the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Suspended in time? Peripheralised and “left behind” places in Germany

Tim Leibert

The term “left behind” has regained attention with the increasing signs of political dissatisfaction in the Global North, e.g. the rise of right-wing populist parties and politicians. In Germany, terms such as abgehängte Regionen (suspended regions) or “structurally weak” regions are often employed as alternatives. However, there is a certain fuzziness in these terminologies, as they often encompass different spatial scales and temporal dependencies and refer to a variety of regions, e.g. deindustrialising cities as well as peripheral and remote rural areas. Our approach conceptualises “left-behindness” as an outcome of peripheralisation. This allows for a theory-based selection of social, economic, and infrastructural indicators to operationalise left-behindness in Germany at the NUTS3 (nomenclature of territorial units for statistics) level with combining a factor analysis and a k-means cluster analysis. The former resulted in four dimensions of left-behindness with distinct spatial patterns, leading to the classification of six regional types, characterised by varying scores for the four dimensions.

- Article

(4142 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(432 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

The notion of “left behind places” regained traction in discussions about disadvantaged regions regarding social, demographic, cultural, and economic dimensions (Fiorentino et al., 2024). The rapid transformation of the East German socialist planned economy to a market economy and the transfer of the decentralised and democratic political and institutional system of West Germany in the early 1990s caused profound social and spatial disruptions (Enenkel and Rösel, 2022; Röhl, 2018). This resulted in large investments and policies designed to facilitate the modernisation of infrastructure and the equalisation of living standards. However, the public and private sectors were treated inconsistently, overlooking spatial wage differentials (Enenkel and Rösel, 2022). As a consequence an unequal spatial-economic development emerged in the east, characterised by the centralisation of the public sector in larger cities, while manufacturing prioritised small- and medium-sized towns (Enenkel and Rösel, 2022; Hüther et al., 2019). These developments were accompanied by significant selective migration flows towards the west (Enenkel and Rösel, 2022; Leibert, 2016, 2020), resulting in a high degree of spatial polarisation (Dvořák and Zouhar, 2023). The legacy of a divided Germany with two distinct political and economic systems is still evident today. Nevertheless, the disparity is narrowing as a consequence of the expansion of eastern German cities, including Berlin, Leipzig, and Jena (Gohla and Hennicke, 2023). Nevertheless, the majority of regions in southern Germany continue to outperform those in rural eastern Germany, as well as the older industrial regions in the north and west.

To describe and analyse the regions negatively affected by the aforementioned spatial disruptions, the metaphor abgehängte Regionen (literally: “suspended regions”) has been coined by both media and academia (Oberst et al., 2019; Milbert and Demmer, 2017; Diekman and Grigat, 2019). The term is frequently employed to elucidate the electoral triumphs of the populist right-wing party “Alternative for Germany” (AfD) in the 2017 federal election (Deppisch, 2021; Fink et al., 2019), entering the federal parliament with 12.6 % of the votes – an 8 percentage point increase compared to the 2013 elections. Furthermore, the term abgehängte Regionen is frequently used in conjunction with the international concept of “left behind places” (Pike et al., 2023; Röhl, 2018), which has become the “leitmotif of regional inequalities” since the 2008 financial crisis (Pike et al., 2023:1), as well as an explanation of expressions of political discontent (Ejrnæs et al., 2024; Furlong, 2019; Rodríguez-Pose, 2018). The notion originated in an Anglo-American context (Pike et al., 2023) and is frequently employed to describe former industrial regions1. Tomaney et al. (2019) characterise left behind places with an above-average proportion of jobs in industry, a lack of white-collar and graduate-level employment, below-average pay and employment rates, a greater reliance on in-work and especially incapacity benefits, and ageing populations. Martin et al. (2018) and Rodríguez-Pose (2018), on the other hand, focus on deindustrialisation and political discontent.

Similar debates in continental Europe frequently adopt a more rural perspective, focusing on topics such as profound demographic change, inadequate service provision and urban amenities, digital disconnection, and political disengagement (Proietti et al., 2022). In France, the debate focuses on the growing divide between booming metropolises and declining rural areas and medium-sized cities (Fink et al., 2020; Fourquet, 2019; Guilluy, 2014). In Italy, Portugal, and Spain, the focus is on inequalities in socio-economic conditions and infrastructure, especially on the accessibility of mobility, education, and health (Vendemmia et al., 2021; Proietti et al., 2022). A comparable debate on depopulation and the withdrawal of the state and market in rural Latvia is based on the concept of “emptiness” (Dzenovska, 2020), while Dvořák and Zouhar (2023) employ peripheralisation to examine the geography of populist voting in the Czech Republic.

This paper uses the framework of peripheralisation to examine the empirical understanding of left-behindness. This framework views the relationship between core areas and peripheries as a dynamic process that changes over time. This approach integrates economic, demographic, social, and infrastructural dimensions to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors that shape regional development (Kühn and Weck, 2013; Bernt and Liebmann, 2013). We, therefore, posit that left behind places may be a potential outcome of peripheralisation. This interpretation leads to the development of a framework for operationalising the concept of left-behindness, building on a theory-based selection of indicators and linking debates on unequal development of living conditions (e.g. Weingarten and Steinführer, 2020) to the international (academic) literature. Our methodology, a factor analysis followed by a k-means clustering at the district level (NUTS32), enables us to comprehend the underlying dimensions of left-behindness and peripheralisation and to analytically capture the diversity of left behind places that authors such as Oberst et al. (2019), Nilsen et al. (2023), and Velthuis et al. (2023a) have emphasised. A broader range of indicators at a finer scale is employed to provide a more nuanced and multifaceted analysis of left behind places (Tierney et al., 2023). In addition, we consider how different regional or local combinations of indicators can lead to different “varieties of `left-behindness”' (Velthuis et al., 2023a; MacKinnon et al., 2022). The focus on one country enables us to situate the analysis and findings within the specific policy discourses at the national level.

The subsequent sections will address the issue of unequal developments in Germany. This is followed by a theoretical discussion on peripheralisation and left-behindness. In Sect. 3, the data and methodologies employed are described, followed by a presentation and critical discussion of the results and ending with concluding thoughts.

To understand left-behindness and peripheralisation, it is essential to possess a comprehensive understanding of Germany's socio-economic and demographic developments since the reunification in 1990. Since then, the German national economy has experienced an exceptional economic recovery due to the decentralisation of wage bargaining to firm level leading to lower unit labour costs (Dustmann et al., 2018), improved product quality (Marin, 2018), and the opening of the eastern European labour market and its low-cost and skilled labourers (Marin, 2018). Südekum (2018) further posits that the rise of eastern Europe facilitated a more efficacious absorption of the China shock3 and the robotisation of industry compared to the USA. Nevertheless, this economic recovery is a national phenomenon, with different regional outcomes. In particular, regions with large and mainly import-competing manufacturing sectors were struck harder by job losses and lower growth rates despite the expansion of their service sector (Dauth and Südekum, 2016). This resulted in a growing divide between dynamic and disadvantaged regions (Fink et al., 2019)4. The socio-economic consequences of reunification in East Germany included large-scale closures of non-competitive companies, mass unemployment, the disappearance of millions of jobs (especially in industry in the early 1990s), and high out-migration to West Germany (Enenkel and Rösel, 2022). This de-industrialisation was followed by a “de-infrastructuralisation” (Kersten et al., 2019:7) in numerous rural regions. Nevertheless, the resulting east–west disparities narrowed over time due to regional policies, although the gap has not yet been fully closed (Kersten et al., 2019). A comprehensive set of economic policies was implemented under the label Aufbau Ost (literally: “build-up east”), with the objective of privatising the nationally owned enterprises, preparing the East German economy for global competition, rebuilding the infrastructure and encouraging investments (Pohl, 2021; see Blum, 2023, for a detailed analysis of the economic challenges and demographic consequences of these policies). Pohl (2021:19) posits that the Aufbau Ost initiative has achieved its intended objectives whilst leading to the emergence of regional economic disparities. The East Germans' assessment of the economic development since reunification is less positive. A significant proportion of 26 % views it as a failure, while the majority remains undecided regarding the successfulness (Pohl, 2021).

