the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Between divine and social justice: emerging climate-justice narratives in Latin American socio-environmental struggles

Celia Ruiz-de-Oña Plaza

This exploratory study traces the emergence of climate justice claims linked to narratives of Latin American social movements for the defence of life and territory. I argue that in post-colonial settings, religious and historical injustices and socio-cultural factors act as constitutive elements of environmental and climate justice understandings which are grounded in territories immersed in neo-extractivism conflicts. Environmental and climate justice conceptualizations have overlooked the religious fact present in many Latin American socio-environmental movements. As a result, the intertwined notions of divine justice and social justice are unacknowledged. To illustrate this claim, I examine socio-environmental and climate justice claims in a cross-border region between Guatemala and Chiapas. This region has a common ethnic background but divergent historical trajectories across the border. Diverse nuances and intensities adopted by environmental and climate justice practices and narratives on both sides of the border are examined. The case study reveals the importance of religion as a force for collective action and as a channel for the promotion of place-based notions of climate justice. The text calls for the examination of the religious factor, in its multiple expressions, in the theories of climate and environmental justice.

- Article

(2325 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(596 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Socio-environmental struggles in Latin America are, in many cases, sustained by a formal religious faith or by adaptations of ancestral world views (Lorentzen and Salvador, 2006). However, as Kirmani (2008) has noted, the religious element is often omitted when studying social movements. The same is true of the environmental-justice literature. In contrast, the link between religion and climate change – and more broadly, between religion and environmentalism – is increasingly addressed in the environmental-humanities field (Jenkins, 2017) as well as in media and religious studies (Bergmann, 2009; Gottlieb, 2010). Thus, the diverse literature that does address the religious element confirms that, religion as a social institution plays a key role in instigating collective action and issuing justice claims based upon a spiritual and sacred notion of nature (Haluza-DeLay, 2014). That literature also examines the different approaches taken by diverse faiths when confronting environmental devastation and climate change. Among the elements problematized in that literature are religious dogma, structure, organization, and conceptions of deity and human nature (Gerten and Bergmann, 2011; Veldman et al., 2013). However, this body of research is not connected, at present, to the environmental and climate-justice conceptualizations.

Meanwhile, in the social and political sphere, claims for climate justice are increasingly shaped by dogmas of the faiths that serve social movements as channels of dissemination and sources of motivation. A notable example of those dogmas is liberation theology, of Catholic orientation (Beling and Vanhulst, 2019). Recent research into the influence of such dogmas appears to have been triggered by the debate surrounding the papal encyclical Laudato si' (published in 2015), which calls emphatically for stronger action against climate change. It prompts for a more integrative view of climate justice: one that moves away from carbon issues (Honty, 2011) and effectively links climate to cultural and symbolic factors (including those that derive from religion).

However, local congregations of different faiths can vary markedly in how they view climate-justice issues and act upon them in the light of their respective religious declarations. For example, does their understanding of those declarations impel them to action, or not? What is the relevance of their faiths to the configuration of placed-based notions of environmental and climate justice? What different expressions do those notions take, and what are the determining factors for this differentiation? In what way are environmental and climate issues being linked in specific territories? And what narratives are the people building? Exploring these questions can contribute to broadening and diversifying the notions of environmental and climate justice.

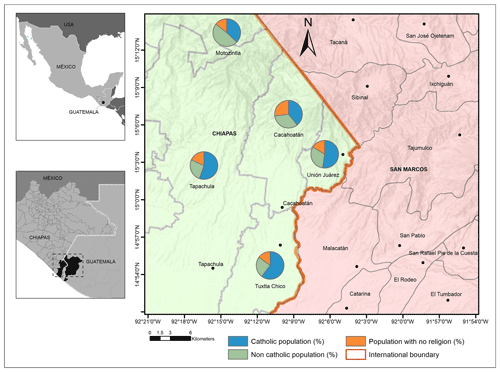

To illustrate this, I examine socio-environmental and climate justice claims in a cross-border region between Guatemala and Chiapas: the southwestern segment of the 1000 km border strip, in the Mam ethnic territories bordering the Tacaná volcano area (see Fig. 1). This region has a common ethnic background but divergent historical trajectories across the border. Religion occupies a central role as an organizing institution in social life, as well as in resistance struggles. There are several religious faiths present on both sides of the border (see Fig. 1). However, not all of them lead to environmental anti-capitalist activism. Those involved with liberation theology are configuring demands for environmental justice which are conceived as struggles for the defence of territory and for the right to political autonomy of indigenous peoples. Within this framework, a place-based notion of environmental justice is constructed, one that is anchored in socio-environmental conflicts and rooted in cultural ways of understanding the territory.

In recent times, mentions of climate change in connection with the impacts of neo-extractivism are increasingly common in the narratives of socio-environmental movements operating in this cross-border region. The article looks at two socio-environmental movements: the Movement for the Defence of Life and Territory (MODEVITE), on the Mexican side (Table 1), and the Maya Mam, Te Txe Chman council, on the Guatemalan side (Table 2).

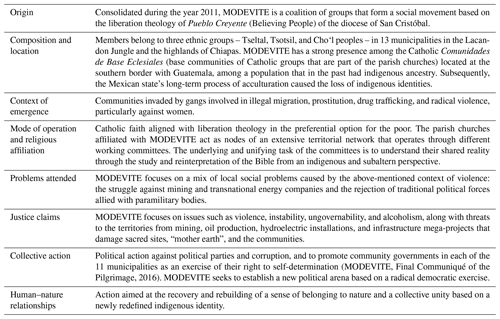

Table 1Characteristics of the Movement for the Defence of Life and Territory (MODEVITE): Chiapas.

Source: prepared by the author based on dispatches, news, and posts from https://modevite.wordpress.com/2019/08/21/comunicados/ (last access: 15 August 2020) and https://sipaz.wordpress.com/2019/08/21/chiapas-megaperegrinacion-del-movimiento-en-defensa-de-la-vida-y-del-territorio-modevite-en-tuxtla-gutierrez/ (last access: 15 August 2020).

