the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

“It makes the buzz” – putting the demographic dividend under scrutiny

Elke Loichinger

Bernhard Köppen

We contribute to this theme issue on “(Re)Thinking population geography” with a critical engagement with the concept of the demographic dividend (DD). We put the DD – a concept based on interactions between demography, development and policy making – under scrutiny and investigate in particular whether a demographization of politics, a criticism concerning political decision-making based on a reductionist use of demographic data, as described by Barlösius (2007) and Schultz (2019), is happening.

Our findings, based on literature analysis and interviews with experts working in the field of development cooperation, policy advocacy and demographic research, show that simplistic demographic explanations for economic growth are appealing to political leaders and advocacy groups. In the context of the DD, demographization is being strategically used by advisors and scientists to convince and engage decision makers at all administrative levels in order to promote voluntary family planning, multi-sectoral development policies and human rights.

Our research suggests that the well-established and widely used paradigm of the DD might be a prominent example of what we call positive demographization. At the same time, particularly when it comes to the politicization of the female body through demographic intervention, the concept of the DD remains potentially prone to politically motivated interpretation and use.

- Article

(953 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

With regard to the improvement in human well-being and the quality of life, a prominent and seemingly undisputed link between population growth and development has regularly been established in public discourse when speaking about populations (Barlösius, 2007). Academic discussions concerning the negative impact of population (growth) on development have a long tradition, beginning in the 18th century (see also Etzemüller, 2007). However, perspectives have changed over time. Truly apocalyptic prophecies (e.g., by Thomas R. Malthus or Paul R. Ehrlich) stand vis-à-vis the idea of population growth as a precondition for innovation and prosperity (e.g., Johann P. Süßmilch and Julian L. Simon). As pessimistic scenarios became quite prominent in the 20th century, development policies focused on changing demographics of (further) growth (Connelly, 2008). This led in several instances to violations of human rights under the umbrella of development aid, most often directed against the female body, as women were reduced to their reproductive behavior in the context of economic growth scenarios (Raymond, 1994; Schultz, 2006; Harcourt, 2009).

Undoubtedly, population size, changes in age structure and spatial distribution are basic factors when discussing strategies in development cooperation or projecting the demographic as well as societal and economic future of countries in the Global South. In this context, the demographic dividend (DD), a paradigm for the relationship between population and development, is by now used globally. It was introduced by Harvard economist David Bloom and colleagues after empirical evidence concerning the impact of changes in populations' age structures on economic development was found for a group of Southeast Asian countries (the so-called Asian tiger states): South Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan serve as prototypical examples where a decline in fertility increased the share of people of working age (or, as the reverse conclusion, decreased the share of dependent and “unproductive” persons). This change in age distribution, in combination with investments in health and education as well as the emergence of employment opportunities and supportive macroeconomic institutions, is considered to have been the prerequisite for the observed increase in economic growth. Omitted here is the fact that besides policies of voluntary family planning and incentives, these economies put pressure on their populations in order to reach their goal of fertility decline (e.g., Baik and Chung, 1996, for South Korea) and serve as prototypes for “benevolent dictatorships” too (Fukuyama, 2012).

The DD concept is based on the reductionist but widely shared model of the demographic transition (DT) which describes changes from high to low fertility and mortality levels in several stages (see also Sect. 2). At first glance, the idea of a DD is easy to understand and quite convincing. The concept also seems to fit very well for development policy. However, planning and harvesting a DD based on target-oriented (political) actions are by far less trivial than they might seem. Furthermore, the potentially relevant factors for a DD are more complex and less susceptible than the core concept might suggest. In spite of that, the prospect of a potential DD raises hopes for economic growth and development among policymakers and organizations in the field of development cooperation, especially when it comes to sub-Saharan African countries with currently still comparatively high levels of fertility. For example, the formal German development cooperation has identified population dynamics as a pivotal cross-sectoral topic (Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2013). A growing number of nation states are developing “road maps” to harness the DD (United Nations Population Fund, 2019) and “Harnessing the Demographic Dividend through Investments in Youth” was the leitmotif of the African Union in 2017 (The African Union Commission, 2017). Economists, demographers, development planners and political decision makers are trying to replicate the path of successful Asian countries and to adapt the concept of the DD in Africa (e.g., Groth and May, 2017). Key scientific as well as non-scientific publications on the DD put emphasis on the importance of multi-sectoral perspectives when transferring the concept into development policy and tangible actions. Equality of gender and building and fostering high-quality education systems as well as efficient and accessible public health services in nations of the Global South are considered to be basic requirements within the DD framework (McNicoll, 2006; Crespo Cuaresma et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2016; Lutz et al., 2019).

From a critical perspective, however, some arguments related to the DD could also be the rationale of a neo-Malthusian agenda, including family-planning policies and the promotion of hormonal contraceptives. This is problematic in so far as past politics that focused on population control involved cases of blatant violations of human rights, from forced abortions to coerced sterilization of females and further interferences in individual decisions of family planning. Hence, the interactions between demography, politics and development related to the DD deserve critical investigation. This article puts the concept of the DD under scrutiny and investigates in particular whether a demographization of politics as described by Barlösius (2007) and Schultz (2019) is happening in the context of the DD and, if so, how. A presumable demographization of politics bears the risk of being contrary to individual sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), which is why we also suspect potential twisting of demographization in policy advocacy to generate positive, multi-sectoral outcomes by highlighting the potential of economic growth through a DD.