2.1 Regional disparities and regional development policies in Germany

Since the end of World War II, policies of convergence and balancing regional disparities have been in place in (West) Germany with the notion of “equivalent living conditions” as one of the most important socio-political promises of cohesion aiming at reducing disparities between the Länder (German states) and between urban and rural areas (Kersten et al., 2019). Over time, the principles of regional policy in Germany have changed. Equalisation policies were superseded by policies designed to enhance the competitiveness of metropolitan regions (Keim, 2007). These policies promote and encourage centralisation, leading to a concentration of productivity, innovation, and infrastructure in centres. At the same time, they result in a gradual weakening of the development potentials of peripheries in the form of de-differentiation, fragmentation, and contraction (Keim, 2007). Tierney et al. (2023:2–3) contend that market-based regional development policies engender inequalities and that left-behindness represents the “dark side” of such policies. Resulting from these growing disparities, the concept of equivalent living conditions recently regained interest. The federal government's “Plan for Germany” states that “It is a fundamental objective to guarantee equivalent living conditions throughout the entire territory of Germany. For this reason, the resources of the public sector should be allocated in a manner that ensures the provision of equivalent services and development opportunities in all regions” (BMI, 2019a:9). The creation of equivalent living conditions is a cross-cutting task that requires the collaboration and coordinated efforts of different federal ministries, as well as the involvement of the Länder and municipalities (BMI, 2019a). The “Plan for Germany” is largely comprised of “conclusions” and “recommendations” pertaining to various aspects, including the development of structurally weak and rural areas; the generation of employment; and investments in technical and social infrastructure and in networks promoting social engagement, better education, and community building (BMI, 2019a).

The political debate on regional disparities has been criticised as rather unsystematic and not supported by concrete policy (Kersten et al., 2019; Kallert et al., 2021). Firstly, this may be attributable to the limited competencies of the federal government in the field of spatial planning since the constitutional reform of 1994 (Kersten et al., 2019). The responsibility for establishing equivalent living conditions lies with the Länder, which have different priorities and foci (Ragnitz and Thum, 2019). This complicates the way German policies address cross-sectional issues (e.g. regional development), resulting in a situation where regional policy becomes the product of poorly coordinated measures, concepts, and programmes with low overall effectiveness (Keim, 2007). Secondly, there appears to be a contradiction between the reluctance to accept peripheralisation and the expectation that public authorities should “tackle it” (Keim, 2007). A third reason may be that the term equivalent living conditions can be characterised as an “empty signifier” that has never been properly defined and operationalised and hence remains “imprecise and open to different interpretations” (Kallert et al., 2021:330). It is therefore important to carefully measure the consequences of unequal developments, including equivalent living conditions and left-behindness, using indicators supported by theory (Milbert, 2019).

Germany has a long tradition of regional policy (Kersten et al., 2019; Kallert et al., 2021) which contrasts with the unitary systems in countries such as the UK, France, and Italy and the bottom-up approach implemented in the USA (Cox, 2016). One might posit that the objective of spatially balanced economic development has become more salient in the Global North in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, resulting in new spatial policies pertaining to the interaction of three processes: neoliberalism, the rise of state capitalism, and the emergence of populism and discontent in certain regions (MacKinnon et al., 2023). MacKinnon et al. (2023) identify the emergence of new spatial and industrial policies designed to support left behind places that rejected elements of globalism and neoliberalism while maintaining a focus on growth and competitiveness. Notable examples of such policies include the UK's “levelling up” strategy, which is also motivated by the Conservative government's objective of maintaining support for the party in former Labour strongholds in Northern England (Hudson, 2022) and President Joe Biden's Inflation Reduction Act in the USA (MacKinnon et al., 2023).

Left-behindness is approached as both a cause and consequence of unequal living conditions starting from “peripheralisation”, which helps to frame it in the relational and agency-sensitive understanding of spatially uneven development (Lang, 2015). Peripheralisation focusses on the formation of (socio-economic and/or political) peripheries (Bernt and Liebmann, 2013). The concept of “periphery” is inherently vague (Pugh and Dubois, 2021). However, it refers to a state and is often described as a specific locality characterised by a lack of resources and remoteness, while peripheralisation focusses on centre–periphery relations. By referring to processes and actions, it emphasises the distribution of resources. The focus is on the multifaceted nature of relations between actors and places (Bernt and Liebmann, 2013). Hence, this theory permits the inclusion of not only physical peripheries but also places that lost social or economic importance in relation to other places. Peripheralisation can be defined as a “gradual weakening and/or decoupling of the socio-spatial development in a given region vis-à-vis the dominant process of centralisation” (Keim, 2006:3). Peripheries are thus not simply geographical entities but rather (re-)produced through the actions of actors (Kühn and Weck, 2013). The interplay of peripheralisation and centralisation results in socio-spatial polarisation (Barlösius and Neu, 2007). One example of this link between inequality and the multi-dimensional nature of peripheralisation is austerity management at local levels where struggling municipalities are forced by state governments to increase local taxes and cut services in order to reduce debts. This results in reduced competitiveness with their less-left-behind neighbours and a deterioration in the quality of life for the local population (Dudek, 2021).

In the Introduction, we briefly discussed the various interpretations of the term left-behindness. We now turn to the more international definition proposed by Velthuis et al. (2023b:03). Their understanding of left-behindness is a multifaceted phenomenon that affects a diverse array of places, ranging from deindustrialised cities to more peripheral and rural regions. It describes places negatively affected by austerity, globalisation, and technological change (Pike et al., 2023; Velthuis et al., 2023b). It is often used as a shorthand for places experiencing decline or stagnation on economic, demographic, and social development, relative to more dynamic and prosperous places (Velthuis et al., 2023b). However, the variegated nature of left-behindness results in local combinations of disadvantage that may not encompass all indicators (MacKinnon et al., 2022). In Germany, the debate revolves around the highly loaded term abgehängte Regionen and is situated within the context of academic and policy discussions on structurally weak regions and ensuring equivalent living conditions (Oberst et al., 2019; Milbert, 2019; BMI, 2019b). The term is frequently used to describe rural areas with demographic and economic weaknesses and restricted access to services of general interest (SGI), as well as lower voter participation and electoral preferences for right-wing and populist parties (Deppisch, 2021; Weingarten and Steinführer, 2020; Sixtus et al., 2019; Röhl, 2018; Milbert and Demmer, 2017). The topic frequently encompasses a psychological element that evokes sentiments of left-behindness pertaining to the region's economic situation, infrastructure, and cultural matters (Deppisch, 2021). Alternatively, it may encompass a collective regional embitterment that has accumulated over an extended period (Hanneman et al., 2023).

The connection between the discourse on left-behindness and peripheralisation becomes evident when examining the four interrelated, overlapping, and mutually reinforcing dimensions of the process of peripheralisation (Kühn and Weck, 2013; Bernt and Liebmann, 2013). The term left-behindness describes the current state of regions affected by socio-economic decline and political neglect. The concept of peripheralisation provides a more nuanced understanding of why regions became left behind, including the decisions and processes that keep them in this state and the trajectories they follow. Peripheralisation can be the result of creeping decline, abrupt disruption, or a relative worsening in comparison to neighbouring regions (Beißwenger and Weck, 2020). The process encompasses the following dimensions: (1) (selective) migration resulting in a regional “brain drain” undermining the potentials of endogenous regional development, (2) disconnection from economic systems and political decision-making, (3) a dependency on decision-making centres and transfer payments and subsidies, and (4) stigmatisation (Kühn and Weck, 2013; Bernt and Liebmann, 2013). This is an important aspect in the consolidation of peripheries and peripheralisation (Leibert and Golinski, 2016). The disconnection and dependency dimensions of peripheralisation are closely connected to left-behindness, which manifests at both regional and individual levels. A withdrawal of the state and the private sector from a region results in a “left behind place” and deprives the inhabitants of economic opportunities, which, in turn, produces “left behind people” (Bernard et al., 2023). A lack of economic opportunities can trigger a downward spiral. Lacking job prospects leads to selective migration, which, in turn, entails ageing and population decline, impoverishment, infrastructural disinvestments by both public and private stakeholders, political marginalisation, and a reduced attractiveness of the locality in question for investors and potential in-migrants, leading to further out-migration and a gradual loss of the “critical mass” of users needed to sustain the remaining SGIs and technical infrastructure (Weber and Fischer, 2010). This downward spiral serves to illustrate the pivotal role of selective migration in the process of peripheralisation, both in the short and long term.

