the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Shifting values at the cemetery – the artistic interventions of DeathLab

Mathias Siedhoff

Jeannine Wintzer

Cemeteries are a reflection of the values, history, and composition of their respective communities. Current social developments are therefore also visible through them. The contribution describes the work of DeathLab, a public event series that uses contemporary artist-designed urns as a means of exploring shifting values in funeral culture through physical manifestations. The events involve visits to places associated with farewells and allow for discussions about the cultural significance of death and mourning practices. The practices surrounding death and the artifacts associated with them, such as urns and cemeteries, are intertwined with population geography considerations, and incorporating these elements into scientific analysis such as through artistic interventions holds great promise.

- Article

(11661 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Population geographers who aim to go beyond merely representing demographic data quantitatively focus on studying the practices of individuals within their social context. In the context of Bourdieu's (1977 [1972]) sociological theory, practice refers to a set of actions or behaviors that are performed by individuals or groups within a particular social field. Bourdieu (1977 [1972]) argues that these practices are informed by a shared set of cultural and social norms, values, and beliefs that are specific to that social field and that they are shaped by the unequal distribution of social, cultural, and economic capital among individuals and groups. He emphasizes the importance of practice in shaping social structures and reproducing patterns of inequality and argues that these practices are often invisible and taken for granted because they are so deeply ingrained in the habits and routines of everyday life. To understand social phenomena, Bourdieu (1977 [1972]) emphasized the importance of analyzing social practices within a particular field of social activity and identifying the cultural and social structures that shape those practices.

Qualitatively oriented population geographers follow Bourdieu's interest in practices and investigate, for example, inclusion and exclusion with respect to migration opportunities, nutrition, housing market preferences and disadvantages, work life, and healthcare practices, which can ultimately influence an individual's lifespan (see Preston, 1996; Caldwell, 1990; Rodrigues et al., 2022). Mortality, being a vital component of population development, plays a significant role in population studies. Traditionally, demographers research and discuss “death” primarily through statistical analyses of frequencies, causes, and spatial distribution (Caldwell, 2001). However, studying practices can significantly enhance the understanding of population dynamics in general (see Coast et al., 2009; Randall and Koppenhaver, 2004; Strong et al., 2023) and of mortality in particular as well as its embedding in a social context (see Crimmins et al., 2018; Plümecke et al., 2015). In addition, practices and their associated artifacts that facilitate coping with death experiences and memories of the deceased, such as urns and cemeteries, are essential aspects of individual and societal confrontations and practices with mortality, which have connections to population geography considerations (see Nash, 2018).

With the growing trend toward secularization and individualization since the 1990s (de Spiegeleer, 2019) as well as the increasing commercialization and competition in the funeral sector since the 2000s (see Akyel, 2013; Lares and Lehenbauer, 2019; Beard and Burger, 2020), cemeteries are no longer uncontested places. In Western countries, with increasing changes in society, there has been a change in funeral culture (Vanderstraeten, 2009). Although the outward appearance of most cemeteries and protocol procedures have changed little, numerous minor changes in burial practices, such as farewell rituals or burial locations, are already well underway. Current generations no longer seek to maintain and process the memory of the dead in a spatial and symbolic way, i.e., through graves and cemeteries, but rather rely on modern and postmodern means of pictorial reanimation of the deceased through photographs; videos; and, in recent years, increasingly through the internet, using virtual cemeteries and forms of commemoration (Macho and Marek, 2007).

Formerly taboo subjects such as death and mourning as well as funeral and burial rituals are increasingly being discussed in public (see Klingemann, 2022; Tschebann, 2022; Walter, 2012) and science. Mortality studies (see the journal Mortality, Mortality, 2023), death studies (see the journal Death Studies, Death Studies, 2023), and architecture and landscape planning (see Davis and Bennett, 2016; McClymont and Sinnett, 2021) offer interdisciplinary approaches to individual desires and social discourses on dying and burial. Population studies, despite their otherwise spatially based research interests, take little notice of burial sites and related debates, practices, and objects. But these shape unique places and sites, such as urns and cemeteries, where social differences in mortality and the causes of death are inscribed, much like archives (Collier, 2003).

