the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Forum: Russia, Europe and the colonial present: the power of everyday geopolitics

Stefan Bouzarovski

Christine Bichsel

Dominic Boyer

Slavomíra Ferenčuhová

Michael Gentile

Vlad Mykhnenko

Zeynep Oguz

Maria Tysiachniouk

- Article

(648 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(430 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

During the past few months, the residents of most Ukrainian cities have been subjected to extensive blackouts as a result of Russian air strikes on energy production, transmission and distribution facilities. Military objectives aside, such actions are often justified along the lines of “Russia is just taking back [the] infrastructure that they owned 40 years ago”1. This reflects a deeper and more pervasive discourse across the Russian polity: the notion that Ukraine owes its modernity, or for that matter its entire existence, to Russia. As pointed out by Vladimir Putin in his de facto declaration of war on 24 February 2022, “modern Ukraine was entirely created by Russia or, to be more precise, by Bolshevik, Communist Russia” (Putin, 2022). The wanton demolition of vital socio-technical installations that underpin the comforts of contemporary life, therefore, is not simply an effort to assure military advancement – it also symbolically expresses a payback of the civilizational debt that the disobedient victims of these acts owe to empires past and present.

In this intervention, I aim to explore how energy infrastructures across Eastern and Central Europe (ECE) and the EU embody both the “colonial past” and “colonial present” (Davis and Robbins 2018; Gregory 2004) in the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Derek Gregory's (2004:xv) well known definition of the colonial present focuses on the constellations of power, knowledge and geography that continue to colonize lives all over the world. Omar Jabary Salamanca (2016) powerfully illustrates this condition in relation to contemporary Palestine, for instance, by emphasizing the ways in which infrastructures matter both symbolically and physically as concrete expressions of settler colonialism and uneven development – they are “material objects involved in the social and political production and reconfigurations of colonial space and life” (Salamanca, 2016:76).

Inspired by this work, I seek to shed a critical light on the overlapping post-colonial and geopolitical realities that shape Eastern and Central Europe's contemporary energy geographies. I explore the contingencies that are at play in shaping ongoing state policies and responses to Russia's invasion of Ukraine. This includes the infrastructural legacies of post-socialism and subsequent transformations, as well as the region's positioning within Europe's imaginary and material geopolitical map. I interpret the region's inherited socio-technical systems through the lens of visions, priorities and interests imposed by Soviet and Russian power structures (Bouzarovski, 2009). I also interrogate how this apparatus is both articulated through and challenged by everyday energy demand and social reproduction practices.

In theoretical debates, one of the ramifications of the Russian invasion of Ukraine is the foregrounding of Russian colonialism as a distinctive political-economic and cultural regime, predicated upon the domination, oppression and exploitation of neighboring Eurasian nations in particular. Botakoz Kassymbekova and Erica Marat (2022) speak of the hegemonic imaginaries that underpin this form of supremacy. Arguing that it is time to question Russia's self-defined “imperial innocence”, they contend that at the heart of this country's sense of militant patriotism lies the idea that its “rule on non-Russian populations is not colonialism but a gift of greatness” (Botakoz-Kassymbekova and Marat, 2022:1). The “historical self-image of a civilizing power” (Botakoz-Kassymbekova and Marat, 2022:2) is coupled with a victim narrative to yield the image of an altruistic and benevolent force for citizens both within and beyond the Russian state throughout history. This portrayal has also been extended to the Soviet Union (Linde, 2016), whose interpretation as a colonial project remains somewhat marginalized and is often contested not only within Russia, but within many liberal and progressive circles across both the Global North and the Global South.

One of the less recognized aspects of the Soviet colonial legacy – and its contemporary incarnation through the actions of Russian governing elites – is the emergence of socio-technical systems for the generation and consumption of energy. Russia's imperial influence on the European energy system, in particular, is a terrain on which many struggles have been politically enacted, not only recently, but throughout the 3-decade-long existence of Russia as an independent state, as well as the Soviet Union that preceded it (Högselius, 2013; Kuzemko et al., 2022). Hydrocarbons such as oil and gas are at the core of these infrastructural relationships, as they are believed to embody the capacity to yield and project geopolitical power across large territorial domains. As Mark Bassin and I argued back in 2011, the “key underlying feature that defines the energy relations between Russia and most of its neighbouring states is the massive hydrocarbon endowment of the former as opposed to the clear dependency of the latter on energy imports” (Bouzarovski and Bassin, 2011:787). As a result, “Russia likes to see itself as an energeticheskaia sverkhderzhava, or energy superpower”, placed at the “very heart of a new global regime of energy security” where it “would act as the leading guarantor of international development and stability” (Bouzarovski and Bassin, 2011:788). A corollary to this is the Putinist vision for regional domination via energy exports, not merely as a commercial commodity but also explicitly as a geopoliticheskoe oruzhie or “geopolitical weapon”.

While energy superpower narratives are often attributed to a set of Putinist doctrines – arguably and in part thanks to the current Russian president's specialist knowledge of the energy industry, epitomized by his completion of a PhD on the subject in the 1990s – the underlying ideologies and practices of Russian domination across the Eurasian post-socialist space are firmly rooted in the Soviet era. The Soviet Union built an energy system predicated upon the networked geographies of what Corey Johnson (2017) calls “distant carbon”, involving a vast radial pipeline network extending out of the Russian resource heartland and discouraging direct connections among other countries in the region. Even the names of some of the pipelines – “Friendship”, “Brotherhood”, etc. – are illustrative here.

Resource addiction to Russian hydrocarbons was one of the main implications of this situation, with ECE being dependent on the Soviet Union for 31 % of its total primary energy supply (TPES) in 1989, “including extremes of 68 percent in Bulgaria and 48 percent in Hungary” (Bouzarovski, 2010:172). Even the fossil-resource-endowed economies of countries such as Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan remained dependent on the Soviet pipeline infrastructure – “based largely on Russian territory and under Russian control” (Bouzarovski and Bassin, 2011:789) – to export their products.

When academics and pundits talk about the legacies of post-socialism in Eastern and Central Europe, they attribute them to the ideological, material and procedural features of the centrally planned economy and one-party state. Understandings of the “obdurate infrastructures” inherited from the period of Soviet domination – to use another concept coined by Corey Johnson (2017) – have rarely been approached through a post-colonial lens (in the context of past or enduring imperial ambitions and articulations). Yet the socio-technical systems for the supply, transmission and consumption of energy built across the entire post-socialist space both emerged and were controlled from a single center, despite local modifications and variations. This extends beyond fossil energy to encompass, for instance, nuclear power, whose generation was restricted to three basic reactor types – the RMBK, the VVER 440 and the VVER 1000 – dependent on Soviet manufacture, expertise and maintenance (Bouzarovski, 2010). Even today, countries who rely on these designs – e.g., Bulgaria, Hungary and Slovakia – are having to import Russian nuclear fuel, which remains outside the EU's sanctions regime (Melchior, 2022).

However, the dominance of Russian political and technological power was not restricted to the supply side of the energy sector. Much has been written about the “mikroraion” – the basic organizational form of Soviet housing provision – yet we rarely talk about its underlying imperial undertones. The socio-technical blueprints that governed how energy was consumed in large post-socialist housing estates – I note here the hub-and-spoke, centralized district heating energy systems for the provision of domestic hot water and ambient warmth – had specific origins within Soviet (Browne et al., 2017), and more specifically Russian, “strategies of political stabilisation” (Šiupšinskas and Lankots, 2019:304). The organization of public transport systems followed specific planning patterns; some underground transport systems in ECE still use rolling stock manufactured in the Soviet Union – in that sense, the “colonial present” is very much alive. Urban centers linked to specific forms of energy extraction provide another illustration: Siarhei Liubimau (2019) finds that the construction of an urban settlement connected to the Ignalina nuclear power plant in Lithuania was an “essentially imperial phenomenon” (Liubimau, 2019:101). These socio-technical formations hinged upon the visions and actions of institutional actors in Moscow, who “nurtured a network of a multi-scalar essence, with very well-financed, exceptional and often secret or semi-closed urban infrastructures” (Liubimau, 2019:97).