Our methodological approach to left-behindness is based on the combination of factor analysis and k-means cluster analysis. This allows for an understanding of the multi-dimensionality of left-behindness and the diversity of left behind places. The Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR, 2020) employs a comparable methodology to assess “unequal living conditions”, based on a comprehensive review of existing studies on regional disparities (Fink et al., 2019; Oberst et al., 2019; Sixtus et al., 2019; BBSR, 2017).

The analytical concept is based on the first three dimensions of peripheralisation: selective migration, dependence, and disconnection. Due to the subjective nature of stigmatisation and the lack of quantitative data, this is not considered in the analysis. Selective migration indirectly encompasses population decline and ageing. Nevertheless, we are convinced that both aspects should be more prominently featured, given the close relationship between population development and peripheralisation (see e.g. Bernard and Šimon, 2017; Weber and Fischer, 2010). Furthermore, numerous studies have identified correlations between demographic variables, particularly population decline and ageing, and populist voting and discontent (e.g. Dijkstra et al., 2020; Dvořák and Zouhar, 2023). Dependence and disconnection relate to economic and political decisions that influence employment, innovation, and general economic progress. A lack of these factors can be interpreted as economic left-behindness. Furthermore, deindustrialisation and long-term economic decline are both indicative of a disconnection from the economic system. The differing temporal dimensions of these processes in East and West Germany, in conjunction with the absence of pre-1990 data for East Germany, prompted us to concentrate on the potential for economic progress and innovation in recent decades. Furthermore, the disconnection and dependence also tie together with decisions regarding the reduction in service and infrastructure provision, which can lead to feelings of left-behindness regarding the accessibility of infrastructure (Deppisch, 2021). Additionally, we see political disengagement and discontent (Proietti et al., 2022; MacKinnon et al., 2022; Deppisch, 2021; Hannemann et al., 2023) and right-wing voting (Rodríguez-Pose, 2018; Martin et al., 2018; Tomaney et al., 2019) as a reflection of a disconnection from political decision-making centres. Political disengagement is included in the form of voter turnout in federal elections, as it is comparable across the whole country. Right-wing or populist voting exhibits a specific spatial pattern that will skew the analysis towards a strong east–west division. Consequently, we have decided to exclude this as an indicator. Furthermore, it can be argued that deprivation and disadvantage are absent from the peripheralisation framework despite being frequently mentioned in discussions on left-behindness. This is indicative of an individualised disconnection from society and life opportunities. Statistical data on deprivation and disadvantage demonstrate the spatial concentration of “left behind people” rather than identifying left behind places. Therefore, this dimension is incorporated into our analysis. It is anticipated that the combination and regional distribution of these indicators and processes will result in diverse pathways of peripheralisation and multiple types of peripheries (see e.g. Bernard and Šimon, 2017, and Dvořák and Zouhar, 2023, for the Czech Republic). This rationale led to the selection of 25 indicators of left-behindness available at the district level (NUTS3).

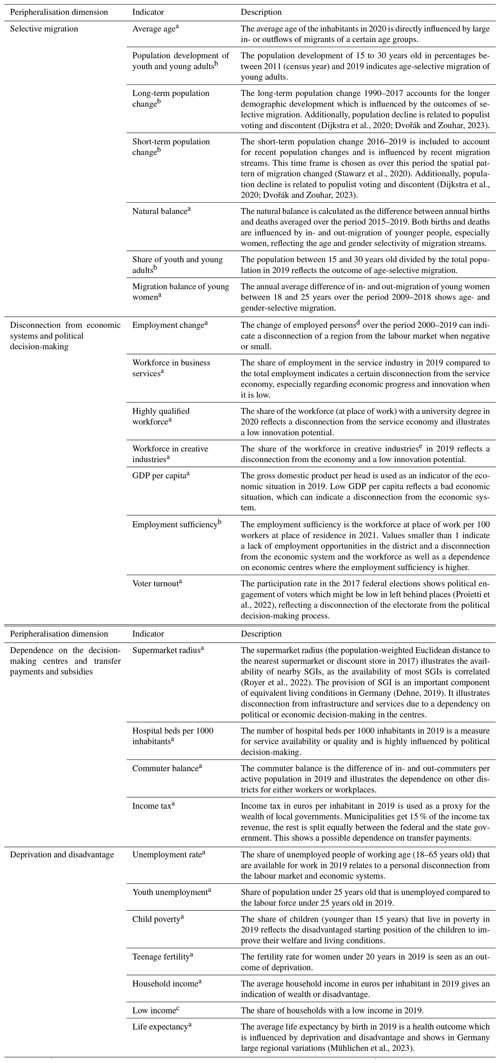

With regard to data availability, the most recent data, which were not affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, were selected. Post-pandemic data (i.e. for 2023) were not available at the time of conducting the analysis. The indicators are described in Table 1 and linked to a dimension of peripheralisation or one of the missing aspects of left-behindness addressed above.

Table 1Description of indicators.

a BBSR (2023). b Source data: Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder (2023), own calculations. c Bertelmann Stiftung (2023). d Employees subject to social insurance contributions, i.e. excluding the self-employed, family workers, and public servants. e Generation or exploitation of knowledge and information.

In a second step, a factor analysis is conducted to reduce the dimensionality of the indicators to a smaller number of underlying dimensions (Bahrenberg et al., 2008) in order to address the complexity and multi-dimensionality of left-behindness. This multivariate approach identifies statistical correlations based on the minimum covariance between different indicators and groups them together, resulting in fewer independent dimensions. This approach facilitates the interpretation of the multi-dimensionality. The analysis was conducted using the statistical software package SPSS (IBM, 2010). The number of factors was determined in accordance with the Kaiser criterion5 (Bahrenberg et al., 2008).

Subsequently, a k-means cluster analysis is employed to elucidate the different factors that combine and constitute varieties of left behind places. The analysis identifies places with similar scores on the different dimensions of left-behindness and groups them together based on their similarity in scores across all factors. The cluster algorithm employed is Lloyd's k-means clustering (Lloyd, 1982). The algorithm determines centroids that minimise the within-cluster sum-of-squares criterion. To address the potential sensitivity of the clustering algorithm to outliers, the Mahalanobis distance6 (Mahalanobis, 1930) is used to identify multivariate outliers7, which are subsequently excluded from the analysis. The optimal number of clusters is identified through the elbow plot method and the gap statistic. The analysis is conducted using the Python module scikit-learn8 (Pedregosa et al., 2011). The resulting typology combines all regions with similar struggles but seemingly different characteristics, thus avoiding the stigmatisation of the worst-performing districts. However, naming the clusters is challenging and can cause stigmatisation (BBSR, 2020).

5.1 Dimensions of left-behindness

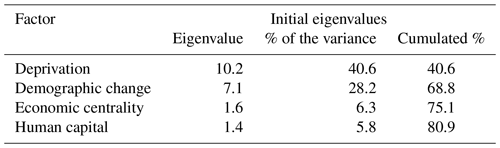

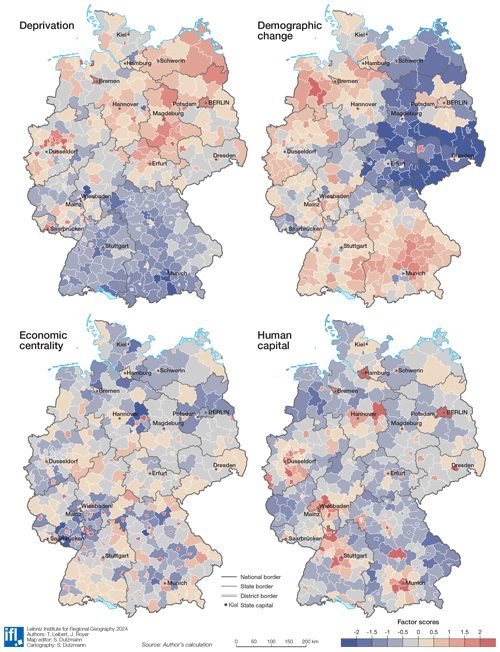

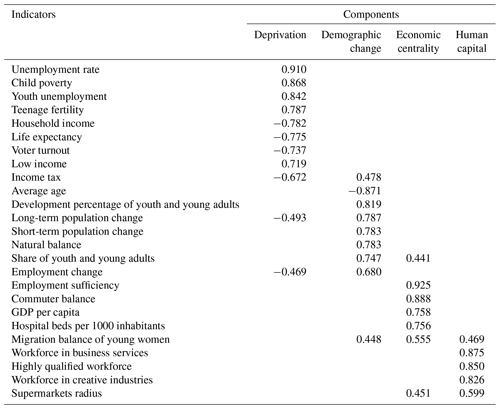

The analysis resulted in four different factors explaining 80.9 % of the variance, which are summarised in Tables 2 and 3 and illustrated in Fig. 1. The first factor explains 40.6 % of the variance. It is influenced by the unemployment rate, child poverty, youth unemployment, teenage fertility, and low incomes and inversely by household income, life expectancy, voter turnout, and income tax. Additionally, it is to a lesser extent inversely influenced by long-term population change and employment change. Since many of those indicators are included in the analysis to give an indication of limited life opportunities and disadvantage, this factor is named “deprivation”. Districts in southern Germany are characterised by lower deprivation rates than in the north. Areas affected by high deprivation include old-industrialised regions, e.g. the Ruhr area and Saarland, as well as sparsely populated rural areas in the northeast and the city states of Bremen and Berlin.

