflict, however, takes place exclusively between the economies or the governments of entire nation-states and is therefore largely detached from the reader's world. Unlike in the context of other narratives – such as that of an ecocentrically legitimized environmental protection of the deep sea – one can nevertheless sense real human suffering on the distant horizon, i.e., unemployment. The location argument first causes a partisan audience to identify with it, in the sense of a national feeling of “we”, and then, in a further step, to approve a national commitment. While the proponents are fundamentally interested in painting DSM as conflict-free – which we have shown they also do very successfully – they at the same time know how to make narrative use of a conflict.

When fleshing out these ideas, DSM proponents especially in the private sector can rely on a gamut of economic and/or technological acts, from “changing mining industry for the better” to “developing resources” and from “supplying generators” to “building modern devices”. Figure 2 shows the dominance of these types of acts in their discourse – as well as the fact that their opponents cannot elude these acts either. This occurs both when the opponents describe what miners want to do matter-of-factly (e.g., “exploit”) and when they set out to criticize these activities as dangerous (mining as “wiping out pristine habitats”, for example). This critique also results in what we call negative acts and what is an indirect way of affirming one's own purposes. Narratively, it results in sentences that are nonstories, though, as for instance when the ISA is accused of “failing to represent the common interest” or when DSM-friendly scientists are said to “not use the appropriate data”.

Justice, on the other hand, does not come through particularly clearly in any of the discourse's segments. When a DSM license holder claims, for example, that their activities will mean “no depletion of Kiribati's natural resources, zero impact on Kiribati's environment and fish stocks, and no cause for land use conflicts”, they smuggle a conflict avoidance motive into a negatively articulated set of purposes so indirectly that one will have to deliberately pause and think in order to notice that there is something implied about justice here; the sentence is far clearer about environmental and social stability than about justice sensu stricto. Examples like this, where you have to squint in order to notice justice-related motives, are the rule rather than the exception.

The same applies to explicit, generic references to lawfulness, such as when an NGO demands from the ISA that they “must prioritize conservation of the deep sea, the rights of coastal communities and the rights of humankind as a whole”. Here again, the “rights of coastal communities”, while forming the most concrete clause of the sentence, are not easy to picture: how exactly would they be affected by activities in the deep sea in areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction? Scientific considerations about the shape of potential conflicts with the coast, e.g., about sediment discharged in the course of seabed mining traveling to coastal state waters, are very marginal in the discourse and not mounting up to a palpable story yet, nor are possible conflicts of DSM with navigation, with the exploitation of genetic resources, or – most importantly – with fisheries. Although it is possible that conflicts with fisheries could occur, especially at shallower parts of mid-ocean ridges and seamounts (Christiansen et al., 2019:55), DSM critics do not yet fully tap into experiences associated with resource and other conflicts and ensuing injustice (a framing used successfully for instance by the food-or-fuel debate in the late 2000s).

Mining minerals from the seafloor is a perfect story in terms of simplicity, vividness, and a romantic plot (White, 1973). As a result, all other narratives of the discourse must measure themselves against it. Our study demonstrates that arguments that are critical of DSM face major challenges in terms of narrativity. This is felt through a wide distribution of incomplete pentads. Context (scene) and means (agency) and especially actional intent (purpose) are frequently missing in micronarratives and even more frequently when one looks at the opponents' side of the debate. This applies to descriptions of the remote and unexplored seafloor but even more so to actions that occur in the context of the ongoing ISA process.

For proponents of DSM, the distance between the audience and the location of the event and the lack of clarity on what is happening there represent a clear narrative advantage. The spatial distance to the seabed in international waters creates a feeling of relative safety. Mining's access to these distant resources appears as both impressive and harmless, i.e., without any immediate personal consequences for the audience. Telling the story accordingly runs little risk of evoking a not-in-my-backyard reaction, a commonly encountered obstacle in the context of green tech innovations (Schwenkenbecher, 2017). The sparseness in imagery will hamper a reader's immersion (Green and Brock, 2000:718–719) and allow them to shed any sense of personal responsibility. Regarding the political scene, abstraction goes even further. The political process remains so opaque, and so devoid of agents, that many readers may be led to conclude that the politics of DSM should stay as it is, i.e., reserved for experts.