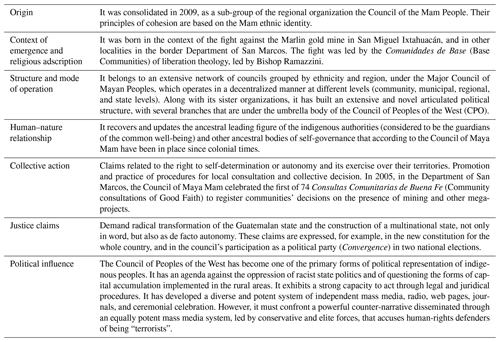

Table 2Characteristics of the Council of Maya Mam, Te Txe Chman, Guatemala, Department of San Marcos:

Source: prepared by the author based on dispatches, news, and posts from https://www.prensacomunitaria.org/category/territorios/suroccidente/san-marcos/ (last access: 17 August 2020), https://cpo.org.gt/2019/?cat=43 (last access: 17 August 2020), https://cpo.org.gt/2019/?p=28 (last access: 17 August 2020), https://movimientom4.org/tag/consejo-del-pueblo-maya-cpo/ (last access: 17 August 2020), https://movimientom4.org/2016/10/declaracion-de-la-asamblea-nacional-del-consejo-del-pueblo-maya-cpo/ (last access: 17 August 2020) and http://consejodepueblosdeoccidente.blogspot.com/ (last access: 17 August 2020).

I hypothesize that the religious – primarily, but not exclusively, liberation theology – is driving the emergence of climate justice narratives in these socio-environmental movements, hand in hand with the encyclical Laudato si'. From here, incipient claims of climate justice linked to territory, culture, and politics are arising. The case of this cross-border region illustrates this process. On both sides of the border, the churches spread and generate awareness of climate justice. However, divergent historical trajectories and the unequal presence and action of the nation state give rise to practices and narratives of religion and climate change of varying intensity across the border.

In this light, the objective of this paper is to highlight the need to update and complement the literature's present notions of environmental and climate justice, specifically by including elements such as religious motifs as fundamental elements of future justice conceptualizations. The role of those elements might be demonstrated by treating instances where they support and interact with historical and social-justice claims in territories with a colonial legacy (Álvarez and Coolsaet, 2018). I conclude by noting that this region's contingent particularities provide an opportunity to broaden and enrich the conceptualizations found in the literature.

Figure 1Location of the Maya Mam cross-border area in the southern section of the border of Chiapas and Guatemala. The map details the composition of the religious diversity of the municipalities on the Mexican side (there are no disaggregated data for the municipalities of San Marcos, Guatemala). Prepared by Yair Merlin. Source: INEGI, 2010. National Population and Housing Census 2010. National Institute of Statistics and Geography. Aguascalientes, Mexico. Consulted in July 2020. Available at https://www.inegi.org.mx/temas/religion/ (last access: 15 July 2020).

Throughout Latin America, protests are surging in response to the social and environmental impacts of infrastructure mega-projects, the expansion of non-traditional agricultural exports, and extractive industries such as mining or hydroelectricity. In this context, impacts of climate change are intensifying. They are also interacting with the effects of this wave of neo-extractivism. Quite often, the resulting social mobilizations become transnational via a diverse network of 70 organizations, ranging from traditional campesino unions and indigenous groups to urban environmentalists. As the need arises, organizations in that network create ad hoc fronts to support specific struggles.

At the heart of the overarching social unrest lies an active and visceral rejection of the necropolitics and necroeconomics of the current capitalism phase (Mbembe, 2003). Sometimes known collectively as the “politics of death”, this politico-economic subjugation is particularly intense in Latin America, where it is implemented by right-wing and left-wing governments alike (Botero and Galeano, 2017). According to African scholar Achille Mbembe, the politics of death result in human rights violations (Bastos and de León, 2014; Navarro, 2013; Sosa and Camey-Huz, 2015), as well as ecological devastation and the exclusion of entire populations that are considered superfluous to the production system (Mbembe, 2003).

Social movements are responding to this context by reconfiguring themselves under the banner of socio-environmental struggles. These movements call for political autonomy, radical democracy, the right to be consulted, and the right to decide the destinies of their own territories. A common narrative unifies socio-environmental struggles of many forms and tendencies under the banner of the defence of life and territory. The critical axis of this narrative is constructed against hegemonic territorialities that neglect other forms of being, in favour of a new relationship between the non-human and the human world. That relationship includes the emergence of new ontologies of being more than human (de la Cadena, 2010; Escobar, 2014), along with other rationalities not based on the neoliberal rationale. Also included is the articulation of a range of actors across different scales of collective action. Regarding science, this new relationship would promote alternatives to the dominant narratives of scientificism. In summary, this relationship calls for a new language of valorization that would both supersede the coloniality of knowledge (Mignolo and Escobar, 2013) and create new meanings that amplify the dimensions of life instead of reducing it to a narrow productivity rationale. That rationale emphasizes the politics of racialization, as well as the collective transgenerational psychological and subjective marks of submission still operating in post-colonial contexts (Álvarez and Coolsaet, 2018). In territories where the colonial legacy left an imprint of a sense of subjugation, psychological processes cannot be detached from the structural: both are relevant to understanding how socio-environmental struggles emerge and unfold. Coloniality anchors a racial ideology in the psychological structure of the oppressed peoples who have been targets of domination strategies in Latin America (Grosfoguel, 2011). Therefore, the transformation of objective conditions is, by itself, as insufficient as the transformation of only the subjective sphere (Álvarez and Coolsaet 2018).

The innovative collective action described above has been labelled the “eco-territorial turn” – a term coined by a group of Latin American socio-environmental thinkers (Alimonda, 2011; Leff, 2014; Svampa, 2019). The territory is understood as the result of the interaction of its environmental, material, social, cultural, and symbolic dimensions. Of these, the spiritual/religious dimension is often highlighted in territories with an indigenous presence (Paz-Salinas, 2017). These characteristics give specificity to the notion of environmental justice in Latin America. There is, however, a key element that is often overlooked in the literature on the defence of life and territories: the religious sentiment that underlies a significant portion of the struggles, especially in territories of predominant indigenous and campesino identity.