Nevertheless, the ways in which cemeteries are avoided, used, or designed and the ways in which dying and death are staged reveal much about the population and its developments. Cemeteries are solemn places where the mortal remains of deceased individuals are laid to rest. Their graves, in turn, are visited, maintained, or even looted by contemporary citizens. These cemeteries may also be their future resting places. It is here that the simultaneity of different cultures of memory manifests itself. In a sense, they are landscapes of memory (Schama, 1995). In addition, they are also places where different moral values, religious beliefs, and social class differences become apparent (see Gade, 2005). They describe legal traditions, types of families and relationships, the social role of women, and migration histories, and they also define the financial value of urban real estate (see Straka et al., 2022). Thus, cemeteries and other places of remembrance hold significant cultural and historical value. By visiting cemeteries, we are confronted with the reality of our own mortality; they remind us of our collective past and offer an opportunity to reflect on our present circumstances.

In this contribution we will present an artistic intervention named DeathLab, which was conceived and carried out by Lydia Hamann, Mirko Winkel, and Karen Winzer in Berlin. The project aims to investigate how shifting values materialize in funeral culture through a physical manifestation. To do this, the organizers visited seven distinct locations across Berlin where death and funerals are an everyday topic, such as a crematorium, a sacral florist, and a coffin transport company. In a way similar to go-along (see Carpiano, 2009) and walk-along interviews (see Jonsson, 2021), the organizers invited the audience to join on a journey of exploration, to uncover and discuss their modern-day death culture (see Fig. 1). Thus, the project can serve as a source of inspiration for demographers and population geographers to broaden their understanding of death and dying beyond statistical representation of the deceased population. Rather, dying is intricately intertwined with various social practices that shape the way individuals, communities, and societies perceive and cope with mortality.

Berlin's Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Umwelt (2014) provides an overview of the developments: while in 1950 fewer than 40 % of the deceased in Berlin were cremated, in 2012 cremation already comprised 80 % of all burials. At least in the western part of Berlin, urn burial has been promoted since the 1960s, as during the division of the city there was a de facto shortage of cemetery space due to the limited urban area available. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, the reason for the trend toward cremation is likely to be the lower costs associated with the reduced space requirements, as there is now no longer a shortage of space. The gross space requirement for urn burial in shared installations (Urnengemeinschaftsanlagen) is 0.5 m2, for individual urn burials is 2.9 m2, and for coffin burials is 12.6 m2. Since the turn of the millennium, burial in shared urn installations, which were introduced in Berlin in 1976, has become more popular than burial in individual urn graves. For this reason, the project focused only on urns.

Before each event, a visual artist or artist collective was asked to design functional urns that took into account their established artistic style and the relevant themes. The resulting urns, which became our centerpieces, were diverse and served as a catalyst for discussing the theoretical and practical aspects of death, burial, the farewell process, and contemporary ritual culture (see Figs. 2–8). The urns are bearers of a death culture, and as Woodward (2019) and Bell and Bell (2012) conclude objects are mediators which can be used to talk about death culture.1 They are parts of a material culture embedded in situated contexts, gaining their meaning through their connection with specific practices (see Hodder, 1998). According to Schatzki (2016), they can be conceived as components of material arrangements that are intertwined with practices.

The material is part of social phenomena, it is constitutive of them; in fact it is inherent in these phenomena. (Schatzki, 2016:81; translated by the authors)

In addition to the functional aspect – safekeeping the ashes of the deceased – urns can also be seen as affect-generating artifacts (see Reckwitz, 2016) in the context of dealing with loss and death.

The conversations were accompanied by people who deal professionally with the end of life, such as funeral directors, politicians responsible for green infrastructure, ethnologists and cultural researchers, and the director of a museum of sepulchral culture. Based on their respective professions, the guests – together with the participating artists and the audience – explored the question of how new forms of expression can be developed in the face of death, mourning, and cremation and how changing views on death – also in the context of changing demographic structures, namely demographic aging (see BIB, 2021) – can be taken into account. It was also about the extent to which the art objects, which were designed differently from conventional mass-produced urns (see Fig. 9), could reveal certain underlying conflicts and provoke new cultural practices.