For DSM opponents, the detachment and the lack of clarity are for the most part a clear disadvantage. Without human or animal actors and far away from the audience's living environment, it is difficult to create a space for identification and to arouse the emotions, empathy, and interest that would be necessary to condemn DSM once and for all. An interesting exception is the partial discourse on mining in the exclusive economic zones of individual states such as Papua New Guinea. Here, the narrative of the DSM opponents works much better. Not only do the species and ecosystems there seem closer to us (and therefore more valuable), but most importantly, we are confronted with concrete human victims. As these victims' resistance harbors the potential for heroic stories as well, rhetorical chances for success might increase (Shanahan et al., 2011:553). This being said, DSM in the EEZs can only be used to a limited extent as a template for a better critical narrative. Projects such as the notorious Solwara 1 are by definition not part of the CHM and outside the ISA's responsibility. If civil society succeeds in presenting individual mining companies or governments in the EEZ as villains and the local coastal inhabitants alternately as heroes and/or victims then they are on their way to telling a good contra-DSM story. However, the type of deep-seabed mining discussed in the frame of the ISA is still far from being overcome in a narrative way, as it will eventually occur thousands of miles from the coasts and at depths of several thousands of meters where a story on the presence of immediate harm to humans appears much less convincing.

Today, the values of protection, innovation, peace, and justice that dominated the original discussions in the 1960s remain almost completely hidden behind the technocratic facade of the ISA process. In concluding this discussion, we ought to ask whether and how the narrative potential in those value references could eventually be “mined” more successfully. A first tentative answer would imply that, for DSM opponents to come up with a competitive protection-related narrative of necessity, they would require a much more pronounced description of the negative ecological consequences of DSM, especially those that go beyond the local context of the seafloor and that succeed in describing concrete implications for human health and livelihoods. In order to strike a note with the audience, narratives on environmental protection would need to be clad in the anthropocentric appearance of conventional narratives – as much as one might lament this necessity (Ghosh, 2016). What we are observing here in the context of DSM applies, albeit to a lesser extent, to debates on marine justice in general. Martin et al. (2019) argue that established approaches to environmental justice – with their roots in terrestrial, place-based pollution – find themselves challenged by marine socioecological system dynamics that stretch and dilute over vast distances. If this holds true for classical matters of pollution and fish stocks, it becomes even more pronounced in the case of geochemical connections and disturbances that become visible only through complex scientific models. Yet the rise of climate justice as a narrative, or at least as a slogan, that is able to mobilize wider publics seems to show that the challenge can be met.

A second, complementary approach would entail a stronger revaluation of the deep sea's animate environment. Both strategies would allow the telling of the story of the environment's destruction and of the battle fought by its protectors as a melodrama that mobilizes empathic publics (Kinsella et al., 2008). However, as we have argued earlier, attempts to paint underwater robots and mining devices as cruel and life-threatening often fall flat in the face of a remote and somber deep sea which is not easily portrayed as an underwater rainforest.

Why not, then, talk more about justice? There is an immense potential for social conflict that the current discourse successfully conceals. DSM opponents already appeal to it, argumentatively, by referring to the procedural dimension of matters. Yet their claims for more transparency, responsibility, and inclusion fail to translate into a good story because of the abstract, legalist rhetoric in which they are embedded. A reinterpretation of the ISA process would have to turn away from the hyperinstitutionalist semantics towards stories narrating the deeds, intents, and entanglements of concrete political actors. A critical narrative about DSM would require a minimization of distance by way of a rigorous repolitization, narrating the politics behind the policies. A corresponding “real-world geography of flows, encounters and power relations” (Walker, 2009:627) would need to rebuild the political space in narrative terms. Yet, as long as neither human action nor human destinies become recognizable in the context of DSM, the discourse also remains cut off from its inherent justice-related core. The principle of the common heritage of mankind, which since the 1960s has been the foundation for this justice-related core, thus remains reduced to a permanent marginal note of which, if at all, only the ISA's technocrats will take notice. This narrative trap seems to mirror the conceptual one that David Pellow reproaches the environmental justice movement for: to mistakenly believe that recognition by state authorities will result in policy change (Pellow, 2018:12). In the case of DSM, however, the trap seems to be not so much the authoritarian reliance on the nation-state but rather overleaping the said state in favor of the supranational machinery. Investing this machinery with human faces and sensitizing national publics to the actions and intentions of their representatives are necessary conditions for the reappropriation of marine justice in DSM matters.

