the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

(Re)claiming territory: Colombia's “territorial-peace” approach and the city

Angela Stienen

This article observes the Latin American debate on “territory” through the lens of the “territorial-peace” approach agreed in the peace accord between the Colombian government and the FARC guerrillas in 2016. It explores the different notions of territory entailed in this concept and shows that the territorial-peace approach builds on a political-programmatic understanding of territory due to its rural focus. An ethnographic analysis of the urban renewal programme PRIMED, implemented at the disputed urban periphery of Colombia's second city, Medellín, in the 1990s, demonstrates how this programme anticipated the idea of territorial peace in a conflictive urban context. The ethnography reveals the ambiguities and inconsistencies of the production of urban territory, both as state space and as the space of subaltern social groups, through territorial peacebuilding. The discussion why PRIMED challenges the political-programmatic understanding of territory in the territorial-peace debate concludes with highlighting why it makes a difference approaching territorial peace as a “political project to be achieved” or as an unpredictable process of territorialisation and why this distinction matters if the territorial-peace approach is to be extended to urban contexts.

- Article

(756 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

During the last 2 decades the dispute over land has taken on a marked particularity in Latin America in that peasant, indigenous, and Afro-descendant movements have come to claim “territory”. The conceptual and political implication of claiming territory rather than land has been interpreted as a shift from the demand of individual possession of land to the more political demand of collective possession, administration, and control of the means of production and thus to the struggle for collective sovereignties within the nation state (Vacaflores Rivero, 2009; Silva Prada, 2016; Salcedo García, 2015; Fernandes, 2013; Wahren, 2011; Sánchez, 2010).

Against this backdrop, it is significant that the peace agreement achieved between the Colombian government and the country's largest guerrilla organisation, the communist-inspired Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC-EP), in 2016 introduced the concept of Paz Territorial, (“territorial peace”). Coined as such by the High Commissioner for Peace of the Colombian government, Sergio Jaramillo, territorial peace has become a key concept for “re-imagining the nation” after the formal end of the longest-running armed conflict in Latin America (Cairo et al., 2018:1f). The inclusion of the concept of territorial peace into the peace agenda distinguishes the Colombian peace accord from similar agreements achieved in other countries affected by internal armed conflict. This approach challenges the exclusive perception of territory as “state space” (Brenner and Elden, 2009:365) as it brings to the fore Colombia's “parcellized sovereignties” (Anderson, 1974, quoted in Ballvé, 2012:619). These are territories produced by Afro-descendent and indigenous communities as well as by (non-ethnically defined) peasant populations and Colombia's insurgent groups. The territorial-peace approach is thus considered of wider geopolitical relevance beyond the Colombian case (Cairo et al., 2018).

Colombia's territorial-peace approach has not yet been explored much in academic literature (for an overview see Cairo et al., 2018, and Bautista Baustista, 2017). The term is inspired by contrasting and polysemous notions of territory: for the Colombian government, the police, and the Colombian army, territorial peace means extending state control over spaces “lost” for decades to guerrilla groups. The FARC-EP in contrast, stress that Colombia is configured in multiple territories and that to establish territorial peace, a “deep structural and cultural transformation” is needed (Cairo and Ríos, 2018:5; Bautista Bautista, 2017). Hence, the territorial-peace approach articulates two different and conflicting notions of territory: “territory” (in singular) as state space and “territories” (in the plural) as “self-governed spaces” that fragment the state space.

Scholars criticise both negotiating parties for conceiving territory in a reductionist and biased way. Both focused primarily on the countryside as the arena of Colombia's armed conflict. For a long time, both parties have regarded the disputed rural space as a “repository” of resources to fuel the war or to be exploited for economic reasons (Piazzini Suárez, 2018:7; Cairo et al., 2018). Cities and the urban dimension of Colombia's armed conflict are not explicitly addressed in the 2016 peace accord, and local experiences of peacebuilding have been explored almost exclusively in rural areas (Ruano Jiménez, 2019; Olarte-Olarte, 2019; Courtheyn, 2018; Oslender, 2018; Rodríguez Muñoz, 2018; Gruner, 2017; Forero and Urrea, 2016; Daniels Puello, 2015; Salcedo Gracía, 2015). Scholars complain that territorial peacebuilding is still underexposed in urban contexts, although the rural armed conflict has severely affected urban development in Colombia (Montoya Arango, 2018; Piazzini Suárez, 2018; Sánchez Medina, 2016; Zapata, 2015).

The aim of this article is to further this scholarship. I discuss an earlier initiative of territorial peacebuilding in a conflictive urban context through the lens of the 2016 territorial-peace approach. I revisit my ethnographic data on the “Programme for the Holistic Improvement of Substandard Settlements in Medellín” (Programa Integral de Mejoramiento de Barrios Subnormales de Medellín), abbreviated in Spanish as PRIMED, implemented in Colombia's second city Medellín during the 1990s (Stienen, 2005, 2016). The explicit goal of PRIMED was territorial peacebuilding to address Medellín's extreme urban violence in the 1990s (Alcaldía de Medellín, 1998; Consejería Presidencial para Medellín y su Ara Metropolitana, 1993). I show how this programme anticipated the 2016 territorial-peace approach in an urban context.

In the early 1990s, Medellín was regarded as a laboratory in which the tragedy of the Colombian conflict averaged 22 murders per day for a total population of 1.6 million.1 The majority of these victims were boys and young men, aged 12 to 33 years (Arias et al., 1994:30f). Many of these youngsters were members of rival milicias (vigilante groups influenced by Colombia's guerrilla organisations) and criminal gangs (established by the Medellín drug cartel). These groups were fighting violent turf wars in Medellín's irregularly constructed deprived neighbourhoods (Medina, 2006; Gutiérrez Sanín and Jaramillo, 2004; Angarita Cañas, 2003; Franco, 2003; Jaramillo et al., 1998). However, during the 1990s Medellín was also a city with an atmosphere of change. In 1991, Colombia's Political Constitution was totally reformed, and the new charter enacted new political and social rights. It also declared Colombia as a multicultural and pluri-ethnic nation. At that time, the constitutional reform was widely conceived as a “pact for peace and social integration” and raised the hope that it would guide Colombian society towards reconciliation, democratisation, and peace (e.g. Salcedo Gracía, 2015; Dugas, 1993). This was the context of vivid civil activism in Medellín during the 1990s. Experimental social and political initiatives were developed in the city to address the urban conflict. These initiatives included peace agreements with the illegal armed youth groups that operated in the city and pioneering initiatives of territorial peacebuilding through neighbourhood upgrading and urban redevelopment programmes (Stienen, 1998, 2005). PRIMED was the most iconic of these programmes.

Renewed interest in PRIMED in the territorial-peace debate (see e.g. Sánchez Medina, 2016) suggests that a closer look at this little-examined programme will introduce an urban perspective into this debate.2 In this article, I first reconstruct from different actors' perspectives the controversial and polysemous notions of territory in Colombia's 2016 territorial-peace approach. I contextualise these notions in Colombia's legal framework, established in the aftermath of the country's 1991 constitutional reform. This section shows that due to its rural focus, the territorial-peace approach builds on a political-programmatic understanding of territory. In the second section, I show why territorial peacebuilding in the city challenges political-programmatic notions of territory. Drawing on my ethnographic fieldwork on the (re-)territorialisation of Medellín's contested urban periphery in the framework of PRIMED during the 1990s, I examine how territorial peace was addressed in this conflictive urban context and detail the territorial disputes PRIMED provoked. My ethnographic field research focused on practices of territorialisation (see Stienen, 2005, 2016). I thus follow a processual and relational understanding of territory as a form of dispute along intersecting power relations rather than as their result.3 This approach allows me to elaborate why the production of urban territory through territorial peacebuilding blurred the dichotomy between territory as state space and as an instrument of political emancipation. Inspired by the suggestion of Brubaker and Cooper (2000) of not confusing “categories of (social and political) praxis” and “categories of (social and political) analysis”, in the concluding section, I discuss why it makes a difference approaching territorial peace as a “political project to be achieved” or approaching territorial peacebuilding as an ongoing process of territorialisation, which is unpredictable and produces unexpected social and political outcomes.