After 1989, post-socialist economic and material transformations challenged the imperial infrastructural orders established by the Soviet Union. This new geopolitical reality was most visibly reflected in tensions concerning the governance and authority of hydrocarbon transit routes. Russian dominance across ECE, in particular, was challenged by the fact that Russia's energy exports to Europe as a whole made heavy use of pipelines that, because they “ran across the territory of certain newly independent states” were now “subject to the jurisdiction and control of the latter” (Bouzarovski and Bassin, 2011:789). The new situation also placed limits on Russian geo-energy power beyond its blizhnee zarubezhe, or “near abroad”. Despite widespread perception to the contrary, Russia was at the infrastructural periphery of the European Union and to a lesser extent even ECE itself.

A number of years ago, together with a wider group of researchers within the UK Energy research center, we explored the European gas network through a spatially relational lens (Bouzarovski et al., 2015). We found that Russia plays a relatively limited socio-technical role in the European gas system due to its geographical position in the gas supply chain and the changing nature of the worldwide gas system itself – with the latter moving towards a more globalized market dominated by trade hubs, flexible flows and “spot prices” rather than the traditional long-term supply contracts preferred by Gazprom. It is in this context that one needs to interpret the construction of the Nord Stream pipeline: it allowed the Russian state to reach deep inside the supra-national territorial assemblage of the European energy sector while reasserting a degree of control over ECE states. Yet, even with Nord Stream, Russia was not an energy superpower in Europe, although it often represented and saw itself as such. Western Europe's continued energy resilience in the wake of its complete shutdown testifies to this.

Aside from the infrastructural and spatial positionality of the Russian hydrocarbon network, I would argue that two additional contingencies have placed further limits on Russia's ability to project socio-technical power into both the ECE realm and Europe more widely. First, we need to consider the regulatory competence and might of the EU itself. This is one domain where the EU is arguably a real global superpower (Kuus, 2020), and its presence – even the promise of its presence – has led to far-reaching reforms of every aspect of the energy sector. From the 1990s and onwards, the EU's frameworks and policies accelerated the transformation of post-socialist infrastructural systems along neoliberal lines, involving, among other developments, the horizontal and vertical “unbundling” of formerly integrated state-owned energy utilities, as well as the entry of private capital in practically all aspects of the energy sector (Bouzarovski, 2009). In socio-technical and political terms, debatably, this replaced one form of infrastructural domination with another, allowing Western companies to buy up and take control of assets across the entire post-socialist space. The process, however, was both accompanied by, and led to, the consolidation and expansion of the European single energy market – and the emergence of energy security and solidarity as an EU-level jurisdiction – which in itself curtailed the ability of actors like Gazprom to wield influence throughout the energy supply chain (Mišík and Prachárová, 2016).

EU funds and interventions also aided reductions in energy demand thanks to improvements and investment in renewable energy. Nevertheless, for most ECE countries and cities they were insufficient to counter the structural effects of neoliberal energy reforms and the legacies of past housing and energy systems. Across ECE, and especially countries like Bulgaria, Romania and even some of the Baltic states (not to mention the western Balkans), “energy poverty” – the inability to secure needed levels of energy in the home (Petrova, 2018) – remains at stubbornly high levels. The reasons for this situation can be traced to many of the restructuring choices made during the post-socialist transformation. For example, after the Czech town of Liberec decided to sell off its entire local energy system and practically all other public assets to foreign investors, a direct link emerged between high energy prices and limited heating options for local residents, on the one hand, and the near-monopolistic status enjoyed by the privately-owned energy utilities in the city, on the other (Bouzarovski et al., 2016).

The second contingency relates to what some might call “everyday energy geopolitics”. Drawing upon a significant body of work in the wider domain of critical geopolitics (Dittmer and Gray, 2010; Koopman et al., 2021), I refer here to the actions of citizens but also other governance actors across multiple policy levels in relation to energy security concerns in particular. An emblematic example, for me, was how the announcement of the Nord Stream pipeline, even when the pipeline was just an imaginary construct, triggered a vast new landscape of multi-scalar discourses and physical interventions aimed at ensuring the energy security of neighboring states and particularly Poland. More recently, the grassroots “fuck Putin, ride a bike” campaign (https://errornogo.com/products/fuck-putin-ride-a-bike-sticker, last access: 24 May 2023) and concerted bottom-up initiatives to decrease domestic energy consumption to reduce gas dependency on Russia (Moussu, 2022) reflect civic mobilization to overcome systemic infrastructural legacies. Across Europe – and Central Europe in particular – we are seeing emergent networks of local energy communities and co-operatives. Many of these are built by citizens, for citizens, while using low-carbon energy resources. They actively mobilize the lexicon of energy security (Buck-Morss, 2000; Community Power, 2022).

These movements and interventions are nascent and fragile, and I am being highly speculative here about both their nature and their impact. However, it is fascinating to me, at least, as someone who has studied post-Soviet and post-socialist energy legacies for over 20 years, how radically different the current situation is to anything we have seen before within Europe. We are seeing energy solidarity with Ukraine emerge not only at the level of national governments (remembering that for a long time, energy security was not considered an EU competence, and the single energy market was sacrosanct) but also through the actions of everyday citizens. This mundane embodiment of anti-colonial energy security and transformation reflects the everydayness of energy practices that citizens of ECE experienced precisely as a result of the colonization of their region through infrastructural change.

To conclude, I have argued that energy projects are colonial not only at the Global North–Global South axis but also in relation to parts of what Martin Müller (2020) calls the “Global Easts”. The activities and legacies of Soviet domination in ECE are reflected not only in the scaffolding of the energy system, but also in the urban tissues and material fabrics of day-to-day social reproduction. The path-dependencies that underpin ECE's complex positioning within the European energy polity are the product of these interconnected dynamics, and they directly influence Europe's wider energy and climate development trajectories. In the post-Ukraine invasion era, they have brought attention to the possible horizons for energy system transformation – from sites of production to practices of demand (Balmaceda et al., 2019) – through emergent forms of everyday geopolitics. This is where we start to see the breakdown of colonial structures, not only in terms of transnational geo-energy reconfigurations, but also through the power of grassroots citizen action. Illuminating the spatial articulations and limits of energy imperialism has a significance that extends beyond the immediacy of the current crisis in Europe. We have been seeing how another hegemonic power – China – is actively seeking to shape global, regional and local infrastructural landscapes through its own specific modes of urbanization and development (Apostolopoulou, 2021; Wei Zheng et al., 2023). These socio-technical and geo-economic strategies remain even less recognized and understood than Russian infrastructural colonialism. But with the unfolding of recent events in Ukraine and Europe more broadly, at least we cannot say that we have not been warned.

The relevance and timeliness of the theme that Stefan Bouzarovski addresses are difficult to overstate. Energy is at the nexus of the multiple crises that Europe – and not just Europe – currently faces: climate, humanitarian and geopolitical. At the heart of this are the networked energy infrastructures that extend across Europe and the overlapping and shifting geopolitical configurations that shape Europe's energy geography. Stefan's intervention develops this theme by carefully examining the colonial past and present of these energy infrastructures against the background of geopolitics – from the everyday mundane to the world stage.

My first reaction to Stefan's paper was to try to put Switzerland into the picture – or, perhaps better, on the map that Stefan was laying out before us. In 2022, the energy crisis also arrived in our country. We were announced possible energy shortages, unprecedented in the land of plenty that Switzerland has been for at least 70 years. My neighbor started hoarding firewood in the basement to feed his self-installed wood stove and kindly invited his neighbors to come to his flat during weekends to warm ourselves up. During summer, the news reported that the number of electric heaters sold had gone up massively, threatening to result in a blackout scenario, locally also called “Öfeli-GAU” (Swiss German for: heater worst-case scenario) (Aebi, 2022). Personally, and having experienced many Öfeli-GAUs during a winter spent in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, I considered buying a voltmeter to determine the best moments for doing laundry and baking cake. But then I learned that the Swiss grid will be shut down rather quickly without allowing the voltage to drop. Eventually, we received an all-clear signal for this winter from the Swiss government, the blackout scenarios did not materialize, and the energy shortage was hardly felt in the end.