The findings of this paper are based on literature analysis and the analysis of qualitative interviews. We conducted 11 semi-structured interviews with 13 experts (1 interview took place with a team of 3 experts) from 10 organizations to get an insight into how the DD framework is perceived in the demographic research and development community. To preserve our interviewees' anonymity, we decided to classify our interviews via alias groups by the following criteria:

-

Interviewees 1.1 to 1.5 belong to the group “development cooperation”, which includes experts working for national or transnational agencies using the DD as a given concept in international development.

-

Interviewees 2.1 to 2.4 belong to the group “policy advocacy and private research institutes”, which contains experts in policy advocacy and private research institutions using the concept of the DD to promote their agendas.

-

Interviewees 3.1 to 3.4 belong to the group “independent academic research”, which involves independent academics working on demographic issues in development.

The interviews took place in person or (due to the COVID-19 pandemic) via Skype from November 2019 to June 2020. All but one interview, where no consent was given, have been recorded. Interviews held in German have been translated into English. The information has been transcribed, anonymized, coded and analyzed with MAXQDA following Keller's approach to discourse analysis from the sociology of knowledge (Keller, 2006, 2011).

We present the concept of the DD in Sect. 2, followed by a brief overview of the history of linking population and development and an introduction of the phenomenon of demographization. Section 4 provides a critical analysis of whether the DD has moved beyond past ideas of population control and family planning, while Sect. 5 examines under what conditions the DD might present a positive example of demographization. The final section summarizes and concludes our paper.

According to the United Nations Population Fund, the DD “refers to the temporary economic benefit that a country can earn from a significant increase in the ratio of working-age adults relative to young dependents that is created by rapid decline in birth rates” (United Nations Population Fund, 2017). We discovered some modifications and extensions to this definition which we will present further on in this section. In a first step, we present the concept of the DD as it was originally introduced and further developed by academics.

The concept of the DD relies on the widely shared concept of the demographic transition (DT), which entails significant changes in a population's age composition. The DT sets out with a decline in mortality, and there is usually a time lag before couples adjust their fertility downwards; the transition thus includes a phase of population growth during which the share of infants and children in the population rises. In the subsequent intermediate phase of the transition, fertility and population growth start to decrease. The share of the working-age population grows, and rates of child dependency decline, with the number of older persons remaining relatively small. According to Bloom et al. (2003), these changes in age structure open a so-called window of opportunity for a demographic dividend where a high share of the working-age population can generate revenue and economic benefits for the society. To make the most of this change in age composition, favorable social and economic policies as well as further investments in education and health are called for. The described change in age structure translates into an increase in savings per capita and is described by Bloom et al. (2017) as an accounting effect. This accounting effect is accompanied by a behavioral effect (Bloom et al., 2017), entailing an increase in female labor participation and higher investments in education per child. Over time, other researchers introduced a step-wise assessment of the DD. It included the definition of a first and a second dividend, largely depending on a country's phase of the DT and its ability to invest in its population's human capital (Mason et al., 2016). While the first dividend is perceived as transitory and largely linked to changes in age structure, the second demographic dividend depends on investments targeting a countries' human capital. The latest research puts emphasis on findings strongly suggesting that DD-related economic growth is imperatively linked to a combination of changes in the age structure and educational attainment (Lutz et al., 2019).

In the case of the Asian tiger states, a bonus of up to 40 % of the total economic growth resulted just from the shift in the region's age distribution, according to Bloom and Williamson (1998). These striking numbers raised a lot of attention in the community of international development cooperation and development planning, and the DD became one of the core concepts being used with regard to population dynamics; as one of our interviewees puts it,

I would say it's a recurrent element in our support to international policy dialogue. We have certainly addressed the topic in different international fora and events such as the European Development Days, the African Population Conference, the Nairobi Summit, etc. … I mentioned this earlier; this is certainly one of the core approaches that we have to population dynamics, to strengthen demography-sensitive policy planning. (Interviewee 1.3)

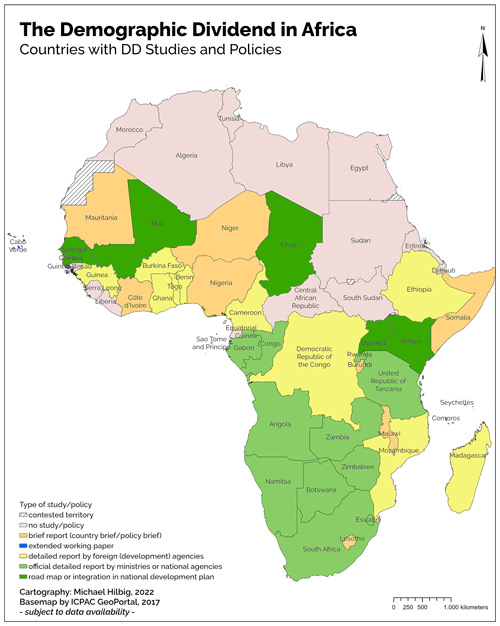

The DD has become a very prominent concept in international development planning, describing the relation of population dynamics and development and thereby promising economic growth effects through changes in age structure. Especially in sub-Saharan Africa, where the majority of countries are still in the early stages of their presupposed demographic transition, hopes for a DD are raised among politicians and policy planners. Detailed reports and studies regarding their potential of reaping a DD have been produced for most countries in the region, as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1Demographic dividend studies and policies in Africa (cartography: Michael Hilbig, 2022; basemap: ICPAC GeoPortal, 2017).

Six countries (Chad, Kenya, Mali, Senegal, Uganda and The Gambia) have implemented road maps to harness the DD or have adopted such policies in their national development plans.

For 11 countries, official governmental reports by ministries or national agencies can be found, and for another 11 countries, detailed studies have been published by foreign development agencies (for example, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Agence Française de Développement (AFD), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ)).