The concept of territorial peace emerged during the 4-year-long peace negotiations between the Colombian government and the FARC guerrillas as a result of the analysis of the origin and intensification of the armed conflict in the country. Both negotiating parties agreed that the root causes of the Colombian conflict have been the disputes over land and territory and that territorial peace had to be the central axis of the peace accord. There was consent that peacebuilding had to respond to the fragmentation of the territory of the nation state and to acknowledge the country's peripheral rural areas most affected by armed clashes. Many of these rural areas have been under the control of guerrilla groups for decades, and these groups have been the only institution to attend to people's needs (Gobierno de la República de Colombia and FARC-EP, 2016; see also Ruano Jiménez, 2019; Cairo et al., 2018; Bautista Bautista, 2017; Vargas and Hurtado de Mendoza, 2017; and Guarín, 2016).

Official data show that 60 % of conflict-related armed confrontations have been concentrated in these rural areas, mainly located in Colombia's border departments. These confrontations have been disputes over land and (natural) resources.4 Land concentration in Colombia has radically increased during the last 2 decades and so has the number of forcibly displaced persons, with 7.4 million in 2017, especially peasants and Afro-Colombian and indigenous people, who have been the most affected by the violent conflicts over land occupation and territory (UNHCR, 2017).5 Mondragón (2010) calls the extensive land-grabbing and displacement in Colombia “accumulation through war”. He highlights that since the 1990s, the neoliberal economic opening of Colombia provoked new transnational investments, mainly in extractive industries and infrastructural projects, and thus increased territorial disputes. The author argues, “In Colombia not only are there displaced people because there is war, but there is war to displace people” (quoted in Ordóñez Gómez, 2012:8; my translation).6 Against this backdrop, the High Commissioner for Peace of the Colombian government, Sergio Jaramillo, stressed that territorial reparation together with truth and reparation for the individual and collective victims of the war are key issues in building territorial peace (Jaramillo, 2014; see also Cairo et al., 2018; Forero and Urrea, 2016; and Salcedo Gracía, 2015).7

The territorial-peace approach seeks to enforce key principles of Colombia's 1991 constitutional reform throughout the territory of the nation state. These principles include strengthening decentralisation (political, fiscal, and administrative), building “strong institutions”, and expanding (liberal) civil rights together with citizen participation (Jaramillo, 2014; see also Cairo et al., 2018; Bautista Bautista, 2017; Guarín, 2016; and Salcedo Gracía, 2015). To understand these principles, it is important to know that Colombia's reformed 1991 political charter was drafted by a constituent assembly that had been elected by popular vote and was integrated, among others, by delegates of grassroots organisations, ethnic minorities, and demobilised former leftist guerrilla organisations. It defined Colombia as a social state based on the rule of law and enacted multiple basic civil and political rights as well as administrative decentralisation and mechanisms for citizen participation. It also declared Colombia as a multicultural and pluri-ethnic nation (e.g. Pineda Camacho, 1997). To achieve a modern liberal state reform necessary to engage in globalisation, Colombia's 1991 constitutional reform consolidated the political and administrative decentralisation in the country, giving continuation to the neoliberal structural adjustments of the late 1980s and 1990s. The decentralisation of political, fiscal, and administrative decision-making from national to municipal entities followed global development guidelines such as “institution building” and “good governance” promoted by the World Bank (Guarín, 2016; Ballvé, 2012; Robledo Silva, 2010; Moreno, 1997). But decentralisation was also repeatedly called for by the country's left guerrilla organisations in periodic peace talks with the Colombian government. These organisations sought to open new scopes for citizen participation on the municipal level (Ballvé, 2012). This means that Colombia's political and administrative decentralisation pursued two conflictive goals: to make spaces governable in order to expand neoliberal capitalist accumulation and to afford local communities the self-determination of local development and the autonomy of their territorial entities (García Lozano, 2016; Ballvé, 2012; Rebledo Silva, 2010; Hernández Peña, 2010; Castro, 1998; Moreno, 1997). The adoption of two crucial reform laws, the Development Planning Act of 1994 and the Territorial Development Act of 1997, have ensured these conflictive objectives of the 1991 constitutional reform.8 These laws have been considered key “state policy and planning instruments” to enable both “the adequate political-administrative organisation of the nation” and the participatory co-construction of territorial development plans by municipalities and local communities (Asher and Ojeda, 2009, quoted in Ballvé, 2012:607f; see also Guarín, 2016). Moreover, by declaring Colombia as a multicultural and pluri-ethnic nation, the reformed charter laid the legal foundations to enhance the autonomous and collective administration of local territorial entities by rural populations (ethnically and non-ethnically defined; e.g. Pineda Camacho, 1997).

In what follows, I show how this legal framework that goes back to the 1991 constitutional reform influenced the territorial-peace approach and the conflicting understandings of territory on which the term territorial peace is based. I highlight how on the one hand, territory is considered a political instrument of state control to subordinate primarily rural populations under (neoliberal) capitalist development and the interests of transnational corporations (see e.g. Silva Prada, 2016:643). On the other hand, territory is regarded as a political instrument used by these populations to position themselves in front of the state as collective political subjects with the right to local autonomy and self-government (Courtheyn, 2018; Silva Prada, 2016; Vacaflores Rivero, 2009; Wahren, 2011; Agnew and Oslender, 2010). In this order of ideas, the territorial-peace approach furthers what Piazzini Suárez (2018:7f) calls the “hyper-territorialised perception” of space in Colombia, both in politics and academic discourse. The controversial understandings of territory encompassed by the territorial-peace approach follow conflicting intentions and antagonist political and societal projects (for these projects, see e.g. Ruano Jiménez, 2019; Olarte-Olarte, 2019; Montañez-Gómez, 2016; Cairo et al., 2018; Courtheyn, 2018; Bautista Bautista, 2017; Maldonado, 2016; Zubiría, 2016; Daniels Puello, 2015; and Salcedo Gracía, 2015). As Fernandes (2013:119) rightly argues, political intentionality is crucial when it comes to broadening or narrowing the meaning assigned to specific terms. Hence, it is insightful to trace back from different actors' perspectives the controversial notions of territory attached to the term “territorial peace”.

2.1 Territorial peace and state space

The High Commissioner for Peace of the Colombian government, Sergio Jaramillo, stressed that territorial peace implies that “the constitutional rights of all Colombians equally throughout the territory” are guaranteed. He said that this requires “a logic of inclusion and territorial integration” to be imposed based on “a new alliance between the State and local communities to jointly build institutionality in the territory”. But he also emphasised that “this does not mean that communities organize themselves” (Jaramillo, 2014:5). He specified that building “strong institutions” includes both “the presence of some state entities” and the existence of “practices and norms that regulate public life and produce welfare” (Jaramillo, 2014:5). It also includes “rural development” in order to “transform the conditions of the countryside” and “close the enormous gap between the city and the countryside” (Jaramillo, 2014:5). The High Commissioner underlined that, for the Colombian government, territorial peace thus does not only mean “demobilising armed groups”, but “to fill the space, we [the state] have to institutionalise the territory, and we have to do this together with the communities” (Jaramillo, 2014:4, 6; my translation of the quotations).