Because scholarship in the field of environmental justice was built predominantly upon studies of western environmental conflicts, it falls short of grasping the Latin American specificities detailed in the previous section. For that reason, critical scholars call for decolonizing environmental-justice studies (Álvarez and Coolsaet, 2018). According to these thinkers, the uncritical use of western conceptualizations to analyse non-western environmental-justice conflicts can reproduce environmental injustices. In post-colonial settings, the environmental component has not been the decisive argument for justice claims, despite its obvious relevance in structuring narratives of defence of life and territories.

Previous studies, including recent environmental-justice scholarship conducted in Latin American scenarios (Carruthers, 2008; Hafner, 2018), have emphasized that environmental concerns cannot be detached from popular mobilizations for social justice and equality (Carruthers, 2008:9, 12). Furthermore, recent scholars' definitions of environmental justice have superseded earlier perspectives, which focused narrowly upon distributional aspects. The new definitions, which have become common in the literature, are more integrative and inclusive and call for a more explicit conceptualization of how justice is understood (Pellow, 2017; Schlosberg, 2009). To that end, Schlosberg argues for a broad, pluralist notion of justice that encompasses the human and the non-human world (Schlosberg, 2009:5). He also acknowledges the importance of having a multiplicity of justice notions that coexist at the individual and collective levels and which include not only distributional issues but also recognition, participation, and functioning (Schlosberg, 2009:4).

Hafner (2018) proposes an innovative framework, based on revealing local structures and elements of thought style, for analysing environmental justice in temporal and spatial contexts (Hafner, 2018:3). The proposed framework allows for the identification of local concerns and claims. Such an approach may enable researchers to understand which grounds local people invoke (or not) in their claims of justice. It can also reveal the importance of pre-conflict stages and why open conflict does or does not result (Hafner, 2018:2). Hafner's emphasis on the epistemology of cognition, particularly the visceral cognitive elements thereof, opens a new horizon of analysis: one that makes room for the interconnectedness of the rational and the emotional (Hafner, 2018:232). Hafner's work is only one example of recent conceptual developments in environmental-justice theory that would be particularly relevant when representing the complex Latin American socio-environmental struggles as a majoritarian expression of resistance. However, environmental-justice theory still needs to incorporate the religious dimension that animates most of these struggles.

In the work reported in the present article, I follow a narrative approach to analyse qualitative data under an interpretative paradigm. By using the term narrative, I follow Riessman (2008) in meaning the elaboration of stories that function as devices through which the actors position themselves and attribute specific ideas of “responsibility”, “guilt”, “victimization”, “urgency”, “disaster”, “the rational”, or “valid behaviours” in statements located temporarily and spatially. These statements can be oral, written, or graphic about a vital experience or conjunctural event (Arnold, 2018). During the personal or collective process of constructing the narrative, identity elements of a historical nature come into play (Tamboukou, 2013) to promote mobilization for social change, or to invite audiences to enter the perspective of the storyteller (Elliott, 2005). Analytically, I follow Riessman in “[examining] primarily what content a narrative communicates, rather than how a narrative is constructed […] by examining how stories of resistance generate collective action in social movements” (Riessman, 2008:73). The narrative analysis that I present was based upon secondary sources obtained from dispatches, notices, political manifests, and alternative-press news that served communicative and political purposes. I also interviewed the Guatemala coordinator of the Global Catholic Climate Movement. The narrative threads identified in those documents and interviews allowed me to access the socio-environmental movements' notions of environmental justice and to identify emergent climate-justice claims. Also included are observations about the transborder region of the Tacaná volcano during the municipal and presidential electoral campaign in the Guatemala municipality of Sibinal, in the Department of San Marcos.

As in the case of environmental-justice conceptions, dominant conceptualizations of climate justice do not contemplate the effect of religious feelings in calls for climate justice. Instead, research has employed a philosophical and ethical perspective that focuses upon the just distribution of burdens and entitlements and upon the differentiation of responsibilities in the realm of adaptation and mitigation (see Harris, 2019). In the international political arena, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) enunciated the principle of “shared but differentiated responsibilities”. That principle established the need to create specific funds to finance the adaptation efforts of developing countries (Honty, 2011). Historical emissions of developed countries have been at the centre of a polemic debate between developed and developing countries. Honty rightly points to the incontrovertible fact that climate change will take place in an unequal world. Present inequalities will, on the whole, grow as the impacts of climate change increase (Honty, 2011:19).

In Latin America, calls for justice as recognition of historical responsibility, and not only as a fair distribution of burdens and costs, can be identified in arguments made by countries such as Bolivia. On this matter, Forsyth (2014) points out the need to reassess justice frameworks that are based upon distribution approaches. That reassessment would allow for a wider range of solutions. He also advocates Sen's approach to justice as a means of moving beyond dichotomies based upon distributional and procedural justice, and thereby initiating a more open and inclusive debate about risks and solutions.

In general, the limited achievements of international climate negotiations have left researchers with a sense of failure and mistrust. As a result, researchers now pay more attention to other sources of motivation for action. Among these, religion seems to be gaining unusual strength in the realm of climate justice.

4.1 The religious and climatic elements in MODEVITE and the Council of Maya Mam narratives of struggle

In liberation theology, and specifically in the encyclical Laudato si', climate justice is considered an ethical imperative. The encyclical points directly to the need to base international mitigation policies upon principles of climate justice (Kerber, 2010). It reacts against the mercantilist and instrumental rationality of the present policies, from which the human and ethical dimension is absent. Along somewhat similar lines, recent developments in Latin American liberation theology (see Boff, 2011) incorporate a renewed theology of creation, along with the Latin American ecofeminist perspective and the development of an indigenous theology (Kerber, 2010). Laudato si' integrates these developments to build a critique that attacks the pillars of the current economic system. The encyclical's goal of radically transforming the paradigm of modern civilization entails a reconstruction of the human–nature link. The subtitle of the encyclical (“On Care for Our Common Home”) synthesizes the integration and belonging of the human in nature. The following insights about the encyclical's bases and goals are offered by Efraín Bámaka, who is a certified animador (local promoter) of Laudato si' and coordinator of the Guatemala chapter of the Catholic Climate Movement, as well as a researcher at the Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala:

(…) in paragraph 51 it is mentioned that “inequity does not only affect individuals but entire countries” there it speaks and forces us to think about ethics of international relations, because there is a real ecological debt, and here what I want to mention (…) is particularly between the north and the south, related to trade imbalances, with consequences in the ecological field as well as the disproportionate use of natural resources historically carried out by some countries. And then it comes to talk about exports, that is, it is a document that from a socio-political analysis, talks about and even goes beyond climate justice, which it does mention: we need a cultural revolution (EBL, Huehuetenango, 30 June 2020).