Yet, if both the justice-related and the protection-related cores of the DSM theme should continue to prove infertile, then leaving the DSM context altogether appears to be the way forward. An innovation narrative would be required that is even more persuasive than the story of seabed mining and makes the latter appear unnecessary or even better, boring. Argumentatively – but not narratively – opponents already have one such alternative at their command: the global circular economy. Its narrative could counter the promised deep-sea gold rush with an even more promising gold rush on the cities. Are the metals we need not already littering our streets? All we have to do is pick them up! It would be a narrative much closer to people's lifeworld and with more inclusionary potential. On our way to getting there, it may be worth recalling the optimistic initial discourse on innovations in the field of solar energy which, beyond the creation of an alternative to fossil energies, also promised a fundamental energetic and thus political decentralization and democratization of access to energy. In the context of the associated energy democracy–justice discourse, social–ecological innovation is framed not only as a narrative of necessity but also as an appealing narrative of promise (see e.g., Angarita Horowitz et al., 2017; Burke and Stephens, 2017; Heffron and McCauley, 2017).

Public access to our sample or data set cannot be realized as our sample is composed of newspaper, magazine, and online articles, each of which are protected by individual publishing rights that prohibit or constrain the use or reproduction of these articles by third parties.

Both authors contributed equally to the conceptualization of the paper as well as to designing its overall structure. Equal contributions were further made with regard to the design of the study's empirical research. OS's contributions further include the lead in compiling and analyzing the document sample as well as in writing the original and the revised draft manuscripts. MR's contributions include the lead in writing the original methodology section as well as substantial and continued effort in editing and reviewing the manuscript and driving the research process in general.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We wish to express our gratitude to our editors for their continued support and their valuable comments. Further thanks go to our anonymous reviewers and the participants of the international workshop, “Narratives and practices of environmental justice”, 2019, in Kiel, where an early version of the paper was presented. Last but not least, we wish to thank the members of our research group, Narratives and Images of Sustainability, at IASS Potsdam for our joint and novel approach to narrative analysis as well as Sabine Christiansen, also IASS, for involving us in the debate on deep-seabed mining.

This paper was edited by Anna Lena Bercht and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Angarita Horowitz, D., Baker, I., Benander, L., Cervas, S., Delman, B., Giancatarino, A., Huang, V. Y., Johnson, D., Fairchild, D., and Weinrub, A.: Energy Democracy: Advancing Equity in Clean Energy Solutions, Island Press, Washington, D.C., 2017.

Appel, M., Gnambs, T., Richter, T., and Green, M. C.: The transportation scale – short form (TS–SF), Media Psychol., 18, 243–266, https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2014.987400, 2015.

Barkemeyer, R., Givry, P., and Figge, F.: Trends and patterns in sustainability-related media coverage: A classification of issue-level attention, Environ. Plan. C, 36, 937–962, https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654417732337, 2018.

Barnea, M. F. and Schwartz, S. H.: Values and voting, Polit. Psychol., 19, 17–40, https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00090, 1998.

Baron, N. S.: Reading in a digital age, Phi Delta Kappan, 99, 15–20, https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721717734184, 2017.

Berg, A. and Hukkinen, J. I.: The paradox of growth critique: Narrative analysis of the Finnish sustainable consumption and production debate, Ecol. Econ., 72, 151–160, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.09.024, 2011.

Birke, L. I. A.: Feminism, Animals, and Science: The Naming of the Shrew, Open University Press, Buckingham, Philadelphia, 1994.

Burke, K.: A Grammar of Motives (California Edition), University of Berkeley Press, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1969.