The second factor explains 28.2 % of the variance with high positive factor loadings on the population development of youth and young adults, short- and long-term population change, the natural balance, the share of youth and young adults, employment change, and to a lesser extent the migration balance of young women. Most of these variables relate to demographic change and are (indirectly) affected by selective migration and processes of demographic change. This factor shows a rather clear east–west division of Germany except for Berlin and the surrounding districts in Brandenburg. In the west, Upper Franconia, Saarland, Western Palatinate, North Hesse, and adjacent South Lower Saxony are most affected by negative values of the demographic change factor.

The third factor accounts for 6.3 % of the variance and is influenced by the employment sufficiency ratio; the commuter balance; GDP per capita; hospital beds per 1000 inhabitants; and to a lesser extent the migration balance of young women, the accessibility of supermarkets, and the share of youth and young adults. This factor is named “economic centrality” as the majority of the indicators reflect a certain degree of centralisation of economic activities and infrastructure. The spatial distribution of this factor reveals a more pronounced centrality for numerous smaller urban districts (which are more prevalent in the south) and lower values for the surrounding rural districts.

The fourth factor accounts for 5.8 % of the variance. It is primarily influenced by the workforce in business services, a highly qualified workforce, the workforce in creative industries, and to a lesser extent the distance to supermarkets and the migration balance of young women. These indicators are indicative of a higher presence of “human capital”. The spatial pattern indicates that higher factor scores are present in larger conurbations and major cities, including the Rhine–Ruhr and Cologne–Bonn area, the Rhine–Main area, Munich, Berlin, Hamburg, Bremen, Stuttgart, and Dresden. Furthermore, lower scores for this factor can be found in more peripheral areas, such as the east of Lower Bavaria, the Eifel, and the Weser-Ems region.

5.2 Typology of left behind places

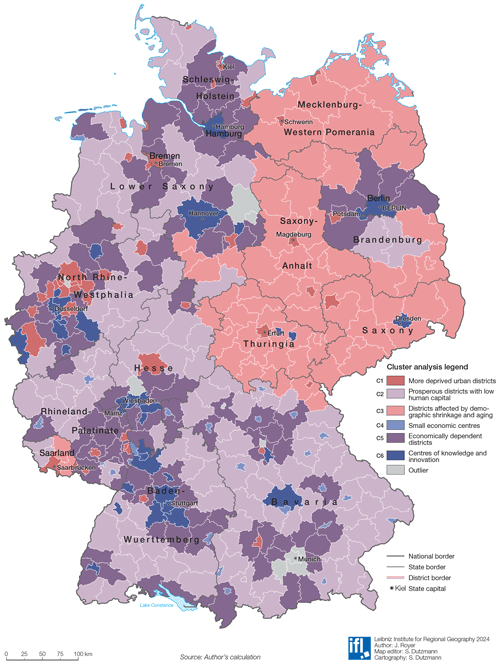

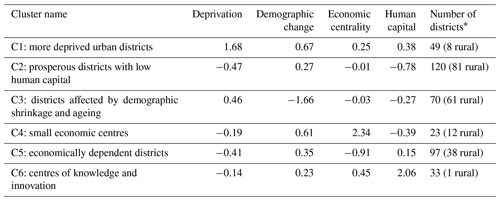

In order to gain a better understanding of how these four different dimensions coincide spatially, a k-means cluster analysis was carried out. This resulted in six clusters. The average values of each cluster for the left behind dimensions, their share of the national population, and the share of rural districts per cluster are given in Table 4, while their geographies are mapped in Fig. 2.

Table 4Average values of each left behind dimension by cluster (without outliers).

* Number of rural districts as defined by BBSR (2018).

The first cluster “C1: more deprived urban districts” is characterised by slightly higher levels of human capital, pronounced deprivation, a favourable demographic trajectory, and a certain degree of economic centrality. This cluster encompasses 49 districts, including cities with sizable student populations and older industrial cities undergoing structural change. The majority of districts in this cluster are situated in the northwest, e.g. Bremen, Bielefeld, and cities in the Ruhr area. The cluster also includes cities in Rhineland-Palatinate, the regional district of Saarbrücken, and most of the eastern German cities. According to a discriminant analysis of the outliers, Gelsenkirchen could be assigned to this cluster because of extremely high deprivation scores.

The characteristics of the second cluster “C2: prosperous districts with low human capital” have low human capital, little deprivation, a rather positive demographic development, and limited dependence on economic centres. This is the largest group, containing 120 districts, accounting for 24.5 % of the German population. They are in a relatively favourable socio-economic situation. Most of these districts are rural and located in the west of Germany.

Cluster “C3: districts affected by demographic shrinkage and ageing” contains 70 districts that are characterised by a very unfavourable demographic situation combined with deprivation and very low human capital. These districts are predominantly rural and mostly located in eastern Germany, along the former intra-German border, and in Saarland.

The 23 districts in cluster “C4: small economic centres” have a high economic centrality, combined with a positive demographic development, low deprivation, but also low human capital. These are mostly smaller urban districts located in the south of Germany, representing 2.5 % of the German population. The outliers Schweinfurt (city) and Wolfsburg would be assigned to this category by a discriminant analysis due to their very high economic centrality.

Cluster “C5: economically dependent districts” is more of a suburban cluster, characterised by slightly above-average human capital, low deprivation, slightly positive demographic development, and low economic centrality. These 97 districts have strong links to central cities and are mostly urbanised rural districts. The districts of this cluster contain 25.8 % of the population; this is the largest share.

The final cluster “C6: centres of knowledge and innovation”, comprises 33 districts characterised by high human capital, relatively low deprivation, positive economic development, and a certain economic centrality. The majority of these districts are large urban centres, such as Berlin, Cologne, Dresden, and Stuttgart, or important centres of higher education, including Heidelberg, Jena, and Münster. The outliers Gifhorn, Hochtaunuskreis, Munich (city and district), and Starnberg are assigned to this cluster based on their high scores on the human capital dimension. Erlangen is included due to its combination of high economic centrality and high human capital.

Several authors (e.g. Velthuis et al., 2023a; Proietti et al., 2022; Milbert, 2019; Oberst et al., 2019; Fink et al., 2019) analysed unequal regional developments with different scales, time frames, and methodologies. Our analysis focuses on the national context of Germany, which allows for an understanding of national policy discourses, outcomes, and history, as well as for the consideration of data availability. Moreover, as Milbert (2019) has observed, a significant proportion of similar studies lack a theoretical framework as a starting point. This contrasts with our approach, which employs the concept of peripheralisation as a causal process of left-behindness and thus integrates it into the relational and agency-sensitive understanding of spatially uneven development (Lang, 2015).

The factor analysis resulted in four dimensions of left-behindness: “deprivation”, “demographic change”, “economic centrality”, and “human capital” with a distinct composition and spatial pattern. These dimensions stress the significance of the debate on left behind places as both places with high concentrations of “left behind people” and places that are left behind due to poor transport infrastructure or low economic dynamism. Deprivation is a more individual-level phenomenon, indicating where individuals are left behind. In contrast, demographic change, economic centrality, and human capital are structural aspects of regions, illustrating where regions are left behind by people, politics, and the economy. The dimensions highlight both central and centralising places, as well as those undergoing peripheralisation or “places becoming left behind”.