But how do social movements incorporate these tenets into the daily struggle for environmental and climate justice in unique territories? In the borderlands of Chiapas and Guatemala, two key socio-environmental movements have been leading the fight for environmental justice in the context of confrontations with international mining exploitation. The first movement is the Council of Maya Mam Te Txe Chman, an ancestral governing body of the Maya Mam people of the San Marcos department, Guatemala (see Table 2). The second is the Movement for the Defence of Life and Territory (MODEVITE), a coalition of catholic indigenous organizations with a presence in some territories of Chiapas. Both movements draw upon liberation theology but incorporate climate justice in a differentiated manner and with variable intensity throughout the borderlands. Those lands, which are part of the ancestral territories of the Mam Mayan ethnic group, extend over a portion of the cross-border area between Chiapas and Guatemala. The Tacaná volcano area, which straddles the border, is significant because of the contrasting degrees of environmental conflict and struggle experienced on the two sides.

The shared colonial past of this region includes marginalization, exclusion, violence, and the imposition of the Catholic religion. Even today, half of the region's inhabitants are professing Catholics. (See Fig. 1; no disaggregated data are available for Guatemala.) However, religious diversity is now evident in this region, as well as throughout Guatemala and Chiapas (which is Mexico's most religiously diverse state). Protestant denominations of quite varied creeds have a significant presence, with evangelical and neo-Pentecostal religions predominating. The church of liberation theology is a prominent feature of the religious profile throughout this transboundary region.

Both the Council of Maya Mam and MODEVITE (see Tables 1 and 2 for descriptions) are community-oriented movements that use religion as a means of community development “to improve the well-being of a community, often in the face of a repressive government” (Kirmani, 2008:29). Kirmani remarks that although religious feelings are an important factor in mobilizing collective action (Kirmani, 2008:33), the acts of resistance and improvement of well-being are varied and are not restricted to the celebration of the faiths. A particularly relevant example is the improvement of agricultural systems from an agroecological perspective. Nevertheless, for MODEVITE as well as the Council of Maya Mam every action, resistance, and confrontation rests upon a religious sentiment. MODEVITE provided a clear example of this through the communiqué that it read to the public during MODEVITE's pilgrimage of 20 August 2019. In that communiqué, the sacred dimension of both the protest and its content is manifest. The communiqué alludes to the belonging of the Believing People to mother earth as the source of the people's primary nourishment. The communiqué also invokes a timeless dimension that lives in the memory of the ancestors. The circular temporality expressed here is one of life and death in the continuous rebirth of nature. In contrast, the survival of capitalist production is conditioned by the constant growth conceived from a linear temporality. As the communiqué explained,

we have gone out again to walk and to speak our word; we are of the original peoples with a face and a heart of our own, born of Mother Earth and corn, with a spiritual relationship woven into life and territory. In this way we remember the memory of our grandmothers and grandfathers: we are earth, we are fire, we are air, we are defenders and caretakers of Mother Earth (https://modevite.wordpress.com/2019/08/21/comunicados/, last access: 29 December 2019).

The religious adherence of the Mexican movement MODEVITE is exclusively to the Catholic faith based on liberation theology. In Guatemala, the Council of Maya Mam, too, emerged from the church of liberation theology. However, the council now gives greater weight to the Mam ethnic identity than to religious affiliation. As a result, the council has greater religious diversity than MODEVITE. Some council members have no defined religion. Nevertheless, the council's identification with the church of liberation theology remains strong, and some of the council's most emblematic leaders are also community leaders in the ecclesial base communities (EBL, coordinator of the Guatemala Chapter of the Catholic Climate Movement and animator Laudato si', Huehuetenango, Guatemala, 30 June 2020). Ancient Maya Mam beliefs are an additional religious element in the council; the recovery and re-creation of those beliefs plays a vital role in the upper ranks of the council's intellectuals (Consejo del Pueblo Maya, 2019:6–7).

In both MODEVITE and the Maya Mam council, women play a vital and decisive role as drivers of collective action. Strong organizational ties based on ethnic and religious adscription give way to an innovative mechanism of self-governance and self-representation in both movements. Each has a communal structure of authorities: “Consultas de Buena Fe” in the case of the council and the constitution of “plurinational community governmental bodies” in MODEVITE (see Tables 1 and 2). The political strength of these structures has shown itself in socio-environmental struggles against mega-projects.

4.2 Climate-justice narratives emerging in MODEVITE and the Council of Maya Mam

The two movements differ in the degrees to which they refer to the climate justice that was proclaimed in the encyclical Laudato si'. MODEVITE makes no specific mention of climate change in the pronouncements and communiqués that it has issued in the context of its struggle. In contrast, the Council of Maya Mam, in association with its sister organizations, is gradually inserting allusions to climate change in its manifests and public statements. (See for example Prensa Comunitaria Km. 169.) The council's sister organizations include councils of various ethnic identities, as well as a range of social organizations fighting for the defence of life and territory. A prominent example is the peasant workers' movement of San Marcos. References to climate change appear in the council's communiqués that address the violent reality that confronts its members. The communiqués denounce extractive enterprises; condemn the mining companies' expulsions, land-grabbing, and environmental damage; demand the release of political prisoners; and seek justice for victims of murders and human-rights violations.