Burke, M. J. and Stephens, J. C.: Energy democracy: Goals and policy instruments for sociotechnical transitions, Energ. Res. Social Sci., 33, 35–48, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.09.024, 2017.

Christiansen, S., Currie, D., Houghton, K., Müller, A., Rivera, M., Schmidt, O., Taylor, P., and Unger, S.:Towards a contemporary vision for the global seafloor – implementing the common heritage of mankind, Heinrich Böll Foundation, Berlin, 2019.

Cohen, J. and Tal-Or, N.: Antecedents of identification: Character, text, and audiences, in: Narrative Absorption, edited by: Hakemulder, F., Kuijpers, M. M., Tan, E. S., Bálint, K., and Doicaru, M., John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam, Philadelphia, 133–153, 2017.

Dresner, S.: The Principles of Sustainability, Earthscan, London, Sterling, 2008.

Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Kyngäs, H., Pölkki, T., and Utriainen, K.: Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness, SAGE Open, 4, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014522633, 2014.

Ferguson, J.: The Anti-politics Machine: “Development”, Depoliticization, and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1994.

Fludernik, M.: Towards a `Natural Narratology', Routledge, London, New York, 1996.

Ghosh, A.: The Great Derangement. Climate Change and the Unthinkable, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2016.

Green, M. C. and Brock, T. C.: The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives, J. Personal. Social Psychol., 79, 701–721, https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.701, 2000.

Greimas, A. J.: Sémantique structurale. Recherche de méthode, Presses Université de France, Paris, 1986.

Hastedt, S.: Die Wirkungsmacht konstruierter Andersartigkeit: Strukturelle Analogien zwischen Mensch-Tier-Dualismus und Geschlechterbinarität, in: Human-Animal Studies: Über die gesellschaftliche Natur von Mensch-Tier-Verhältnissen, Transcript, Bielefeld, 2011.

Heffron, R. J. and McCauley, D.: The concept of energy justice across the disciplines, Energy Policy, 105, 658–667, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.03.018, 2017.

Jung, M.: Diskurshistorische Analyse – eine linguistische Perspektive, in: Handbuch Sozialwissenschaftliche Diskursanalyse, Band 1: Theorien und Methoden, edited by: Keller, R., Hirseland, A., Schneider, W., and Viehöver, W., VS Verlag, Wiesbaden, 35–59, 2011.

Katz-Rosene, R. M.: From narrative of promise to rhetoric of sustainability: a genealogy of oil sands, Environ. Commun., 11, 401–414, https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2016.1253597, 2017.

Kinsella, W. J., Bsumek, P. K., Check, T., Rai Peterson, T., Schwarze, S., and Walker, G. B.: Narratives, rhetorical genres, and environmental conflict: Responses to Schwarze's “environmental melodrama”, Environ. Commun., 2, 78–109, https://doi.org/10.1080/17524030801980242, 2008.

Kronfeld-Goharani, U.: The discursive constitution of ocean sustainability, Adv. Appl. Sociol., 5, 306–330, https://doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2015.512030, 2015.

Lakoff, G.: The Political Mind. A Cognitive Scientist's Guide to Your Brain and Its Politics, Penguin Books, New York, 2008.

Li, T. M.: The Will to Improve: Governmentality, Development, and the Practice of Politics, Duke University Press, Durham, 2007.

Martin, J. A., Gray, S., Aceves-Bueno, E., Alagona P., Elwell, T. L., Garcia, A., Horton, Z., Lopez-Carr, D., Marter-Kenyon, J., Miller, K. M., Severen, C., Shewry, T., and Twohey, B.: What is marine justice?, J. Environ. Stud. Sci., 9, 234–243, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-019-00545-0, 2019.

Pellow, D.: What is Critical Environmental Justice?, Polity Press, Cambridge, Malden, 2018.

Rivera, M. and Kallenbach, T.: Narrativity and sustainability. Conceptualizing relations between value structure and rhetorical form, in review, 2020.