Country briefs and policy briefs have been published for eight countries and one extended working paper by the IMF in the case of Cabo Verde. The fertility transition in Mauritius has already been completed (total fertility rate – TFR – of 1.39) (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2019), making a dedicated DD policy obsolete. In conclusion, we were not able to find DD-related policies or studies for Guinea-Bissau, Sierra Leone, Liberia, the Central African Republic, South Sudan, Eritrea, Djibouti and Equatorial Guinea, which means that in only 8 out of 46 countries in sub-Saharan Africa no study or policy brief by national or international development agencies has been published. Considering the DD became important for development cooperation and policy advocacy, as well as for scholarly debates, even if skepticism among academics regarding the concept does exist:

It's fashionable to have a research project, to have a conference on the demographic dividend. I attended one in Paris a few years ago organized by the French development agency AFD. And I think, like the fact that GIZ does it, and I guess that they have it everywhere. And it is strange because, probably you have this experience also when you talk to researchers, no one believes really in it. But it makes the buzz. It is something you have to use it somehow, I guess. (Interviewee 3.1)

Contradictory to the high prominence of the DD in development planning, we discovered differing understandings concerning the definition of the DD. One interviewee even criticized the ambiguity of the DD as becoming a “vague term … being used in the community” (Interviewee 2.1). This practice of using the same term differently makes it sometimes difficult to create a comprehensive and consistent synopsis when comparing experts' statements. Two main strings of understanding materialized: the first is a reductionist, technical perception of the DD and refers to “automatic” changes in a population's age structure following a fertility decline over time, leading to a higher share of the working-age population and to economic growth effects if people are skilled and employed (e.g., Interviewee 1.1 or Interviewee 3.2). The second string of understanding refers explicitly to the DD as a process that needs multiple efforts to develop successfully. Demographic change does not imperatively produce economic growth, but it offers an opportunity to create an economic bonus amplified by demographic change if sustainable socio-economic development policies are already in place (e.g., Interviewee 1.3, Interviewee 2.1, Interviewee 3.1). An important detail of the underlying concept of the DD is its time criticalness. In this context, key literature and also some of our interviewees use the term of a “window of opportunity” (e.g., Interviewee 1.3), which is “a period of time which is particularly favorable to economic growth” (Interviewee 3.2). This time criticalness suggests urgency for politicians and decision makers to act quickly. Policy briefs such as “Sahel's countries window of opportunity – 38 years to harness Demographic Dividend” (Dramani et al., 2019) contain normative recommendations concerning population dynamics and intensify this pressure. One of the authors of the cited policy brief confirmed in a personal encounter that the urgency of 38 years has been deliberately constructed by limiting the investigation period to the year 2050. This is just one example, but it is evidence of the highly problematic use of demographization in policy consultation.

The first technical understanding of the DD bears the risk of oversimplification when it comes to DD-targeted policies, as it pays attention foremost to the transition of reproductive behavior and a fast decline in fertility. Linking generative behavior to economic prosperity is a pivotal characteristic of biopolitics (e.g., Foucault, 1990), where formal power is used to take over life decisions of the governed subject. With regard to the DD, the so-called East Asian Miracle developed hand in hand with family-planning policies, not all of which were voluntarily (Baik and Chung, 1996). What is new to the context of biopolitics and biopower is the role of private capital and philanthropic foundations defining novel, quantifiable targets in family planning (see exemplarily Brown et al., 2014, who argue for new targets, or Bendix et al., 2019, who critically engage with this development) beyond formally established political legitimation or accountability to those being subject to their biopolitical actions (Harman, 2016). The impact of family-planning discourses on the microsphere and body politics in international development deserves critical review, as individual life course decisions on sexuality and reproductive behavior might have become a determinant for economic prosperity again. In this regard, sexual and reproductive health and rights are no longer viewed as a universal right which needs to be guaranteed for its own sake but as a means to speed up a fertility decline to create economic growth. From this perspective, women are reduced to their wombs (Raymond, 1994). These critiques highlight important issues, and we recommend further reading from feminist perspectives, such as the work of Raymond (1994), Harcourt (2009) or Schurr (2017, 2018). A more elaborate presentation here would go beyond the scope of our analysis.

The basic idea of linking population and development appeared long before the concept of the DD was coined. Thomas R. Malthus' An Essay on the Principle of Population, as it affects the Future Improvement of Society (Malthus, 1798 [1985]), one of the earliest systematic demographic studies, introduced a prominent school of thought on interpreting population processes and society. Malthus argued that accelerated population growth would outpace agricultural production and, as a consequence, famine and starvation would be inevitable. The central argument of Malthus on sustainability versus population growth has been subject to debate since then and has had an important impact on political decisions concerning population control in the context of development policies in the 20th century. Discursive weapons, such as the “population bomb” (Ehrlich, 1971), eventually resulted in rigid, normative and radical national policies concerning fertility reduction in several countries with high population growth. French philosopher Michel Foucault named this new enforcement of power through the regulation of a population's reproductive behavior “biopolitics” (Foucault, 1990). Measures included forced sterilizations, often targeting women of marginalized ethnic groups or from lower-income groups (Solinger and Nakachi, 2016). Prominent examples were mass-sterilization camps in India (Ahluwalia and Parmar, 2016) or China's one-child policy (White, 2016).