On first thought, all this reflects Susan Leigh Star's (1999) famous statement that infrastructure becomes visible solely upon breakdown – in this case, an anticipated one. Infrastructure's invisibility fades away when it breaks. But I would like to probe both the nature of this invisibility and its rupture a bit further. First, the invisibility. Had I ever actually thought about the origins of the gas that flows freely into my apartment for cooking hot meals, taking hot showers, and making myself feel cozy and at home when I close the door to the outside after a long dark winter day? Frankly, before this spring, I had not. Only the war in Ukraine brought this to my mind and finally drew my attention to the flows of gas as flows of power that connect my very private home to the larger energy infrastructure and geopolitical configurations that Stefan describes. For the case of Berne, where I live, 50 % of the gas is provided by Russia. Warm meals, hot water and a heated flat are embedded in and the product of a particular geopolitical configuration, and that configuration is about to shift.

Swiss society has never been particularly inclined to take a closer look at the origins of its wealth, safety and comfort. These are usually framed as achievements and attributed, to a lesser or greater degree depending on political orientations, to the hard-working and dexterous nature of the Swiss people. Of course, this may be the short-sighted mundane horizon of people in capitalism's rat race that leaves little time and leisure for stepping back. But I would argue that such a view has also much to do with Swiss elites' hegemonic masking of the actual political-economic system based on relations of force that produce these privileges. Yet from time to time, history tends to present us with these moments of “unpleasant surprises”, when we can no longer ignore the often highly problematic origins and sources of our well-being. Such an instance was the 1995 revealing of Switzerland's collusion in the crimes of Nazi Germany and Holocaust victims' assets deposited in Swiss banks, which deconstructed narratives of “neutrality” during World War II. The war in Ukraine made it clear that Swiss geopolitical and geo-economic entanglements continue, even if the prevailing narratives may divert our attention from them.

Stefan's paper speaks of Russia's self-defined “imperial innocence” (Kassymbekova and Marat, 2022), framing its rule of non-Russian people not as colonialism but as a gift of greatness that demands eternal gratitude. Undoubtedly, this is an important and recently challenged hegemonic imaginary that underpins Russian supremacist ideology. It is ironic, though, that Ukrainians fleeing from the horrible consequences of this ideology to Switzerland are again confronted with expectations of eternal gratitude: they should be grateful for Swiss hospitality that, in many Swiss people's understanding, is offered by a country completely disconnected from the war. The manifold ties that Switzerland does have with Russia through its financial sector, the commodity trade firms it is hosting – including hubs and operations by the Russian Gazprom – and the safe haven for the ultra-rich it offers are rarely considered. In blinding out these connections, the Swiss may even assume that Ukraine should rather accommodate the Russian aggression for the greater good of the continuity of former arrangements which guaranteed our privileged lifestyle (Balmer, 2022). It occurs to me that the term “imperial innocence” applies as much to Switzerland as it does to Russia, although in a different form. Most Swiss people stubbornly cling to the belief that Switzerland has nothing to do with colonialism. No glory, no guilt. The individual instances that occasionally pop up, almost rhizomatically, and disturb our – shall I say – blissfully ignorant complicity are still taken to be unfortunate exceptions. Stefan's paper, however, encourages us to think more systematically not just about Switzerland's hidden coloniality, but also about the inter-imperiality that shapes geopolitical configurations and manifests in highly paradoxical instances of two-sided framing of Ukrainian guilt and expectations of gratitude.

Stefan's paper outlines the relationships of obduracy and change that inform the energy infrastructure in Europe with the ongoing reconfiguration of energy provision. In relation to this, it is worth taking a closer look at the theme of rupture in the form of discursive turbulence that the recent shifts have created. During the summer of 2022, fake ads appeared in Switzerland's public space, offering a telephone number to tell on neighbors who were suspected of heating up their apartment above the prescribed 19∘ (recently raised to 20) (McEvily, 2022). Russian state media gloatingly commented that Europeans who were afraid of sitting in dark cold flats during winter were offered the alternative to come to Russia where heating is plentiful. Recently, a Swiss-based Russian journalist's statement that Swiss citizens are asked to stock food to ward off an anticipated food crisis was circulated by Russian media – truthfully mirroring Soviet agitprop style (Reichen, 2022). While these instances may be anecdotal and even amusing, I suggest that they point to another important dimension raised in Stefan's paper: the relations between everyday geopolitics and forms of energy governance.

Clearly, energy provision has been and is a strategy of political stabilization in the Soviet Union and its successor states. Take, for example, Central Asia, where cheap electricity is arguably the most important state subsidy to citizens – more or less reliably delivered. The mostly authoritarian leaders of these countries take great care in fine-tuning their countries' energy systems in order not to jeopardize the political stability that depends on this basic provision. Yet Stefan's paper also reminds me of an influential book that I had read years ago during a postdoctoral fellowship in Singapore: Cherian George's (2000) edited volume “Singapore: The air-conditioned nation. Essays on the politics of comfort and control, 1990–2000”. The collection of essays discusses, both literally and metaphorically, the importance of cooling as a technology of authoritarian rule in the island state during the 1990s. Stefan's paper shows that not just cooling, but also heating should be considered as a form of political and technological power that plays out from the world stage to everyday geopolitics.

To conclude, Stefan's intervention provides an inspiring and stimulating entry point to rethink Switzerland's position and, indeed, positionality in the networked infrastructures and shifting geopolitical configurations of Europe's energy geography. It draws attention to the highly unequal power relations that both shape and feed on the flow of energy, as well as to our very personal everyday complicity with current arrangements.

In his essay, “Russia, Europe and the Colonial Present”, Stefan Bouzarovski surfaces in an insightful way what I would call the underlying “energopolitics” (Boyer, 2014) of the Russia–Ukraine war. Energopolitics are the web of sociomaterial relations linking energy systems to political institutions. As in Timothy Mitchell's pathbreaking study of the entanglement of coal and social democracy – or “carbon democracy” as he puts it (2009) – energopolitical analysis helps us to see how struggles over energy resources, and the conditions of possibility set by their material forms, can exert potent yet seemingly invisible force over political dynamics and ideas.

Bouzarovski argues convincingly that Soviet colonial legacies of energy have been reactivated in Putin's Russia. Putin has shown increasing willingness to wield fossil and nuclear fuel energy exports as a “geopolitical weapon” to extend Russian political influence, especially in eastern Central Europe. By their own admission, several European nations, notably Germany, underestimated Putin's interest in weaponizing energy exports, assuming instead that energy sales would help Putin fund the ongoing democratization and global market integration of Russia or that establishing critical trade relationships between Russia and the EU would at least reign in his regional imperial ambitions (Wintour, 2022). Putin's aggression in Ukraine has always involved energy resource motives, with one observer arguing that “Putin's annexation of Crimea was very much driven by undermining Ukraine's energy and gas diversification strategy” (Umbach, 2014). Indeed, the government Putin installed in Crimea immediately entrusted Gazprom to manage the peninsula's energy sources.

Yet what happened in Crimea only scratches the surface of a very complex energopolitical situation. Even before the Maidan Revolution and Victor Yanukovych's ouster, a struggle over gas imports was brewing. Although Yanukovych's government is normally glossed as “pro-Russian”, in only 2 years (2011–2013) it presided over a 37.8 % decrease in Russian gas imports (Umbach, 2014). Worse still, the 2010 discovery of the Yuzivska field in Donestk and Kharkhiv oblasts threatened Russia with eventual Ukrainian independence from Gazprom. Though its resources would require unconventional techniques like fracking to be accessed, the Yuzivska field has been estimated to contain over 2 trillion cubic meters of gas reserves (Tully, 2015), the third largest deposit in Europe (Coalson, 2013). With the near depletion of Ukraine's conventional gas fields, the development of Yuzivska held the potential to substantially rebalance energy relations between Kyiv and Moscow in the decades to come. Although Russian firms bid for the exploration and production partnership, Yanukovych's government announced in 2012 that Royal Dutch Shell and Chevron had been chosen as the project partners for its largest shale gas fields, including Yuzivska (Reuters, 2012). This move to embrace Western partners was likely unsettling for Putin and his Gazprom allies, and shortly thereafter they took advantage of the revolutionary moment in Ukraine in 2014 to move the battlefield closer to the gas field (Umbach, 2014). Within a year both Chevron and Shell had pulled out of their partnerships “because of the fighting in the region and prospect of little profit from the project” (Tully, 2015).