The council also referred to climate change, albeit indirectly, when it joined several indigenous organizations in supporting the Food Sovereignty Network's communiqué entitled “Climate Change and Mega-crops also threaten our food sovereignty and the human right to food” (issued 21 September 2015). The communiqué's narrative reveals how climate change, in the context of the struggle of socio-environmental movements in Guatemala, is linked to the extractive industry and its impacts on social and environmental issues. The narrative also relates the intensity of systemic violence in the border territories of San Marcos. Going far beyond the carbon accounting that is so prominent in international politics, the communiqué alludes to the effects of climate change upon human rights and vital needs like food sovereignty. In short, the tone of the narrative that the communiqué constructs around the impacts of climate change is markedly condemnatory – a striking contrast to the logic by which international climate-mitigation policies operate. Moreover, the condemnation is accompanied by a demand for social justice, for respecting human rights, and for the protection of nature (which is always referred to as mother earth).

The Council of Maya Mam works in partnership with organizations such as the nongovernmental organization (NGO) “Commission for Peace and Ecology” (in Spanish, the COPAE). COPAE is dedicated to conducting research on local realities, to training, and to dissemination of knowledge about sustainability, justice, environment, and ecology. COPAE's outreach is a source of information for communiqués and public proclamations. Significantly, for our purposes, COPAE is also a source of information for the teachings carried out in ecclesial communities to which many grassroots members of the Council of Maya Mam belong. From the local parishes in alliance with COPAE, a path emerges for local understandings of the impacts of climate change and of how the configuration of those impacts is a question of justice in terms of a north–south debt. These understandings are always balanced with the local communities' most pressing matters:

the idea was that we have elements for the struggle that emerged from the investigation, so perhaps that's why you begin to notice certain words, certain discourses that are more formed or that epistemically go beyond mere experience and that even have in their language some epistemic notion, because they already speak to you about these questions as well (EBL, Huehuetenango, 30 June 2020).

The channelling of Laudato si' climate-justice proposals to the ecclesial grassroots communities is progressing gradually, and according to the increasingly felt effects of climate change:

(…) as a result of this question of the encyclical, the discourse on climate justice is present, but I feel that it is still a great absence, why? Look when you go to the border to these territories of San Marcos, because the people have been affected, the people talk to you about climate justice, even generational justice, but if you come to the central plateau, climate change and the environment does not mean anything to the people, because they feel that it does not affect them; instead, the people of San Marcos are affected because the mine was there, where the gold was taken from their land, where the water was stolen from their land, so, those people have already taken a stand on that discourse (EBL, Huehuetenango, 30 June 2020).

4.3 Two countries, one ethnic origin: the ancestral territory of the Maya Mam between Chiapas (Mexico) and San Marcos (Guatemala)

The region of study, which was once an ecological and cultural unity, is now divided by the international border that slices through the very peak of the Tacaná volcano. Different fates awaited the Maya Mam people who found themselves living on opposite sides of this line, which was drawn through their ancestral highland territory (Toledo Pineda and Coraza de los Santos, 2019). The region provides contrasting scenarios concerning the presence and intensity of socio-environmental struggles. The contrasts reveal how specific types of state regimes shape socio-environmental struggles in a particularized manner.

During the late 19th century, Mam people on both sides of the border were forced to work as peons in the system of fincas – coffee plantations owned by European and North American nationals. Later, the Mexican revolution and ensuing agrarian reform enabled descendants of Maya Mam peons in Mexico to hold lands communally, as ejidos. Land for that purpose was granted in the 1930s, during the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas (Hernández Castillo, 2012). This region was privileged during Mexico's agrarian reform: most of the privately owned coffee lands were transferred to groups of landless peasants, who were primarily ethnic Mam people of Guatemalan nationality. In the Mexican part of the region of study, the long shadow of the revolution – agrarian reform, plus a state where paternalism still thrives – has produced state–campesino relationships quite different than in neighbouring Guatemala.

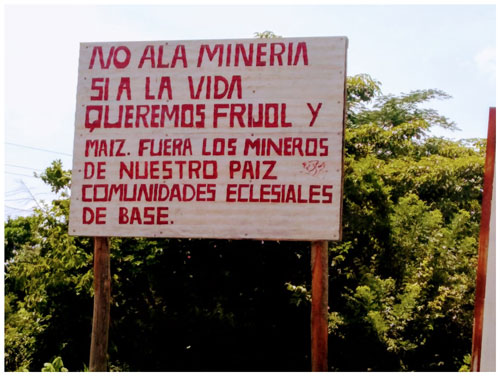

Although the defence of life and territories motto is proclaimed widely in communities on both sides of the border, the communities' experiences with extractive industries in this region are quite different across the border. San Marcos in Guatemala is an emblematic territory in the struggle against mining companies – and especially against the Marlin gold mine. The struggle is led by prominent members of the liberation theology church, such as Bishop Ramazzini. In contrast, the presence of mining companies has not been so intense in the Mexican part of the Tacaná. Nevertheless, small conflicts have occurred, especially within the Tacaná Biosphere Reserve, where various interests have prospected for ore deposits and attempted to install a micro-hydroelectric plant. These conflicts caused an explosion of support for MODEVITE in 2015–2016 (field observations and informal conversations with communal authorities of the Chespal community in Tacaná, September 2016, April 2019). More generally, communities on the Mexican side work hand in hand with the ecclesial base communities and adhere to the justice claims of MODEVITE to fight against mega-infrastructure and energy projects.

Figure 2MODEVITE placard on the southern border of Chiapas, rejecting mining in the area: “No to mining, yes to life. We want beans and corn. Get the miners out of the country”. Ecclesial communities of the base. Municipality of Chicomuselo, border with Guatemala, 30 July 2017. Photograph taken by the author.

On the Guatemala side of the Tacaná volcano region, in the Department of San Marcos, the Council of Maya Mam has a strong presence throughout several municipalities. Socio-environmental struggles occur within an exacerbated context of repression and lack of democratic guarantees (Consejo del Pueblo Maya, 2014, 2019; Rivera, 2016). The oligarchical state has never acceded to a redistribution of power and wealth, nor did it vanish after the 36-year civil war. Even now, in post-conflict times, the Guatemalan state remains a racialized discriminatory regime, as is made evident by the highly unequal distribution of land (Granovsky-Larsen, 2019). In these struggles, representatives of the church of the theology of liberation were vital to shaping the battle and organizing the people via grassroots communities. As a result, the communities' relations with the state have configured a different political arena for socio-environmental activism. A critical feature of the political context is the co-opting of movements by a network of historical and newly emerging economic elites of the state apparatus.