There are strong parallels with the dimensions of peripheralisation and the aforementioned factors. Firstly, the factor “deprivation” resonates with deprivation and disadvantage, which was included based on a review of the literature. The spatial pattern demonstrates elevated factor values in northern and eastern Germany and diminished values in the south. It was argued that this dimension fits into the framework as it relates to an individualised disconnection from society and life opportunities. Furthermore, other authors connected poverty with feelings of economic left-behindness (Deppisch, 2021) and political discontent (Rodríguez-Pose, 2018). Secondly, the factor “demographic change” is associated with the indicators of selective migration. However, these indicators relate more generally to demographic change rather than selective migration, hence, the renaming. Furthermore, both ageing (Dijkstra et al., 2020) and demographic decline (Dvořák and Zouhar, 2023) are linked to discontent and a sense of being left behind. The other dimensions of left-behindness – “economic centrality” and “human capital” – combine indicators of disconnection and dependency. This is partly attributable to the interconnection between certain indicators of dependency and disconnection. For instance, decisions regarding investments or reductions in service infrastructure or employment are typically made in economic and political decision-making centres. In the event of financial cutbacks, this can result in the closure of businesses in less-profitable areas, leading to a greater reliance on central locations for the provision of SGI and employment opportunities. This can also result in a sense of disconnection from political decision-making, which may give rise to feelings of left-behindness due to deficiencies in infrastructure and/or lacking economic opportunities (Deppisch, 2021). Furthermore, the concentration of human capital observed in large cities and metropolitan areas, characterised by above-average service sector employment and innovation, is in contrast to low values in remote and rural districts. This dichotomy between more progressive and innovative metropolitan areas and more conservative and traditional rural regions may give rise to feelings of cultural left-behindness (Deppisch, 2021).

Two of the clusters identified through the k-means clustering align with the discussion of left behind places: C1 “more deprived urban districts” and C3 “regions affected by demographic shrinkage and ageing”. Both illustrate that the challenges faced in these districts are connected to more general trends, such as the concentration of poverty in urban areas or ageing and selective migration in rural areas (Fink et al., 2019; Proietti et al., 2022). Many C1 districts are classified by other researchers into similar categories, including “Economic decline and deindustrialisation” (Velthuis et al., 2023a), “Predominantly urban areas with ongoing structural change” (Fink et al., 2019), and “large cities with problems” (Sixtus et al., 2019), aligning well with the Anglo-American discourse. Indicators of deprivation, such as unemployment, youth unemployment, and negative employment change, reflect (personal) disconnection from the economic system. Furthermore, a negative relation with voter turnout shows there is a disconnection between the electorate and the political system. Both link deprivation with peripheralisation. Some C1 districts are characterised by structural change and difficulties in adapting to the shift towards a service-oriented economy. Despite the general increase in service jobs in Germany, the loss of manufacturing jobs in these districts was not offset by gains in other sectors, resulting in higher unemployment rates among young people (Dauth and Südekum, 2016). This, in turn, contributes to the high deprivation scores observed in these districts. These districts have experienced a loss of importance in comparison to the national (or even international) economic system, becoming more peripheral as a result. This is also reflected in the lower economic centrality of these districts in comparison to the other central districts. Nevertheless, the presence of higher education and research institutions can result in differential outcomes of peripheralisation (Butzin and Flögel, 2024). Such locations frequently exhibit a positive demographic development, as they tend to attract younger individuals seeking education or work experience. This is reflected in the slightly higher human capital, which in turn leads to a certain economic centrality. Additionally, many students with limited or no individual income are registered at their place of study, which skews income statistics and gives the impression of greater deprivation in dynamic cities with a youthful population, despite the support of their parents. This “informal” support is not included in official income statistics, leading to financial challenges due to reduced tax incomes. In other studies, some districts are classified as either “Long-term economic prosperity” (Velthuis et al., 2023a) or “Dynamic large and medium-sized towns/cities with risk of exclusion” (Fink et al., 2019), e.g. Leipzig, Flensburg, and Kiel.

C3 is comprised primarily of rural districts adversely affected by selective out-migration, resulting in an ageing population. This is consistent with the continental European understanding of left-behindness. The factor scores on the four dimensions of left-behindness illustrate the outcomes of peripheralisation. The ageing population; the emigration of young adults, in particular young women (Leibert, 2016); and high deprivation present significant challenges to future regional development. A relative (or absolute) decline in both employment and population, resulting in a reduction in tax income, has a negative impact on the financial stability of communities. This, in turn, leads to a vicious circle of reduced possibilities to invest in retaining the population and job creation (Wolff et al., 2021). This illustrates a dependence on transfer payments and subsidies to maintain existing SGI and employment, which might result in feelings of left-behindness or collective embitterment (Dvořák and Zouhar, 2023; Hannemann et al., 2023). The demographic situation and deprivation result from the legacy of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and reunification (Enekel and Rosel, 2022; Fink et al., 2019). Many, but not all, C3 districts are in the former GDR territory, while most of the major East German cities belong to C1 or C6 due to a better demographic situation. Furthermore, the lack of employment opportunities and economic centrality was caused by the collapse of the East German economy in the 1990s, which resulted in mass unemployment. Additionally, policies applied after the reunification focused strongly on industrial production in rural areas, while neglecting innovation in urban areas (Enenkel and Rösel, 2022). Cluster C3 is comparable with categories of other studies, including “Demographic decline and ageing” (Velthuis et al., 2023a) and “Predominantly rural areas in permanent structural crisis” (Fink et al., 2019). The latter focusses strongly on east Germany, with the regions of Saarland and southern Lower Saxony being overlooked. This results in an overemphasis on east–west differences.

The four other clusters do not necessarily qualify as left behind, in particular the clusters C4 “small economic centres” and C6 “centres of knowledge and innovation”. These districts reflect the outcomes of centralisation processes. Notably the spatial pattern of C4 comprises small- or medium-sized towns with high economic centrality and is often surrounded by districts with low economic centrality. The majority of these small- or medium-sized towns are located in Bavaria and Rhineland-Palatinate (Hüther et al., 2019). In other regions of Germany, similar-sized cities are incorporated into the surrounding district, thereby balancing out the respective high and low economic dependency scores. This results in the absence of C4 in northern and eastern Germany. The legacy of medium-sized towns constituting districts in their own right in the south demonstrates how our classification is influenced by the way statistical units are constructed, also known as the modifiable areal unit problem (MAUP) (Openshaw and Taylor, 1981). Consequently, it is of the utmost importance to be critical of these results and to conduct a more in-depth analysis in order to gain a deeper understanding of the underlying local causes before designing policies. Nevertheless, these differences also illustrate the importance of small- and medium-sized towns and cities in regional development. However, the agglomeration effect on the rural surroundings of the C6 cities in eastern Germany (with the exception of Berlin) is less pronounced than in the west.

C2 “prosperous districts with low human capital” and C5 “economically dependent districts” are respectively behind on human capital and economic centrality. However, the majority of these districts are classified by Velthuis et al. (2023a) as either “High growth” or as “Relative economic and demographic stability” or are generalised by Fink et al. (2019) to “Germany's solid middle”. The majority of districts belonging to C2 and C5 are located within commuter belts of C1, C4, or C6, reflecting a high degree of economic dependence. These districts are assumed to be not left behind. It is crucial to recognise that there may be obstacles when economically central districts encounter difficulties in adopting innovation and transitioning to a more future-oriented economy. Nevertheless, a certain degree of dependence may not be inherently problematic, as some of these areas can be seen as positive peripheries (Pugh and Dubois, 2021). Some of the indicators of human capital and economic centrality are workplace-based measures and are concentrated in certain districts, while other areas are innovation or economic peripheries lacking human capital or economic centrality. Especially the districts in cluster C5 demonstrate that this lack of economic dynamism is not necessarily linked to unfavourable social or labour market outcomes. Both C2 and C5 illustrate the influence of commuting, which provides a connection to other economic systems and markets (C1, C4, and C6). This implies that these districts provide labour and human capital to central districts while receiving wealth in return due to commuting or home office. Nonetheless, some C2 and C5 districts are less connected with the economic centres. Their low values for human capital and economic centrality reflect disconnection from the economic and political centres resulting from peripheralisation (Kühn and Weck, 2013).