Tellingly, the energopolitical dimension of the war in Ukraine continues to be downplayed today in reporting and analysis. The brutal conflict over the town of Bakhmut at the time of this writing in early 2023 is an excellent case in point. News media coverage suggests that the intense fighting near Bakhmut and tens of thousands of deaths over the past 6 months are best explained, on the Russian side, as a case of the Wagner Group seeking to prove its ferocity and operational value to Putin and as a matter of national pride and show of defensive tenacity for the Ukrainians. The geographic specificity of Bakhmut is rarely mentioned as compared with commentary on what performing military prowess means to both sides (e.g., Bertrand et al., 2023). As a recent Reuters (2023) analysis puts it, “The town has symbolic importance for both Russia and Ukraine, though Western military analysts say it has little strategic significance” (Reuters, 2023).

Mere symbolic importance is a very curious conclusion since, geologically speaking, Bakhmut's significance is substantial. The Bakhmut Depression is the southeastern edge of the Yuzivska field (Panova and Pryvalov, 2019). That the bloodiest section of the Russian–Ukrainian front line is the exact edge of Ukraine's most important gas frontier seems hardly a coincidence. Control over the Yuzivska field would considerably strengthen Putin's strategy of weaponizing Russia's gas exports. Even rendering Yuzivska a militarized no-man's-land or ruined waste could set Ukraine's movement toward energy sovereignty back for decades.

It would be an oversimplification of course to suggest that energopolitics are the only explanation for Russia's recent aggression in Ukraine. Ukraine has other resources that Russia eyes avidly, including its agricultural outputs. Even beyond his general imperial ambitions, Putin seems to hold a particular animus against Ukrainian sovereignty, arguing famously that modern Ukraine was a product of the Soviet era that now needs to be restored to its cultural and economic wholeness with Russia (Putin, 2021). Moreover, it is no secret that authoritarian regimes across the world (and through time) utilize wars to cement popular support (de Mesquita and Siverson, 1995), generating political identity and sympathy through the demonization of neighbors, victim narratives, and the experience of shared sacrifice. There is also the matter of, according to Putin, security concerns about NATO's eastern creep and Zelensky's post-invasion openness to joining the European Union. Still, as Bouzarovski's essay demonstrates, an energopolitical lens helps to reveal much about colonial relations both past and present.

Another aspect of Bouzarovski's analysis that I find intriguing is his argument that Russia is in reality not quite the “energy superpower” it imagines itself to be. Russia not only overestimated its military capacity to subdue Ukraine quickly but it also underestimated the “energy solidarity” that other European countries were willing to show Ukraine by price-capping and limiting or banning Russian oil and gas imports. The financial impact has been substantial especially in recent months as oil prices declined from their peak in June 2022. According to a study by CREA (https://energyandcleanair.org/publication/eu-oil-ban-and-price-cap-are-costing-russia-eur160-mn-day, last access: 30 May 2023), the EU oil ban and price cap are costing Russia an estimated EUR 160 million per day.

Yet, at the same time, even depressed Russian oil revenues remain very substantial, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA) as much as EUR 15.8 billion in November 2022 alone (Lawson, 2022). As the world's third largest petroleum producer and second largest natural gas producer, Russia remains an extremely important player in global energy markets and for all intents and purposes a petrostate. Although Russian fossil fuel exports to Europe have scaled back dramatically, it is still selling its oil, especially to India, China and Turkey, all of whom are taking advantage of sanction discounts. India alone bought 33 times more Russian oil in December 2022 than a year earlier, making Russia India's main fossil fuel supplier (Sharma, 2023). So long as Russia can find avid buyers of its oil outside Europe, and so long as oil remains the lifeblood of the global economy, it is difficult to consider Russia to be anything less than a global petropower.

However, I take Bouzarovski's point as rather that after the Ukraine war, Russia will likely never again be able to wield the same energopolitical influence as it has previously in Europe, even eastern Central Europe, beyond a few stubborn outliers like Hungary and the Slovak Republic. Part of this reasoning has to do with technical and market developments, especially concerning natural gas. Gas markets in the era of liquefied natural gas (LNG) are less pipeline dependent than they have been in the past. European countries now have every incentive to make sure that they create sufficient LNG infrastructure to avoid ever having to rely on Russian gas imports again. Short of radical regime change in Moscow in the near future this seems a trend likely to reshape European energy markets decisively.

Even more significant, one hopes, will be the impact of what Bouzarovski calls “everyday energy geopolitics” or what I might call “energy citizenship”, in other words, the intensification of civic activity around matters of energy efficiency and energy transition. The case of the electrification of the automobile sector is a well-known example. Global electric vehicle (EV) sales doubled in 2021 and are beginning to seriously contest internal combustion engine vehicles for market share in parts of Europe and Asia. The growth rate is actually staggering. In Germany in July 2022, EVs accounted for 14 % of new passenger auto registrations. By December 2022, they accounted for 33.2 % (https://cleantechnica.com/2023/01/08/evs-take-55-of-the-german-auto-market-in-december/, last access: 30 May 2023) of new registrations. Less known but equally critical is the case of electric heat pumps since one-third of European gas demand relates to heating buildings. According to a recent IEA report (https://www.iea.org/news/the-global-energy-crisis-is-driving-a-surge-in-heat-pumps, last access: 30 May 2023), annual sales of heat pumps could more than triple in Europe this decade, reducing gas demand by nearly 7 billion cubic meters by 2025. Whether or not the Ukraine war has been a decisive catalyst shaping consumer behavior is unclear. Yet at the very least Putin timed his gamble to weaponize fossil fuel supplies poorly. Europe had already built substantial momentum behind efficiency and electrification ventures before the 2022 invasion, and activity in the past year seems to have only accelerated these trends. Every unused barrel of oil and cubic meter of natural gas spared takes ammunition away from Putin's fossil war machine. Yet it is important to recognize that because oil and gas can be so easily rechanneled to avoid embargoes and other kinds of political pressure, it is crucially important that energy citizenship needs to be coordinated and transnational in much the same way that the oil and gas industry has been for over a century (Mitchell, 2009).

In closing, I wish to caution that petrostates are exceedingly resilient. We underestimate at our own collective peril petrostates' survival instincts and willingness to use violence to maintain their hegemony. In the United States – itself a petrostate in my reckoning (Boyer, 2023) – the oil and gas industry deploys a powerful collection of instruments to make the fossil status quo seem both inevitable and desirable. It is truly an “all of the above” strategy: from funding anti-science climate denialism, to capturing political institutions and parties, to championing phantasmatic boondoggles like carbon capture and grey hydrogen technologies that inhibit investment in genuine alternative energy pathways, to planning a hard swerve toward petroplastics as a final emergency off-ramp. All of these instruments directly and indirectly aid the cause of petrostates like Russia by continuing to hold the global economy in the thrall of fossil fuels.

Change is coming, there is no denying that any longer. Just as incandescent light bulbs went from 68 % of the US market to 6 % in only 6 years (https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/03/08/climate/light-bulb-efficiency.html, last access: 30 May 2023), the need for fossil fuels may even disappear more quickly than we believe is possible today. However, in the meantime, we should be prepared for more, not less, energopolitical violence emerging on the frontiers of change. Oil and gas will not go quietly.