The High Commissioner's formulation suggests that the Colombian government understands the territorial-peace approach as an instrument to give continuity to the rationale of various rural programmes in Colombia's history that aimed to consolidate the state by institutionalising the territory (Jaramillo, 2014:5). Programmes such as the National Territorial Consolidation and Reconstruction Programme, implemented in 2011 and managed by the Special Administrative Unit for Territorial Consolidation, has sought to “bring the state” to so-called “lawless peripheral rural spaces”.9 These rural areas have been disputed space for decades because they have been considered “strategic territories”, “rich in resources such as petroleum, biodiversity, mining, and water, i.e. hydroelectric energy”, as the programme director Germán Chamorro de la Rosa explained (quoted in Derks-Normandin, 2014:21). This representation of Colombia's disputed rural space is also expressed in the words of the president of the state-owned Colombian petroleum company, Ecopetrol, Juan Carlos Echeverry in relation to the 2016 peace accord. He stated in 2016 that “peace will allow the extraction of more mineral oil from areas which have been inaccessible due to the armed conflict” (quoted in Bautista Bautista, 2017:102; my translation; see also DIÁLOGO-Digital Military Magazine, 2014).10 These assertions indicate that behind the immediate goal of the Colombian government to consolidate the state by institutionalising the territory in peripheral rural areas lurks the objective of making spaces governable to expand capitalist accumulation in accordance with the interests of transnational corporations.

The vision of territorial peace presented by the Colombian government stands in sharp contrast to that of the FARC-EP. From their point of view, to build territorial peace the territorial practices of indigenous and Afro-descendant communities as well as (non-ethnically defined) peasant populations need to be taken into consideration. Over the last 3 decades, these social groups have challenged the sole sovereignty of the nation state by constructing territorial sovereignties within the national territory (see Gruner, 2017; Silva Prada, 2016; Ulloa, 2012; Agnew and Oslender, 2010; García Lozano, 2016; Wahren, 2011; and Vacaflores Rivero, 2009).

2.2 Territorial peace and spaces of counter-sovereignty

In his statement on the FARC-EP's vision of territorial peace, Jesús Santrich, a key delegate of the FARC-EP at the peace talks with the Colombian government between 2012 and 2016, alluded to the cosmovisions of indigenous and Afro-descendant peasant communities. In an interview in 2017, he stated that the vision of the FARC-EP “is based on the exchange with Mother Earth; it is from that point that we introduced the concept of `good living' which is a derivation of the Aymara and Quechuan concept sumak kawsay” (quoted in Cairo and Ríos, 2018:4–5).11 Santrich also emphasised that “decentralisation” is a basic claim in the vision of territorial peace of the FARC-EP in that “all has to be consulted with the local communities in their territories. The government cannot just impose its projects” (quoted in Cairo and Ríos, 2018:4).

In this statement, the territorial-peace approach is represented as a response to the demands of peasant movements and ethno-territorial communities to recognise what has been described as the country's highly diverse geographies with their multiple social, economic, and political histories (Rodríguez Muñoz, 2018; Oslender, 2018). Hence, the territorial-peace approach is presented as a “method” to expand the collective recognition of (ethnically and non-ethnically defined) rural communities, to ensure their social rights, and to produce changes in the structure of land tenure and wealth distribution (Salcedo Gracía, 2015; see also Sánchez Medina, 2016; and Zapata, 2015). This representation of territorial peace refers to the fact that by law peasant and ethno-territorial communities must be included in land use decisions and that the (respectful) coexistence of diverse territorialised production systems, cosmovisions and forms of life must be guaranteed (Romero, 2015, quoted in Zapata, 2015:4; Gruner, 2017:175).

This legal dimension is derived from Colombia's 1991 constitutional reform and the country's above-mentioned Development Planning Act of 1994 and Territorial Development Act of 1997. The constitutional reform facilitated the introduction of three territorial figures for which Colombia's peasant and ethno-territorial movements had fought hard since the 1980s: indigenous territories12, collective land titling to Afro-descendant communities13 and Peasant Reserve Zones.14 Indigenous territories and the territories of Afro-descendant communities are legally constituted through the enactment of collective ownership of land traditionally occupied by these ethnically defined communities. Ancestral practices and cosmovisions of these communities are legally recognised as well as their places of worship, the collective management of these territories, and the use and conservation of these territories' natural resources. Especially indigenous territories are considered by law as “inalienable, imprescriptible and unseizable” (Rodríguez, 2018; Duarte and Castaño, 2017; Gruner, 2017).

The legal figure for the constitution of Peasant Reserve Zones, by contrast, is different. By Colombian law, peasants are not primarily defined in ethnic terms, and thus they are not considered a “collective subject of law” such as indigenous and Afro-descendent communities. Peasant Reserve Zones were constituted as a legal figure of land management as well as to ensure mechanisms of participation and consultation of peasant organisations (Rodríguez Muñoz, 2018; Silva Prada, 2016; Ordoñez Gómez, 2012). Hence, Peasant Reserve Zones have a different legal status than the collective territories of indigenous and Afro-descendant communities, which are considered self-governed subnational territorial entities which receive transfer funding from the government.15

These three legal figures have influenced the 2016 peace agreement. Colombia's so-called ethno-territorial movements – indigenous and Afro-descendant Colombians together with grassroots movements – managed to introduce a “differential approach” to the final document of the peace agreement. This approach takes into consideration that the systematic violence against groups defined by race and ethnicity (as well as by age, gender, and sexual orientation) has diverse territorial dimensions (Koopman, 2018; Gruner, 2017). The “ethnic chapter” of the final document of the peace accord, for instance, emphasises the self-determination, autonomy, and self-governance of the territories of ethnically defined communities in Colombia and stresses that the rights of these groups to their territories and resources need to be respected and protected. This implies “the recognition of ancestral territorial practices, the right to the restitution of collective property rights, and the implementation of legal mechanisms to protect and secure ancestrally and/or traditionally occupied or owned lands and territories” (Gobierno de Colombia and FARC-EP, 2016:206–207; my translation). In addition, the final document also underlines that the accorded comprehensive rural reform (one of the key issues in the peace agreement) will include “programmes agreed as part of this reform [that] will have a territorial and gender approach which involves recognising and taking into account the needs and characteristics as well as particular economic, cultural, and social features of the country's diverse territories” (Gobierno de Colombia and FARC-EP, 2016:11; my translation).

It is important to highlight that these points in the final peace agreement are inspired by a document elaborated by Afro-descendant and indigenous people. This document exposes territorialised alternatives to capitalism (see Gruner, 2017). These alternatives are considered counter-hegemonic territorial regimes that have not only fragmented the territory of the Colombian nation state but have also challenged “the violent logic of capitalist accumulation” (Silva Prada, 2016:643; see also Solís et al., 2018; Rodríguez Muñoz, 2018; Bautista Bautista, 2017; Duarte and Castaño, 2017; Gruner, 2017; Duarte and Bolaños Trochez, 2017; García Lozano, 2016; Salcedo Gracía, 2015; and Ulloa, 2012). This notion of territory refers on the one hand to the construction of a “dignified” and “good life” that confronts the commodification of land and territorial homogenisation through dispossession imposed by multinational capital (mining companies, agro-industry, etc.). On the other hand, this notion is linked to alternative conceptions of “citizen rights” which go beyond the liberal principles of individual rights and include collective rights of social groups and ethnically defined communities (see Bautista Bautista, 2017; Silva Prada, 2016; Vacaflores Rivero, 2009; Ballvé, 2012; Agnew and Oslender, 2010).

2.3 Territory in Colombia's territorial-peace approach

The territorial-peace approach agreed between the Colombian government and the FARC-EP is a disputed field in that it follows conflicting notions of territory which refer to antagonistic societal projects. There is thus an inherent tension in this approach between two understandings of what is referred to as “state space” (see Brenner and Elden, 2009). State space is either understood in terms of what Lefebvre calls “abstract space”, i.e. a space to serve the abstract purpose of “capitalist accumulation” (Lefebvre, 1991:53, 387; Brenner and Elden, 2009:368–369), or it is conceived in terms of “multi-territoriality” (Haesbaert, 2013), i.e. as a multiplicity of spaces which are appropriated to serve human needs in Lefebvre's sense (Lefebvre, 1991:52, 393–394).