Alongside material artifacts like urns, music is an important part of the ritual practices at funerals. It is caught between the conflicting priorities of convention, cultural tradition, individual taste patterns as well as those attributed to the respective deceased person, and technical circumstances (see also Reinke, 2010). In order to take account of its significance and to develop further sensory and affective dimensions, there was a contribution to funeral music in each of the public sessions. Musicians from a variety of backgrounds made suggestions for new music that could be played at funerals: they interpreted songs of early deceased musicians on the organ; composed gentle electronic pieces; played farewell songs on alphorns, melancholic pop, or harrowing doom metal. They performed as soloists or in big bands.

In the following, we will describe the several events based on their thematic focus, the guests involved, and the specific discussions to provide an idea of what was happening. The titles of the events were “Politics and ashes”; “Eternal fire”; “Under trees”; “Death and form”; “How to say goodbye”; “Beyond family”; and “Faith, love, hope”.

2.1 Politics and ashes

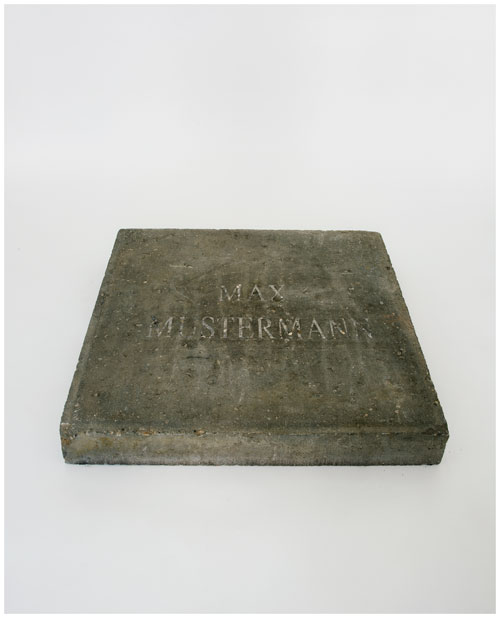

The question of who is responsible for the dead was discussed with the head of the department responsible for all of Berlin's cemeteries and parks, a politician from Bremen who was responsible for liberalizing the law, and an undertaker who specializes in burying young people. The urn by artist Axel Loytved (see Fig. 2) is a do-it-yourself guide. It explains how to mix the ashes of the deceased with cement, water, and sand to make a standard size concrete cobblestone that can be laid. In view of the sculptor's radical burial proposal, the opening event discussed the extent to which one can do justice to the increasing individualization of forms of farewell and still maintain a critical attitude toward the privatization of the resting place of the dead. The event took place in the farewell hall of the Crematorium Baumschulenweg, which was opened in 1999. More than 600 corpses were lying in the basement of the sacral-looking yet highly functional béton brut crematorium at the time of the discussion. The cremation process is computerized and largely performed by robots. The heat from the cremation warms the multi-confessional mourning rooms above.

2.2 Eternal fire

What role do fire and smoke play at the end of life? Kerstin Stoll presented her ceramic urn (see Fig. 3), which can actually smoke and thus requires a certain ritual practice. Based on her artistic research in Laos and Cambodia, she reported on her enthusiasm for the enigma of monumental stone urns and the relationship between spirits and human beings that she encountered there. Thailand is the geographical focus of ethnologist Benjamin Baumann's research, too. He has lived there, attended funerals, and documented how the dead and their souls are treated. The two discussed how burial objects can be classified as cultural and historical carriers of knowledge in our society and in a global context. What is the significance of rituals and artifacts that are understood only in a certain part of the world or by a small group? It was also a question of whether other cultural practices could take place at all in communal cemeteries or whether the bodies would have to be repatriated. The venue was the chapel and the glass house next to the burial hall at the Friedrichswerder Cemetery. The glass house served as a waiting room before the burials.

2.3 Under trees

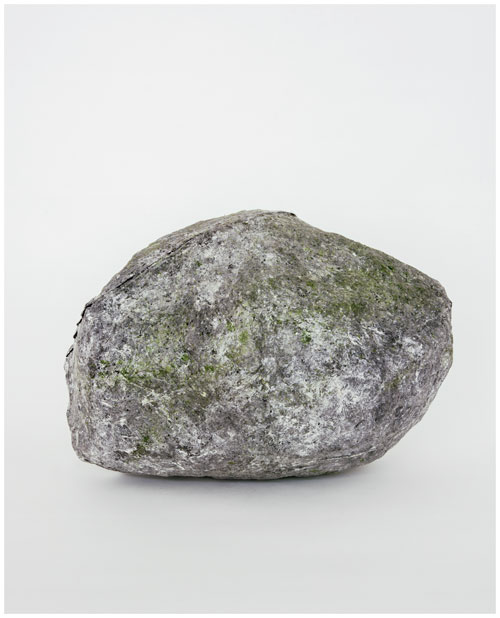

Private cemetery forests or resting forests are promoted as burial sites in a living environment, providing a return to nature in former working forests. The idea of a cyclical connection between life and death, the question of what was before life and what comes after life, is of interest to many people, regardless of their cultural or religious background. In her work, artist Stefanie Bühler explores the artificiality of nature and landscape. Her urn deceptively imitates a stone (see Fig. 4). She has developed a material recipe of cellulose flakes, sugar, corn starch, color pigments, and wax that allows her to create a very light yet stable, ecologically degradable form. The ash capsule (in which the ashes are placed as standard by the crematorium) is almost camouflaged by this equally natural and artificial form. The conversation took place between her and a forest scientist who is also on the board of RuheForst GmbH, a company that specializes in resting forests. The discussion focused on the invisibility and displacement of the dead from urban areas to distant forests and the role of increasingly empty cemeteries in ever more densely populated cities. The venue for the event was the Weyer flower shop, now in its third generation of family ownership. After opening as a fruit and vegetable shop, the assortment was increasingly changed to funeral floristry.

2.4 Death and form

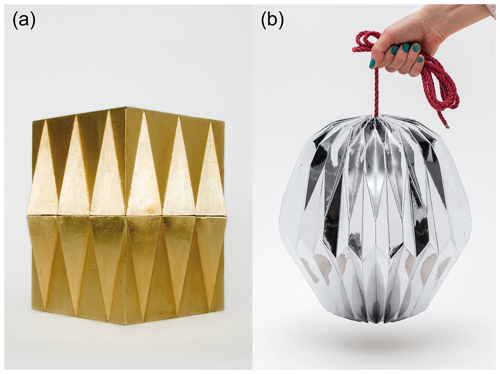

The artists Jadranko Barišić and the duo Renée and Thomas Rapedius use gold and silver in the design of their urns – colors and materials that radiate value and want to be seen (see Fig. 6). For the icon painter Barišić, however, it is clear that figures with religious significance cannot be depicted on his urn, which is covered with gold leaf; after all, saints cannot be buried in the ground. The artist duo Rapedius, on the other hand, developed a glittering paper urn reminiscent of a lantern or a disco ball. Using the collection of the Kassel Museum of Sepulchral Culture, which is dedicated to the cultural history of burial, as a backdrop, the director of the museum talked to the artists about the transformation of value through materials and also explained the change in design traditions using the example of gravestone design in the cultural region of Germany. The former caretaker's house of the St. Marien and St. Nikolai Cemetery, where the event took place, is occupied by a non-profit association. Its members organize readings, show exhibitions, collect herbs, and try to raise awareness of the cemetery as an inner-city biotope.

2.5 How to say goodbye

Andreas Eschment has developed an urn that addresses the productive power of performative acts in the mourning process. He cuts, perforates, and sews the individual parts of the urn's shell out of wool felt (see Fig. 5). He works the curved brass brackets into the seams needed to lower the urn into the ground. Two lids can be used to create a lockable compartment above the ash capsule in which mourners can place significant items: food, letters, mementos, and flowers. Theologian Oliver Wirthmann discussed the scope for individualized forms of burial and the establishment of new rituals, drawing on his experience as a teacher of aspiring undertakers at the Bundesausbildungszentrum der Bestatter. As the need for personal, non-denominational solutions grows, it is important to prepare future undertakers for their new tasks with knowledge of old traditions: how can a ceremony be created that can be understood by multiple generations? What new rituals are emerging beyond religious traditions? What effect does a ready-made ceremony have on a personal approach to dying, death, and mourning? They discussed to what extent Andreas Eschment's urn could help here and also tried out the urn in a very practical way with the audience. The K-Salon is both an art gallery and the home of the Kiez-Bestattungen funeral home. The ultra-local funeral service focuses on the undertaker's extended circle of friends and the immediate Kreuzberg neighborhood. Berlin's youngest funeral home is located next to the city's oldest gravestone workshop.

2.6 Beyond the family

What historical, political, and social values are represented by the tradition of family graves? And how do lesbian, gay, and queer ways of life manifest themselves in the cemetery? The artist Jeuno JE Kim built a glass urn (see Fig. 7). It is literally about a “transparent” approach to one's own remains and about making attitudes and lifestyles visible beyond death. Her interviewee, Susanne Jung, runs a funeral home called Funeral Ladies. She is particularly interested in the role of women in cemeteries: both their visibility in cemeteries in the past, for which she offers themed walks, and their support of the SAFIA association, which founded Germany's first lesbian cemetery in 2014. Another guest, Bernd Bossmann, runs the oldest cemetery café in Germany. He is particularly committed to the so-called Garten der Sternenkinder, a section of the cemetery where stillborn or miscarried children can be buried. As a gay activist, he follows the development of queer death culture and empowerment movements. He spoke about the communal burial of AIDS victims in disused historical family graves and the new burial rituals that emerged when friends had to bury each other. The event took place in the chapel of the progressive Christian congregation 12 Apostles, which is committed to addressing funeral traditions and reactivating cemetery culture with a very engaging program.

2.7 Faith, love, hope

Artist Franziska Nast explores the culture and practice of tattooing. Her tattoos cover skin as well as walls and urns (see Fig. 8). She takes traditional tattoo symbols and combines them with personal images. The question of what images and texts a person wants to wear on their body until the end of their life is crucial to every tattoo. But when the body is cremated, the symbol created for eternity disappears. Franziska Nast looked at this moment and asked what messages are still important to us after death and what forms they can take. Together with the cultural scientist Thomas Macho and the tattooed undertaker Eric Wrede, she discusses the idea of eternal drawing, the notion of immortalization, and the question of what meaning art can have in the face of death. The event took place at the coffin transport company Gustav Schöne in Berlin-Rixdorf, a family business that has been in existence for almost 130 years. In the event of death, the employees are responsible for transporting the deceased. They provide a dignified farewell in a variety of vehicles, from horse-drawn carriages to fully equipped Mercedes with an LED starlight sky. The DeathLab uses the large mourning hall where farewells and funerals are usually held.

Today's cemeteries are increasingly losing their function as places of mourning, as more and more people die without relatives to mourn them or as the increasing mobility of people's homes often makes it impossible to visit the graves of their loved ones. The care of the graves is then taken over by grave care companies.

In addition to personal circumstances, debates about death, dying, and burial are also shaped by administrative conditions. In Germany, an elaborate system of regulations and laws governs the treatment of the deceased; binding standards control burial and final rest. Unlike many other European countries, there is a legal requirement that ashes cannot leave the cemetery. These conditions include legal and regulatory frameworks, institutional policies, and cultural norms that influence how death-related issues are discussed and addressed within society. This is due to the large number of cemeteries; the change in the use of space after the fall of the Berlin Wall; the decline in the number of deaths; and the high fees that encourage people to choose an urn instead of a coffin, which would take up more space, or to go directly to the resting forest. But Berlin is also a place of migrants from Germany, Europe, and other parts of the world, which means that many people choose to be buried where they originally came from. In order to ensure occupancy and avoid closing the cemeteries, municipal and church cemetery operators are meeting the diverse needs of these new groups. Some people are concerned that the familiar homogeneity of cemeteries is tending to dissolve. For others, the new, more diverse forms of burial and mourning better reflect current demographic changes.

In discussions with visitors to the DeathLab, it became clear that the cemetery culture of the future will not only be a culture of visible differences. Rather, people want to find participatory forms of burial and mourning. Only in this way can the cemetery remain an object of identification in the future. But it will not be limited to urban spaces. With increasing deregulation, the trend is moving strongly into the private sphere. In the future, urns will certainly be placed more often in living rooms, ashes will be scattered in gardens or by lakes, or mourning will move directly into virtual spaces. Only time will tell whether this is a continuation of the long-lamented repression of death or a new way of appropriating death and making it visible.

The artists' examples and the thematic diversity of DeathLab correspond to the increasing and very different tendencies toward individualism, anonymity, or ecological sensibility, which are reflected not only in the society of the living, but also in the forms of burial. The spatial demarcation and exclusion of bourgeois modernity, particularly evident in cemeteries that have been moved to the outskirts of the city and made invisible, are countered by new places and forms of burial and commemoration that are tied to the spaces of the living.

According to the authors, a newly conceptualized and broadened population geography offers room for an examination of the relationship to death and dying – analogous to the examination of attitudes toward family and offspring in the study of fertility and generative behavior. Accordingly, practices carried out in the context of farewells to the deceased and mourning can also become the object of investigation. They experience a specific geographical relevance not least through their contribution to the (re)production of spatial constellations, which is reflected in the creation of places of remembrance and mourning.

Taking a closer look at artistic forms of dealing with death, mourning, and farewell is without a doubt a rather unusual approach to this topic. The investigation of artistic practices and processes can be understood here in terms of artistic research, focusing on artists in their capacity as “reflexive practitioners” (Joly and Warmers, 2012:IX) and focusing not only on their finished works, but also on processes of work creation (see Tröndle, 2012:170). In analogy to and following a concept of “critical mapping as an artistic research mode” (Bauer and Nöthen, 2022), artistic processes can be interpreted and used as specific cognitive processes also in the topic discussed here. They can help “(1) systematically assemble modes of perception from various fields of experience; (2) relate them in open-ended, collaborative processes, questioning them, for example, in terms of material and social preconditions and possibilities; and (3) develop re-imaginations” (Bauer and Nöthen, 2022:166; translated by the authors) that can offer alternative facets and forms of mourning and memory culture as well as the spatial productions linked to them. The forms of artistic expression that are brought into view, which make both actual and possible positions on a phenomenon visible, thus contribute to a special production of knowledge (see Rose, 2015). With regard to school and university teaching in population geography, this condensation of different experiences on the one hand and the thinking of alternatives on the other hand can also be seen as a special didactic approach to dealing with death and relations to death.

No data sets were used in this article.

Project idea and implementation were done by MW. Theoretical frame was provided by MS and JW. Composition of the text was by MW and JW with additional sections by MS. Editing was by MW and JW.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This paper was edited by Nadine Marquardt and reviewed by one anonymous referee.

Akyel, D.: Die Ökonomisierung der Pietät: der Wandel des Bestattungsmarkts in Deutschland, Campus-Verl, Frankfurt am Main, 239 ff., https://pure.mpg.de/rest/items/item_1752561_7/component/file_3070325/content (last access: 17 October 2023), 2013.

Bauer, L. and Nöthen, E.: Kritisches Kartieren als künstlerischer Forschungsmodus, in: Handbuch Kritisches Kartieren, edited by: Dammann, F. and Michel, B., transcript, Bielefeld, 157–168, ISBN 978-3-8376-5958-0, 2022.

Beard, V. R. and Burger, W. C.: Selling in a Dying Business: An Analysis of Trends During a Period of Major Market Transition in the Funeral Industry, OMEGA – J. Death Dying, 80, 544–567, https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222817745430, 2020.

Bell, M. E. and Bell, S. E.: What to Do with All this “Stuff”? Memory, Family, and Material Objects, Storytelling, Self, Society, 8, 63–84, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41949178 (last access: 17 October 2023), 2012.

Berlins Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Umwelt: Bericht zum Stand der Umsetzung des Friedhofsentwicklungsplans (FEP) 2006, 2014.

BIB – Bundesinstitut für Bevölkerungsforschung (Ed.): Fakten zur demografischen Entwicklung Deutschlands 2010–2020, Wiesbaden, https://www.bib.bund.de/Publikation/2021/pdf/Fakten-zur-demografischen-Entwicklung-Deutschlands-2010-2020.pdf (last access: 13 March 2023), 2021.

Bourdieu, P.: Outline of a Theory of Practice, Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511812507, 1977 [1972].

Caldwell, J. C.: Cultural and Social Factors Influencing Mortality Levels in Developing Countries, Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Social Sci., 510, 44–59, 1990.

Caldwell, J. C.: Demographers and the study of mortality: scope, perspectives, and theory, Ann. NY. Acad. Sci., 954, 19–34, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb02744.x, 2001.

Carpiano, R. M.: Come take a walk with me: The “Go-Along” interview as a novel method for studying the implications of place for health and well-being, Health Place, 15, 263–272, 2009.

Coast, E., Mondain, N., and Rossier, C.: Qualitative research in demography: quality, presentation and assessment, in: XXVI IUSSP International Population Conference, 27 September–2 October 2009, Marrakech, Morocco, 2009.

Collier, A. C. D.: Tradition, Modernity, and Postmodernity in Symbolism of Death, Sociolog. Quart.. 44, 727–749, 2003.

Crimmins, E. M., Shim, H., Zhang, Y. S., and Kim, J. K.: Differences between Men and Women in Mortality and the Health Dimensions of the Morbidity Process, Clin Chem., 65, 135–145, https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2018.288332, 2018.

Davies, P. J. and Bennett, G.: Planning, provision and perpetuity of deathscapes. Past and future trends and the impact for city planners, Land Use Policy, 55, 98–107, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.03.029, 2016.

Death Studies: https://www.tandfonline.com/journals/udst20, last access: 17 October 2023.

de Spiegeleer, C.: Secularization and the modern history of funerary culture in Europe. Conflict and market competition around death, burial and cremation, Trajecta, 28, 169–201, 2019.

Gade, D. W.: Cemeteries as a Template of Religion, Non-religion and Culture, in: Stanley D. Brunn The Changing World Religion Map. Sacred Places, Identities, Practices and Politics, Springer, 623–647, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9376-6_31, 2005.

Hodder, I.: The interpretation of documents and material culture, in: Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials, edited by: Denzin, N. K. and Lincoln, Y. S., SAGE, Thousand Oaks, 110–129, ISBN 978-1-4833-4980-0, 1998.

Joly, J.-B. and Warmers, J.: Künstler und Wissenschaftler als reflexive Praktiker – Ein Vorwort, in: Kunstforschung als ästhetische Wissenschaft. Beiträge zur transdisziplinären Hybridisierung von Wissenschaft und Kunst, edited by: Tröndle, M. and Warmers, J., transcript, Bielefeld, IX–XII, ISBN 978-3-8376-1688-0, 2012.

Jonsson, E.: The living in a place for the dead. An exploration of place as assemblage, MS Thesis, Department of Human Geography, Lund University, Lund, https://lup.lub.lu.se/luur/download?func=downloadFile&recordOId=9064227&fileOId=9064230 (last access 17 October 2023), 2021.

Klingemann, H.: Cemeteries in transformation. A Swiss community conflict study, Urban Forest. Urban Green., 76, 127729, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127729, 2022.

Lares, J. D. and Lehenbauer, K.: Funeral services: the silent oligopoly an exploration of the funeral industry in the United States, RAIS – J. Social Sci. Res. Assoc. Interdisciplin. Stud., 3, 18–28, 2019.

Macho, T. and Marek, K.: Die neue Sichtbarkeit des Todes, Fink, München, ISBN 9783770544141, 2007.

McClymont, K. and Sinnett, D.: Planning cemeteries: their potential contribution to green infrastructure and ecosystem services, Front. Sustain. Cities. Sec. Urban Green., 3, 1–17, https://doi.org/10.3389/frsc.2021.789925, 2021.

Mortality: Promoting the interdisciplinary study of death and dying, https://www.tandfonline.com/journals/cmrt20, last access: 17 October 2023.

Nash, A.: That this too, too solid flesh would melt: Necrogeography, gravestones, cemeteries, and death scapes, Prog. Phys. Geogr., 42, 548–565, https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133318795845, 2018.

Plümecke, T., Mikosch, H., Mohrenberg, S., Supik, L., Bartram, I., Ellebrecht, N., Nieden zur, A., Schnieder, L., and Rose, A.: Sichtbarmachung als Wissensproduktion. Zur künstlerischen Methode der Enzyklopädie der Handhabungen, in: LaborARTorium. Forschung im Denkraum zwischen Wissenschaft und Kunst. Eine Methodenreflexion, edited by: Jürgens, A.-S. and Tesche, T., transcript, Bielefeld, 199–212, ISBN 978-3-8376-2969-9, 2015.

Preston, S. H.: Population Studies of Mortality, Populat. Stud., 50, 525–536, 1996.

Randall, S. and Koppenhaver, T.: Qualitative data in demography: The sound of silence and other problems, Demogr. Res., 11, 57–94, 2004.

Reckwitz, A.: Praktiken und ihre Affekte, in: Praxistheorie, edited by: Schäfer, H., transcript, Bielefeld, 163–180, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839433454-005, 2016.

Reinke, S. A.: Musik im Kasualgottesdienst. Funktion und Bedeutung am Beispiel von Trauung und Bestattung, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen, ISBN 10 3525601271, 2010.

Rodrigues, W., da Costa Frizzera, H., Trevisan, D. M. Q., Prata, D., Reis, G. R., and Resende, R. A.: Social, Economic, and Regional Determinants of Mortality in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 in Brazil, Front Publ. Health, 31, 856137, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.856137, 2022.

Rose, A.: Sichtbarmachung als Wissensproduktion. Zur künstlerischen Methode der Enzyklopädie der Handhabungen, in: LaborARTorium. Forschung im Denkraum zwischen Wissenschaft und Kunst. Eine Methodenreflexion, edited by: Jürgens, A.-S. and Tesche, T., transcript, Bielefeld, 199–212, ISBN 978-3-8376-2969-9, 2015.

Schama, S.: Landscape and memory, edited by: Knopf, A. A., Random House, New York, ISBN 10 0679735127, 1995.

Schatzki, T.: Materialität und soziales Leben, in: Materialität. Herausforderungen für die Sozial- und Kulturwissenschaften, edited by: Kalthoff, H., Cress, T., and Röhl, T., Wilhelm Fink, Paderborn, 89–101, ISBN 978-3-8467-5704-8, 2016.

Straka, T. M., Mischo, M., Petrick, K. J. S., and Kowarik, I.: Urban Cemeteries as Shared Habitats for People and Nature: Reasons for Visit, Comforting Experiences of Nature, and Preferences for Cultural and Natural Features, Land, 11, 1237, https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081237, 2022.

Strong, J., Nandagiri, R., Randall, S., and Coast, E: Qualitative research in demography: marginal and marginalized., in: How to Conduct Qualitative Research in Social Science, Chap. 9, edited by: Liamputtong, P., Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/118028/ (last access: 17 October 2023), 2023.

Tröndle, M.: Methods of Artistic Research – Kunstforschung im Spiegel künstlerischer Arbeitsprozesse, in: Kunstforschung als ästhetische Wissenschaft. Beiträge zur transdisziplinären Hybridisierung von Wissenschaft und Kunst, edited by: Tröndle, M. and Warmers, J., transcript, Bielefeld, 169–198, ISBN 978-3-8376-1688-0, 2012.

Tschebann, S.: Cemetery Enchanted, Encore: Natural Burial in France and Beyond, in: Interdisciplinary Explorations of Postmortem Interaction. Dead Bodies, Funerary Objects, and Burial Spaces Through Texts and Time, edited by: Weiss-Krejci, E., Becker, S., and Schwyzer, P., Springer, 249–268, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-03956-0_11, 2022.

Vanderstraeten, R.: Modes of Individualisation at Cemeteries, Sociolog. Res. Online, 14, 10, https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.1972, 2009.

Walter, T.: Why different countries manage death differently: a comparative analysis of modern urban societies, Br. J. Sociol., 63, 123–145, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127729, 2012.

Woodward, S. (2019): Material Methods: Researching and Thinking with Things. London: SAGE.

As a result of extensive media coverage, a publication (http://www.finaleform.de/en/deathlab, last access: 17 October 2023) was produced documenting the discussions and the urns. In addition, a not-for-profit project has been set up to sell a selection of artists' urns under the name Finale Form (same link as above). The following is a brief description of the various urns created for the public encounters and the themes addressed.