Stefan Bouzarovski's article is highly informative when it comes to understanding the power-shaped history of energy infrastructures in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) constructed during the Cold War era and their legacies. In the final paragraphs of his intervention, Bouzarovski then mentions “emergent forms of everyday geopolitics”, or “actions of everyday citizens”, that started to appear in post-socialist CEE in response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2022. He mentions, specifically, grassroots campaigns or bottom-up initiatives to decrease domestic energy consumption, aiming to reduce dependency on Russia as well as to express “energy solidarity” with Ukraine. Next to other areas where “energy system transformation” may occur, Bouzarovski sees such citizen actions as one possible way forward to overcome systemic infrastructural legacies that reflect the history of Soviet domination in the region. However, he is careful not to assume and/or overstate the “nature and […] impact” of these interventions. Still, his statements, which he calls “speculative”, are worth further exploration. For example, his observations provoke reflections about the complexity of processes through which practices of individual energy consumption change and which may eventually influence how (quickly) dependencies established during the socialist era can be reversed. Namely, it is reasonable to focus on the multiple motivations that lie behind shifts in everyday routines as well as various constraints on or opportunities for changing one's behavior.

In this commentary, I underline this complexity to point out that some facets of “energy system transformation” in post-socialist CEE happening on the level of everyday life and as part of households' daily reproduction may take place indirectly, unintentionally or at least “inconspicuously” (Ferenčuhová, 2022; Shove and Warde, 2002), while others are straightforward in their political motivation – like those expressed in grassroots campaigns. Moreover, some clear-cut intentions towards change may be difficult to put into practice by individual households given their economic situation, household structure and relations between their members but also the material environment, including the existing energy infrastructures upon which they already depend.

I focus here on the Czech Republic, one of the Central European post-socialist countries. According to information recently published by the Energy Regulatory Office, Czech households consumed 20 % less gas in 2022 than they did in the previous year (ERO, 2023). The debates that started after February 2022, however, went beyond reducing individual energy consumption in solidarity with Ukraine, although these were certainly present. For example, local groups of international movements like Greenpeace or Extinction Rebellion included limiting room temperature in homes on their lists of strategies available to individuals to reduce dependence on Russia's raw materials and support Ukraine, together with other environmentally friendly practices to decrease energy consumption (Extinction Rebellion, 2022; Hrábek, 2022). Another response came from two students of medicine in Brno. Their individual initiative “Throw on a Jumper” called upon people to heat their homes less, wear more clothes and share their pictures on social media to spread the message (Koudelová, 2022). The argument was also adopted by others, for example, by the Ministry of Industry and Trade who motivated households to adopt saving measures and designated them as a strategy in the “energy war” (Janouš, 2022).

However, rising prices also made many households insecure about the amount that payments for gas and, more generally, energy would represent in their budgets. According to a recent survey that mapped shifts in consumption practices in the months following Russia's invasion of Ukraine, 69 % of Czech households had adopted some measures to reduce their energy expenses by December 2022 (for example, lowering room temperature, heating only some rooms, avoiding using energy-intensive appliances or insulating the home) (Focus Agency, 2023). The same survey found that Czech households have widely felt the impact of rising prices: 43 % declared that they needed to limit their consumption to meet their needs, including 10 % of households that could not meet their basic needs with their current income and needed to use their savings or borrow money. The way people shopped for groceries or cosmetics, not just how they used energy, also changed (Focus Agency, 2023). Thus, unsurprisingly, the changes in everyday practices towards lower energy consumption that Czech households have declared to have introduced in the past year inevitably reflect, and sometimes combine, both a political response to Russia's invasion of Ukraine and prudence and/or an economic necessity.

Various motivations aside, what households can actually do to save energy is also conditioned by many factors. For example, low income does not easily allow for the adoption of energy-saving measures that require new investments, such as insulating roofs or walls, installing solar panels, or acquiring new appliances and technologies, even if some financial support may be available at municipal or national levels. Moreover, economic hardship complicates individual support for political decisions, like ending Czechia's consumption of gas imported from Russia, should this mean rising prices (Focus Agency, 2022:29–30). Next, household structure, relations between its members and their everyday routines all influence how households consume energy (e.g., Bell et al., 2015; Strengers et al., 2016; Madsen, 2018). Moreover, material conditions also play a role. For example, households dependent upon centralized district heating systems – mentioned by Bouzarovski as one of the principles of Soviet housing planning, which is based on the concept of mikroraion and adopted widely in Central and Eastern Europe – such as residents of individual flats in large 1970s and 1980s housing estates have fewer options to change or diversify the sources of energy they consume than, for instance, owners of detached single-family houses do in small settlements (where infrastructure like district heating is often not even available). Hence, systemic infrastructural legacies of the Soviet era in post-socialist CEE that influence how and what energy resources are used in Czech households vary – according to housing type, year of construction and type of reconstruction as well as its location in a municipality, the settlement size and the settlement's position in the region. All of this influenced how energy infrastructure historically developed and how today's individual households are connected to and dependent upon it (see, e.g., Bouzarovski et al., 2016). Yet, it also constrains or enables capacity among individual households to bring about change to the existing energy system through their everyday practices alone (mainly by saving energy, changing energy sources and adjusting the materialities in their homes).

In summer 2022, I was intrigued by saving (and energy-security) strategies adopted by one household I knew. Living in a house built in the first decades of the 20 century and using gas for heating, the family made several changes to the organization of their home, such as altering the uses of some rooms so that parts of the house could remain unheated (or at least less heated) during winter. In addition, the family invested in a fireplace, installed in the living room. To do so, they reconstructed a chimney connection that had been hidden from sight for several decades and thus reintroduced technology, and an energy source, that was used in the house by previous generations. The fact that the chimney and the connection were already in place (as part of the house's “historical infrastructure” but currently out of use) made the adjustment easier. Their decision to install the fireplace and use wood as a secondary heating source was not entirely random. The family mentioned at least four other households they knew of, all living in small settlements, that had made similar investments. Moreover, in 2021, wood was already the most common secondary energy source used by households that consumed gas as their primary energy source (CSO, 2022, Table 3-3.2).

It is important to note that adjusting one's housing for more cost-efficient living is not generally new to the Czech Republic. Renovations of the housing stock, including insulation or thermo-insulating windows, have been widespread in recent decades. In 2021, according to a survey in Czech households, 21.4 % and 7.5 % of the housing built before and after 1970, respectively, were left without any similar measures (with thermo-insulating windows being the dominant measure, however, while roof and wall insulation is less common) (Matějka and Štech, 2022).

Additionally, in the CEE, household practices that contribute (at least a bit) to saving different types of resources or that are “quietly sustainable” (Smith and Jehlička, 2013) are also relatively common, and some of them have been in place for quite some time. To name just a few, Czech households engage in producing and sharing food (Jehlička and Daněk, 2017), tend to reduce food waste (89 % of households in 2022; see Focus Agency, 2023; Jehlička, 2022), or repair old things (64 % of households; Focus Agency, 2023). A tendency not to waste water or energy in situations like heat waves and drought and instead coming with simple, energy-efficient everyday adaptations is also not unusual (Ferenčuhová, 2022).

Thus, the action and practice repertoires that eventually helped to reduce Czech household consumption of gas by one-fifth in a year (namely everyday savings, turning to other energy sources and/or insulating the house) were mostly “available” or considered prior to Russia's invasion of Ukraine and were culturally acceptable. Nonetheless, at least in some cases, these actions were prompted by the events of 2022, perceived as either a political, economic or security issue or a combination thereof.

The simple point that I want to make in response to Bouzarovski's thought-provoking intervention, therefore, concerns one aspect of everyday geopolitics that can easily slip by unnoticed, as the practices are too mundane, routine, variously conditioned, questionably relevant and inconspicuous. Importantly, though, the straightforward aim to contribute to more systemic change, such as reducing the country's dependence on non-renewable resources, does not need to be reserved for people joining movements or initiatives like those mentioned above. Nor is it unusual that motivations are complex and economic goals easily combine with other aims, environmental or political, in one household. Yet, the geopolitical effect of everyday practices, and their impact on infrastructural legacies, may appear even if the stimulus of their change is not so clear. Bouzarovski mentions “emergent forms of everyday geopolitics”, the first signs of the “breakdown of colonial structures, not only in terms of transnational geo-energy reconfigurations, but also through the power of grassroots citizen action” (Bouzarovski, this forum, Sect. 1). In order to understand the complexity of such transformation, I suggest including in this picture everyday routines and practices, which is not so straightforward in naming the issues of energy security and that may not even reflect the issue at all. Indeed, they may both enable as well as complicate the entire process.