In conclusion, there is a continuing debate in Germany about the concept of left-behindness, regardless of the federal structure and the strong regional policies. Our findings indicate that both the Anglo-American and the European understandings of left behind places are present in Germany, with deprivation and demographic change as key dimensions. Consequently, we propose that peripheralisation provides a useful framework for analysing the phenomenon of left-behindness, which can be further refined by incorporating indicators of deprivation, leading to the identification of distinct forms of left-behindness. Furthermore, it allows for a framing within international policy and academic debates on regional development.

Furthermore, our findings demonstrate that economic centrality and human capital are crucial elements in the regional typology, leading to a spectrum of districts that may be (or potentially become) left behind depending on their disconnection from economic systems and political decision-making and dependency on decision-making centres and transfer payments and subsidies. The economic dependency and lacking human capital in many suburban and more peripheral districts also highlight the need for further research into the influence of commuting and the potential of home offices on regional development pathways. Furthermore, the results indicate that medium-sized towns can serve as an anchor for regional development. Nevertheless, the centralisation in medium-sized towns can as well lead to losses of central functions in surrounding towns and districts (Kühn and Milstrey, 2015).

Moreover, the concept of peripheralisation is relatively “neutral”, allowing for its application in different national contexts. This provides a solid foundation for international comparisons, as it allows for the selection of appropriate indicators. Additionally, the concept is sufficiently flexible to encompass the possibility of exiting the status of left behind place or periphery, as well as the potential for territories to be affected by one or several of the dimensions to varying degrees. In addition, peripheralisation occurs on different scales and in a variety of places, i.e. not only in (physical) peripheries but also in more central places undergoing structural changes. Furthermore, it is crucial to recognise that not only left behind places but also peripheralising middle-income districts can get stuck in a regional development trap (Diemer et al., 2022) and that “non-left behind places” can be home to significant populations of left behind, i.e. marginalised, people. Failure to address the specific needs of these areas in a timely manner may result in regional embitterment (Hannemann et al., 2023). Especially against the backdrop that the “Plan for Germany” has not been very visible since the change in government. Our analysis indicates that the implementation of nationwide spatial policies could be beneficial in enhancing spatial cohesion within the country and in mitigating discontent and regional embitterment.

The dataset used for this study is available in the Supplement to this article.

The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-79-221-2024-supplement.

Both authors were involved in the production of this research paper. TL was responsible for compiling the data and the factor analysis, while JR carried out the clustering analysis. Both authors jointly developed the concept of the paper and interpreted the results of the analyses. JR wrote the manuscript with the support of TL.

The contact author has declared that neither of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

This paper is an output of the project “Beyond `Left Behind Places': Understanding Demographic and Socio-economic Change in Peripheral Regions in France, Germany and the UK” (grant reference ES/V013696/1), funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), L'Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR), and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). We are grateful to the funders for their support. Furthermore, the authors would like to thank Sanne Velthuis, Mehdi Le Petit-Guerin, and the organisers and participants of the working group “Social and political consequences of spatial inequalities – the rural gap, peripheralisation and left behind rural areas” at the XXIXth European Society for Rural Sociology Congress for their feedback.

The work of the German project team of the 'Beyond Left Behind Places' project has been funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (project no. 440773899).

This paper was edited by Marco Pütz and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Bahrenberg, G., Giese, E., Mevenkamp, N., and Nipper, J.: Statistische Methoden in der Geographie. Band 2: Multivariate Statistik, 3rd edn., Stuttgart, Borntraeger Verlagsbuchhandlung, ISBN 978-3-443-07144-8, 2008.

Barlösius, E. and Neu, C.: “Gleichwertigkeit–Ade?”: Die Demographisierung und Peripherisierung entlegener ländlicher Räume, PROKLA, Zeitschrift für kritische Sozialwissenschaft, 37, 77–92, https://doi.org/10.32387/prokla.v37i146.527, 2007.

BBSR: Regionen mit stark unterdurchschnittlichen Lebensverhältnissen, https://www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/DE/forschung/fachbeitraege/raumentwicklung/2016-2020/abgehaengte-regionen/abgehaengte_regionen.html, (last access: 1 June 2023), 2017.

BBSR: Raumbeobachtung – Laufende Raumbeobachtung – Raumabgrenzungen, Städtischer und Ländlicher Raum, https://www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/DE/forschung/raumbeobachtung/Raumabgrenzungen/deutschland/kreise/staedtischer-laendlicher-raum/kreistypen.html (last access: 26 April 2023), 2018.

BBSR: Regionale Lebensverhältnisse: Ein Messkonzept zur Bewertung ungleicher Lebensverhältnisse in den Teilräumen Deutschlands, BBSR-Online-Publikation 06/2020, Bonn, https://www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/DE/veroeffentlichungen/bbsr-online/2020/bbsr-online-06-2020-dl.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=6Last (last access: 30 April 2024), 2020.

BBSR: INKAR – Indikatoren und Karten zur Raum- und Stadtentwicklung, https://www.inkar.de/, last access: 26 April 2023.

Beißwenger, S., and Weck S.: Raumwissenschaftliche Perspektiven auf Peripherisierungsprozesse im deutschen Kontext, OeZG, 31, 169–189, https://doi.org/10.25365/oezg-2020-31-2-8, 2020.

Bernard, J. and Šimon, M.: Vnitřní periferie v Česku: Multidimenzionalita sociálního vyloučení ve venkovských oblastech, Czech Sociol. Rev., 53, 3–28, https://doi.org/10.13060/00380288.2017.53.1.299, 2017.

Bernard, J., Steinführer, A., Klärner, A., and Keim-Klärner, S.: Regional opportunity structures: A research agenda to link spatial and social inequalities in rural areas, Prog. Hum. Geog., 47, 103–123, https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325221139980, 2023.

Bernt, M. and Liebmann H.: Zwischenbilanz: Ergebnisse und Schlussfolgerungen des Forschungsprojekts, in: Peripherisierung, Stigmatisierung, Abhängigkeit? Deutsche Mittelstädte und ihr Umgang mit Peripherisierungsprozessen, edited by: Bernt, M. and Liebmann H., Wiesbaden: Springer VS., 218–231, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-19130-0, 2013.

Bertelsmann Stiftung: Wegweiser Kommune, https://www.wegweiser-kommune.de, last access: 26 April 2023.

Blum, U.: What Can Ukraine Learn from Aufbau Ost?, Intereconomics: Review of European Economic Policy, 58, 119–126, https://doi.org/10.2478/ie-2023-0023, 2023.

BMI: Unser Plan für Deutschland: Gleichwertige Lebensverhältnisse überall, Berlin, https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/downloads/DE/veroeffentlichungen/themen/heimat-integration/gleichwertige-lebensverhaeltnisse/unser-plan-fuer-deutschland-langversion-kom-gl.html;jsessionid=8A129F0D0A4E40F00958E73C23B0E07A.live881 (last access: 15 April 2024), 2019a.

BMI: Deutschlandatlas: Karten zu gleichwertigen Lebensverhältnissen, Berlin, https://www.deutschlandatlas.bund.de/DE/Home/home_node.html (last access: 10 May 2024), 2019b.

Butzin, A. and Flögel, F.: High-tech development for “left behind” places: lessons-learnt from the Ruhr cybersecurity ecosystem, Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc., 17, 307–322, https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsad041, 2024.

Cox, K. R.: The politics of urban and regional development and the American exception, Syracuse University Press, ISBN 9780815634393, 2016.

Dauth, W. and Südekum J.: Globalization and Local Profiles of Economic Growth and Industrial Change, J. Econ. Geogr., 16, 1007–1034, https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbv028, 2016.

Dehne, P.: Daseinsvorsorge: Schlüssel für gleichwertige Lebensverhältnisse?, in: Die Zukunft der Regionen in Deutschland Zwischen Vielfalt und Gleichwertigkeit, edited by: Hüther, M., Südekum, J., and Voigtländer, M., 67–84, ISBN 978-3-602-45621-5, 2019.

Deppisch, L.: “Where people in the countryside feel left behind populism has a clear path”: an analysis of the popular media discourse on how infrastructure decay, fear of social decline, and right-wing (extremist) values contribute to support for right-wing populism (No. 310729), Johann Heinrich von Thünen-Institut (vTI), Federal Research Institute for Rural Areas, Forestry and Fisheries, https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.310729, 2021.