Rivera, M. and Nanz, P.: Erzählend handeln, vom Handeln erzählen: Fragen an Narrative nachhaltiger Entwicklung, in: Leben im Anthropozän: Christliche Perspektiven für eine Kultur der Nachhaltigkeit, edited by: Heidel, K. and Bertelmann, B., Oekom, Munich, 137–148, 2018

Schäfer, S. and Low, S.: The discursive politics of expertise: What matters for geoengineering research and governance?, in: Work in Progress. Economy and Environment in the Hands of Experts, edited by: Trentmann, F., Sum, A. B., and Rivera, M., Oekom, Munich, 291–312, 2018.

Schlosberg, D.: Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2007.

Schwartz, S. H.: Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values?, J. Social Issu., 50, 19–45, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1994.tb01196.x, 1994.

Schwarze, S.: Environmental melodrama, Quart. J. Speech, 92, 239–261, https://doi.org/10.1080/00335630600938609, 2006.

Schwegler, C.: Nachhaltigkeit in Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Eine diskurslinguistische Untersuchung von Argumentationen und Kommunikationsstrategien, Universität Heidelberg, Heidelberg, https://doi.org/10.11588/heidok.00025511, 2018.

Schwenkenbecher, A.: What is wrong with nimbys? Renewable energy, landscape impacts and incommensurable values, Environ. Valu., 26, 711–732, https://doi.org/10.3197/096327117X15046905490353, 2017.

Shanahan, E. A., Jones, M. D., and McBeth, M. K.: Policy narratives and policy processes, Policy Stud. J., 39, 535–561, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00420.x, 2011.

Steinberg, P.: Of other seas: metaphors and materialities in maritime regions, Atlant. Stud., 10, 156–169, https://doi.org/10.1080/14788810.2013.785192, 2013.

UNCLOS: The Law of the Sea: Official text of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea with annexes and index, 10 December 1982, UN, Doc A/CONF. 62/122, reprinted in 21 I.L.M 1261, UN Sales No. E.83.V.5, 1983.

UN General Assembly: 22nd session, A/C.1/PV.1515, New York, 1967a.

UN General Assembly: 22nd session, A/C.1/PV.1516, New York, 1967b.

Walker, G.: Beyond distribution and proximity: Exploring the multiple spatialities of environmental justice, Antipode, 41, 614–636, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2009.00691.x, 2009.

Walker, G.: Environmental Justice. Concepts, Evidence and Politics, Routledge, London, 2012.

White, H.: Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1973.

Deep-seabed mining, as discussed in this paper, refers to the extraction of minerals, like manganese, sulfide or cobalt, from deposits at several thousand meters below sea level. Mining the seabed involves considerable technical effort and substantial financial investments as well as high uncertainty in terms of the activity's economic viability and the possibility of causing environmental harm. A number of recent initiatives for DSM have focused on deposits in the exclusive economic zones of countries like Papua New Guinea. Other DSM initiatives are aimed at mining deposits in the so-called Area. The Area represents the entire seabed beyond the limits of national jurisdiction, a territory covering nearly 50 % of the global seabed (Christiansen et al., 2019). The Area is designated as the common heritage of mankind and has to be managed to the benefit of mankind today and in the future (Christiansen et al., 2019). The political responsibility for organizing and regulating deep-seabed mining in the Area lies with the ISA in Jamaica. As of 2018, the ISA has concluded 29 exploration contracts with an international group of contractors that comprises numerous states, state-owned entities, and private enterprises (Christiansen et al., 2019).

The surname Plainview carries an ambiguous meaning. On the one hand, it suggests a person who, in his ruthless pursuit of profit and power, tends towards a simplistic and therefore indifferent view of the world. On the other hand – and this is especially interesting considering our discussion of the ISA and DSM in general – it points to the protagonist's ability to grasp the situation and to take advantage of a scene that is confusing and opaque for most other people.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Methodology and scope

- The sound of discourse on deep-seabed mining

- Narrative structures

- Competing arguments, competing stories

- Conclusions – pitfalls and opportunities for critical narratives about DSM

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Methodology and scope

- The sound of discourse on deep-seabed mining

- Narrative structures

- Competing arguments, competing stories

- Conclusions – pitfalls and opportunities for critical narratives about DSM

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References