In addition, illegal violence is used against human-rights defenders, independent judges, and anybody opposing the elites' power (Aguilar-Støen and Bull, 2016). Food security and sovereignty are seriously jeopardized by extreme poverty, the highly uneven distribution of land, and the ongoing 4-year drought in key agricultural areas of the country (Orgaz, 2019). In this context, the Council of Maya Mam struggles not only for the defence of water, land, and territories, but also to build a new state: one that is “inclusive of all of the Guatemalan peoples, independently of ethnicity, religion or political ideology, a state that acknowledges unity in the diversity” (25 March 2019, Meeting of the Convergence Party, the new political party emerging from the Consejo Mayor Mam and the Consejo de Pueblos de Occidente, Sibinal, Department of San Marcos).

Returning to the Mexican side of the region, we see an intertwining of religious and patriotic sentiments in MODEVITE's protest marches, which MODEVITE refers to as “pilgrimages” (a religious term). Patriotic symbols of Mexican iconography like the national flag fly over the marches alongside representations of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Other religious symbols appear as well, and some of the priests who participate wear indigenous motifs on their clothes. MODEVITE questions the Mexican state but still considers it to be a reference point and a valid interlocutor. Even on MODEVITE's website, praise for Jesus is combined with that for Emiliano Zapata, an iconic figure of the Mexican revolution and the neo-Zapatism: “Viva Jesús! Viva Zapata!”.

In stark contrast, the Council of Maya Mam sees nothing to exalt in Guatemala's national past. The council identifies the Guatemalan state clearly as the critical source of oppression against the Mam people and the main party responsible for the devastation of their territory. Thus, the transformation of the Guatemalan state in its historical and current conformation is the ultimate objective of the council's struggle:

there is a document called the Political Constitution of the Mam People, and even I worked on that constitution. (…) we received a lot of criticism because how is someone going to make a constitution? Because there is only one constitution, that of the country. But no, they come and work and say this is our constitution. It's a document from October 2018. In the first chapter, first section, it says, “We stand at the side of all the struggles that seek a radical reorganization of the State of Guatemala” (…); when they refer to the State of Guatemala it is in small letters, and from there it is an interesting question, both in writing and in speech. In that sense, the Mam people see the State as their oppressor (EBL, Huehuetenango, 30 June 2020).

In local territories crisscrossed and lacerated by neo-extractivism, the religious feeling emanating from liberation theology provides a sense of strength, union, and transcendence that counterbalances the power wielded by the state in coalition with mining and agro-industrial empires. This is especially true for San Marcos, Guatemala, where the state still refuses to recognize the most basic rights of the majority of its population. Instead, the state's policies of marginalizing and slowly exterminating ethnic identities continue uninterrupted. Therefore, as indicated by the drafting of the above-mentioned political constitution of the Mam people, the Council of Maya Mam aspires to a fundamental transformation of the country. In the new Guatemala, the Mam would have rights as a nation within the framework of a plurinational state governed by the rule of law.

Meanwhile, the church of the poor of liberation theology and the narrative of “The Care of the Common House” are playing a leading role in defining a concept of climate justice that matches the interests of local populations. Liberation theology provides a sense of justice anchored not only in the here and now, but also in the recognition of a circular temporality that binds together past, present, and future generations. These aspects of liberation theology are evident in efforts by the church of the poor of liberation theology to build and disseminate claims to social, environmental, and climate justice. The church incorporates Indian theology and a blend of ancestral knowledge and scientific research, while the church's reticular organization reaches out to remote villages and municipal capitals through parishes and their grassroots groups.

Recent international research on environmental justice has evolved towards understanding the integration of sensory, emotional, and instrumental motivations. However, the experience of socio-environmental struggles in Latin America reveals the need to pay attention to the religious dimension that is present in notions of environmental and climate justice. In the context of those struggles, the idea of environmental and climate justice goes beyond the dimensions of participation, distribution, functioning, and recognition: it rests on a sense of historical grievance and is supported by intense religious feeling.

The intensities of these historical and religious sentiments are different on the two sides of the cross-border region of study because of divergent relations – past and present – with the respective figures of the state. The notion of climate justice has not been fully developed within the local bases of MODEVITE or in the Council of Maya Mam. However, that notion is increasingly incorporated in the council's declarations, communiqués, news, and proclamations of struggle. From these communiqués, a notion of multi-scale climate crisis emerges. On the one hand, the crisis is understood on a global scale as affecting the entire human brotherhood as part of the planet, along with all our fellow inhabitants of the “common house”. At the same time, the crisis is local, with concrete and differential expressions in the territories affected by neo-extractivism and the impacts of climate change. This idea of climate justice cannot be conceived in isolation from the demands for social justice, which invoke the long history of grievances and violations of human rights against indigenous communities. Hence, the notions of environmental and climate justice cannot be understood in a standardized way: they emerge from the experience of struggle in territories crossed by a complex set of historical and present causes. A fundamental dimension in new environmental-justice reformulations is the realization that Latin American socio-environmental struggles are, in many cases, of an ontological nature (Blaser, 2009). That is, they are a fight both for life itself and to give life a new and deeper definition. These new formulations can serve very different contexts, in late modern societies as well as in locations with a colonial past.

How might definitions of environmental justice incorporate the ontological nature of environmental struggles along with the intertwined structural and subjective dimensions? The environmental-justice field must explicitly consider the socially constructed nature of “environment” and “justice”. The meanings of these notions differ among cultures and political contexts because those meanings are mediated for the direct emotional, symbolic, and social experience and attachment to the territories from which they emerge (Narchi, 2015). Thus, the meaning of environment cannot be restricted to the narrow concept of a biophysical entity detached from the social sphere. Accordingly, a variety of rationalities give rise to notions of justice and nature that are distinct, in different degrees, from westernized perspectives (Álvarez and Coolsaet 2018).

The Laudato si' aligns well with the suggested broadenings of perspectives and meanings: it advocates for integrating the reformulation of the current techno-science of climate policies with cordial, emotional, and visceral rationality (Boff, 2019:6). Thus, the encyclical is also in tune with Mbembe's critique and with Hafner's proposal about the inclusion of the sensorial in the conceptualizations of environmental justice. The importance of such proposals is made clear by the concrete experiences (e.g. those presented here) of social movements that have strong components of indigenous and religious identity. Within the narratives of these movements, elements of modern and traditional combinations of rationalities can configure environmental- and climate-justice claims that depart from idealized pictures of the noble savage.