2.3.1 State space as abstract space

In a synthesis of Lefebvre's argument, Brenner and Elden (2009:363) write that abstract space is “the political product of state spatial strategies – of administration, repression, domination and centralized power”. Lefebvre stresses that abstract space is “instituted by a [modern] state, it is institutional”, it is “politically instrumental” in that it facilitates processes of capital accumulation, and it “serves those forces which make a tabula rasa of whatever stands in their way, of whatever threatens them” (Lefebvre, 1974:328, 1991:285, quoted in Brenner and Elden, 2009:358). Abstract space is thus a “space of domination”, which is “inherently violent” (Lefebvre, 1991:164–165; 387). As mentioned above, the objective of the Colombian government is to consolidate state space by institutionalising the (politico-juridically defined) territory of the nation state through the territorial-peace approach. With this goal the government follows the basic assumption that the targeted peripheral rural space is an “empty space” because it lacks state institutions; its population is primarily addressed as “deficient” and as a “victim” (see Jaramillo, 2014). “Filling” this space with “strong institutions” (Jaramillo, 2014) appears as a “state spatial strategy” that seeks to make this space “politically instrumental” (Lefebvre, 1974:328, 402–403, 1991:285, 349, quoted in Brenner and Elden, 2009:359) for the exploitation of human and natural resources – previously inaccessible because of the war – in order to expand capitalist accumulation. Scholars have explored how during the last 3 decades (ethnically and non-ethnically defined) peasant communities have built their own alternative “institutionality” in these rural areas in the midst of the war. These scholars criticise that the government's vision of territorial peacebuilding does not recognise these experiences developed on the fringes of the state (Courtheyn, 2018; Cairo et al., 2018; Bautista Bautista, 2017; Paladini, 2016; Daniels Puello, 2015). They argue that the Colombian government perceives the disputed rural space as either “biophysical support” (Piazzini Suárez, 2018:6) or as a container “filled” with unexploited natural resources controlled by grassroots organisations established outside the control of the state (often influenced by insurgent groups; Bautista Bautista, 2017:105). Bautista Bautista (2017:105) argues that the intention of the government is to either replace or co-opt these organisations through the territorial-peace approach. From this point of view, territorial peace as intended by the Colombian government is a “terminal point” where “state control over land and population” is generalised over the entire territory of the nation state (Courtheyn, 2018:1454; Bautista Bautista, 2017:105; see also Olarte-Olarte, 2019). The territorial-peace approach appears as a strategy of consolidating state space as abstract space, i.e. as the inherently violent “space of domination” Lefebvre (1991:164–165; 387) refers to (see also Lefebvre, 2009:95ff).

2.3.2 State space as multi-territoriality

In Colombia and other Latin American countries, however, the conception of state space as abstract space has been decentred and differentiated, as outlined above (see Schwarz and Streule, 2017; Agnew and Oslender, 2010; Fernandes, 2005; and Porto-Gonçalves, 2002, 2009). Agnew and Oslender (2010:197) conceptualised the self-governed territories constructed by subaltern collective social subjects (such as ethnic peasant communities) as “superimposed” or “differential territorialities”. They overlap with the state territory and constitute social spaces of counter-sovereignty. From this perspective, the territory of the nation state is considered only one territory among many, as Ballvé (2012:605) highlights. This situation is conceptualised as “multi-territoriality” (Haesbaert, 2013). The vision of territorial peace presented by the FARC-EP addresses this situation.

In Colombia, the configuration of what is referred to as “multi-territoriality” has been ensured in rural areas through legal procedures established by the state. The analysis of Ng'weno (2007) of Afro-descendant communities in Colombia shows that the disputes of these communities over territory have not sought to dissolve and replace the (politico-juridically defined) territory of the nation state. These disputes have rather aimed to achieve the recognition and protection by the state of collective rights to territorialise and control parts of the national territory. Hence, ethnically defined peasant communities have claimed both that the state recognises the existence of their sovereign territories as part of the state space and the state protects these territories (García Lozano, 2016; Silva Prada, 2016; Salcedo Gracía, 2015; Fernandes, 2005, 2013; Ng'weno, 2007; Vacaflores Rivero, 2009). This means that building counter-sovereign territories in Colombia paradoxically requires both seeking state legitimacy and protection and simultaneously challenging and confronting state authority and territory as abstract space (for these processes, see Ulloa, 2012; Vacaflores Rivero, 2009; Carroll, 2011; Agnew and Oslender, 2010; and Ng'weno, 2007, 2013). Ng'weno (2007, 2013) demonstrates that the claims to territory in Colombia and throughout Latin America are largely rooted in struggles around ethnicity, culture, and history. To claim land and territory as collective subjects of law, individuals have had to prove their belonging to an ethnic group recognised as such by state law. Hence, multi-territoriality has been established by both political contestation and differential state regulation.

Multi-territoriality refers to a conception of “territoriality” as a “field of action and possibilities” built through “marking borders that limit the action of other agents” and exclude them from these socially constructed fields, as Silva Prada (2016:638f) emphasises. The conception of multi-territoriality thus implicitly carries the notion of power (and power struggles) due to multiple appropriations, exercises of dominion, and control of portions of the earth's surface, i.e. of land and resources. Silva Prada stresses that “the communities as collective actors build their territories through the appropriation of spaces with projects that give them a sense of belonging to these appropriated territories” (Silva Prada, 2016:638; my translation). It can thus be argued that peasant communities (ethnically and non-ethnically defined) strive for territory as “bounded space” with an “inside” and “outside”. In analogy with the state, they seek to build their own alternative “institutionality” in order to establish counter-sovereign territorialities. Bautista Bautista (2017:108) points to the fact that the enforcement of the three before-mentioned legal figures that regulate the right of these peasant communities to self-governed territories and to the control of their resources however has been a matter of violent disputes. This author argues that achieving multi-territoriality in Colombia, i.e. recognising territories of counter-sovereignty that dispute the abstract space of capital, has been extremely arduous.

In summary, tracing back the controversial notions of territory inherent in the territorial-peace approach from different actors' perspective helped to understand why the rural focus of the territorial-peace approach contributes to furthering the above-mentioned “hyper-territorialised perception” of space in political and academic discourse in Colombia (Piazzini Suárez, 2018:7f): territory is (re)claimed by both the state and peasant communities as a political instrument and a political project. In the territorial-peace debate, territory is typically conceived through the lens of these antagonistic political projects which collide in Colombia's rural space: on the one hand, the project of the Colombian government of consolidating state space to expand the export-oriented capitalist development model based on extractive economies, on the other hand, the collective projects of peasant communities to establish counter-sovereignties and expand non- and anti-capitalist relations of agrarian production as existential support of a dignified, self-determined life. Against this backdrop, it is not surprising that critical scholars' research on territorial peacebuilding has mainly focused on peasant communities and that there has been a tendency to juxtapose the state (conceived as monolithic) to these peasant communities (often perceived in terms of idealising conceptions of community and collective action).

2.3.3 Redefining state space in the city

There is hardly any literature on whether and how the tensions, contradictions, and paradoxes inherent in the territorial-peace debate and presented in the first section of this article also apply to urban contexts.16 In the second section, I explore these questions. Drawing on my ethnographic data on the pioneering urban renewal programme PRIMED, I present how this programme sought to confront Medellín's extreme urban violence through territorial peacebuilding in the 1990s. I primarily identify the territorial disputes it produced. My argument is that PRIMED anticipated – in a conflictive urban context – the territorial-peace approach accorded in the 2016 peace agreement. Important analogies between the objectives of PRIMED's territory-focused urban peacebuilding in the 1990s and the objectives of Colombia's 2016 territorial-peace approach can be detected: while the former sought to pacify the city through (re)territorialising the city's edge (back then Medellín was considered one of the most violent cities of the world), the latter aims to pacify the nation through (re)territorialising the country's peripheral rural areas. Two main objectives of territory-focused peacebuilding can be identified for each case: (1) to address the perceived “crisis of state authority” in peripheral areas strongly affected by armed conflicts – either in the city (PRIMED) or in the countryside (the 2016 territorial-peace approach) – and (2) to redefine state space by taking into consideration the “parcellised (micro-)territorial sovereignties” that have superimposed and interpenetrated the territory of the nation state.