Diekman, F. and Grigat, G.: Boomendes Deutschland – abgehängtes Deutschland, Der Spiegel, https://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/soziales/deutschland-in-karten-diese-regionen-sind-abgehaengt-und-diese-boomen-a-1283098.html (last access: 25 September 2022), 2019.

Diemer, A., Iammarino, S., Rodríguez-Pose, A., and Storper M.: The regional development trap in Europe, Econ. Geogr., 98, 487–509, https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2022.2080655, 2022.

Dijkstra, L., Poelman, H., and Rodríguez-Pose, A.: The geography of EU discontent, Reg. Stud., 54, 737–753, https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1654603, 2020.

Dudek, S.: Die schleichende Krise strukturschwacher Kommunen: Zur Situation der Grundversorgung in ländlichen Räumen, PROKLA, Zeitschrift für kritische Sozialwissenschaft, 51, 417–433, https://doi.org/10.32387/prokla.v51i204.1957, 2021.

Dustmann, C., Fitzenberger, B., Schönberg, U., and Spitz-Oener, A.: From sick man of Europe to economic superstar: Germany's resurgence and the lessons for Europe, in: Explaining Germany's Exceptional Recovery, edited by: Marin, D., CEPR Press, 21–30, ISBN 978-1-912179-13-8, 2018.

Dvořák, T. and Zouhar, J.: Peripheralization Processes as a Contextual Source of Populist Vote Choices: Evidence from the Czech Republic and Eastern Germany, EEPS, 37, 983–1010, https://doi.org/10.1177/08883254221131590, 2023.

Dzenovska, D.: Emptiness: Capitalism without people in the Latvian countryside, Am. Ethnol., 47, 10–26, https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12867, 2020.

Ejrnæs, A., Dagnis Jensen, M., Schraff, D., and Vasilopoulou, S.: Introduction: Regional Inequality and Political Discontent in Europe, J. Eur. Public Policy, 31, 1–29, https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2024.2333850, 2024.

Enenkel, K. and Rösel F.: German reunification: Lessons from the German approach to closing regional economic divides, Resolution Foundation, https://economy2030.resolutionfoundation.org/reports/german-reunification (last access: 15 April 2024), 2022.

Fiorentino, S., Glasmeier, A. K., Lobao, L., Martin, R., and Tyler, P.: “Left behind places”: what are they and why do they matter?, Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc., 17, 1–6, 2024.

Fink, P., Hennicke, M., and Tiemann H.: Unequal Germany: Socioeconomic Disparities Report, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Bonn, ISBN 978-3-96250-445-8, 2019.

Fink, P., Manz, T., and Paris, F.: An inegalitarian France: Regional socio-economic disparities in France, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Bonn, http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/paris/17929.pdf (last access: 14 October 2023), 2020.

Fourquet, J.: L'archipel français. Naissance d'une nation multiple et divisée, Humanisme, 324, 58–65, https://doi.org/10.3917/HUMA.324.0058, 2019.

Furlong, J.: The changing electoral geography of England and Wales: Varieties of “left-behindedness”, Polit. Geogr., 75, 102061, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.POLGEO.2019.102061, 2019.

Gohla, V. and Hennicke M.: Ungleiches Deutschland Sozioökonomischer Disparitätenbericht, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Bonn, ISBN 978-3-98628-409-1, 2023.

Guilluy, C.: La France périphérique, Editions Flammarion, Paris, ISBN 9782081312579, 2014.

Hannemann, M., Henn, S., and Schäfer, S.: Regions, emotions and left-behindness: a phase model for understanding the emergence of regional embitterment, Reg. Stud., 58, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2023.2218886, 2023.

Hudson, R.: “Levelling up” in post-Brexit United Kingdom: Economic realism or political opportunism?, Local Economy, 37, 50–65, https://doi.org/10.1177/02690942221099480, 2022.

Hüther, M., Südekum, J., and Voigtländer, M.: Die Zukunft der Regionen in Deutschland: Zwischen Vielfalt und Gleichwertigkeit, IW-Studien, Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft Köln Medien GmbH, Köln, ISBN 978-3-602-45621-5, 2019.

IBM Corp: IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 19.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp, https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/spss-statistics/saas?topic=features-factor-analysis (last access: 25 October 2023), 2010.

Kallert, A., Belina, B., Miessner, M., and Naumann, M.: The Cultural Political Economy of rural governance: Regional development in Hesse (Germany), J. Rural Stud., 87, 327–337, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.09.017, 2021.

Keim, K.-D.: Peripherisierung ländlicher Räume: Essay, APuZ 37, 3–7, https://www.bpb.de/shop/zeitschriften/apuz/29544/peripherisierung-laendlicher-raeume-essay (last access: 20 November 2023), 2006.

Keim, K.-D.: Regionalpolitische Antworten auf die Peripherisierung ländlicher Räume, in: Berichte und Abhandlungen 13 De Gruyter Akademie Forschung Berlin, Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 35–42, ISBN 978-3-05-004425-5, 2007.

Kersten, J., Neu, C., and Vogel, B.: Gleichwertige Lebensverhältnisse: Für eine Politik des Zusammenhalts, APuZ, 46, 4–11, 2019.

Kühn, M. and Milstrey, U.: Medium-Sized Cities as Peripheral Centers: Cooperation, Competition and Hierarchy in Shrinking Regions, Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 73, 185–202, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13147-015-0343-x, 2015.

Kühn, M. and Weck, S.: Peripherisierung: ein Erklärungsansatz zur Entstehung von Peripherien, in: Peripherisierung, Stigmatisierung, Abhängigkeit?, edited by: Bernt, M. and Liebmann, H., Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, 24–46, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-19130-0, 2013.

Lang, T.: Socio-economic and political responses to regional polarisation and socio-spatial peripheralisation in Central and Eastern Europe: a research agenda, Hungarian Geographical Bulletin, 64, 171–185, 2015.

Leibert, T.: She leaves, he stays? Sex-selective migration in rural East Germany, J. Rural Stud., 43, 267–279, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.06.004, 2016.

Leibert, T.: Wanderungen und Regionalentwicklung. Ostdeutschland vor der Trendwende?, in: Regionalentwicklung in Ostdeutschland: Dynamiken, Perspektiven und der Beitrag der Humangeographie, edited by: Becker, S. and Naumann, M., 199–210, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-60901-9, 2020.

Leibert, T. and Golinski S.: Peripheralisation: the missing link in dealing with demographic change?, CPoS, 41, 255–284, https://doi.org/10.12765/CPoS-2017-02en, 2016.

Lloyd, S.: Least squares quantization in pcm, IEEE T. Inform. Theory, 28, 129–137. 1982.

MacKinnon, D., Kempton, L., O'Brien, P., Ormerod, E., Pike, A., and Tomaney, J.: Reframing urban and regional “development” for “left behind” places, Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc., 15, 39–56, https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsab034, 2022.

MacKinnon, D., Kinossian, N., Pike, A., Béal, V., Lang, T., Rousseau, M., and Tomaney, J.: Spatial Policy Since the Global Financial Crisis, Beyond Left Behind Places Working Paper Series, Working Paper 05/23, https://research.ncl.ac.uk/beyondleftbehindplaces/publicationsanddownloads/Spatial policy since the global financial crisis_WP version.pdf (last access: 14 May 2024), 2023.

Mahalanobis, P. C.: On tests and measures of group divergence, Journal and Proceedings, 26, 541–588, 1930.

Marin, D.: Global value chains, product quality, and the rise of Eastern Europe, in: Explaining Germany's Exceptional Recovery, edited by: Marin, D., CEPR Press, 41–46, ISBN 978-1-912179-13-8, 2018.

Martin, R., Tyler, P., Storper, M., Evenhuis, E., and Glasmeier, A.: Globalization at a critical conjuncture?, Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc., 11, 3–16, 2018.

Milbert, A.: Wie misst man “Gleichwertige Lebensverhältnisse”?, APuZ: Beilage zur Wochenzeitung Das Parlament, 69, 25–31, 2019.

Milbert, A. and Demmer, S.: Der Nichtwähleranteil ist dort höher, Reihe: Abgehängte Regionen, Deutschlandfunk.de, https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/reihe-abgehaengte-regionen-der-nichtwaehleranteil-ist-dort-100.html (last access: 11 September 2022), 2017.