A pivotal shift took place in 1994 with the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) held in Cairo. A new rationale concerning population and development was put in place: sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR). Normative programs on birth control and coercive measures were banned and emphasis was put on voluntary family-planning programs that respect individual and human rights (McIntosh and Finkle, 1995; Eager, 2004). The Cairo Programme of Action also had an impact on the work of those policy advocacy and private research institutions in the field which had been advocates of population control before. Interviewee 2.3 admits that his/her institution had to transform:

There were some advocacies, right, to reduce that kind of, reduce the rapid population growth, I think, to a large extent. Our institution [anonymized] played an important role there. Of course, you know after 1994, there's some transitions that are happening in our institution as well as like, you know, in the rest of the world … And we respect the human rights and also the rights of contraceptive health … and try to help the people in the developing countries to actualize their reproductive health and rights. (Interviewee 2.3)

The sheer size of countries' populations and quantifiable growth rates lost their significance for international development policy in favor of SRHR; other parameters like the unmet need for contraception (the number of girls and women that are willing to use but do not have sufficient access to contraceptives) or the contraceptive prevalence rate gained in importance. While the described program of action meant turning away from population control, more or less obvious (partially institutionalized) violations of this principle remain in national population politics or stakeholder paradigms (Bhatia et al., 2019). According to Hardt and Negri (2000) recent biopolitical production is financed and performed by supranational institutions, private foundations or non-governmental organizations which have no democratic legitimization. In this context, the prominent role of philanthropic foundations such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation or The Rockefeller Foundation or private research institutions like the Population Council merit critical attention as these institutions provide a high share of financial support to the international global health agenda and especially to family-planning programs.

Strictly speaking, Malthus' essay, together with Süßmilch's preceding (however quite differing) considerations, are very early examples of demographization. Demographization describes the phenomenon when demographic statistics and measures are being used to justify certain policies in areas that are presumably affected by these demographic developments: “Demographization refers to an epistemology within which social conflicts and problems are interpreted as demographic conflicts or problems and within which demographic or population policies are highlighted as solutions” (Schultz, 2019:645). This implies that other avenues of explanation are not explored and, consequently, the suggested potential measures for targeting economic or societal challenges are also very limited to directly addressing the presumed purely demographic problem. Often, these narratives are accompanied by highlighting the presupposed “objectivity” of statistics and mathematics. An example of such a narrative in the spirit of demographization is the call for the selected migration of persons with skills that are in high demand but in short supply in countries with a decreasing number of persons of working age (cf. Messerschmidt, 2017). Could it not also be that companies might not have invested adequately in trainees and that boosting such investment might be at least part of the solution as well? Another related example is the production of population projections and their use for narratives around immigration policies (cf. Schultz, 2019).

Barlösius (2007) and Schultz (2019) argue that the demographization of politics should be recognized as a problematic issue in contemporary political decision-making due to its reductionist use of demographic data which restricts the range of potential strategies and excludes other important aspects, such as (social) inequality. This also concerns the use of “population” instead of “society”, which in itself has an effect on the way the discourse around present and future demographic developments is framed. To what extent the DD qualifies as an example of demographization will be explored in Sect. 5.

After the Cairo consensus and its new emphasis on SRHR, the population control movement seemed to have lost its main argument for birth control in the development discourse. Generally, a normative change to sexual and reproductive health and rights did happen (Eager, 2004). Nonetheless, not all national population politics necessarily respected the agreed-upon principles, e.g., in Alberto Fujimori's Peru (Schultz, 2006; Battaglia and Pallarés, 2020) or China's well-documented one-child policy.

Population control as a paradigm was resurrected again in a new wrapping when David Bloom and Jeffrey Williamson published their work on the demographic transition of East Asian countries and its impact on the so-called East Asian economic miracle (Bloom and Williamson, 1998). The ground for the DD was laid, and their findings fueled the argumentation of those who called for population control, especially in the Global South. According to Interviewee 3.3, these findings provided a new basis for the community of the former birth control movement as the DD depends on rapid fertility decline to achieve changes in age distribution and higher shares of the working-age population:

It's just a different flavor. And at the same time, for Africa in particular, it wasn't saying `Oh my God, the situation is terrible, you have these extremely rapid population growth rates above blah [sic]'. The way many people choose to hear these ideas anyway in Africa is that `Ah, someone is now saying our youth is a tremendous resource and will lead to rapid growth' or something like that. (Interviewee 3.3)

The world's future development seems to depend on a fertility decline in the Global South again. But with the DD, it is attached to the prospect of economic growth and prosperity instead of fears of overpopulation, starvation and hunger crises.

I think part of the appeal of the demographic dividend has been that it seemed to sidestep these issues around population growth rate and population size and density. I say `seems to' because in fact the population age distribution is closely linked to the population growth rate. (Interviewee 3.3)

While the interviewees from our group of independent academic research seem more aware of the implications of the DD paradigm in the context of individual reproductive rights and more hesitant about the economic outcomes (Interviewee 3.1 in Sect. 2), we discovered different approaches within the representatives of policy advocacy and private research institutes, even if they seem aware of this sensitive issue:

For demographic development, in the way we postulate it with the demographic dividend, we need child numbers to go down. But the important thing is that we cannot reach this with measures. In a human-rights-based approach, of course, it cannot be reached by measures like China for example implemented it. (Interviewee 2.4)

As an example of the new biopolitical regimes, a new alliance of organizations, the FP2020 initiative, was forged at the London Summit on Family Planning in 2012, advocating for a wider spread of modern hormonal contraception: an additional number of 120 million girls and women should become users of modern contraception by the end of the year 2020 (Brown et al., 2014). According to the last progress report, the initiative missed its goal. Still, 60 million girls and women had been reached by the end of the year 2020 (FP2020, 2021b). Furthermore, the initiative announced it would extend its work to the year 2030 (FP2020, 2021a). While the initiative emphasizes its attempt as honoring SRHR as part of human rights, it can also be seen as a new uprising of explicit population policy by setting new targets and has therefore faced some critique (Bendix et al., 2019). This criticism especially focuses on the major role of hormonal implants and self-injectables in the “120 by 20” campaign. These were intended to help women in rural areas to become independent from the local and often weak public health systems. But especially if local public health systems are weak, non-removable implants might not be the best solution if women experience unintended side effects. Poor possibilities of follow-up care (Interviewee 3.4) and a high emphasis on hormonal contraception do not guarantee a woman's right to make an elucidated decision to choose the best contraceptive for her individual situation.

Nonetheless, it is undisputable that population growth is affecting development and resource consumption and can have severe environmental impacts. It is a very complex balancing act for development planning and policy advocacy between the intention of lowering fertility for better chances to develop in the future by on the one hand exerting influence through purposive education and on the other hand respecting individual life course decisions of families and especially women. All of our interviewees pointed out that fertility decline (e.g., to the replacement level) might be helpful for global sustainable development. For example, Interviewee 1.1 stresses the ecological side effects of population growth on the planet , especially if resource consumption levels per capita globally move towards recent high levels of consumption in the Global North:

But it's certainly true that a world population of 15 billion at the end of the century versus a world population of 7 billion, the difference between those two figures, right, double, has got to have strong environmental impacts. Again, though, we never go and say we need to get in there and control population. But it does mean that `Oh, hey, there's an important side benefit' to making sure everyone's rights are met. For family planning, for example, it's going to bring us down to the reasonable targets that were, you know, climate targets that we're aiming at. (Interviewee 1.1)

As it turns out, policy can act to avoid undesired high fertility without conflicting with SRHR – by making a wide range of contraceptives and information on contraceptive use available through education:

I am very sure if you educate all women and have a 100 % education, which is a basic human right, I believe that the fertility level would change. And that change is not necessarily to mean that I am controlling the population. Rather I am giving them the tool to decide on what do they want for their families. So I see the provision of family planning through programs such as contraceptive programs, information, as just one of the components to allow women to decide. (Interviewee 2.1)

It is widely believed that fertility will decrease if people in the Global South have better access to education and if sufficient access to a variety of contraceptives is available. Key literature on the DD even proposes calling the DD an “education dividend” (Crespo Cuaresma et al., 2014; Lutz et al., 2019) as investments in education affect not only reproductive behavior but also aspects like gender equality and the average qualification level of a population.

Based on this assumption, there would also be no need for propaganda or radical interventions promoting smaller families. Instead, investments in education will do the job anyway and not only shape populations' structure but also raise potential for economic development at the same time. Ending this section with this in mind raises a final question: what is the special value of the DD for development planning and policy advocacy? Or, as one interviewee criticizes,

Why do we need the DD? If the DD is depending on education policy, on social policy, then we could emphasize these fields for themselves. (Interviewee 3.4)

If the DD is meant to refer not exclusively to demographic aspects but to a larger set of policies, the question is why the demographic factor remains so salient. On the one hand, the analysis in the previous section already pointed towards the risk of having a too narrow focus on fertility as a pivotal precondition for development. Such a view is rather simplistic and needs to be reconsidered.

The dividend does not actually occur exclusively due to demographic change but must be accompanied by a whole suite of bigger and in my mind even more challenging investments in human capital and in the macroeconomic environment. (Interviewee 2.2)

On the other hand, easy-to-understand demographic factors as a prerequisite for economic growth seem to appeal to politicians (Interviewees 2.2, 2.4, 3.3, 3.4). Therefore, advocates and consultants target those politicians who do not “fully understand the concept of the demographic dividend” (Interviewee 2.4) with simplistic demographic explanations and the promise of economic growth due to demographic changes.

And exactly this appeal, the demographization of development planning, has been recognized for development cooperation and policy advocacy. The concept of the DD may serve as a door opener for a broader policy dialogue on development factors other than population. The true complexity and preconditions for a successful DD can be introduced to decision makers step by step. A related aspect is that policy advisors and consultants often seem to face the problem of uninformed and/or uninterested decision makers (Interviewees 1.1, 1.3, 2.2, 2.3, 2.4 and 3.1). The following example refers to a basic video, explaining the core principles of the DD, which was produced by the interviewee's institution:

The audience is a very busy government policy maker. Who's not a demographer? Who may or may not be an economist? … Who's going to quickly stop watching your video and start doing something on their phone if the story is hard to follow or pessimistic or confusing? (Interviewee 2.2)

Therefore, the DD and especially its suitability to demographize a variety of aspects related to human rights and sustainable development goals (SDGs) can also be viewed as a vehicle for policy advisors and those working in development cooperation to enhance and strengthen multi- and cross-sectoral policies. We identify this as a twist to the existing critique of demographization. Being asked if the DD works as a medium or vehicle to attract high-level politicians to invest more into a wider set of development policies by showing the impacts with demographic data, Interviewee 2.4 confirms as follows:

Yes, that's what we are hoping for. And that is why we are working on it all the time. Because again, our world is very much working on economic rationalities, you know, like if you tell people, `Well if you do this, you will see economic growth.' It's always appealing; it's always something people want to reach for in our society. You can criticize that, but that's another topic. So I would say that again the concept of the demographic dividend is something really appealing to countries of the Global South. And for us it is a concept highlighting those areas of needed intervention. (Interviewee 2.4)

In this function the justified criticism of oversimplification of the impacts of population dynamics on development helps to strengthen broader development policies. On the one hand, simplicity is needed because decision makers in politics might not fully understand the principles behind the DD. On the other hand, simplicity is perceived to be needed to raise attraction in political spheres when lobbying for development policies. Thus, the DD as a strikingly handy concept also became a tool to advocate for e.g., education, public health or gender equality:

It [the prospect of the DD] helps to think about how these sectors intersect and how they can work together with demographic change. So, I do think that it's a very helpful paradigm to start thinking about demographic change cross-sectorally and to bring the very different stakeholders and actors together. (Interviewee 1.3)

This is also why experts refer to a broad set of studies assessing the importance of policies in different fields of development:

I see the research taking a look at all these different parts of the demographic dividend as really important, but I think only the whole picture can actually bring a good result. (Interviewee 2.4)

Or, as Interviewee 3.3 adds,

One of the things that makes me feel okay about the Africa seizing this demographic dividend idea as a key to development, one of the reasons I feel okay with that is that it leads to policy ideas like, `Yes, you have to invest in education and do good things for youth employment and health and so on'. I think those are all great policies, and I think they do flow from the dividend idea. (Interviewee 3.3)

Strengthening the engagement in gender equality, education or family planning in terms of providing access to contraceptives and guaranteeing SRHR with the prospect of a DD not only is favorable in this specific context but also relates to basic human rights, with or without the DD.

Well, I think the kinds of policies that are suggested by an emphasis on the demographic dividend are also good in general. And that would mean I do support voluntary family-planning programs in the sense of improving access to contraceptives. And I certainly support policies to increase educational enrollments, investment in education, and I support policies to develop labor opportunities for young workers. (Interviewee 3.3)

Yet designing development policy while openly calling for a rapid fertility decline at the same time can pose a threat to the paradigm of SRHR. While feminist academics often criticize the framework of SRHR in population policies as a reduction of “women as reproductive bodies” (Raymond, 1994; Harcourt, 2009), the DD framework gives women the opportunity to be seen as socially and economically acting individuals in need of decent and comprehensive health care, high-quality education, and job opportunities. Indeed, these achievements often need to be reduced to their impact on fertility and economic growth in the first place to be implemented instead of being understood as basic human rights. But if the DD leads to a holistic understanding of development guaranteeing basic human rights in the sphere of political decision-making, it would lead to a positive outcome. Under these conditions, we come to the conclusion that the DD can be seen as an example of what we call positive demographization.

The demographic dividend (DD) is currently one of the most important concepts within development cooperation and is used by governmental and non-governmental organizations alike. The concept draws new attention to the interplay of population and development. It is a leading paradigm for development cooperation, especially in Africa, where many countries are still in the early stages of their demographic transition. Hence, it was high time that the concept of the DD was put under scrutiny, particularly its use of demographic arguments for development purposes.

While our literature analysis and analysis of qualitative interviews showed slightly differing understandings of the DD among the scholarly community and international development advisory and practice, it is still possible to draw several general conclusions. Our findings reveal that simplistic demographic explanations for economic growth are appealing to political leaders and decision makers, which probably explains to a large extent the popularity that the DD has gained in the development context. We also find that while the framing of the role of population for (economic) development is a different one compared to the framing before the ICPD in 1994 in Cairo – the focus now is on a change in populations' age structure, the prerequisite for reaping the benefits of a DD is still a reduction in fertility. However, it is understood that this reduction has to be the result of voluntary changes in fertility behavior and any actions by states or organizations to that avail have to adhere to individual and human rights. This is a clear distinction from previous problematic approaches related to population control. Having said that, it must be clear from experiences in the past that it can be a thin line between what is considered voluntary and where undue influence from political and non-political actors starts. From a feminist perspective, the DD is, without a doubt, a highly problematic concept. The DD focuses on individual sexual and reproductive decisions in the microsphere as part of national development, especially in economic terms, and in the macrosphere, instead of on a universal human right.

At the same time, the paradigm of the DD offers the chance for SRHR, educational expansion, gender equality and social welfare to be prominently considered within development policy as these areas are crucial to reaping economic benefits from a changing demography. In addition, women's qualifications and their human capital and economic activity are increasingly recognized in national and international DD frameworks as crucial elements for economic development.

We further conclude that a demographization of politics as described by Barlösius (2007) and Schultz (2019) is to a certain extent happening. The DD represents a data-driven approach where developments of demographic and economic indicators from specific countries are treated as role models for development in other countries, bearing the risk of oversimplification. Nonetheless, the specific demographization tendencies identified in our research have unambiguous positive elements that other prominent examples of demographization are lacking. We hence argue that the described promotion of the DD to decision makers as a low-level vehicle in order to achieve support for broader sets of multi- and cross-sectoral policies could be perceived as an example of positive demographization. Investments in education and population health, the creation of decent and productive employment opportunities, and the advancement of gender equality are all examples of core policy areas of the concept of the DD that are deemed essential for improvement in overall living conditions and individual well-being (United Nations General Assembly, 2015). As such, the DD proves to be a powerful tool for policy advocacy within development cooperation in order to enhance multi-sectoral policies such as educational policy, public health and family-planning policies in a broader context of promoting human rights and SDGs. Therefore, policies to harness the DD, if implemented correctly, strengthen gender equality and SRHR as individual rights, even if politicians do not intend to strengthen them for their sake. Nevertheless, the concept of the DD remains potentially prone to politically motivated interpretation and use that is to some extent in line with the critical perception of demographization, and close monitoring of future use of the DD in the context of population and development is warranted. In instances where the prospects of a DD are the rationale for forcibly limiting (via either direct or indirect measures) the population size or changing demographic structures, the DD would lose the positive notion we identified.

Finally, economic and social development depends on numerous factors and not all of them can be influenced by policies on the national level as development is always embedded in a broader global context. Trade policies, financial regulations and demographic developments in other parts of the world, to name just a few areas, have global implications. This aspect that limits countries' possibilities of shaping their economic fate by themselves should receive more attention in future employment of the DD concept.

The data (qualitative data, based on personal interviews) are not publicly available but can be requested in anonymized form from the corresponding author.

MH and BK developed the concept of the paper. MH conducted and analyzed the interviews. MH, EL and BK wrote the initial paper. MH and EL revised the paper.

The contact author has declared that neither they nor their co-authors have any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors would like to thank our anonymous interviewees that agreed to take part in our study. We also would like to express our gratitude to the editor and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive remarks and annotations.

This paper was edited by Nadine Marquardt and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Ahluwalia, S. and Parmar, D.: From Gandhi to Gandhi: Contraceptive Technologies and Sexual Politics in Postcolonial India, 1947–1977, in: Reproductive states: Global perspectives on the invention and implementation of population policy, edited by: Solinger, R. and Nakachi, M., Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York, 124–155, ISBN 9780140432060, 2016.

Baik, Y. and Chung, J. Y.: Family policy in Korea, Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 17, 93–112, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02265032, 1996.

Barlösius, E.: Die Demographisierung des Gesellschaftlichen: Zur Bedeutung der Repräsentationspraxis, in: Demographisierung des Gesellschaftlichen, edited by: Barlösius, E. and Schiek, D., VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden, 7–34, ISBN 9783531150949, 2007.

Battaglia, M. and Pallarés, N.: Family Planning and Child Health Care: Effect of the Peruvian Programa de Salud Reproductiva y Planificación Familiar 1996–2000, Popul. Dev. Rev., 46, 33–64, https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12312, 2020.

Bendix, D., Foley, E. E., Hendrixson, A., and Schultz, S.: Targets and technologies: Sayana Press and Jadelle in contemporary population policies, Gender Place Cult., 10, 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1555145, 2019.

Bhatia, R., Sasser, J. S., Ojeda, D., Hendrixson, A., Nadimpally, S., and Foley, E. E.: A feminist exploration of “populationism”: engaging contemporary forms of population control, Gender Place Cult., 44, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1553859, 2019.

Bloom, D. E. and Williamson, J. G.: Demographic Transitions and Economic Miracles in Emerging Asia, World Bank Economic Review, 12, 419–455, https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/12.3.419, 1998.

Bloom, D. E., Canning, D., and Sevilla, J.: The Demographic Dividend: A New Perspective on the Economic Consequences of Population Change, Population Matters, Santa Monica, xvii, 106, https://doi.org/10.7249/MR1274, 2003.

Bloom, D. E., Kuhn, M., and Prettner, K.: Africa's Prospects for enjoying a Demographic Dividend, J. Dem. Econ., 83, 63–76, https://doi.org/10.1017/dem.2016.19, 2017.

Brown, W., Druce, N., Bunting, J., Radloff, S., Koroma, D., Gupta, S., Siems, B., Kerrigan, M., Kress, D., and Darmstadt, G. L.: Developing the “120 by 20” goal for the Global FP2020 Initiative, Stud. Family Plann., 45, 73–84, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00377.x, 2014.

Connelly, M.: Fatal misconception: The struggle to control world population, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 521 pp., ISBN 9780674034600, 2008.

Crespo Cuaresma, J., Lutz, W., and Sanderson, W.: Is the demographic dividend an education dividend?, Demography, 51, 299–315, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0245-x, 2014.

Dramani, L., Akpo, E., Djigo, Diama Diop, Dia, and Kama, M. C. N.: Sahel's countries Window of Opportunity- 38 years to harness Demographic Dividend, Sahel Women Empowerment & Demographic Dividend, SWEDD Policy Brief, 7 pp., https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.28738.53442, 2019.

Eager, P. W.: From Population Control to Reproductive Rights: Understanding Normative Change in Global Population Policy (1965–1994), Glob. Soc., 18, 145–173, https://doi.org/10.1080/1360082042000207483, 2004.

Ehrlich, P.: Die Bevölkerungsbombe, Hanser, München, 191 pp., ISBN 3446114068, 1971.

Etzemüller, T.: Ein ewigwährender Untergang: Der apokalyptische Bevölkerungsdiskurs im 20. Jahrhundert, X-Texte zu Kultur und Gesellschaft, Transcript-Verl., Bielefeld, 215 pp., ISBN 3-89942-397-6, 2007.

Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development: Population dynamics in German development cooperation, Position Paper, BMZ Strategy Paper, 10/2013, 18 pp., 2013.

Foucault, M.: The history of sexuality, Reprint, Penguin Books, London, 168 pp., 1990.

FP2020: Building FP2030: A Collective Vision for Family Planning Post-2020, United Nations Foundation, https://www.familyplanning2020.org/Building2030, last access: 18 June 2021a.

FP2020: The Arc of Progress 2019–2020: Condensed Print Version, United Nations Foundation, http://progress.familyplanning2020.org/sites/default/files/FP2020_ProgressReport2020_WEB.pdf (last access: 18 March 2022), 2021b.

Fukuyama, F.: The Patterns of History, J. Democr., 23, 14–26, https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2012.0005, 2012.

Groth, H. and May, J. F. (Eds.): Africa's population: in search of a demographic dividend, Springer, Cham, 526 pp., ISBN 9783319468877, 2017.

Harcourt, W.: Body politics in development: Critical debates in gender and development, Distributed in the USA exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan, London, New York, New York, NY, 226 pp., ISBN 9781842779354, 2009.

Hardt, M. and Negri, A.: Empire, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 478 pp., ISBN 0-674-25121-0, 2000.

Harman, S.: The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Legitimacy in Global Health Governance, Glob. Gov., 22, 349–368, 2016.

ICPAC GeoPortal: Africa Shapefiles, available at: http://geoportal.icpac.net/layers/geonode:afr_g2014_2013_0 (last access: 18 March 2022), 2017.

Keller, R.: Analysing Discourse. An Approach From the Sociology of Knowledge, Histo. Soc. Res.,, 31, 223–242, https://doi.org/10.12759/HSR.31.2006.2.223-242, 2006.

Keller, R.: Diskursforschung: Eine Einführung für SozialwissenschaftlerInnen, 4. Auflage, Qualitative Sozialforschung, Band 14, VS Verlag, Wiesbaden, 1136 pp., https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-92085-6, 2011.

Lutz, W., Crespo Cuaresma, J., Kebede, E., Prskawetz, A., Sanderson, W. C., and Striessnig, E.: Education rather than age structure brings demographic dividend, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 116, 12798–12803, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1820362116, 2019.

Malthus, T.: An essay on the principle of population as it affects the future improvement of society, with remarks on the speculations of Mr. Godwin, M. Condorcet, and other writers, Penguin classics, Penguin Books, London, 291 pp., ISBN 9780140432060, 1798 [1985].

Mason, A., Lee, R., and Jiang, J. X.: Demographic Dividends, Human Capital, and Saving, Journal of the economics of ageing, 7, 106–122, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeoa.2016.02.004, 2016.

McIntosh, C. and Finkle, J.: The Cairo Conference on Population and Development: A New Paradigm?, Popul. Dev. Rev., 21, 223–260, 1995.

McNicoll, G.: Policy Lessons of the East Asian Demographic Transition, Popul. Dev. Rev., 32, 1–25, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2006.00103.x, 2006.

Messerschmidt, R.: Demografisierung des Gesellschaftlichen, in: Macht in Wissenschaft und Gesellschaft: Diskurs- und feldanalytische Perspektiven, edited by: Hamann, J., Maeße, J., Gengnagel, V., and Hirschfeld, A., Springer VS, Wiesbaden, 319–357, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-14900-0, 2017.

Miller, T., Saad, P., and Martínez, C.: Population Ageing, Demographic Dividend and Gender Dividend: Assessing the Long Term Impact of Gender Equality on Economic Growth and Development in Latin America, in: Demographic Dividends: Emerging Challenges and Policy Implications, edited by: Pace, R. and Ham-Chande, R., Springer International Publishing, Cham, 23–43, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32709-9_2, 2016.

Raymond, J.: Women as Wombs: Reproductive Technologies and the Battle over Women's Freedom, Spinifex Press, s.l., 495 pp., ISBN 9781875559411, 1994.

Schultz, S.: Hegemonie – Gouvernementalität – Biomacht: Reproduktive Risiken und die Transformation internationaler Bevölkerungspolitik, Westfälisches Dampfboot, Münster, 388 pp., ISBN 3-89691-636-X, 2006.

Schultz, S.: Demographic futurity: How statistical assumption politics shape immigration policy rationales in Germany, Environ. Plann. D, 37, 644–662, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818772580, 2019.

Schurr, C.: From biopolitics to bioeconomies: The ART of (re-)producing white futures in Mexico's surrogacy market, Environ. Plann. D, 35, 241–262, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775816638851, 2017.

Schurr, C.: The baby business booms: Economic geographies of assisted reproduction, Geography Compass, 12, e12395, https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12395, 2018.

Solinger, R. and Nakachi, M. (Eds.): Reproductive states: Global perspectives on the invention and implementation of population policy, Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York, 389 pp., ISBN 9780199311088, 2016.

The African Union Commission: AU roadmap on Harnessing the Demographic Dividend through Investments in Youth, 27 pp., https://wcaro.unfpa.org/en/publications/au-roadmap-harnessingthe-demographic-dividendthrough-investmentsin-youth (last access: 18 March 2022), 2017.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: Demographic Profiles: Sub-Saharan Africa, World Population Prospects, https://population.un.org/wpp/Graphs/1_Demographic Profiles/Sub-Saharan Africa.pdf (last access: 18 March 2022), 2019.

United Nations General Assembly: Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015 70/1, Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 35 pp., https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (last access: 18 March 2022), 2015.

United Nations Population Fund: Unlocking Rwanda's Potential to Reap the Demographic Dividend, 96 pp., https://www.afidep.org/download/unlocking-rwandas-potential-to-reap-the-demographic-dividend-2/ (last access: 18 March 2022), 2017.

United Nations Population Fund: Programming the Demographic Dividend: from Theory to Experience, 139 pp., https://wcaro.unfpa.org/en/publications/programming-demographic-dividend-theory-experience (last access: 18 March 2022), 2019.

White, T.: China's Population Policy in Historical Context, in: Reproductive states: Global perspectives on the invention and implementation of population policy, edited by: Solinger, R. and Nakachi, M., Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York, 329–368, ISBN 9780199311088, 2016.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- The concept of the demographic dividend – origin and development

- Population, development and the demographization of politics

- Old wine in new wineskins – the demographic dividend makes the buzz

- Positive demographization – the hidden potential of a reductionist approach for development

- Conclusion

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References

positive demographization.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- The concept of the demographic dividend – origin and development

- Population, development and the demographization of politics

- Old wine in new wineskins – the demographic dividend makes the buzz

- Positive demographization – the hidden potential of a reductionist approach for development

- Conclusion

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References