When the troops crossed the Ukrainian border on 24 February 2022, Russia conclusively decided to “resurrect history” in its relations with the West in a move that blatantly unveiled the country's neo-colonialist ambitions. Undemocratically elected president and war criminal2 Vladimir Putin wanted Russia to be recognized as a great, not just regional, power, first by proposing a set of unrealistic demands on the West in exchange for appeasement and subsequently by setting off a war of territorial conquest the likes of which Europe had not seen since World War II. At this point, the Kremlin crossed a propagandistic Rubicon towards which it had been moving for at least a decade, its perception and representation of the West having evolved from that of partner to that of diabolical enemy, passing through the intermediate stages of competitor, rival, “partner” (with scare quotes) and adversary (see, e.g., RIA Novosti, 2022). In doing so, Russia pivoted from its previously successful strategy of geo-economic and “socio-technical” colonialism, whose characteristics are convincingly described by Stefan Bouzarovski in his opening contribution, towards one based on the imposition of brutal force.

Some, including myself, would argue that the point of no return was already reached in February 2014, when Russia occupied Crimea and unleashed its war on the Donbas. However, at that time, the response from the West was timid: the hearts and minds of most of its politicians were not yet ready to absorb the new reality created by this event, and besides, how could anyone survive without Russia's vast hydrocarbon resources? Some sanctions were “slapped on” the country, but otherwise, business as usual prevailed. Mild castigation was chosen before deterrence, and an aggressive outburst set within a pattern of autocratic consolidation was treated as a one-off event, hesitantly, and against the background of the increasingly cacophonic and polarized politics in the EU.

Meanwhile, Russia continued its journey towards the dead-end of neo-colonialism by increasingly striving to delegitimize the sovereignty and statehood of its neighboring countries and of Ukraine in particular. This process culminated in the aforementioned war criminal's notorious “historical essay” published on 12 July 2021 on the Kremlin's website (Putin, 2021), which makes a number of points that – in hindsight for some, in foresight for others – outline the contours of Russian neo-colonialism and of its justifications in the 21st century, which are the following3:

-

The sovereignty of Ukraine (and indeed of most if not all other former Soviet republics) is illegitimate and that the authors of “the right for the republics to freely secede from the Union […] planted in the foundation of our statehood the most dangerous time bomb, which exploded the moment the safety mechanism provided by the leading role of the CPSU was gone”. Accordingly, “modern Ukraine is entirely the product of the Soviet era”.

-

Ukraine was “shaped – for a significant part – on the lands of historical Russia”, meaning that the Ukrainian territory is rightfully Russian.

-

“Russia was robbed” by the Bolsheviks, who were “generous in drawing borders and bestowing territorial gifts” because they believed in a world without nation-states.

-

Russia and Ukraine are an inseparable economic unit whose “profound cooperation […] 30 years ago is an example for the European Union to look up to”.

-

Ukraine is not truly sovereign and that it is exploited by “external patrons and masters” as an “anti-Russia” for these actors to achieve their geopolitical goals of Russian containment. Indeed, as the war criminal explains, “the Western authors of the anti-Russia project set up the Ukrainian political system in such a way that presidents, members of parliament and ministers would change but the attitude of separation from and enmity with Russia would remain”.

-

Ukraine is “Russophobic”.

-

Russia as a state is a victim of Western (American) machinations and that Russians in Ukraine “are being forced not only to deny their roots, [and] generations of their ancestors[,] but also to believe that Russia is their enemy” to the extent that “the path of forced assimilation, the formation of an ethnically pure Ukrainian state, aggressive towards Russia, is comparable in its consequences to the use of weapons of mass destruction against us”.

-

The residents of southeast Ukraine “were threatened with ethnic cleansing”.

-

Ukraine is not interested in the fate of the people of the Donbas (in any case) and that it merely needed the conflict to sustain the “anti-Russia project, [which required] the constant cultivation of an internal and external enemy […] under the protection and control of the Western powers”.

-

Russia “will never allow [its] historical territories and people […] living there to be used against Russia” and that anyone attempting to do so would “destroy their own country”.

-

The “true sovereignty of Ukraine is possible only in partnership with Russia, […] for we are one people”.

In short, the Russian war criminal accuses an ostensibly inexistent Ukraine and its alleged Western mentors of the very same crimes that Russia itself has been committing on Ukrainian soil for nearly a decade, while suggesting that Ukraine “exploits the image of the victim of external aggression”. Such claims are neither novel nor surprising for anyone versed in the parallel and increasingly remote universe of Russian propaganda which aims at portraying Russia as a besieged fortress surrounded by enemies hellbent on destroying the country (Yablokov, 2018). Victimhood is thus Russia's first justification for its “special military operation” in Ukraine.

The second justification is more traditional in its defense of colonialist practices. As Stefan Bouzarovski explains, Russia sees itself as both a civilization reference point and a great modernizer for its colonial subjects. A central trope in Russian neo-colonialist discourse is that Russia “created” rather than conquered its surrounding nations and that the latter are unable to survive, let alone prosper, outside of Russia's custody. However, by having “created” most post-Soviet republics, the Kremlin also implies that these states are Russia's offspring, that their sovereignty is limited and that the legitimacy of their statehood falls short of, e.g., France's or Norway's.

The third justification is that Russia is taking back what was unjustly taken away from it. The Kremlin's rhetoric increasingly suggests that Ukraine is “artificial” and that it was (unfairly) carved out of what is, in fact, Russian land, implying that the country has no right to exist at all. By concluding that Russians and Ukrainians are “one people”, by systematically failing to mention Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky by name, and by constantly repeating that the country is ruled by external “patrons and masters” (because of it being controlled by the West), the Russian war criminal is in fact suggesting that Ukraine consists of Russian land occupied by foreign forces, hence the narrative that Russia is not at war with Ukraine but with the West. In his own words a few weeks ago “[the West] started the war, while we have used and are using force to stop it” and “[Russia is] defending the lives of people, our own homes, [but] the goal of the West is unlimited power” (Putin, 2023, my translation and emphasis).

Where the war criminal's words stop, the state media's begin: by increasingly invoking dehumanizing language, Moscow's chief propagandists – Margarita Simonyan, Vladimir Solovyov, Olga Skabeyeva and Dmitry Kiselyov – are instrumental in creating the conditions for the Russian population's acceptance of its government's genocidal policies. “When a doctor is deworming a cat” – Vladimir Solovyov explained on prime-time television – “for the doctor, it's a special operation, for the worms, it's a war, and for the cat, it's a cleansing” (Cole, 2022). Another Russia Today (RT) propagandist, Anton Krasovsky, went as far as to suggest that Ukrainian children should be drowned or shoved into huts and burned (Roth, 2022). While these statements are extreme in their explicitly genocidal rhetoric, they merely represent an escalation of an established Russian media trend. In 2014, when Channel 1 (Pervyi Kanal) anchor Dmitry Kiselyov exaltedly declared that “Russia is the only country in the world that is realistically capable of turning the United States into radioactive ash” (Kelly, 2104), this was mostly viewed as empty rhetoric aimed at exciting the domestic masses. Nowadays, calls to “nuke” the West are made regularly and have long ceased to raise eyebrows.

To conclude, despite having unleashed a war of re-colonization against Ukraine, Russia tries to brand itself as the leader of the global decolonial movement, a role it recycles from the years of the Cold War when the Soviet Union capitalized on the resentment felt against former colonial powers in many parts of the developing world (McGlynn, 2023). This contradiction finds its perverse (propagandistic) resolution by relying on allegations of Russian victimhood, by reminding everyone that Russia did not have any colonies when other countries did (which is, mildly speaking, debatable), by promoting Russian civilizational leadership and superiority in comparison with the “decadent” West, by denying the existence of Ukraine's statehood, and, ultimately, by dehumanizing its inhabitants through increasingly unhinged genocidal rhetoric. Ukrainians are either “us”, as in Russian, or they are at the service of the West. The latter must therefore be “de-nazified” and their children drowned or burnt.