A further example of combining modern and traditional rationalities is seen in the indigenous movements' struggles for the right to constitute their own authorities (rather than have them imposed by the state). That right, which plays a vital role in the Latin American context, is based on ancestral imaginaries. However, the movements' purpose in struggling for that right is to be able to redefine the desired type of modernity in their own terms. Thus, the movements are spaces for decision and collective action that constitute true references for the enunciation of place-based notions of environmental and climate justice. Social and environmental climatic justice is strongly influenced here by the reflective and transforming practice of liberation theology (thinking–judging–acting). Within that practice, social movements find a source of legitimacy: justice with a transcendental dimension, instead of one that is disjointed from social and environmental justice in the here and now. The multiplicity that is present in that dimension needs to be part of environmental-justice definitions. Being aware of that range of different meanings opens the possibility of a real dialogue. On the contrary, taken-for-granted conversations conducted under the belief or supposition of a common understanding of uncritically assumed concepts will sap the power and creativity that we need for a battle in which we, as humanity, have no way out.

The data from this research are largely of an ethnographic nature and are not publicly available for the following reasons: the field observations, informal conversations, and ethnographic records were entered into a largely undigitized field diary; they are part of broader ongoing research that addresses other issues, particularly related to coffee, and were recorded following ethical considerations of privacy and anonymity when requested; and the transcripts of interviews conducted and their recordings were made with the consent of the individuals interviewed to maintain their privacy and in some cases may contain sensitive information that the interviewee requested not to be disclosed. For interviews with the name of the interviewee visible, the transcript may be shared as long as permission is sought from both the interviewee and the researcher. Secondary data from websites and statistical censuses are of a public nature and accessible to anyone.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-75-403-2020-supplement.

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

My deepest thanks to the people of Sibinal, San Marcos, and Unión Juárez for sharing their lives and giving us shelter and for their friendship. Special thanks to Efraín Bámaca López, for sharing his knowledge, and to Yair Merlín Uribe for the realization of the religious distribution map and for the religious tabulations. I am also grateful for the comments made by the three anonymous reviewers.

This paper was edited by Jonas Hein and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Aguilar-Støen, M. and Bull, B.: Protestas contra minería en Guatemala, Anuario de Estudios Centroamericanos, 42, 15–44, 2016.

Alimonda, H. (Ed.): La naturaleza colonizada: ecología política y minería en América Latina, 1. ed., Ediciones CICCUS: CLACSO, Buenos Aires, 2011.

Álvarez, L. and Coolsaet, B.: Decolonising Environmental Justice Studies: A Latin American Perspective, Capitalism Nature Socialism, 31, 50–69, https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2018.1558272, 2018.

Arnold, A.: Climate Change and Storytelling: Narratives and Cultural Meaning in Environmental Communication, Springer Nature, Switzerland, 2018.

Bastos, S. and de León, Q.: Dinámicas de despojo y resistencia en Guatemala. Comunidades, Estado y empresas, Colibrí Zurdo, Serviprensa, Guatemala, C.A., 2014.

Beling, A. E. and Vanhulst, J.: Desarrollo non sancto: la religión como actor emergente en el debate global sobre el futuro del planeta, 400 Siglo XXI Editores, Ciudad de México, Mexico, 2019.

Bergmann, S.: Climate Change Changes Religion: Space, Spirit, Ritual, Technology – through a Theological Lens, Studia Theologica, Nordic Journal of Theology, 63, 98–118, https://doi.org/10.1080/00393380903345057, 2009.

Blaser, M.: Political ontology: Cultural Studies without “cultures”?, Cult. Stud., 23, 873896, https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380903208023, 2009.

Boff, L.: Lo esencial del Evangelio, lo nuevo de la ecoteología: qué aporta el cristianismo a la humanidad en esta fase planetaria, Nueva Utopía, Madrid, Spain, 2011.

Boff, L.: Prólogo, in Desarrollo Non Sancto. La religión como actor emergente en el debate global sobre el futuro del planeta, edited by: Beiling, A. E. and Vanhulst, J., Siglo XXI Editores, Ciudad de México, Mexico, 7–12, 2019.

Botero, D. I. R. and Galeano, C. A. P.: Territories in Dispute: Tensions between “Extractivism”, Ethnic Rights, Local Governments and the 410 Environment in Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru, in Alternative Pathways to Sustainable Development: Lessons from Latin America, edited by: Carbonnier, G., Campodónico, H., and Tezanos Vázquez, S., 269–290, Brill | Nijhoff, Leiden, the Netherlands, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004351677_013, 2017.

de la Cadena, M.: Indigenous Cosmopolitics in the Andes: cosmopolitics in the Andes: Conceptual Reflections beyond “Politics”, Cult. Anthropol., 25, 334–370, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1360.2010.01061.x, 2010.

Carruthers, D. V.: Popular environmentalism and social justice in Latin America., in Environmental justice in Latin America: problems, promise, and practice, edited by: Carruthers, D. V., MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, 2008.

Consejo del Pueblo Maya: Un nuevo estado para Guatemala., Proyecto Política, CPO, Guatemala, available at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B31fnGLtBsbMLWR1ZkdrX3A0MWc/view?fbclid=IwAR1r3rebSoTp28Yn-5p1WAgS8o1n97Wzbrk0cOMmZr__MEpMmmhvbPbyuPU (last access: 2 April 2019), 2014.

Consejo del Pueblo Maya: Articulación política del Pueblo Maya., CPO, Guatemala, available at: https://cpo.org.gt/2019/conocenos/, last access: 12 April 2019.

Elliott, J.: Using Narrative in Social Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, SAGE Publications Ltd., London, UK, 2005.

Escobar, A.: Sentipensar-con-la-tierra. Nuevas lecturas sobre desarrollo, territorio y diferencia, Ediciones UNAULA, Medellín, Colombia, 184 pp., 2014.