The above-quoted High Commissioner for Peace of the Colombian government outlined that the territorial-peace approach wants to reach these objectives in Colombia's countryside through “combining national coordination and resources with local knowledge and strength” (Jaramillo, 2014:5f; my translation). Its intention is to build a “partnership” between state authorities and local communities which will “come together to build the so-called `public sphere' in the territories and deliberate common purposes that will recover the basic rules of respect and cooperation” (Jaramillo, 2014:6; my translation). Daniels Puello (2015:164f, 154) underlines that territorial peacebuilding requires citizen participation and protagonism both in formulating territorialised public policies that materialise the constitutional rights and in exercising political power in these territories.

With this in mind, my analysis of PRIMED gives empirical evidence for what Brenner and Elden (2009:367) emphasised in their discussion of Lefebvre's conceptualisation of the production and transformation of territory as state space. These authors stress “whereas the state and capital attempt to `pulverize' space into a manageable, calculable and abstract grid, diverse social forces simultaneously attempt to create, defend or extend spaces of social reproduction, everyday life and grassroots control (autogestion)” (Brenner and Elden, 2009:367).

My analysis highlights the multiplicity and incompleteness of what is referred to as “state space”. It discloses how power structures are incorporated into the urban territory through laws, rules, and norms and how they are contested.17 It shows why from the perspective of urban territorial peacebuilding the dichotomy between territory as state space and as an instrument of political emancipation appears blurred.

3.1 PRIMED and territorial peacebuilding

The Programa Integral de Mejoramiento de Barrios Subnormales de Medellín (PRIMED; Programme for the Holistic Improvement of Substandard Settlements in Medellín) was implemented between 1993 and 1999 in 15 settlements of three urban districts at the very edge of Medellín. The explicit objective of this programme was territorial peacebuilding to address Medellín's extreme urban violence in the 1990s (Alcaldía, 1998; Municipio de Medellín, 1996; PRIMED, 1996; Consejería, 1993). I followed the implementation of PRIMED during the late 1990s and moved to one of the three renewal areas of the programme, the upper part of the district Comuna 6, after comprehensive archive work, informal conversations, and tape-recorded interviews with programme officers. In the selected renewal area, I conducted fieldwork as a participant observer during a period of 2 months.18

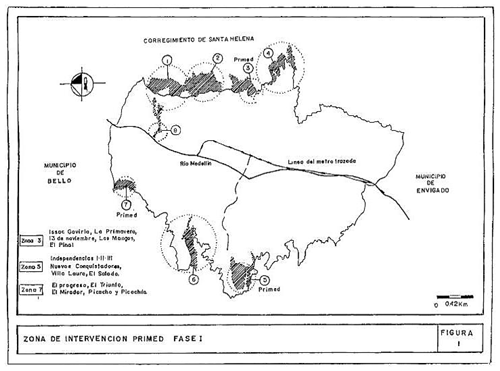

Figure 1Substandard settlements at Medellín's urban periphery in 1993 and PRIMED renewal areas: Zona 3 (Comuna 8), Zona 5 (Comuna 13), Zona 7 (Comuna 6). (Source: Consejería, 1993:57).

The settlements of the PRIMED renewal areas had expanded irregularly outside the urban perimeter at the city's steep hillsides during the late 1970s and '80s mainly as a consequence of interurban forced displacement in the wake of the city's increasing violence and economic crisis. Until the start of PRIMED in 1993, these self-constructed settlements, built on squatted land or on land sold illegally by “pirate urbanisers” (Coupé, 1993), were not officially recognised by the municipal planning office. However, Empresas Públicas de Medellín, the city's efficient public utility company, had partly equipped the settlements with water, power, and sewerage in response to the insistent demands of local grassroots organisations. Residents had organised to fight eviction by the police, and they put pressure on the municipality to provide basic services in the settlements. In 1993, the three districts of the PRIMED renewal areas totaled a population of approximately 51 100 residents (around 3 % of Medellín's total population of 1.6 million at that time and 20 % of the urban population living in irregularly built settlements). The municipal planning office categorised these settlements as “high-risk areas” and “ungoverned spaces”. They had continuously been facing the threat of deadly mudslides due to the geological instability of the city's steep hillsides. Moreover, they had been governed by illegal armed youth groups, both milicias influenced by Colombia's guerrilla groups and criminal gangs established by organised crime (Alcaldía, 1998; Municipio, 1996; Consejería, 1993). Homicide rates in Medellín culminated in 1993, with an average of 311 per 100 000 inhabitants. Although these rates dropped after Pablo Escobar, the iconic head of the Medellín drug cartel, was killed in December 1993, the average of 203 in 1996 and of 167 in 1999 was still high (Gil Ramírez, 2009:64, Jaramillo et al., 1998:110ff). Most victims were boys and young men, engaged in violent turf wars fought between rival milicias and criminal gangs, who controlled most of Medellín's deprived neighbourhoods.19 In the settlements selected to be upgraded by PRIMED, insurgent youth milicias had assumed some state-like practices in the face of the largely absent state authority. The settlements had thus gained the reputation for being “red zones”.20

In Medellín youth milicia groups emerged in the late 1980s as either independent neighbourhood vigilante groups or insurgent milicia units backed by Colombia's guerrilla groups. They sought to eradicate criminal gangs from disadvantaged neighbourhoods by force of arms and to institute their own model of self-government often under an insurrectionary perspective. At that time, they were mostly composed of the children of the families living in these neighbourhoods. The groups provided their communities with security and community services which were not provided by the state and extorted protection money from the residents. Their activities included night patrols, the resolution of domestic and neighbourhood disputes, recreation and sports, and activities to embellish the neighbourhoods. At that time, the milicias enjoyed broad popular support and during the 1990s, they rapidly expanded in Medellín and eventually controlled a quarter of the city's deprived neighbourhoods (Bedoya, 2010:109f, Medina, 2006; Jaramillo et al., 1998). In 1994 some milicia groups reached a peace agreement with the Colombian government and demobilised as their private protection services were given official credence through the constitution of a cooperative set up for “vigilance and community services”, known as Coosercom. Milicia groups linked to Colombia's main guerrilla groups, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN), however, rejected this agreement and united to occupy the territories of the demobilised groups. In armed confrontations with Coosercom members, accused of abuses against civilians and involvement in criminal activities, the insurgent milicia groups killed several hundred members of Coosercom, and in 1996 the municipality dissolved the cooperative (see Hylton, 2007, 2014; Rozema, 2008; Medina, 2006; Gutiérrez and Jaramillo, 2004; and Jaramillo et al., 1998).

The PRIMED renewal areas were affected by the armed turf wars between these rival milicia groups and between milicia groups and criminal gangs from neighbouring districts. The settlements were criss-crossed by invisible frontiers between micro-territorialities over which the armed youth groups disputed control with each other. Residents were literally confined in these micro-territorialities as transgressing the invisible frontiers involved the risk of getting caught in crossfire. This territorial order determined residents' daily routines. In the renewal area of Comuna 6, for instance, parents took their children from school because of frequent armed clashes right in front of the school. Residents took long detours to get to work, or they no longer dared to leave their dwellings anymore. Hardly anyone from outside found it possible to safely enter the settlements, including the police. In 1993, the PRIMED officers negotiated access to the settlements with the illegal armed youth groups. A young programme officer who worked in the local PRIMED office in Comuna 6 explained that until 1995 heavy shooting often started in front of the office after she had just entered the office. But she said that the armed youth groups respected PRIMED, generally informing her in advance if it was too dangerous to go to the office.21

In 1995, the municipality's Oficina de Paz y Convivencia (Office for Peace and Coexistence) backed negotiations around “pacts of non-aggression” between armed youth gangs all over Medellín and provided some financial support. These informal agreements turned the city's invisible frontiers into Fronteras de convivencia (frontiers of peaceful co-existence). But the armed youth groups continued exercising territorial control and extorting protection money in these neighbourhoods. This was also the case in the settlements of the three PRIMED renewal areas. Residents and the programme officers still had to deal with the armed youth groups' claims for territorial control. However, the pacts facilitated both the implementation of PRIMED and residents' engagement with the programme. Residents could now cross the invisible frontiers between the established micro-territorialities without risking being caught in crossfire. The pacts also reduced the risk for outsiders to enter the settlements. Hence, it was possible for me to move to the PRIMED renewal area of Comuna 6 in September 1997 to conduct fieldwork there during a period of 2 months.

The outlined processes of territorialisation at the very edge of Medellín can best be understood in terms of Silva Prada's above-quoted notion of “territoriality” (2016: 638f): These were socially constructed, self-governed “fields of action and possibilities” established through the appropriation of land over which the settlers disputed control with the (local) state. These spaces were signified symbolically by “communities of destiny”, forged through the collective resistance to being expelled from the city by the police. However, these spaces were fragmented by “invisible frontiers” violently constructed by illegal armed youth groups to confine the residents into micro-territorialities over which these groups exercised control. The PRIMED renewal areas were thus a dense space in Porto-Gonçalves' sense, over-signified by a multiplicity of conflicting uses and symbolic meanings (2002:230; see also Fernandes, 2005:276).

What follows intends to show how state control over the urban periphery had been negotiated in the context of PRIMED. I highlight the way the “crisis of (state) authority” (Gramsci, 1971:210, quoted in Ballvé, 2012:606) has been confronted by PRIMED. In his analysis of “everyday state formation” in Colombia's strongly disputed Urabá region, Ballvé (2012) proposes to conceive territorialisation in Colombia in terms of Gramsci's conception of the “integral state”, which includes both government and civil society. Inspired by this argument, I explain how PRIMED produced state territory in this integral Gramscian sense.22 The programme implemented government projects while also inciting civil society initiatives. PRIMED's practices of “de- and re-territorialisation” (Fernandes, 2005:279) were comprehensively influenced by residents' initiatives “to create, defend or extend spaces of social reproduction, everyday life and grassroots control” (Brenner and Elden, 2009:367f). Approaching PRIMED from the perspective of the “integral state” helps to unsettle normative binaries such as state/non-state, public/private, formal/informal, and legal/illegal and bring to the fore the divergent actors engaged in the production of state territory in the renewal areas as well as their conflicting interests and practices (see also Ballvé, 2012:611f).

In this order of ideas, it is necessary to discuss the de- and re-territorialisation practices of PRIMED also in relation to counter-insurgency. Following Elden's conception of “territory as political technology” (Elden, 2010:810f), I ask whether the re-territorialisation of Medellín's urban periphery by PRIMED can be interpreted as counter-insurgency that aimed to undermine both the ability of insurgent armed groups to control spaces and populations at the city's edge and residents' defiant everyday practices of territorialisation. I show that PRIMED was more complex. The programme not only established what Ballvé (2012:613) calls “the everyday territorial `workings' of the state”, reaching from formal law enforcement and expanding public services to imposing normative standards and routinised bureaucratic procedures. It also contributed to the empowerment of the formerly stigmatised residents in the settlements, “abandoned” by the state, by addressing and recognising them as subjects of law and acknowledging their everyday practices of territorialisation.

3.2 Establishing state control over the urban periphery

PRIMED was encouraged by the Consejería Presidencial para Medellín y su Area Metorpolitana (the Presidential Office for Medellín and the Metropolitan Area). The national government created this entity in 1990 to direct resources to local initiatives that addressed the city's social crises and alarming violence. PRIMED was co-funded by the Colombian government, the German-government-owned development bank “Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau” (KFW), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the municipality of Medellín. PRIMED represented a historical shift in the way irregularly constructed settlements on Medellín's steep hillsides had usually been addressed by the state. Instead of violently evicting the settlers and destroying their illegally built settlements, PRIMED sought to formalise and consolidate these settlements with measures that mitigated geological risks and with social investments (Alcaldía, 1998; Municipio 1996; Consejería, 1993). Hence, the programme recognised the efforts and achievements of the residents and secured these collectively built territories by legalising and incorporating them into the city. Designed in the wake of the 1991 constitutional reform, PRIMED sought to put into practice the idea that after the constitutional reform “Colombia has fully entered the era of citizen participation” (PRIMED, 1994:4; my translation). The professionals who designed the programme believed that “the new constitution enacted a new social contract based on participation, justice, and the recognition of civil rights” (PRIMED 1994:4; my translation). The following statements made by some of these professionals in a group interview reveal how the overarching goal of PRIMED in relation to peacebuilding connects to basic ideas of the 2016 territorial-peace approach:

“[In PRIMED] two goals came together. One was improving the life of the inhabitants of the 15 settlements with a comprehensive urban programme. But at the same time there was another commitment. We wanted to change the internal structure of the municipality; we wanted to democratise the municipality, to adjust it to the new rules of the game imposed by the Constitution. […] We belong to a generation of professionals with a lot of illusions; we believed in the utopias of the 1960s, '70s, '80s, but during the last 10 years we got frustrated as this city touched the bottom of the crisis […]. We realised that it is no longer the guerrilla that will bring change. Change needs to be done from the institutionality too; a civil society without a strong state does not work, and a strong state without a civil society does not work either. […] We wanted to move forward, starting from the Constitution. One of its main principles is to strengthen the municipality. The construction of conditions for living together peacefully and of the country we dream of starts from the municipality. In other words, PRIMED was not only designed for the subnormal neighbourhoods, this programme was designed for the city and for the whole country”.23

Integrated into the former Social Housing Corporation of the Municipality of Medellín (CORVIDE), PRIMED followed a holistic inter-institutional approach in urban upgrading, at that time considered unique in Latin America. The programme coordinated in the renewal areas territorially focused activities of different entities in the nation state and the municipality of Medellín. These activities included measures of mitigating geological risks, expanding the basic infrastructure (paths, roads, parks), completing basic services (water piping, power, sewerage), improving housing, and granting formal property titles to the residents. The programme also encouraged universities, local NGOs, small private firms, cooperatives, grassroots organisations, residents, and international donors to coordinate territorially focused activities in the renewal areas with each other and with the state. Following the legal framework enhanced by the 1991 Political Constitution, PRIMED also tried to build leadership among the residents. Residents and their grassroots organisations were trained by progressive local NGOs in participatory local planning, budgeting, project management, and in how to get a legal status to submit collectively elaborated small development projects to the municipality or to private and non-profit entities for funding.24

In short, PRIMED sought to build (state) institutionality in the settlements at Medellín's urban periphery. This included ensuring both the municipality's responsibility to provide the settlers with basic public services and the settlers' right and obligations to the city. Streets and addresses were formalised; the settlers were registered by location and prepared by the programme to pay fees and taxes. This was conditioned on their individual property rights and on the provision with basic public services and facilities by the municipality and the legalisation of the settlements (Stienen, 2005; Alcaldía, 1998; Municipio, 1996; Consejería, 1993). As PRIMED established offices physically in each of the three renewal areas, the programme thus constituted what Ballvé calls in his analysis of Colombia's Urabá region “a material and a symbolic `marker' of territorialized meaningful state presence” (2012:613). These decentralised PRIMED offices allowed the residents to have direct contact with representatives of the state in their everyday space.

But PRIMED had a “hidden agenda” too. I found out about this through an interview with a former PRIMED officer who had also participated in the design of the programme. He had a higher position in the local administration at the time of the interview. He told me that PRIMED was designed as a “military strategy” and that the programme sought to exert state control over the urban periphery to prevent leftist guerrilla groups from entering the city from its borders. He showed me on a street map, which he labelled “strictly confidential”, the location of the settlements of the three renewal areas, the movements of the guerrilla groups in the city, and how the new urban architecture would contribute to the improvement of military and police control in the upgraded settlements.

We knew that the urban peripheries were taken over by the guerrillas. […] Three districts were taken over by the guerrillas […]. We wanted to implement the programme precisely in these three districts. […]. In other words, it was a military strategy that we were considering at that time […]. The residents [of these districts] live in a borderline situation between delinquency and honesty, and this situation always has a territorial outcome. These are interstitial spaces in the city which do not belong to anybody and can easily be appropriated by the guerrilla groups. Hence, we needed a strategy for the periphery of the city […]; it is hard to govern the periphery; people who live there are unpredictable because they don't have an urban identity. They easily join the other side [the guerrillas]; thus, we needed a strategy that would give the periphery an urban identity […]. We noticed that war strategies are always being created on the edges, so what we are doing now is creating new centres on the urban periphery.25

Intrigued by the interview with the former PRIMED officer, I paid full attention to territorial markers during participant observation in the PRIMED renewal area of Comuna 6. Probably the most evident territorial expressions of the programme's (presumed) military strategy were the then newly built path galleries of reinforced concrete that followed the contours of the hillsides on which the settlements of the three renewal areas had expanded. Residents had helped to build these path galleries. They showed me how these galleries connected the settlements of their districts and how they facilitated their transit through the settlements. The former PRIMED officer traced these galleries on his “strictly confidential” map and explained that the galleries would allow the police and military forces to move quickly from one settlement to another as they connected the settlements in each upgraded district. It seemed to me that the programme's (presumed) military strategy was inscribed onto the upgraded space of the settlements and could bee literally “read” in the territory by the observer.

Graffiti in the PRIMED area of Comuna 6 also attracted my attention. It read, for instance, Fuera milicianos les desea la ley del desprecio (“Get off, militias, that is what those who despise you want you to do”) and Pero fuera milicianos. Bienvenidos militares al Picachito (“But get off, militias. Military, welcome to Picachito”). Residents in the settlements of Comuna 6 suspected that paramilitary groups, known as Convivir, entered the settlements, taking advantage of the lack of resistance resulting from the pacts of non-aggression. Created in 1994 by Colombia's Ministry of National Defense as “special vigilance and private security services”, these groups engaged civilians mainly in rural areas in fighting back against the influence of guerrilla groups. In the mid-1990s, seven Convivir were also registered in Medellín (Hylton, 2014:25; Téllez Ardilla, 1995:107). However, in the PRIMED settlements at that time, graffiti was the only territorial marker indicating the possible presence of these groups. Residents, however, felt exposed to fuerzas oscuras, “sinister forces”, which kept watch over the settlements without being visible (see Stienen, 2016:247).

It is tempting to interpret the re-territorialisation of Medellín's urban edge in the framework of PRIMED during the 1990s as counter-insurgency. In what follows, I show, however, that this interpretation is too narrow.

The 1990s can be considered an experimental period in relation to what Uribe de Hincapié (1998:17) distinguished as disputes over “just order, sovereign representation, territorial domination, institutional control of public goods, and the subjection of citizens” in Colombia. This experimental period, however, ended at the turn of the millennium. In 2012, more than a decade after the termination of PRIMED, the confessions of a paramilitary and drug trafficker, Henry de Jesús López Londoño, alias “Carlos Mario” or “Mi Sangre” (My Blood), seemed to retrospectively confirm rumours in the 1990s that PRIMED was a counter-insurgency programme. The confessions revealed that the 1995 pacts of non-aggression in Medellín, which eventually facilitated the implementation of PRIMED (and also my fieldwork in the renewal area of Comuna 6), were supported by paramilitary groups together with organised crime to prepare the ground for the paramilitary incursion in the city after the turn of the millennium with which the confessed was charged.26

Scholars have analysed the paramilitary “territorial takeover” (Franco, 2003:103) of Medellín comprehensively. It culminated in 2003 with the military offensive in Comuna 13, known as Operación Orión, ordered by far-right president Alvaro Uribe (2002–2010) in the framework of his “democratic security policy” that aimed to strengthen the activities and presence of the security bodies throughout the national territory (Giraldo Ramírez and Preciado Restrepo, 2015; GMH, 2011; Rozema, 2008; Franco, 2004; Angarita Cañas, 2003, 2008). Comuna 13 is a huge underprivileged district at the city's edge which included, among other neighbourhoods, the settlements of one of the three areas upgraded by PRIMED. The district was considered Medellín's stronghold of insurgent milicias influenced by Colombia's guerrilla groups and was turned into a showcase for urban counter-insurgency after the turn of the millennium. Commanded by Colombia's army and national police in coordination with paramilitary forces, the 2003 military offensive in Comuna 13 eventually eradicated the insurgent milicia groups in the city. After this military offensive, paramilitary groups which converged into the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC; United Self-Defence Groups of Colombia) in 1997 eventually controlled 70 % of the urban territory in alliance with organised crime. In 2003, the government negotiated a ceasefire with the paramilitary groups and subsequently their demobilisation.27

Many assume that the paramilitary “territorial takeover” (Franco, 2003:103) of Medellín made possible the city's far-reaching urban transformations and decrease in homicide after the turn of the millennium, recently coined as the “Medellín Miracle”.28 To substantiate this argument, Hylton (2014), for instance, quotes the former leader of the AUC and drug trafficker Diego Fernando Murillo Bejarano, aka Don Berna, who stressed that the paramilitaries “helped to pacify the city” and that their incursion in the city was necessary to guarantee “investment, particularly foreign investment, which is essential if we are not to be left behind by the engine of globalization” (Amnesty International, 2005, quoted in Hylton, 2014:81f). However, it would be misleading to regard the re-territorialisation within the framework of PRIMED during the 1990s as part of the paramilitary “territorial takeover” of Medellín, even though the city's mayor, Sergio Naranjo Pérez (1995–1998), contextualised PRIMED with an argument similar to that of the quoted paramilitary:

All important cities of the world are getting ready to be acquainted with the global economy with a special strategy of urban equipping, the support and incentives to profitable enterprises, the training of advanced human resources, and the international promotion of their productive infrastructure, in order to have access to international capital in their influence zone. Medellín cannot be the exception. Therefore, initiatives such as the Programa Integral de Mejoramiento de Barrios Subnormales – PRIMED, which has a preventive and integral nature […], are essential […] to firmly push Medellín towards the future (Sergio Naranjo, quoted in PRIMED, 1996:8).

Demarest (2011:10) and Ballvé (2012:612) claimed counter-insurgency operations typically entail three steps: (1) clearing a territory of insurgent groups and taking this territory back from insurgent control, (2) holding the territory by securing it with measures that include repression, and (3) building durable institutionality both in terms of physical infrastructure and territorial governance (see also Franco, 2003:105f)29. PRIMED's re-territorialisation did not follow this strategy even though the programme built physical infrastructure and state institutionality to address the root causes for the presence of insurgent groups in the settlements. The programme eventually benefitted from the pacts of non-aggression that turned out to be supported by the paramilitaries. However, it neither participated in encouraging (or concluding) the pacts, nor did it include repressive measures to clear the renewal areas from insurgent milicia groups. On the contrary, PRIMED was primarily an outcome of Medellín's civic activism during the 1990s. At the beginning of the 1990s, progressive local NGOs, grassroots organisations, academic research groups, and progressive Catholic priests, together with liberal factions of the business sector and local elites, took advantage of the new juridical and political framework established by the 1991 constitutional reform. They mobilised public debates in open forums and at Mesas de Concertación (open round tables) about the reasons of the city's violence and about alternatives to rebuild the urban social tissue. Supported by the Presidential Office for Medellín and the Metropolitan Area, these debates established a kind of Habermasian public reason in the city during the whole decade of the 1990s (see Urán Arenas, 2012; Stienen, 2005, 2009; and Betancur et al., 2001). PRIMED was designed in the context of this vivid civil activism and in the spirit of the critical self-reflexive gesture this activism incited in the city. This was the context of the above-quoted statements made by professionals who participated in the programme design.

3.3 Disputing re-territorialisation at the city's edge

PRIMED negotiated “fields of social experimentation” (de Sousa Santos, 2003:38, 285) with the residents in the renewal areas. For instance, the programme officers not only arranged their access to the settlements with the illegal armed youth groups but also debated with them the implementation of the programme. During the first years, organised residents attended programme meetings with basic PRIMED documents in hand. Due to the territorial control exercised by the armed youth milicias in the settlements, any deviation from the original objectives of PRIMED during its implementation was debated with the residents. An officer said, “If you are facing a guy armed with a gun and you are only armed with your professional knowledge, if you are not able to prove that you are right, what happens then with that gun? You pay with your life”.30 The armed youth groups, for instance, tried to blackmail the small construction firms PRIMED hired outside the settlements to execute the infrastructural works in the renewal areas. To stop this, officers in the settlements engaged these groups as security guards to watch construction sites and materials. This move was considered illegal but legitimate to ensure the programme's acceptance in the settlements. It demonstrated that the territorial authority of the illegal armed youth groups was not directly challenged by PRIMED. Thus, following the discussion of Agnew and Oslender (2010) on “disputed sovereignties”, it can be argued that the micro-territorial sovereignties established by these groups overlapped with the state territory PRIMED expanded in the settlements.

The PRIMED officers also negotiated land use with the residents. Individual land appropriation had provoked many violent conflicts in the settlements of the renewal areas before the start of PRIMED. Residents had fought hard to cut metre by metre of land off the steep hillsides to build their individual dwellings. During the upgrading process, they often resisted ceding individually appropriated land to PRIMED for the construction of public spaces in the settlements. With the construction of public space, the programme not only sought to stabilise the steep hillsides where the settlements expanded. It also aimed to implement Colombia's 1989 Urban Reform Law, which defined public space as area for “the satisfaction of collective urban needs”. This law is probably one of the most enlightened laws for public space conservation in Latin America.31 Colombia's 1991 Political Constitution made public space a constitutional right and designated public authorities as its guarantors, proclaiming that “it is the duty of the state to protect the integrity of public space and its assignment to common use, which has priority over individual interests”.32 Taking individually appropriated land from residents to expand public space or to build public facilities in the settlements was thus legitimised by PRIMED through establishing equal access of all residents to urban space. These programme goals provoked heated debates between the programme officers and the residents. Based on their technical expertise, the officers insisted on the importance of public spaces to stabilise the terrain and assert equal rights. Residents, by contrast, insisted on their empirical knowledge of the territory and sought to convince the programme officers that there was not always a need for open space. In some cases, residents engaged in these controversies only because they speculated on individually appropriating a neighbouring plot of land selected by the programme to be transformed into public space. They planned to sell the land or to expand their individual dwelling on it in order to secure their families' survival. Such controversies between the residents and the programme officers often resulted in compromises that redirected the programme's intended re-territorialisation.

The negotiation of gender relations was also part of PRIMED's re-territorialisation. Residents had to contribute unpaid work to the construction of public space. Both men and women were trained in construction work at the National Training Service (Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje, SENA), a public institution that offered vocational training programmes. In Comuna 6, men used to complain about being obliged to do unpaid work and often did not appear on the construction sites. Women, by contrast, were largely committed to free work and often assumed the responsibility for the construction sites. Due to the gender-specific impact of the armed conflict in the settlements before the start of PRIMED, women often expressed that they perceived their commitment to the programme as liberating. With the start of PRIMED their freedom of movement increased as well as the territorial radius accessible to them in the city.33 Before the start of PRIMED, women had often locked themselves in their dwellings to protect themselves and their children from the armed clashes in the settlements. They also wanted to prevent finding their self-constructed informal dwelling in the hands of another person who seized the opportunity to appropriate it even during a short absence of the de facto owner. This situation changed during the implementation of the programme. For instance, a single mother told me that engaging with the programme helped her to overcome both her spatial isolation and economic shortage as she engaged in developing a women's cooperative. Another woman whose drug-addicted husband and two adolescent children were killed in a purge by the milicias explained that her engagement with PRIMED gave her life a new purpose. She said, “If I'd continued staying locked in my shanty, I'd have gone crazy.” Other women described intra-family violence to which they were subjected because of being locked in their dwellings. They said that engaging with PRIMED meant for them leaving their dwellings and making their problems public by sharing them with other people. Moreover, they insisted that their husbands could no longer threaten them with kicking them out of the dwelling during family disputes and leaving them on the street because PRIMED transferred ownership titles to both spouses. These women argued that the ownership title helped them to secure “their right to a place”. Some of these women started building their own room after their dwellings were legalised. They stressed that each wanted a room of her own where she could “breathe” and no longer feel bullied.34

In conclusion, the re-territorialisation of Medellín's disputed urban periphery during the implementation of PRIMED had an insurgent dimension in the sense discussed by Holston (2009) and Wahren (2011). These scholars developed both a non-normative conception of “insurgence” that has no “inherent moral or political value” (Holston, 2009:35) and the idea of a “disruptive institutionality” (Wahren, 2011). My argument is that during the implementation of PRIMED, a “disruptive institutionality” emerged from the disputes between the residents and the governmental and non-governmental actors involved in the programme and coordinated by PRIMED. These disputes unsettled normative binaries such as legal/illegal, legitimate/illegitimate, public/private, and formal/informal and produced new social subject positions and political identities among the residents. Residents gained visibility in the city as subjects of law during the implementation of PRIMED. They also experienced how the PRIMED officers in the settlements prioritised technical and legal criteria in the negotiations of land use instead of arbitrarily relying on political clientele relations. This might have been why, during the 1997 mayoral elections, some residents campaigned for government programmes rather than for individual candidates who promised potential voters that they would get personal benefits for their vote, as had usually been the case.35

Nevertheless, PRIMED did not prevent the paramilitary incursion in the settlements despite empowering the residents. PRIMED's perceived strength eventually turned out to be the programme's weakness, namely the neutrality of its legalistic-technocratic approach to conflicting and antagonistic interests and territorial projects in the settlements. PRIMED did not consider that the pacts of non-aggression would “open” the settlements to other armed groups by transforming the settlements' “invisible frontiers” into “frontiers of peaceful co-existence”. The paramilitary and criminal networks, established to carry out the paramilitary incursion in Medellín, managed to penetrate these frontiers of peaceful co-existence and co-opt residents and armed youth groups in the settlements. This was all the easier given the lack of economic alternatives, particularly for youth, an issue not addressed by PRIMED. Armed youth groups and residents who resisted being co-opted were denounced and expelled, or they “disappeared” and were assassinated by the paramilitaries. During the military offensive in Comuna 13, the new infrastructure of this district's former PRIMED renewal area eventually facilitated the movements of the police and army but was also damaged during the offensive together with upgraded houses.

The consolidation of state space in Lefebvre's sense (see Brenner and Elden, 2009:364f), initiated by PRIMED at Medellín's disputed urban periphery, was eventually achieved under different auspices by the paramilitaries once they controlled the city after the turn of the millennium. Demarest (2011:9f) argues that the 2003 military offensive in Comuna 13 “permanently changed the scale and nature of the security challenge” in Medellín. PRIMED's experimental potential, identified in this article, was not sustained in the city after the end of the programme.36 PRIMED's re-territorialisation measures had consolidated citizens' “right to (urban) territory” through legalising individual property rights; registering grassroots organisations to give them a legal status and the right to public funding; formalising street numbers and addresses; and expanding public services, infrastructure, and public space. But eventually these measures had an opposite effect: under paramilitary control, they facilitated the fierce territorial rule over the residents by the police and Colombian army (see Demarest, 2011; Franco, 2003). After the 2003 military offensive in Comuna 13, police stations and/or military bases were established in the districts at the city's edge, where the three PRIMED renewal areas had been located during the 1990s.

This article observed the Latin American debate on territory through the lens of the territorial-peace approach agreed in the peace accord between the Colombian government and the FARC guerrillas in 2016. In Latin America, claims for territory as “anti-hegemonic community space” of peasant communities (ethnically and non-ethnically defined) have been central to politics of resistance and emancipation and have challenged liberal statehood. In Colombia, the politico-juridical redefinition of state space in terms of multi-territoriality was incorporated into the country's reformed political charter in 1991. Rural Afro-descendant and indigenous communities are constitutionally entitled to collective territories.