This contribution to the debate on Russia, Europe and the colonial present brings together several closely linked events which – alongside the people participating in them – have unleashed enough kinetic energy to kill and maim hundreds of thousands of people in just 12 months. Being inspired and challenged, in equal measure, by Stefan Bouzarovski's intervention on the lasting power of energy colonialism, my aim here is to expose the key features of contemporary Russian imperialism as a concept and the Kremlin's professed lust for territorial expansion and colonial domination as a practice. The empirical vignettes described below are assembled to uncover this exemplar of imperialism and colonialism as a theory-to-practice dyad. They involve (a) a 2021 sketch of pseudoscientific “thermodynamic” theory of imperial geopolitics pencilled by the Kremlin's chief adviser on Ukrainian affairs, (b) a 2016 televised geography lesson from the chairperson of the Russian Geographical Society's board and (c) an original operational plan for achieving control over Ukraine drawn by Moscow in the run-up to its full-scale invasion on 24 February 2022.

6.1 Thermodynamic imperialism of Vladislav Surkov: towards unrestricted expansion

Three months prior to the Russian invasion, Vladislav Surkov, the former first deputy chief of the Russian Presidential Executive Office (1999–2011), deputy prime minister of Russia (2011–2013) and a special adviser of President Vladimir Putin on relationships with Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Ukraine (2013–2020), published a piece entitled “Where has the chaos gone? Unpacking stability”. In his article, Surkov (2021) – the most creative and influential of the Kremlin ideologues and mastermind of Moscow's attempt at creating a New Russia (Novorossia) puppet state in southeastern Ukraine in 2014 (Mykhnenko, 2020; Suslov, 2017) – has sketched out his theory of imperialist geopolitics.

Unlike the late 19th–early 20th century founding fathers of geopolitics, e.g., Friedrich Ratzel and Halford Mackinder, who appealed to evolutionary Darwinist notions of the state as a biological organism necessarily expanding in its growth (Kearns, 2009; Klinke, 2018), Surkov's geopolitics is rooted in thermodynamics. According to the second law of thermodynamics, a physical law cited by Surkov as the basis for his pseudoscientific musings, the entropy of an isolated system always increases as the system evolves towards thermal equilibrium: no system operating in a closed cycle can convert all the heat absorbed from a heat reservoir into work, leading to an increase in entropy of the universe (entropy production) that results from this inherently irreversible process (Jelley, 2017; Park and Allaby, 2017). Jumping from the realm of physics to human evolution and back again, Surkov offers an allegedly scientific solution for dealing with Russia's increasing total entropy – interpreted as social malaise, lack of order and chaos and understood as an inherent and irreversible phenomenon present in all (closed) systems. His radical policy proposal harks back to Joule's free (unrestricted) expansion, a thought experiment in classical thermodynamics involving ideal gases, during which (1) a gas completely fills the vessel or chamber in which it is kept, and (2) when the valve between two adjacent chambers, initially closed, is opened, (3) the gas irreversibly expands into an evacuated insulated chamber, completely filling it, too, as a result (Escudier and Atkins, 2019). In a similar vein, Surkov argues the following (emphasis added):

Social entropy is very toxic. It is not recommended to work with it at home. It needs to be taken somewhere else, transferred for usage into an alien territory. Exporting chaos is nothing new … It is a discharge of internal tension (which Lev Gumilev vaguely called passionarity) through external expansion. The Romans did it. All empires do this. For centuries, the Russian state, with its harsh and sedentary political interior, was preserved solely thanks to the relentless striving beyond its own borders. It has long forgotten how and, most likely, never knew how to survive in any other way. For Russia, constant expansion is not just one of the ideas, but the true existential of our historical existence … Russia will expand not because it is good, and not because it is bad, but because it is physics. (Surkov, 2021)

Just 9 days before Russian tanks rolled across the Ukrainian border on the way to Kyiv, Surkov had published another piece – this time about getting ready for the return of “geopolitics in its original form”. Despite his many post-modernist fictional, poetic and dramatic stage exploits, Surkov's last pre-war intervention was unvarnished, Ratzelian Lebensraum.

Territory size matters. Control over space is the basis of survival … Hence, there is a lot of geopolitics ahead: practical and applied, and even, perhaps, of contact type. But how could it be otherwise, if one is crammed and bored, and awkward … for it is unthinkable for Russia to remain within the boundaries of this obscene world/peace4. (Surkov, 2022)

To note, Surkov's thermodynamic theory of Russia's gas-like unrestricted expansion was published in an in-house online magazine of his pet private think tank called The Foundation Centre of Political Conjuncture. In the early 2000s, this think tank was made famous when its inaugural director – Konstantin Simonov – published two volumes of conservative geopolitics concerning the Russian oil and gas sector and the “upcoming” and “inexorable” conflict over the world's dwindling hydrocarbon fuels entitled The Energy Superpower (Simonov, 2006) and A Global Energy War: Secrets of Modern Politics (Simonov, 2007). Written in a fairly conspiratorial and accessible fashion, these sensationalist bestsellers warned the Russian leadership directly to get ready for an imminent Western “Crusade for Oil and Gas”. The new global energy war will be waged by the USA and the European Union, forming an aggressive “Energy NATO”, and flanked by India and China, another two “hydrocarbon sharks”, which will attack the nations rich in “black gold” and “blue fuel” – invoking Mackinder's vision of Heartland, encompassing not only Russia and Central Asia, but also the Persian Gulf states, parts of Africa and South America.

The narrative of resource wars and the battle for Lebensraum, popularized by Simonov and, especially, Russian fascist philosopher Aleksandr Dugin (2016), soon entered the realm of public policy. In February 2013, Army General Valerii Gerasimov, serving as the chief of the general staff of the Russian armed forces, announced Russia's new military doctrine, stating “for the period up to 2030, the threat of a major war may increase significantly”, for the leading world powers would fight “for fuel and energy resources, markets for goods, and living space” (Felgenhauer, 2018; emphasis added). Similarly, the last pre-invasion edition of the magnum opus on “challenges and threats to Russian national security” edited by Major-General Korzhevskii (2021:213, 435), deputy head of the general staff's Military Academy, debates the conundrum of nature being simultaneously a “warehouse of resources” to be conserved, an expanding “waste dump” of human habitat and zhiznennoe prostranstvo (Lebensraum in Russian) currently suffering from “overpopulation”.

6.2 Borderless Russia: a geography lesson from Vladimir Putin

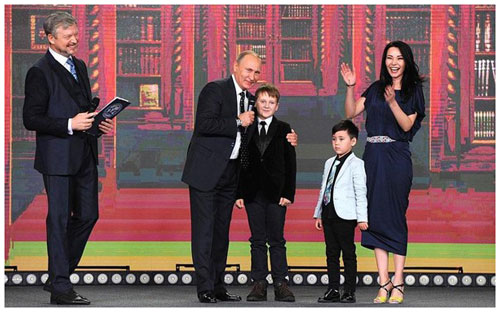

The imperialist outlook of Surkov, as expressed in writing, though not in practice, is purposefully indefinite in terms of its colonial gaze. Vladimir Putin, who has employed Surkov since 1999, has shared this perspective, to an extent (Suslov, 2018). During an award-giving ceremony at the Russian Geographical Society (RGS) in 2016, Putin – as chairperson of the RGS board of trustees – spoke briefly with two geography wonderkids. Having first quizzed Timofei Tsoi, aged 5, about the capital of Burkina Faso, Putin turned to Miroslav Oskirko, aged 9, whom the RGS public relations team dubbed “the boy with satellite vision” for his ability to recognize any country in the world or any Russian region by its outlines on the map. “Where do the borders of Russia end?”, asked Putin. “The borders of Russia end through the Bering Strait with the United States and …”, Miroslav began to answer. Putin interrupted him, proclaiming “Russia's borders end nowhere!” (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1“Russia's borders end nowhere!”: Vladimir Putin grins mischievously, when answering his own question “Where do the borders of Russia end?” amongst the giggling participants of the Russian Geographical Society's awards. The Moscow Kremlin, 24 November 2016. Source: Russia's Presidential Executive Office (CC BY 4.0).

Just 2 years previously, the Russian Geographical Society (RGS), founded in 1845 by Emperor Nicholas I to map his expanding tsardom, made the headlines for similar border-trespassing reasons. Following the Russian occupation of the Crimean peninsula and its annexation in March 2014, the RGS dispatched a geographical expedition to survey the newly acquired territory, including the Crimean coast and the shelf zone (RGS, 2014a; Suslov, 2014). The RGS-sponsored maps of the “Unknown Crimea” were exhibited at the RGS headquarters in St. Petersburg in December 2014 (RGS, 2014b), with a special report delivered to and commented upon by the chairperson of the RGS board of trustees – President Putin. “Being a discoverer” himself, Putin noted “Crimea's shoreline is about 750 kilometres long” (RGS, 2014c).

The role of geography, geographers and their learned societies as enthusiastic collaborators in imperial conquest through centuries is, of course, well documented (Johnston and Sidaway, 2016; Driver, 2000). Indeed, one historiographic account of geography even called it the science of imperialism par excellence (Livingstone, 1993). Admittedly, David Livingstone (1993:220) has warned us against perceiving geography “just as the scientific underwriter of overseas exploitation”. Yet, since the Russian 2008 invasion of Georgia, if not earlier, the RGS ceased to function as an independent learned society and professional body for geography in Russia, being turned into another organ of the state, with Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu becoming the society's president and President Putin acquiring the post of its chairperson (RGS, 2014a, b). Soon, the composition of the RGS board of trustees became a mixture of the Forbes' list of Russian billionaires and its most powerful people list. With such a level of sponsorship, the RGS annual award ceremonies have subsequently developed into lavish, grand affairs (see Fig. 2). At the time of writing, 37 out of 40 RGS trustees were subject to various international personal sanctions (see Supplement).

Figure 2The crystal globe gazing: president of the RGS Sergei Shoigu (left), chairperson of the RGS board of trustees Vladimir Putin (center), and general director of the Moscow Kremlin Museum Yelena Gagarina (right) at the RGS awards ceremony in the Moscow Kremlin, 24 November 2016. Source: Russian Presidential Executive Office (CC BY 4.0).

Putin's forays into geography were soon followed by history. In 2020, he authored an 87-page-long pamphlet about World War II, blaming the UK, the US and Poland (!) for provoking it. The following year, Putin (2021) returned to the issue of Russia's never-ending border in a 7000-word-long pamphlet On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians. In it, the Russian cartographer-in-chief reiterated the old tsardom tales of the “original 12th century meaning” of Ukraine as okraina or periphery and accused the Bolshevik communist leader Lenin of creating modern Ukraine on the lands of historical Russia: “One fact is crystal clear: Russia was robbed, indeed”. To remedy such a gross historical injustice, in Putin's words, Ukraine – suffering under the yoke of a “Nazi regime” – should be reunified, “for we are one people”. After the publication, the essay was distributed across the armed forces of the Russian Federation during the summer of 2021.

6.3 From fiction to real life: the Russian imperialism-cum-colonialism in action

Historically, Russian tsars were never squeamish about describing their colonial campaigns across the vast Eurasian landmass simply as pokorenie (subjugation) of Siberia and the Caucasus and zavoievatel'nye pokhody (conquests) in Central Asia. By contrast, the Kremlin rulers of today and yesterday would never frame their imperial ambitions explicitly as colonization. Yet, as Bouzarovski argues, the Soviet colonial legacy continues to play a vital part in post-Soviet practices of territorial domination and exploitation. Indeed, since 2014, this legacy has been unfolding through the re-colonization of southern and eastern Ukraine via a twin process of forced displacement of the Ukrainian population from the Russian-occupied areas and settlement of those areas by Russian in-migrants. Whilst the number of Ukraine's internally displaced people reached 1.8 million between 2014 and 2022, effectively halving the population of its easternmost war-ravaged provinces, during the same time, the population of the Russian-occupied city of Sevastopol alone increased by 161 920 residents or 42 % (Mykhnenko et al., 2022). No reliable migration data exist in relation to the non-government-controlled areas of eastern Ukraine, which were not formally annexed by Russia before 2022. First-hand witness accounts collected by the author over the years point to a much smaller-scale operation, primarily involving the families of Russian officers stationed in the area and settlers from the neighboring Russian provinces like Rostov-on-Don.

As a clear example of the colonial nature of the 2022 Russian invasion into Ukraine, on 5 March, Ukrainian military-intelligence-related sources published a 1000-word, five-page-long document entitled The Action Plan to Create a System of Control over Economic and Political Processes in Ukraine. The author's copy of the Action Plan was obtained independently and directly from his verified source in one of Ukraine's national security agencies. The document consists of an annotated list of a host of measures to be taken during the Russian colonization of Ukraine, starting with taking over its (1) banking; (2) transport; (3) energy sector; (4) wholesale and retail trade; (5) “denazification” of education and the official status of Russian as the second state language; (6) the insertion of Ukraine into the Russian-dominated Eurasian Economic Union; (7) fiscal affairs, including the printing of money to cover public expenditure and “demilitarization” austerity, including the defunding of the Ukrainian armed forces, national security apparatus, foreign ministry and diplomatic missions abroad; (8) political and legal measures, including the dissolution of the Verkhovna Rada (parliament), government, high courts and all sub-national public administrations up to the municipal level; (9) take-over and confiscation of assets of Russia-hostile owners of all the strategic industries; and (10) the creation of various puppet state organs, kangaroo courts for Russia-hostile elements, and the gradual partition and dismemberment of rump Ukraine through false referendums and/or simple majority votes by “legitimate” local governments (see Supplement).

6.4 Russian imperialism sans frontières: the Kremlin's entropy production for export

Stefan Bouzarovski has urged the geographical community to start paying serious attention to the overlapping colonial and post-colonial socio-technical and geopolitical realities in the Global East, for they are enduring and continue to be socially reproduced. As of the time of writing, the outcome of the Kremlin's entropy production for export into its Ukrainians colonies, both imagined and real, has generated so far between 330 000 and 500 000 casualties, with about USD 1 trillion of material and economic losses. On 11 March 2023, Russia controlled 18.1 % of Ukraine's land mass, in its internationally recognized borders, with 7.3 % being occupied and illegally annexed since 2014 and the rest being captured since the large-scale invasion. During this period, the thermodynamics of Russian imperialism has released enough internal tension to eject around 1 million Russians fleeing mobilization overseas and over 7 million Ukrainians fleeing the Russian invasion westwards.

Further research is needed to provide a theoretically informed account of explanations for the most recent expansion of Russian control, fully recognizing that imperialism is typically a matter of accident as well as design (Jones and Phillips, 2005). So far, the Russian example under investigation here has illustrated the complex and, at times, contradictory inner workings of the phenomenon fairly well. On the one hand, unlike the old “civilizing” Western imperialism of the 19th century, purportedly bringing order and organization into “backward” and “chaotic” lands overseas, today's Russian imperialism is aimed conceptually at expelling its own chaos and disorder outwards, thus fixing the regime's internal contradictions in the process. At the same time, as witnessed during the 2022–2023 military campaign, both Moscow's invasion plans and its colonial practices have involved a great deal of disciplining and punishing of the recently conquered Ukrainian subjects. If Ukrainians prior to the invasion were not portrayed by the Kremlin as the racial “other” but “the same people”, it is highly plausible that over the medium to long run, Russia's colonial role over newly occupied parts of Ukraine – if realized – would echo the earlier Western colonial model of othering, subjugation and dehumanization.