Forsyth, T.: Climate justice is not just ice, Geoforum, 54, 230–232, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.12.008, 2014.

Gerten, D. and Bergmann, S. (Eds.): Religion in Environmental and Climate Change: Suffering, Values, Lifestyles, Continuum International Publishing Group, London, UK, New York, NY, USA, 2011.

Gottlieb, R. S. (Ed.): The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Ecology, Oxford University Press, Oxford, USA, 2010.

Granovsky-Larsen, S.: Dealing with Peace. The Guatemalan Campesino Movement and Post-Conflict Neoliberal State, University of Toronto Press, Toronto Buffalo, London, Canada, 2019.

Grosfoguel, R.: La descolonización del conocimiento: diálogo crítico entre la visión descolonial de Frantz Fanon y la sociología descolonial de Boaventura de Sousa Santos, Formas-Otras: Saber, nombrar, narrar, hacer, CIDOB, Barcelona, Spain, 97–108, 2011.

Hafner, R.: Environmental Justice and Soy Agribusiness, in: Earthscan food and agriculture, 1st ed., Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, London, New York, NY, INBN 978-0-8153-8535-6, 2018.

Haluza-DeLay, R.: Religion and Climate Change: Varieties in Viewpoints and Practices, WIRES Clim. Change, 5, 261–279, https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.268, 2014.

Harris, P. G. (Ed.): A research agenda for climate justice, Edward Elgar Publishing, Northampton, UK, 2019.

Hernández Castillo, R. A.: Sur profundo: identidades indígenas en la frontera Chiapas-Guatemala, Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropologia Social, México, 2012.

Honty, G.: Cambio Climático: negociaciones y consecuencias para América Latina, Coscoroba/CLAES, Uruguay, 2011.

Jenkins, W.: Feasts of the Anthropocene: Beyond Climate Change as Special Object in the Study of Religion, South Atlantic Quarterly, 116, 69–81, https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-3749326, 2017.

Kerber, G.: Climate change and Southern theologies. A Latin American insight. (As alterações climáticas e as teologias do sul. Uma visão da América Latina, HORIZONTE) – Revista de Estudos de Teologia e Ciências da Religião, 45–55, https://doi.org/10.5752/P.2175-5841.2010v8n17p45, 2010.

Kirmani, N.: The Relationships between Social Movements and Religion in Processes of Social Change: A Preliminary Literature Review, Religions and Development Research Program, International Development Department, University of Birmingham, Department for International Development (DFID), UK, 2008.

Leff, E.: La apuesta por la vida: imaginación sociológica e imaginarios sociales en los territorios ambientales del sur, Siglo XXI Editores, México DF, Mexico, 2014.

Lorentzen, L. A. and Salvador, L.-A.: Religion and Environmental Struggles in Latin America, in: The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Ecology, edited by: Gottlieb, R. S., 510–534, Oxford University Press, Oxford, USA, 2006.

Mbembe, A.: Necropolitics, Public Culture, 15, 11–40, 2003.

Mignolo, W. D. and Escobar, A. (Eds.): Globalization and the Decolonial Option, 1st ed., Routledge, New York, NY, USA, Canada, 2013.

Narchi, N. E.: Environmental Violence in Mexico: A Conceptual Introduction, Lat. Am. Perspect., 42, 5–18, https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X15579909, 2015.

Navarro, M. L.: Subjetividades políticas contra el despojo capitalista de bienes naturales en México, Acta Sociol., 62, 135–153, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0186-6028(13)71002-8, 2013.

Orgaz, C. J.: ¿Qué es el Corredor Seco y por qué está ligado a la pobreza extrema en casi toda Centroamérica?, available at: https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-48186820 (last access: 16 May 2019), 15 May 2019.

Paz-Salinas, M. F.: Luchas en defensa del territorio. Reflexiones desde los conflictos socio-ambientales en México, Acta Sociol., 73, 197–219, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acso.2017.08.007, 2017.

Pellow, D. N.: What is Critical Environmental Justice?, 1st ed., Polity, Cambridge, UK, Medford, MA, USA, 2017.

Riessman, C. K.: Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences, SAGE Publications Ltd, London, UK, 2008.

Rivera, N.: Comunicado a la comunidad nacional e internacional. Asamblea de Pueblos Te Txe Chman, San Marcos, Prensa Comunitaria Km. 169, available at: https://comunitariapress.wordpress.com/tag/mam/ (last access: 29 April 2019), 2016.

Schlosberg, D.: Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature, 1st ed., Oxford University Press, USA, Oxford, 2009.

Sosa, M. and Camey-Huz, L.: Guatemal: del despojo a la gestación de alternativas, Revista Geonordeste, XXVI, 328–343, 2015.

Svampa, M.: Fronteras del neoextractivismo en América Latina Conflictos socioambientales, giro ecoterritorial y nuevas dependencias, Maria Sybilla Merian Center. Ed. Universitaria y UCR, FLACSO Ecuador, Germany, 2019.

Tamboukou, M.: A Foucauldian approach to narratives, in: Doing Narrative Research, edited by: Andrews, M., Squire, C., and Tamboukou, M., 102–120, SAGE Publications, London, UK, Thousand Oaks, California, 2013.

Toledo Pineda, M. A. C. and Coraza de los Santos, E.: Los mam de México y Guatemala: un pueblo binacional entre la autonomía y la heteronomía, Revista Pueblos Y Fronteras Digital, 14, 1–32, https://doi.org/10.22201/cimsur.18704115e.2019.v14.369, 2019.

Veldman, R. G., Szasz, A., and Haluza-DeLay, R.: How the World's Religions are Responding to Climate Change: Social Scientific Investigations, Routledge, New York, NY, USA, Canada, 2013.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Social movements as socio-environmental struggles in Latin American contexts: the eco-territorial turn

- Theoretical and methodological remarks

- Climate justice and the religion factor in socio-environmental struggles

- Discussion and conclusions

- Data availability

- Competing interests

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Social movements as socio-environmental struggles in Latin American contexts: the eco-territorial turn

- Theoretical and methodological remarks

- Climate justice and the religion factor in socio-environmental struggles

- Discussion and conclusions

- Data availability

- Competing interests

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement