the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Too little to live, too much to die: governing asylum seekers on the brink of death in Moria, Lesvos

Tobias Breuckmann

For some time now, discussions in border studies have revolved around the biopolitical functions of refugee camps. From one perspective, the camps can be perceived to be humanitarian institutions. From another perspective, they can be considered institutions of necropolitics that allow asylum seekers to die, although they do not actively kill them. However, my own ethnographic research on Lesvos from 2018 to 2020 has shown that the biopolitics regulating refugee migration is not always situated at one of these extremes: for a long time, many asylum seekers have been maintained on the brink of death. Herein, I use governmentality theory and relational geography to examine how stabilization at this extremely fragile threshold has been maintained. I identify various strategic socio-spatial technologies that have been implemented on Lesvos and elucidate how heterogeneous power techniques were combined and practically related to each other in order to stabilize these modes of governing. This article also demonstrates how analysing modes of governing in relation to local spatial practices expands existing concepts by drawing a more complex and nuanced picture of power relations.

- Article

(2469 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

So, the next morning, I was still sleeping, and one Nigerian guy came and knocked at my door and said, `Hey, this guy is dead, this guy passed away last night due to the cold.' … And he is not the first person, he is not the second, but at least, something like this should end. A lot can be done, but some basic, at least basic things, like water, heat, at least. (I11, 2019)

Between 2015 and October 2020, the Greek refugee camp Moria on the island of Lesvos lost many residents due to freezing temperatures, dehydration, fires, disease, and violence (see Córdova Morales, 2021). The resident's statement quoted above highlights the omnipresence of death in the everyday life of the camp. Furthermore, the quote's conclusion highlights the fact that the camp's residents believed this was not a chance circumstance but the result of circumstances that had persisted for years due to the insufficient support and protection provided by the authorities and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). In this article, I propose that the persistent threat of death and precarious living conditions within the camp were the result of the uneven local power structures and asymmetrical negotiations that emerged in relation to migration policies at various geographical scales.

Previous research on refugee camps has primarily focused on the political production of conditions for living and dying from two distinct perspectives, while conceptualizing refugee camps as biopolitical instruments for the management of migration (Felder et al., 2014:365). The first group of researchers considers the first concept of biopolitics to be the political production of a population's lives (see Foucault and Macey, 2003) and assumes that such camps are established to provide life-sustaining care for refugees while keeping them under control (see Hoffmann, 2015). In this context, refugees are presented as both a threat to a state's population and in need of protection, and they are treated accordingly (see Mavelli, 2017). In contrast, the second group of researchers ascribes to the theory of necropolitics (see Mbembe, 2003) and views refugee camps as places where actors implement power techniques to inflict harm and cause death (see Zena, 2019). In such cases, biopolitical rationales are directed towards protecting the state's population, even if that means exposing refugees to deadly conditions (Wilson et al., 2023:2). However, although several refugees died in Moria each year, the situation at Moria does not fit this dichotomous classification; with its refugees living on the threshold of death, it is best classified as a midpoint on a scale between these two extremes. When grappling with this threshold between living and dying, scholars of geography and camp studies turn to Mbembe's construct of the “living dead”: subjects who are still alive yet are constantly suffering on the brink of death for political ends (Mbembe, 2019:91). In their research, such scholars have focused on state violence in detention centres (see O'Donnell, 2022), the “active inactivity” of institutions withholding provision of crucial services (see Davies et al., 2017; see also Themann, 2025), technologies for keeping inmates alive through medical services and NGO support (Martin et al., 2020), and survival as an act of resistance. These are all important vantage points from which to examine the particular situation in Moria, but instead, previous studies have often focused on isolated actors, such as the state or NGOs, or specific techniques. However, it is also important that camp studies conceptualize and consider detention camps as a contingent interplay of fragmented sovereignties, heterogeneous actors, agency, and resistance (see Feldman, 2015; Oesch, 2017). Therefore, in this study, I examine the often-dynamic power relations and how they were stabilized through the negotiations between various actors, their power techniques, and the technologies that emerged. Accordingly, the primary questions for this study are as follows:

-

How did the power negotiations at Moria localize the refugee population there on the brink of death?

-

How did European and national migration policies capitalize on this situation?

I have used the lens of governmentality theory to answer these questions, focusing on technologies and their relational geographies. I provide a detailed explanation of these concepts in the following section. After presenting the methodology and scope of the research, I discuss the technologies through which the camp's population was situated on the brink of death. I also explain how the effects of the technologies were strategically capitalized on at various political scales. This article demonstrates that a detailed analysis of the modes of governing that rely on local power techniques can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of biopolitics and necropolitics. In so doing, it contributes to the geographic analysis of the government of migration and asylum, as well as to the conceptualization and investigation of refugee camps as places of biopolitics and necropolitics in critical migration studies. Furthermore, the article makes a conceptual contribution to the spatial analysis of governmentalities.

The post-structuralist theory of governmentality, which gave rise to the concepts of biopolitics and necropolitics, facilitates the analysis of power relations and their impact on the living (and dying) conditions in refugee camps. The theory generally examines modes of governing as the coordination of institutions and actors working to influence populations in line with specific rationales (Lessenich, 2003:81). The European migration regime can be considered a mode of governing that involves various attempts to control and contain mobile populations in line with the rationales of states and institutions such as the EU (Pott, 2018:109). However, in order to implement governing strategies, power techniques must be established and contextualized locally (Foucault, 2003:398). Power techniques are specific, small-scale practices intended to affect people and the circumstances under which they operate (Manderscheid, 2012:148). In order to produce significant power effects, they must interact with a set of other power techniques and, thus, be part of a widespread relational network of techniques that unevenly position people in the field. In post-structuralist theory, these sets of techniques and their relational networks are referred to as technologies (Dean, 1996:55). Technologies evolve from the practices of negotiation and co-production practices of the various actors within the network, as well as from attempts to coordinate techniques for strategic purposes (Allen, 2003:121). However, it is essential to be aware that technologies also have their own materiality and generate unforeseen effects. These effects interact with other technologies and must be adapted to by any entities acting in the field (Bussolini, 2010:91).

Building on previous studies on power technologies within migration regimes (e.g. Oesch, 2017; Salmenkari and Aldawoodi, 2024; Tazzioli, 2022), I created an analytical grid that can be used to record the most important techniques and the mutually stabilizing relationships that combine to form technologies (see Breuckmann, 2024). In order to do this, I combined the concept of power technologies with relational theories of geography. According to Massey (1992:70), space is not just a static, physical construct. Space, like power relations, is produced by the actors, materialities, and practices, as well as their interactions and relationships with each other. Actors in certain positions are able to impose power techniques on other people, using their location as well as materialities such as physical barriers, databases, and weapons within their reach. Therefore, by recording spatial practices, it is possible to come to a better understanding of the execution of power techniques, the resources involved, and their effects (see Breuckmann, 2024). In addition, this approach helps us analyse the interplay between different techniques that constitute technologies by either identifying their practical connection, for example, when they are executed at the same place, or documenting intermediate practices and materialities that connect power techniques with their effects over distances by applying geographical network theories (Murdoch, 2006:66). Furthermore, it is also possible to locate the strategic positions from which actors attempt to influence other actors and the interplay between techniques in order to influence the overall technologies within these networks of relational–spatial relationships using post-structuralist theories of scale (see Breuckmann, 2023). Therefore, augmenting the concept of technologies with theories of relational space helps us analyse the practical constitution, stabilization, constant negotiation, and adaptation of power relations on a local level and helps us identify attempts to strategically influence and coordinate technologies on different scales.

The Moria camp, which was previously a deportation detention facility, was officially established as the Reception and Identification Centre, Lesvos, in 2015. It was located in the island's southeast, on an army base (Hänsel, 2019:32). In response to extensive migration movements to Greece and the temporary destabilization of the Schengen regime in 2015 (Hess et al., 2017:11), the EU and its member states implemented the hotspot mechanism. Together with the EU–Türkiye deal of 2016, with which EU officials intended to enable comprehensive deportation of asylum seekers from Greece to Türkiye (Tsoni, 2016:36), the hotspot mechanism made five Aegean islands a central point from which authorities could attempt to control migration in southeastern Europe (Kuster and Tsianos, 2016:6). Following its establishment as a hotspot centre, Moria functioned as a central hub where people arriving on Lesvos were housed and registered, and their asylum applications were processed. Since the coalition elected in 2015 and led by the left-wing party Syriza had to wind back its progressive asylum politics in favour of re-stabilizing the Dublin system, its policies have been characterized by the systematic abandonment of refugees and by delays in asylum processing (see Skleparis, 2017). In contrast, the conservative party, Nea Dimokratia, elected in 2019 attempted to accelerate asylum procedures and reduce basic support in order to raise the number of deportations (see Hernàndez, 2020).

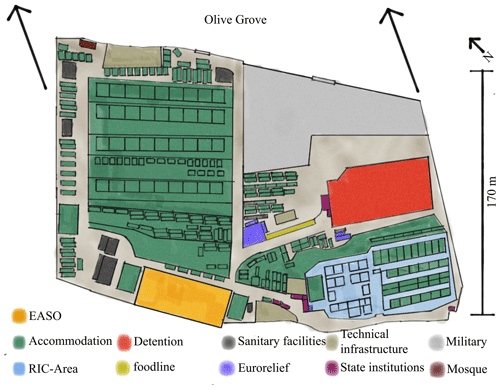

The camp was situated on a hillside, surrounded by olive groves that were increasingly occupied by the arriving asylum seekers who built a big, informal camp. The formal camp consisted of several zones and levels (see Fig. 1), including two zones that were surrounded by high barbed-wire fences and to which the asylum seekers' access was strictly regulated by police and security guards.

The first such zone was the RIC Area (Reception and Identification Centre Area), which housed various institutions responsible for the registration of newly arriving migrants and the office of the Ministry of Health, responsible for vulnerability assessments, as well as housing structures for new arrivals and vulnerable groups. The second closed zone was the EASO Zone, where institutions like the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) and the Greek Asylum Service conducted pre-interviews and managed the actual asylum procedures. While the camp was officially run by Greek officials, several NGOs helped maintain the camp's infrastructure by fulfilling tasks such as allocating housing and distributing supplies. As all of the Greek and EU institutions were located within the closed zones, some NGOs were the only contact point for asylum seekers. The main NGOs were Eurorelief, a Christian organization that was responsible for most of the housing and non-food-item supply and had an information point in the centre of the camp; Refugees 4 Refugees (R4R), a refugee-founded NGO that was responsible for housing and food supplies outside the camp; and various medical NGOs including the Boat Refugee Foundation and Kitrinos, both of which were located in the closed areas. However, the camp was entirely destroyed by fire in the autumn of 2020 (Hernàndez, 2020: n.p.) and was replaced by the temporary camp in which the asylum seekers on Lesvos are still living (mare liberum, 2024: n.p.). During its operation, the living conditions in Moria were characterized by neglect, unsanitary conditions, and violence, all of which caused numerous deaths (see Córdova Morales, 2021).

I identified the power techniques and the interactions between them occurring in and around the camp while conducting ethnographic research during five field trips of varying lengths (3 to 8 weeks) between 2018 and 2020. The data I gathered during these trips include expert interviews with NGO staff, activists, and government employees (11 interviews), as well as narrative interviews with asylum seekers living in and around Moria (18 interviews) (cited as “I” in the text) (see Charmaz, 2014). Due to the difficulty gaining access to the field, I mainly relied on meeting potential interview partners during my observations, although I did also use targeted approaches, primarily when contacting institutional and NGO staff, whom I selected based on their roles in running the camp. In addition, I conducted participatory and non-participatory observations, both inside and outside the camp (cited as “B” in the text). For example, I worked with NGOs and met with asylum seekers in both the informal camp “Olive Grove” and the NGOs' offices (see Deppermann, 2014).

As Moria was a very precarious ethnographic field with extremely uneven power relations, I had to reflect on my own position, fieldwork practices, and methods in a special way. During the fieldwork phases, I had to navigate various contradictions resulting from my political aim to analyse and make the conditions and mechanisms actively threatening the lives of asylum seekers transparent while gaining field access by working with the NGOs that were involved in perpetuating these very conditions. I used the reflexive concept of complicity (Becker and Aiello, 2013) in order to weigh my own contribution to the living conditions in the camp against the positive effects my research may have on the situation for asylum seekers in the future and situationally adjust my field practice. In addition, I had to be aware of the personal power relations during my interviews with the asylum seekers and the possibility that the situation may lead to re-traumatization or destabilization. Therefore, I used interview formats where asylum seekers could choose their own thematic focus and pointed out repeatedly that they did not have to go into detail about any topic if they did not want to (Charmaz, 2014). I also endeavoured to be as transparent as possible about my research goals and the voluntary nature of the interview and have maintained contact with people who wanted to keep in touch (Clark-Kazak, 2017). I supplemented the data collected on site with documents, including legal texts, policy papers, and organization reports. I then analysed the data using situational maps and grounded theory (see Clarke et al., 2018). In the course of this work, I identified several technologies that were interacting with each other and, thus, constituted the camp's power relations.

Two key technologies were developed during the implementation of the hotspot mechanism and the EU–Türkiye agreement at the local level. The first technology related to the registration of asylum seekers and their restriction to the island by preventing them from travelling without proper documentation. The second technology involved the regulation of their access to asylum processes. The island's strategic location on the central migration route from Türkiye to the EU was essential to the first technology. This technology involved picking up asylum seekers at sea or on the coast and transporting them to Moria and directly to the RIC Area for registration (I5, 2018; I18, 2020). En route to Moria, the asylum seekers could be temporarily held at the interim United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) camp in the island's north or at a facility near Mytilene. Both during this transit and while being housed in the RIC Area at Moria during the registration process, the asylum seekers were restricted to fenced and closed areas to prevent them from leaving the island undocumented. Then, after determining their identity and completing the registration process, they were issued an ID card that restricted their mobility to either Lesvos or Greece based on their vulnerability status (B4, 2019). By checking people's ID cards at the exits from the harbour and the airport, using fences and gates for security checks, and relying on the great distance from the mainland as a fallback, it was generally possible to ensure that asylum seekers did not leave the island unregistered or without permission, meaning that their only options were to go through the asylum procedure or be deported (I2, 2018).

The second technology regulating access to asylum processes produced an initial delay followed, in 2020, by a sudden acceleration in the asylum procedure. The temporal structuring was coupled with strict restrictions, spatially and otherwise, around access to assistance systems or a status that would facilitate access to asylum. In turn, this led to high initial rejection rates (Greek Council for Refugees, 2020; I12, 2019; I16, 2019). Both the restriction of the mobility of asylum seekers to Lesvos and the long delays in processing their claims resulted in constant overcrowding at the camp. Above all, this overcrowding led to a precarious accommodation and supply situation (Aegean Boat Report, 2021:1). I now turn to the sub-technologies that evolved out of these two main technologies in order to stabilize them and keep most asylum seekers alive but on the brink of death.

4.1 Technologies of supply

The systems in place for distributing provisions among the asylum seekers played a central role in the governing of the camp. In the following, I focus on the provision of food and medical care, specifically because of the significant impact these services had on the living conditions in the camp.

The supply technology and its spatial organization developed, fundamentally, under the circumstances of the severe overcrowding of the camp and the insufficient funding provided by the Greek state and the EU, which resulted in an extreme scarcity of supplies. State organizations and NGOs responded to these conditions in different ways. Both mainly used central issuing points with routing systems where asylum seekers had to queue (I1, 2018) but with different outcomes due to the power techniques that were grouped around these issuing points. For example, the central food line was run by the Greek army in cooperation with a caterer. However, while distributing the food, army staff did not respond when people jostled each other or when conflicts arose (I11, 2019). Furthermore, the officials seldom documented who had already received food. As a result, the official records did not accurately reflect the supply needs of the camp's population (I10, 2019). Instead, the power techniques of the supply organized by the state institutions were characterized by active non-regulation and strategic non-documentation, leading to undersupply and (sometimes extensive) conflicts within the camp (I9, 2019).

Supplementing the state's inadequate food supply fell to the NGOs and asylum seekers, who were allocated the responsibility for supply or were allowed to provide for themselves. For example, R4R and Movement on the Ground took over the food supply in the informal Olive Grove camp and set up power techniques to track who received food and avoid large gatherings whenever possible. They implemented IDs for group tents, databases, and a policy that one person per tent must be nominated to collect the food for everyone in that tent (I18, 2020). In addition to the division of data by spatial units, barriers such as fences were used to protect volunteers in the cramped conditions. These fences were also part of the techniques of strategic and temporary withdrawal that were used to restore order during the distribution (I3, 2018; I18, 2020).

Although this delegation of responsibility for food provision helped reduce the issue of undersupply, the NGOs were distributing the same low-quality food from the same caterers that were supplying the state food lines. As a result, the asylum seekers became physically weak due to the poor-quality food. This was described very emphatically by one interviewee:

And food … in the Moria camp, it's very, very, very bad food. … There is some, some meat, that gives people … very bad abdominal pain. And no energy, nothing, and when the people, they are new here, in 1 month, 2 months, they feel that they cannot move like they could when they were in Turkey [sic], Iran, or Afghanistan. (I9, 2019)

The asylum seekers responded to the lack of food supplies by organizing protests and obstructing supply routes – their own spatialized techniques (I1, 2018). Nevertheless, their primary means of obtaining food involved individual or collective efforts through which they procured food from outside the camp and set up their own communal cooking infrastructure (I10, 2019; I11, 2019). However, their cooking practices sometimes led to extensive fires in and around the camp and caused even more injuries and deaths. In response, the camp's management attempted to ban independent cooking. However, they lacked the necessary control and resources to enforce such a measure. Furthermore, according to one interviewee, the ban on cooking was immediately lifted when the camp was in quarantine because of the COVID-19 pandemic in an attempt to prevent both deaths and riots resulting from food scarcity (I17, 2020).

The undersupply of food and other goods, as well as inadequate accommodation and conflict control (see the following sections), led to life-threatening conditions in the camp, as well as infections and injuries among the asylum seekers. However, those affected had to be cared for under the same poor conditions and shortages. The office of the Health Ministry only conducted vulnerability assessments. They did not provide any medical care (I11, 2019). Furthermore, in order to avoid pressure from asylum seekers, the office was located within the RIC Area, which was fenced and to which entrance was regulated by techniques of identification, access control, and arbitrary enforcement by the police force (I9, 2019; B1, 2019).

As there was effectively no state health care in the camp, medical NGOs provided basic care. To do this, they also retreated behind fences and communicated with asylum seekers through these barriers when determining whom they could treat and whom they must prioritize (B5, 2019). These triage techniques, which were necessary given their limited time and resources, enabled NGO employees to avoid pressure from asylum seekers and minimize potential conflict (I6, 2018; I10, 2019). Another way that asylum seekers sought to maintain a basic level of health was by independently seeking medical care from nearby NGOs, doctors, and hospitals on the island. However, the NGOs outside the camps also faced high workloads and had to prioritize patients (I10, 2019), and asylum seekers only had limited access to hospitals. This limitation arose because of language barriers, hospital overload, and discrimination, issues that were sometimes compounded by the restriction of the asylum seekers' mobility (I1, 2018; I15, 2019). Above all, it was the decreasing financial support and restricted access to health insurance that made it difficult for asylum seekers to care for their health outside the camp (ekathimerini, 2024b: n.p.).

4.2 Technologies of housing

The accommodation situation of the asylum seekers on Lesvos was also affected by the severe overcrowding in the camp. Once the authorities had registered the asylum seekers, the NGOs used their databases to find and allocate them accommodation. The databases were constantly being updated and changed in line with spatialized power techniques, such as control walks, and with documentation of free or illegally occupied accommodation and restructuring and reorganization of containers and tents (B2, 2019). As was observed several times (B2, 2019; B3, 2019), if an asylum seeker refused to move to their allocated accommodation or independently relocated to another place, Eurorelief, in particular, used various techniques to pressure them into returning to their allocated place. These techniques included de-registration, intrusively persistent communication, and, in exceptional cases, police force. In many other cases, asylum seekers came to Eurorelief's central information point to demand a move, and usually, any conflicts arising from such demands were waited out. Volunteers would retreat to the NGO's nearby containers, which were situated behind barriers such as desks and gates, and either pretend to talk to supervisors or simply stay there until the asylum seeker gave up (I9, 2019). The NGO's use of such techniques prevented asylum seekers from improving their housing situation within the camp, primarily under the rationale of maximizing the camp's capacity. However, the cramped housing conditions these policies created often led to rapid disease spread and, sometimes, violent conflict (I1, 2018). Asylum seekers were only required/permitted to build their own housing when severe overcrowding occurred (I9, 2019). These poor accommodation conditions also left asylum seekers vulnerable to adverse weather conditions. In winter, many suffered from frostbite and other cold-related illnesses, as well as burns, smoke inhalation, and poisoning caused by attempts to heat shelters with open fires or gas. In contrast, during the summer, the high temperatures inside the tents led to dehydration that resulted in weakness and fatalities among asylum seekers (ekathimerini, 2024a: n.p.).

In addition to this general accommodation situation, which mainly affected single men and, at times of extreme overcrowding, families, other spaces and networks were established to accommodate the groups identified as particularly vulnerable, such as single women, victims of torture, and unaccompanied minors. Within Moria, access to the RIC Area, where those with vulnerable statuses were housed, was regulated by a controlled gate, and supplies, including meals, were distributed separately to avoid subjecting these groups to the general supply conditions (I14, 2019).

Other accommodation options included the municipal camp, Kara Tepe, which primarily accommodated people and families with special needs (I8 2018), rented flats (UNHCR, 2024: n.p.), and a camp run by the NGO Lesvos Solidarity (Lesvos Solidarity, 2024: n.p.). However, these other shelters were not easily accessible to most people, as they were specifically reserved for the most vulnerable groups and had very limited capacity. As a result, their presence had a minimal effect in terms of alleviating the life-threatening accommodation situation in Moria.

4.3 Technologies of security

The inadequate care and poor accommodation consistently produced conflict within the camp, including extensive fights, some of which resulted in deaths (I9, 2019). The camp administration and police authorities used various strategies to produce different degrees of security depending on the space and groups affected by the issues. To meet these goals, they also involved groups of asylum seekers in the creation of a precarious yet stable security situation. Thus, central locations within the camp, including the area for particularly vulnerable people, were protected by the police, and vulnerable groups were relocated, as explained above (I14, 2019). However, the general security situation for asylum seekers was quite precarious, as the police resources available were only enough to cover a limited area of Moria and Olive Grove during their occasional patrols. Thus, as techniques of control, they were only applied to a small part of the camp, and as a result, many asylum seekers felt unprotected by the Greek authorities (I7, 2018; I19, 2020). During more extensive fights among asylum seekers, security authorities seldom intervened promptly or did not intervene at all, and their inaction resulted in numerous injuries and, at times, fatalities:

Level three, all of them were Kurdish, all of them were Kurdish, and, eh, when the Syrians, they come together for fighting, the fighting starts at 8 p.m., and it's going on till morning. But … no police officer separated them. … There was just, I mean that there was a lot of police officers, but just they looked how the refugees, they kill each other. (I9, 2019)

Rather than implementing sufficient security measures, the police forces attempted to transfer the responsibility for ensuring the asylum seekers' safety onto the asylum seekers themselves, citing limited resources and the fact that the asylum seekers had a vested interest in having a secure environment as grounds for the decision. For instance, they used discursive techniques to encourage asylum seekers to protect themselves against other groups and to use their own security techniques to deal with incidents such as theft or violence. These strategies also involved asylum seekers turning delinquents over to the police (I3, 2018). In some cases, asylum seekers in unique positions, such as the community leaders of the respective groups, were used to identify individuals for prosecution. At such times, the community leaders also referred to their community's own interest in ensuring their safety (I2, 2018; I4, 2018).

However, whenever asylum seekers directed violence or their protests towards authorities, infrastructure, or institutional practices, the police did respond and, in most cases, they responded with violent, repressive techniques. The asylum seekers were, thus, exposed to life-threatening conditions in this way as well. In particular, after the fire at the camp in autumn 2020, a large number of police from the mainland were deployed to the camp, and a period of severe repression followed that was designed to force asylum seekers to move to the new camp (I18, 2020). This action directly contradicted the police force's claim that they had insufficient staff to properly monitor the camp (I4, 2018). In addition, during the time that Moria was in operation, there were numerous cases of police brutality and oppression. For example, police forces met protests about asylum procedures and supply conditions with physical violence. In particular, tear gas was used on a large portion of the camp population, including on people who were not involved in the protest (I4, 2018; I19, 2020). When responding to protests, authorities also applied power techniques such as random checks of accommodation and residence permits, sometimes making arbitrary arrests in the process (Legal Centre Lesvos, 2018: n.p.). The conditions in the camp's prison, which held people with a low recognition rate and people who had been found guilty of disorderly behaviour without a court hearing, repeatedly led to disease outbreaks (I13, 2019), exposed inmates to life-threatening conditions, and triggered prisoner suicides – especially among those in solitary confinement (Legal Centre Lesvos, 2020: n.p.). Overall, it can be said conclusively that a lack of adequate protection for asylum seekers produced life-threatening conditions in the camp and that these conditions were exacerbated by the arbitrary violence and repression inflicted by state forces. In many cases, deaths were only prevented by last-minute police intervention or by the self-organized security techniques initiated by the asylum seekers.

4.4 Modes of governing and scalar conflicts

Several rationales and modes of governing have been identified on different scalar levels and between actors that sometimes corresponded and sometimes conflicted with each other yet, either way, helped to stabilize the technologies that kept asylum seekers on the brink of death. First, the EU implemented the hotspot mechanism as an attempt to re-stabilize the Schengen and Dublin regimes at a time when the EU states were working against an even distribution mechanism throughout the EU (Lutz et al., 2020). Through new regulations, deals such as the EU–Türkiye deal, and the funding of new camps, the EU institutions sought to keep the government of asylum-related migration contained to the region's periphery (Mouzourakis, 2019). Despite attempts to maintain humanitarian discourses, rationales for reducing migration and “pull factors” that hardened the living conditions for unwanted asylum seekers became increasingly dominant (Eliassen, 2010: n.p.).

On the national level, Greece also tried to keep the management of asylum seekers on the country's periphery by regulating the provision of material and personal resources (I4, 2018; I18, 2020).1 In addition to tightening the migration laws, especially those relating to the hotspot camps, the state did not provide enough money or personal resources to run the camps properly. There were two main reasons for this approach. First, the state had adopted the rationales of reducing pull factors (Papadatos-Anagostopoulos, 2010: n.p.). Second, it was attempting to pressure the EU into providing more funding and to force other EU countries to accept refugees despite the existing regulations (see Skleparis, 2017). At the same time, special laws were implemented for vulnerable asylum seekers that often led to their being relocated within Lesvos or transferred to the mainland by lifting the geographic restrictions placed on them. This helped maintain humanitarian discourses on the national level (Mouzourakis, 2019).

Two local institutions, the municipality of Lesvos and the camp management of Moria, were required to implement the hotspot mechanism at the local level with very few resources. Both state and EU institutions were involved in managing the mobility and registration of the asylum seekers, key elements of the central technologies (the restriction of mobility and restricted access to asylum processes) that ensured the basic functions of the camp. However, other technologies, such as supply, housing, and security, were characterized by the strategic withdrawal of these same state institutions and the active endangerment of asylum seekers. In turn, this necessitated the incorporation of NGOs into the government of the camp. These NGOs were primarily guided by humanitarian discourses combined with rationales of effectiveness and balancing the needs and vulnerabilities of asylum seekers (I14, 2019; I6, 2018). The asylum seekers themselves were also incorporated into these technologies through their vital contributions to the self-organized provision of food and by implementing techniques of security through their cooperation with the authorities. In order to ensure the basic functioning of the camp and the survival of its residents, albeit on the brink of death, the camp's management facilitated certain strategic practices in response to the asylum seekers' demands, such as overlooking the self-organized provision of food and the self-built huts mentioned above. Furthermore, people identified as especially vulnerable were, depending on the resources available, treated differently again and given special services such as food and housing in facilities other than Moria. Nevertheless, in addition to fostering harsh living conditions to deter asylum seekers from coming to Greece, the municipality used the poor conditions to pressure the national authorities to transfer asylum seekers to the mainland in order to help relieve the overcrowding and maintain the operation of the camp:

I mean, there was a huge international outcry, and everybody said Lesvos is the worst place in the world, and this cannot exist, and the authorities used that to get people transferred. So, they apply to the ministry, and then of course the ministry gets pressure from the EU, like this is starting to look really bad, so they opened up new camps on the mainland, without any facilities, no access to healthcare, no access to anything. (I10, 2019)

This illustrates that it was not only actors on higher scalar levels that implemented their own rationales but that scalar conflicts also evolved from the bottom up.

This article has identified how several power technologies produced the localization of asylum seekers in Moria on the brink of death. In order to answer this question, I have analysed my ethnographic research against the backdrop of the post-structuralist concept of technology and expanded it using relational–spatial theories. This framework has allowed me to identify individual power techniques, their supporting relationships, and the resulting superordinate power effects that constitute the power technologies deployed at Moria. Thus, the framework contributes to the critical geographical analysis of encampment and biopolitics in the field of asylum, as it grasps the everyday and often-invisible power techniques and their socio-spatial relations. This framework has also facilitated the examination of the small-scale and everyday negotiation and stabilization of the modes of governance used in the camp, as well as their different scalar contexts of migration and asylum politics.

On Lesvos, the technology for restricting the mobility of asylum seekers was implemented to control their mobility. In addition, access to asylum processes was heavily regulated, primarily through the technology of socio-spatial access regulation. Both of these main technologies contributed to the massive overcrowding in the camp. In addition, the state's technology of care and accommodation was characterized by strategic under-provision and non-regulation. Together, these four technologies developed in Moria generated many non-fatal yet life-threatening conditions in the form of a lack of adequate care and conflict over scarce resources within the affected groups. In addition, the fifth technology of security production ensured that the asylum seekers were not adequately protected from the violence and insecurity that emerged in these conditions, with the result that, at times, people were exposed to not only violence but also police violence.

However, NGOs were involved in implementing strategies to alleviate these harsh conditions, and the majority of asylum seekers in Moria survived. The NGOs organized significantly more power techniques related to essential services like food, medical care, and accommodation in an attempt to meet these needs despite the overcrowded conditions and scarce resources. While they also used techniques of strategic withdrawal into secured spaces that asylum seekers could not enter in order to discipline them or diffuse difficult situations, they organized care as effectively as possible through the material frameworks of distribution and documentation, that is, by checking people's entitlements and prioritizing those in greater need of treatment or support. Techniques of control, knowledge production, and violence were also used in order to accommodate as many people in the camp as possible in these tense conditions.

The asylum seekers themselves were also involved in the camp's government and governing technologies, as they took an interest in their own survival and endeavoured to contribute and improve their living conditions. They were given limited opportunities to ensure their safety through techniques related to discipline, location, and cooperation with authorities (for example, by handing other asylum seekers over to police forces). In order to enable asylum seekers to provide for themselves, the camp administration strategically adapted the range of permitted practices for food supply and the building of accommodation.

The effects of these technologies were, in turn, strategically incorporated into migration management policies. According to some interviewees, the physical and psychological weakening of asylum seekers through care and housing technologies, repressive and life-threatening security policies, and the strategic control of their ability to move around the island/country while under the provision of care ensured that those affected were less likely to protest for their rights. Furthermore, the sub-standard living conditions prevalent in the Moria refugee camp led to two additional significant impacts. As stated, the EU and the Greek state had attempted to reduce the pull factors enticing asylum seekers to Lesvos by producing hostile living conditions. While the effectiveness of this strategy can be questioned based on other empirical refutations of the theory (see Garelli and Tazzioli, 2021) and the consistently high number of arrivals throughout the period studied, another effect was clearly observable: the inhospitable conditions did prompt both the EU and the Greek state to arrange transfers to the mainland. Another effect, using different techniques to address various vulnerabilities, allowed Greece and the EU to maintain human rights discourse despite the sub-par living conditions being endured by most of the camp's residents.

In conclusion, this article highlights the importance of conducting a local analysis of migration governance. With this analysis, I have demonstrated a framework that helps identify the overarching effects of the strategic power technologies based on the interplay between the various actors and socio-spatial power techniques in use. With regard to the specific areas of biopolitics and necropolitics in camp studies, this analysis shows that it is not only necropolitics and the production of the “living dead”, which involve harsh exclusion and the suspension of basic rights, that result in violent circumstances. There is a complex interplay of different power techniques and technologies involved in producing the life-threatening conditions that place refugees on the brink of death, while keeping the majority of refugees alive. Indeed, many actors, including NGOs and refugees, and their various strategies had to be taken into account and strategically influenced. In this context, the agency and survival strategies of refugees that are often emphasized within camp studies were used in order to stabilize the various technologies. In addition, the state was shown to be actively inactive in relation to the provision of basic goods when it used socio-spatial techniques to withdraw from services and accessibility, all the while actively constructing the main technologies used in the camp, in particular, the restriction of asylum seekers' mobility and access to asylum processes: the foundational methods that ensured that the asylum seekers at the camp continued to suffer on the brink of death. Thus, instead of only talking about the abandonment of refugees, we need to discuss a continuum with strategic control at one end and abandonment at the other.

With the election of the conservative party, Nea Dimokratia (which occurred after my research period came to a close), the living conditions in Moria and in the ad hoc camp, Kara Tepe, became increasingly precarious after a large fire on Moria, and even more deaths have occurred that are related to the rationale of reducing the numbers of asylum seekers. In the first year after its election, Nea Dimokratia cut back most of the mechanisms that eased the situation for asylum seekers and, in particular, those identified as vulnerable. In addition to enforcing the geographical restriction of vulnerable people, the government cut back the personal payments to asylum seekers, their health and social insurance, and the housing programme for vulnerable people (Statewatch.org, 2024: n.p.). These policies, combined with the stricter regulations on NGOs and attempts to keep NGOs out of the ad hoc camp, led to increasingly precarious living conditions for all asylum seekers on the Aegean Islands and the Greek mainland. The reorganization of the closed camps on the Aegean Islands, the complete restriction of the mobility of asylum seekers, and the lack of access to care and legal support (Bordermonitoring Aegean, 2024: n.p.) will presumably worsen the situation. Indeed, overall, the increasing push-back practices since 2020 and the criminalization of asylum seekers crossing the Aegean, which has led to numerous deaths (see mare liberum, 2021), illustrate the constant shift toward more fatal necropolitics in camps and, in particular, in the upstream technologies used to govern the camps. Thus, future research is needed to examine whether the location of asylum seekers on the brink of death can still be stabilized through the camp's power technologies or whether this is no longer the case, given the consistent shift toward more necropolitical technologies.

| I1 | Interview with asylum seeker next to RIC Lesvos on 5 August 2018. |

| I2 | Interview with asylum seeker at Olive Grove on 7 August 2018. |

| I3 | Interview with asylum seeker at Olive Grove on 13 August 2018. |

| I4 | Interview with police officer at RIC Lesvos on 11 August 2018. |

| I5 | Interview with asylum seeker at Olive Grove on 10 August 2018. |

| I6 | Interview with NGO staff at a café next to RIC Lesvos on 13 August 2018. |

| I7 | Interview with NGO staff at a café on 1 August 2018. |

| I8 | Interview with camp management at Kara Tepe on 8 August 2018. |

| I9 | Interview with asylum seeker next to RIC Lesvos on 23 March 2019. |

| I10 | Interview with NGO worker at a Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) children's clinic on 13 March 2019. |

| I11 | Interview with asylum seeker at a café in March 2019. |

| I12 | Interview with asylum seeker at a café next to RIC Lesvos on 18 September 2019. |

| I13 | Interview with two asylum seekers at a café on 8 September 2019. |

| I14 | Interview with NGO staff at a café in March 2019. |

| I15 | Interview with asylum seeker at Olive Grove on 14 April 2019. |

| I16 | Interview with asylum seeker at a café next to RIC Lesvos in April 2019. |

| I17 | Interview with asylum seeker by telephone on 20 March 2020. |

| I18 | Interview with asylum seeker at a bar next to Mavrovouni camp on 24 October 2020. |

| I19 | Interview with asylum seeker at a bar next to Mavrovouni camp on 27 October 2020. |

| B1 | Observation at RIC Lesvos on 15 March 2019. |

| B2 | Observation at RIC Lesvos on 18 March 2019. |

| B3 | Observation at RIC Lesvos on 20 March 2019. |

| B4 | Observation at RIC Lesvos on 21 March 2019. |

| B5 | Observation at RIC Lesvos on 29 March 2019. |

The research data is not available to protect interview partners in the sensitive field of refugee camps.

The author has declared that there are no competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

I would like to thank all my interview partners, who provided me such deep insights into their stories and views on the living conditions on Lesvos. Also, I want to thank the editors of the special issues for the helpful feedback during the writing process.

This paper was edited by Lucas Pohl and reviewed by two anonymous referees. The editorial decision was agreed between both guest editors, Lucas Pohl and Jan Hutta.

Aegean Boat Report: Annual Report 2020, https://aegeanboatreport.com/annual-reports/ (last access: 24 July 2025), 2021.

Allen, J.: Lost geographies of power, 1. publ., Blackwell, Malden, Massachusetts, https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470773321, 2003.

Becker, S. and Aiello, B.: The continuum of complicity: “Studying up”/studying power as a feminist, anti-racist, or social justice venture, Womens Stud. Int. Forum, 38, 63–74, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2013.02.004, 2013.

Bordermonitoring Aegean: The Dystopia in form of a camp – The “Closed Controlled Access Centre of Samos”: https://dm-aegean.bordermonitoring.eu/2022/03/24/the-dystopia-in-form-of-a-camp-the-closed-controlled-access (last access: 25 April 2024), 2024.

Breuckmann, T.: Institution Lager. Theorien, globale Fallstudien und Komparabilität, in: Die Institution des Lagers und seine Ordnungen, edited by: Bochmann, A. and Fischer von Weikersthal, F., Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, 89–109, ISBN 9783593516851, 2023.

Breuckmann, T: Die Regierung von Migration in Lagern. Geographien der Macht am Beispiel Lesvos, Westfälisches Dampfboot, Münster, ISBN 9783896910936, 2024.

Bussolini, J.: What is a Dispositive?, Foucault Stud., 10, 85–107, https://doi.org/10.22439/fs.v0i10.3120, 2010.

Charmaz, K.: Constructing grounded theory, 2nd Edn., SAGE, Los Angeles, California, 388 pp., ISBN 978-1-5264-2660-4, 2014.

Clarke, A. E., Friese, C., and Washburn, R.: Situational analysis: grounded theory after the interpretive turn, 2nd Edn., SAGE, Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington, D.C., Melbourne, 426 pp., https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412985833, 2018.

Clark-Kazak, C.: Ethical Considerations: Research with People in Situations of Forced Migration, Refuge, 33, 11–17, https://doi.org/10.7202/1043059ar, 2017.

Córdova Morales, E.: The black holes of Lesbos: life and death at Moria camp: Border violence, asylum, and racisms at the edge of postcolonial Europe, Intersections, 7, 73–87, https://doi.org/10.17356/ieejsp.v7i2.895, 2021.

Davies, T., Isakjee, A., and Dhesi, S.: Violent Inaction: The Necropolitical Experience of Refugees in Europe, Antipode, 49, 1263–1284, https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12325, 2017.

Dean, M.: Putting the technological into government, Hist. Hum. Sci., 9, 47–68, https://doi.org/10.1177/095269519600900303, 1996.

Deppermann, A.: Das Forschungsinterview als soziale Interaktionspraxis, in: Qualitative Forschung, edited by: Mey, G. and Mruck, K., Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden, 133–149, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-05538-7_8, 2014.

ekathimerini: Seeking justice for Moria death, https://www.ekathimerini.com/in-depth/special-report/235269/seeking-justice-for-moria-death (last access: 24 April 2024), 2024a.

ekathimerini: Greece to grant provisional social security number to asylum seekers, https://www.ekathimerini.com/news/249145/greece-to-grant-provisional-social-security-number-to-asylum (last access: 24 April 2024), 2024b.

Eliassen, I.: The EU asylum policy of deterrence is inhumane – and does not work, https://www.investigate-europe.eu/en/posts/eu-asylum-policy-deterrence (last access: 16 May 2025), 2010.

Felder, M., Minca, C., and Ong, C. E.: Governing refugee space: the quasi-carceral regime of Amsterdam's Lloyd Hotel, a German-Jewish refugee camp in the prelude to World War II, Geogr. Helv., 69, 365–375, https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-69-365-2014, 2014.

Feldman, I.: What is a camp? Legitimate refugee lives in spaces of long-term displacement, Geoforum, 66, 244–252, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.11.014, 2015.

Foucault, M.: Das Spiel des Michel Foucault, in: Schriften in vier Bänden. Dits et Ecrits. Band III. 1976–1979, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main, 391–429, ISBN 978-3-518-58371-5, 2003.

Foucault, M. and Macey, D.: Society must be defended: lectures at the Collège de France, 1975–76, edited by: Bertani, M., Picador, New York, 310 pp., ISBN 9780312422660, 2003.

Garelli, G. and Tazzioli, M.: Migration and `pull factor' traps, Migr. Stud., 9, 383–399, https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnaa027, 2021.

Greek Council for Refugees: Country Report: Greece. 2019 update, European Council on Refugees and Exile, Athens, https://asylumineurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/report-download_aida_gr_2019update.pdf (last access: 25 July 2025), 2020.

Hänsel, V.: Gefangene des Deals: die Erosion des europäischen Asylsystems auf der griechischen Hotspot-Insel Lesbos, bordermonitoring.eu e.V., München, 151 pp., ISBN 978-3-947870-01-1, 2019.

Hernàndez, J.: Greece Struggles to Balance Competing Migration Demands, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/greece-struggles-balance-competing-migration-demands (last access: 28 March 2024), 2020.

Hess, S., Kasparek, B., Kron, S., Rodatz, M., Schwertl, M., and Sontowski, S.: Der lange Sommer der Migration. Krise, Rekonstitution und ungewisse Zukunft des europäischen Grenzregimes, in: Der lange Sommer der Migration, edited by: Hess, S., Kasparek, B., Kron, S., Rodatz, M., Schwertl, M., and Sontowski, S., Assoziation A, Berlin, Hamburg, 6–24, ISBN 978-3-86241-453-6, 2017.

Hoffmann, S.: Wen schützen Flüchtlingslager? “Care and Control” im jordanischen Lager Azraq, Peripher. – Polit. Ökon. Kult., 35, 281–302, https://doi.org/10.3224/peripherie.v35i138-139.24300, 2015.

Kuster, B. and Tsianos, V.: Hotspot Lesbos, Heinrich Böll-Stiftung, Berlin, https://www.boell.de/sites/default/files/160802_e-paper_kuster_tsianos_hotspotlesbos_v103.pdf (last access: 25 July 2025), 2016.

Legal Centre Lesvos: The case of the Moria 35: A 15-Month Timeline of Injustice and Impunity, https://legalcentrelesvos.org/2018/11/29/the-case-of-the-moria-35-a-15-month-timeline-of-injustice (last access: 25 July 2025), 2018.

Legal Centre Lesvos: Call for Accountability: Apparent Suicide in Moria Detention Centre Followed Failure By Greek State To Provide Obligated Care, https://legalcentrelesvos.org/2020/01/19/call-for-accountability-apparent-suicide-in-moria-detention (last access: 25 July 2025), 2020.

Lessenich, S.: Soziale Subjektivität. Die neue Regierung der Gesellschaft, Mittelweg, 36, 80–93, 2003.

Lesvos Solidarity: About Pikpa Camp, https://www.lesvossolidarity.org/en/who-we-are/history/pikpa-camp (last access: 24 April 2024), 2024.

Lutz, P., Kaufmann, D., and Stünzi, A.: Humanitarian Protection as a European Public Good: The Strategic Role of States and Refugees, JCMS J. Common Mark. Stud., 58, 757–775, https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12974, 2020.

Manderscheid, K.: Automobilität als raumkonstituierendes Dispositiv der Moderne, in: Die Ordnung der Räume. Geographische Forschung im Anschluss an Michel Foucault, edited by: Michel, B. and Füller, H., Westfälisches Dampfboot, Münster, 145–178, ISBN 978-3896919175, 2012.

mare liberum: Pushback Report 2021, mare liberum, Berlin, https://www.borderline-europe.de/sites/default/files/background/Pushback Report 2021 German.pdf (last access: 25 July 2025), 2021.

mare liberum: Moria 2.0 – The Reproduction of Inhumanity, https://mare-liberum.org/en/moria-2-0-the-reproduction-of-inhumanity/ (last access: 24 April 2024), 2024.

Martin, D., Minca, C., and Katz, I.: Rethinking the camp: On spatial technologies of power and resistance, Prog. Hum. Geogr., 44, 743–768, https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519856702, 2020.

Massey, D.: Politics and Space/Time, New Left Rev., 196, 65–84, 1992.

Mavelli, L.: Governing populations through the humanitarian government of refugees: Biopolitical care and racism in the European refugee crisis, Rev. Int. Stud., 43, 809–832, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210517000110, 2017.

Mbembe, A.: Necropolitics, Publ. Cult., 15, 11–40, 2003.

Mbembe, A.: Necropolitics, Duke University Press, Durham, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478007227, 2019.

Mouzourakis, M.: The Role of EASO Operations in National Asylum Systems, European Council on Refugees and Exile, Athens, https://ecre.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/EASO-Operations_Report.pdf (last access: 25 July 2025), 2019.

Murdoch, J.: Post-structuralist geography: a guide to relational space, SAGE, London, Thousand Oaks, California, 220 pp., ISBN 0 7619 7423 7, 2006.

O'Donnell, S.: Living Death at the Intersection of Necropower and Disciplinary Power: A Qualitative Exploration of Racialised and Detained Groups in Australia, Crit. Criminol., 30, 285–304, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10612-022-09623-2, 2022.

Oesch, L.: The refugee camp as a space of multiple ambiguities and subjectivities, Polit. Geogr., 60, 110–120, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.05.004, 2017.

Papadatos-Anagostopoulos, D.: COVID-19 (also) in Moria: The deficient handling of the pandemic as an attempt to instrumentalize refugees, Thessaloniki, https://gr.boell.org/en/2020/09/22/o-covid-19-kai-sti-moria-i-elleimmatiki-antimetopisi-tis (last access: 25 July 2025), 2010.

Pott, A.: Migrationsregime und ihre Räume, in: Was ist ein Migrationsregime? What Is a Migration Regime?, edited by: Pott, A., Rass, C., and Wolff, F., Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden, 107–135, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-20532-4_5, 2018.

Salmenkari, T. and Aldawoodi, S.: Papers of the Paperless: Governmentality, Technologies of Freedom, and the Production of Asylum-Seeker Identities, Int. Migr. Rev., 58, 909–935, https://doi.org/10.1177/01979183231154502, 2024.

Skleparis, D.: The Greek response to the migration challenge: 2015–2017, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, Athens, https://www.kas.de/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=9ca070c8-b546-01ac-e85a-df93ea2e5297&groupId=252038 (last access: 25 July 2025), 2017.

Statewatch.org: Greece: The new hotspots and the prevention of “primary flows”: a human rights disaster, https://www.statewatch.org/analyses/2021/greece-the-new-hotspots-and-the-prevention-of-primary-flows (last access: 9 December 2024), 2024.

Tazzioli, M.: Governing refugees through disorientation: Fragmented knowledges and forced technological mediations, Rev. Int. Stud., 48, 425–440, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210522000079, 2022.

Themann, P.: “His dead body is in the water right now” – Death, survival and hypermobility along the balkan route, Geogr. Helv., submitted, 2025.

Tsoni, I.: `They Won't Let us Come, They Won't Let us Stay, They Won't Let us Leave'. Liminality in the Aegean Borderscape: The Case of Irregular Migrants, Volunteers and Locals on Lesvos, Hum. Geogr., 9, 35–46, https://doi.org/10.1177/194277861600900204, 2016.

UNHCR: Towards ESTIA II: UNHCR welcomes Greece's commitment to ensure the continuation of flagship reception programme for asylum-seekers, https://www.unhcr.org/gr/en/15985-towards-estia-ii-unhcr-welcomes-greeces-commitment (last access: 24 April 2024), 2024.

Wilson, B. K., Burnstan, A., Calderon, C., and Csordas, T. J.: “Letting die” by design: Asylum seekers' lived experience of postcolonial necropolitics, Soc. Sci. Med., 320, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115714, 2023.

Zena, E.: The Bio/Necropolitics of State (In)action in EU Refugee Policy: Analyzing Calais, E-Int. Relat., 1–7, https://www.e-ir.info/pdf/78634 (last access: 25 July 2025), 2019.

To date, it has not been possible to confirm the details of the funding provided for Moria's camp, in particular, whether it only received EU funding or whether it also received funding from the Greek state.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Governing populations through technologies

- Researching the Moria camp

- The technologies of the camp: placing asylum seekers on the brink of death in Moria

- Conclusion and recent developments

- Appendix A: Interviews

- Appendix B: Observations

- Data availability

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Governing populations through technologies

- Researching the Moria camp

- The technologies of the camp: placing asylum seekers on the brink of death in Moria

- Conclusion and recent developments

- Appendix A: Interviews

- Appendix B: Observations

- Data availability

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References