Mühlichen, M., Lerch, M., Sauerberg, M., and Grigoriev, P.: Different health systems–Different mortality outcomes? Regional disparities in avoidable mortality across German-speaking Europe, 1992–2019, Soc. Sci. Med., 329, 115976, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115976, 2023.

Nilsen, T., Grillitsch, M., and Hauge, A.: Varieties of periphery and local agency in regional development, Reg. Stud., 57, 749–762, 2023.

Oberst, C., Kempermann H., and Schröder, C.: Räumliche Entwicklung in Deutschland, in: Die Zukunft der Regionen in Deutschland Zwischen Vielfalt und Gleichwertigkeit, edited by: Hüther, M., Südekum, J., and Voigtländer, M., 87–114, ISBN 978-3-602-45621-5, 2019.

Openshaw, S. and Taylor, P. J.: The modifiable areal unit problem, in: Quantitative Geography: A British View, edited by: Wringley, N. and Bennett, R., Routledge and Kegan Paul, London, 60–69, ISBN 0710007310, 1981.

Pike, A., Béal, V., Cauchi-Duval, N., Franklin, R., Kinossian, N., Lang, T., Leibert, T., MacKinnon, D., Rousseau, M., Royer, J., and Servillo, L.: “Left behind places”: a geographical etymology, Reg. Stud., 58, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2023.2167972, 2023.

Pedregosa, F., Varoquaux, G., Gramfort, A., Michel, V., Thirion, B., Grisel, O., Blondel, M., Prettenhofer, P., Weiss, R., Dubourg, V., and Vanderplas, J.: Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python, J. Mach. Learn. Res., 12, 2825–2830, 2011.

Pohl, R.: Aufbau Ost: Lief da etwas falsch?, Wirtschaftsdienst, 101 (Suppl. 1), 14–20, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10273-021-2834-4, 2021.

Proietti, P., Sulis, P., Perpiña Castillo, C., Lavalle, C., Aurambout, J. P., Batista e Silva, F., Bosco, C., Fioretti, C., Guzzo, F., Jacobs-Crisioni, C., Kompil, M., Kučas, A., Pertoldi, M., Rainoldi, A., Scipioni, M., Siragusa, A., Tintori, G., and Woolford, J.: New perspectives on territorial disparities: From lonely places to places of opportunities, edited by: Proietti, P., Sulis, P., Perpiña Castillo, C., and Lavalle, C., Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, https://doi.org/10.2760/847996, 2022.

Pugh, R. and Dubois, A.: Peripheries within economic geography: Four “problems” and the road ahead of us, J. Rural Stud., 87, 267–275, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.09.007, 2021.

Ragnitz, J. and Thum, M.: Gleichwertig, nicht gleich: Zur Debatte um die “Gleichwertigkeit der Lebensverhältnisse”, APuZ 46, 13–18, 2019.

Rodríguez-Pose, A.: The revenge of the places that don't matter (and what to do about it), Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc., 11, 189–209, https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx024, 2018.

Röhl, K. H.: Regionale Konvergenz: Der ländliche Raum schlägt sich gut, Wirtschaftsdienst, 98, 433–438, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10273-018-2312-9, 2018.

Royer, J., Velthuis, S., Le Petit-Guerin, M., Franklin, R., Leibert, T., Cauchi-Duval, N., Mackinnon, D., and Pike, A.: Regional travel times to services of general interest in the EU15. Beyond Left Behind Places Project Working Paper 02/22, Newcastle University, UK, Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies (CURDS), https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/c2bvh, 2022.

Sixtus, F., Slupina, M., Sütterlin, S., Amberger, J., and Klingholz, R.: Teilhabeatlas Deutschland: Ungleichwertige Lebensverhältnisse und wie die Menschen sie wahrnehmen, ISBN 978-3-946332-52-7, 2019.

Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder: Regionaldatenbank Deutschland, https://www.regionalstatistik.de/genesis/online/, last access: 26 April 2023.

Stawarz, N., Sander, N., Sulak, H., and Rosenbaum-Feldbrügge, M.: The turnaround in internal migration between East and West Germany over the period 1991 to 2018, Dem. Res., 43, 993–1008, https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2020.43.33, 2020.

Südekum, J.: The China shock and the rise of robots: Why Germany is different, in: Explaining Germany's Exceptional Recovery, edited by: Marin, D., CEPR Press, 47–54, ISBN 978-1-912179-13-8, 2018.

Tierney, J., Weller, S., Barnes, T., and Beer, A.: Left-behind neighbourhoods in old industrial regions, Reg. Stud., 58, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2023.2234942, 2023

Tomaney, J., Pike, A., and Natarajan, L.: Land-use planning, inequality and the problem of “left-behind places”: A “provocation” for the UK, 2070 Commission-An Inquiry into Regional Inequalities Towards a Framework for Action, https://uk2070.org.uk/2019/02/26/collaborative-think-piece-by-ucl-and-newcastle-universities-on (last access: 17 October 2023), 2019.

Velthuis, S., Royer, J., Le Petit-Guerin, M., Cauchi-Duval, N., Franklin, R., Leibert, T., MacKinnon, D., and Pike, A.: Locating “left-behindness” in the EU15: a regional typology. Beyond Left Behind Places Project Working Paper 03/23, Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies (CURDS), Newcastle University, UK, https://research.ncl.ac.uk/beyondleftbehindplaces/publicationsanddownloads (last access: 10 May 2024), 2023a.

Velthuis, S., Le Petit-Guerin, M., Royer, J., Franklin, R., Leibert, T., Cauchi-Duval, N., Mackinnon, D., and Pike, A.: The characteristics and trajectories of “left behind places” in the EU15. Beyond Left Behind Places Project Policy Briefing #1, 02/23, Newcastle University, UK: Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies (CURDS), https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/t96fa, 2023b.

Vendemmia, B., Pucci, P., and Beria, P.: An institutional periphery in discussion. Rethinking the inner areas in Italy, Appl. Geogr., 135, 102537, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2021.102537, 2021.

Weber, G. and Fischer, T.: Gehen oder Bleiben: Die Motive des Wanderungs- und Bleibeverhaltens junger Frauen im ländlichen Raum der Steiermark, Studie im Auftrag des Amtes der Steiermärkischen Landesregierung durchgeführt am Institut für Raumplanung und Ländliche Neuordnung, Universität für Bodenkultur Wien, Graz, https://ams-forschungsnetzwerk.at/downloadpub/BOKU_endbericht_gehen_bleiben_03_10.pdf (last access; 20 October 2023), 2010.

Weingarten, P. and Steinführer, A.: Daseinsvorsorge, gleichwertige Lebensverhältnisse und ländliche Räume im 21. Jahrhundert, ZPol, 30, 653–665, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41358-020-00246-z, 2020.

Wolff, M., Haase, A., and Leibert, T.: Contextualizing small towns–trends of demographic spatial development in Germany 1961–2018, Geogr. Ann. B, 103, 196–217, https://doi.org/10.1080/04353684.2021.1884498, 2021.

However, especially in the USA, peripheral and rural places are also mentioned in the discussions (Rodríguez-Pose et al., 2021).

Nomenclature of territorial units for statistics 2016.

Accession of China in the WTO in 2001.

Weingarten and Steinführer (2020:656) argue that claims that German regions are drifting apart and that especially rural areas are being decoupled from societal development are not supported by statistical data.

The Kaiser criterion sets the threshold for the eigenvalue at 1, and all factors which comply are retained.

The Mahalanobis distance is a multivariate distance metric for measuring the distance between a point and a distribution. This measure is often used for multivariate outlier analysis.

Wolfsburg, Gifhorn, Gelsenkirchen, Hochtaunuskreis, Munich (city), Munich (district), Starnberg, Erlangen, and Schweinfurt (city).

Open-source software for machine learning.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Unequal developments in Germany

- Peripheralisation as theoretical framework to understand left-behindness

- Data and methods

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusions

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement

left behind, Abgehängte (suspended), and

structurally weakhave gained popularity to describe regions with increased support for right-wing populist parties in Germany and elsewhere. These concepts are not clearly defined. We give meaning to

left behind placesin Germany both by identifying the dimensions and varieties of

left-behindnessand by framing it as an outcome of peripheralisation processes.

left behind, Abgehängte (suspended), and

structurally weakhave gained popularity to...

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Unequal developments in Germany

- Peripheralisation as theoretical framework to understand left-behindness

- Data and methods

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusions

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement