the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Temporary stay or new home? Exploring university students' perceptions of temporality and home

Caroline Kramer

Carmella Pfaffenbach

Leonie Wächter

Maya Willecke

While housing is often viewed as constant and permanent – both in everyday life and academic discourse – temporary living arrangements and mobility are increasingly common. Among university students, spatio-temporal patterns are particularly dynamic. Although parental homes often continue to play a significant role, new “homes” are frequently established in shared flats or apartments within university cities. However, these arrangements are often temporary, lasting only until the completion of students' studies. Students' perceptions of the temporality of their living arrangements during their studies results in complex relationships between spatial attachments – such as rootedness and spatial identity – and mobility. To contribute to this area of research, we conducted a study in the German university cities of Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig. Employing a mixed-methods approach, we combined a largely standardised questionnaire with semi-structured interviews. This methodology enabled us to generate a substantial dataset comprising both quantitative and qualitative data, yielding valid results. In this paper, we examine the extent to which students who relocate to university cities perceive their place of study as either temporary or permanent. Furthermore, we explore how these living arrangements impact their sense of place attachment, belonging and perception of home. By evaluating students' perceptions of their temporary living arrangements, we aim to highlight the significance of the temporal dimension in shaping their feelings of belonging. Our findings reveal that students' perceptions of temporality significantly influence their emotional spatial attachments to university cities. Focusing on students who have relocated to university cities provides valuable insights, as they represent a considerable portion of the population, and many express intentions to become permanent residents.

- Article

(2171 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Every year, thousands of new students begin their studies in German university cities, relocating to these urban centres during a relatively fixed timeframe, particularly for Bachelor's and, to some extent, Master's programmes, with the potential to extend their stay as young professionals. Students must navigate tight housing markets in these cities in search of accommodation; therefore, some may elect to continue living with their parents and commute to university until they find a place to live in the city. This paper explores the experiences of these new student residents in German university cities, focusing on their aspirations and opportunities to create a sense of home during their studies and beyond.

The higher education landscape in Germany has undergone a significant change over the past two decades, characterised by a substantial increase in the number of university students (Glatter et al., 2014; Destatis, 2022). This growth can be attributed to several factors, including a higher proportion of high school graduates and university entrants and a rising influx of international students (Glatter et al., 2014). The majority of students in Germany live in rented accommodation (59 %), while smaller percentages live in owner-occupied housing, typically owned by their parents (21 %), or in student dormitories (17.5 %). Rental costs vary significantly depending on the type of housing, with average monthly rents of approximately EUR 260 for student dormitories and EUR 490 in the private rental market (Kroher et al., 2023). The average monthly expenditure for students in Germany is around EUR 1000, and rent typically constitutes their largest expense. Students can apply for government financial support through BAföG,1 with the average monthly assistance amounting to EUR 611. Without parental support or BAföG, many students rely on part-time employment, with 63 % working alongside their studies, averaging about 15 h per week (Kroher et al., 2023). German universities do not impose general tuition fees; instead, students are required to pay a semester contribution that covers various services, including student union membership and public transportation passes.

The most recent study on the mobility of German students indicates that two-thirds establish their own households at the beginning of their studies, 12 % do so later, and only 18 % continue living at home with their parents for the duration of their studies (Infas, 2015). The tendency to continue living at home is associated with proximity to the university city; among those who relocate, 55 % choose institutions located less than 100 km from their hometown, 29 % selected universities between 100 and 300 km away, and only 15 % attended universities more than 300 km from home (Infas, 2015). This pattern suggests that students prefer convenient distances to their families' residences, facilitating weekend visits to parents and friends. After completing their studies, 85 % of German students assume that they will (very or rather likely) move to another region of Germany to start their career (Statista GmbH, 2022). Consequently, taking their relocation intentions into account, many students could be regarded as temporary residents of their university cities – at least from an external perspective. Nevertheless, the question remains open and is worth investigating as to whether they themselves perceive their living arrangements in their university cities as temporary.

Given that, for the majority of students, the university city represents a new environment where they begin to live independently, it raises important questions about the significance of this place and the extent to which they feel at home there, despite often viewing their stay as temporary. Conversely, it is essential to consider students' impact on these university cities during their temporary residence, especially since they constitute between 10 % and 30 % of the total population in these towns (Glatter et al., 2014). This demographic creates what has been described as a “standing wave”, characterised by a consistently high number of residents coupled with significant fluctuation (Kramer, 2019).

In a study conducted in the German university cities of Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig, we explored the significance of these cities for students who have relocated there in recent years. To achieve this, we employed a mixed-methods approach comprising a quantitative questionnaire survey with 673 respondents and 50 qualitative interviews, allowing us to explore this phenomenon from two methodological perspectives. This paper examines the extent to which university students perceive their place of study as temporary or permanent, as well as the implications for their sense of home, belonging and place attachment. We begin by introducing the conceptual and theoretical framework surrounding temporalities and the temporary living arrangements of university students, alongside discussions of place attachment, belonging and the concept of home for those who have moved to these cities. Following the introduction of our mixed-methods approach, we will present our findings in relation to three key research questions. (1) Why and from where do students relocate to these university cities? (2) How do these students perceive the temporality of their living arrangements in these cities? The insights gained from these two questions will provide the context for the third question: (3) to what extent do students who have moved to these university cities develop emotional attachments to their new environments? We will conclude by discussing the implications of our findings and by summarising the key insights derived from our research.

2.1 The temporalities of students' living arrangements

Whereas earlier studies, such as those by Hägerstrand (1985) and Urry (1999), treated time and space as analytically connected yet distinct dimensions, more recent conceptualisations emphasise the dynamic, relational and processual nature of spatio-temporal relationships (Massey, 2005). This perspective reframes mobility and dwelling as interconnected processes that unfold across space and time, rather than opposing concepts. Within this framework, mobility is understood not merely as movement through space; it is shaped by formative place experiences, interpersonal relationships and broader structural conditions (Bailey et al., 2021). The concept of “fixities and flows” (Di Masso et al., 2019) enhances this perspective by demonstrating that mobility and place attachment are interdependent constructs within spatio-temporal dynamics rather than mutually exclusive or contradictory.

Recent geographic studies have explored how everyday practices, such as dwelling – traditionally viewed as spatially fixed – are influenced by temporal factors. Increased mobility has transformed travel and location practices into a new form of “geographicity”, defined as “the spatial embeddedness of human life” (Stock, 2014), blurring the boundaries between residing and relocating. In contemporary contexts, practices like dwelling are increasingly detached from a single, fixed location. Temporary stays and the rhythmic use of multiple places reflect a departure from the concept of “monotopicity”, which suggests a tie to a single place (Stock, 2014). Instead, individuals engage in “polytopicity”, the practice of creating and occupying several meaningful places (Stock, 2024). This shift contributes to an expanded understanding of dwelling, shaped by both symbolic and material practices.

For students, the period of study represents a distinct phase in their lives, characterised by a defined spatio-temporal framework. Typically, students pursue their university degrees at the location of their institution within a specific timeframe. Concurrently, they maintain connections to their hometowns, where family and friends reside. As a result, students become multi-local residents (Greinke, 2023), with a temporary presence in both their university cities and hometowns. This duality leads to significant differences in their everyday spatio-temporal practices (multi-locality) and duration of residence (temporality) compared to the general population.

The impact of students on their chosen neighbourhoods has been examined and critically labelled as “studentification” (Smith, 2005). The effects of this phenomenon can be particularly pronounced when daily life is influenced by the seasonality associated with the academic semester or when there is a high concentration of students in specific neighbourhoods. However, the influence of students on neighbourhoods tends to be less pronounced in Germany, as the structure of city districts is often more diverse compared to university cities in the UK (Kramer, 2019).

2.2 Concepts of place attachment, belonging and home

The existing literature presents various approaches to conceptualising emotional bonds and spatial attachments. In our study, we have selected the concepts of “place attachment” and “home” to investigate the emotional and spatial attachments formed by university students. Place attachment is defined as the emotional bond individuals develop with specific places (Altman and Low, 1992; Tuan, 1980). Unlike related concepts such as “sense of place” or “place identity”, place attachment offers a more process-oriented and multidimensional framework for understanding the formation of spatial bonds. Raymond et al. (2010) applied this concept in a quantitative empirical study, proposing a four-dimensional model of place attachment. This model includes (1) place identity, (2) place dependence (or functional rootedness) within a personal context, (3) social bonding (which includes attachment to a neighbourhood, feelings of belonging and familiarity) within a community context and (4) nature bonding (the connection to nature and environmental identity) within an environmental context. Given this differentiated perspective on the various dimensions of place attachment, we will employ a multi-dimensional framework to analyse the extent to which students who consider themselves temporary residents perceive their attachment to a university city (see Sect. 4.3).

In our qualitative analysis, we utilise the concept of home, as it offers a broad and multifaceted framework for understanding spatial and emotional attachment. Home can be seen as an even stronger and more intimate form of attachment than the place attachment, as Easthope (2004) also describes it as a “significant kind of place”. This concept operates on multiple scales and supports a dynamic, process-oriented perspective. The concept of home is inherently complex, incorporating spatial, social, psychological and emotional dimensions (Easthope, 2004). While the term “home” may suggest a singular physical location, it may be used to refer to multiple places that can exist both successively and simultaneously, spanning various spatial scales – from an individual's primary dwelling to broader regions and even a homeland (Boccagni and Kusenbach, 2020). Furthermore, the emotional experience of home can transcend specific locations and be grounded instead in ideas, values or language (Winther, 2009). The feeling of home is closely linked to spatial identity (Weichhart, 2019) and may be shaped by social interactions, emotional relationships, material objects and environments (Blunt and Dowling, 2022).

Contemporary literature increasingly recognises that home is not a static concept confined to a specific time and place; rather, it is continually reinvented across different locations (Cieraad, 2010). Therefore, the experience of home should be understood as a process (Dowling and Mee, 2007) that is continuously reconfigured through everyday practices. German scholars often differentiate between Heimat (place of origin) and Zuhause (current home), a distinction that does not have a direct equivalent in English: Heimat is understood biographically, linked to one's roots and past, serving as a retrospective imagination, while Zuhause is shaped by current life contexts and holds significance in the present (Nadler, 2013; Weichhart, 2019).

2.3 Current research on students' emotional spatial attachments

A systematic literature search on various concepts of emotional spatial attachment – using keywords such as “place identity”, “sense of community”, “place attachment”, “sense of belonging”, “home” and “student” – identified several publications in both German and English, published after 2010. This timeframe was selected for heuristic reasons to capture recent developments and to provide a robust foundation for interpretation. Quantitative studies have primarily addressed place attachment and place identity (Cicognani et al., 2011; Moghisi et al., 2015; Qingjiu and Maliki, 2013; Rioux et al., 2017; Scopelliti and Tiberio, 2010), while qualitative research has focused on the sense of belonging (Bettencourt, 2021; Dost and Mazzoli Smith, 2023; Holton and Finn, 2020; Pokorny et al., 2017) and the concept of home (Balloo et al., 2021; Cieraad, 2010; Landolt and Frey, 2020). The following sections will provide a detailed summary of these concepts, referencing the most relevant articles.

Previous research in mobility studies has demonstrated that place attachment and a sense of belonging are often associated with permanence in a specific location, with the assumption that the relationship with a place intensifies over time (Gustafson, 2001; Lewicka, 2010). Similarly, studies focusing on students have found that place attachment tends to strengthen with the duration of their studies and time spent in their university city (Moghisi et al., 2015; Kramer, 2019; Cicognani et al., 2011). This phenomenon is related to the fact that, as students' progress through their semesters, an increasing number spend their lecture-free periods in the university city, gradually making it the centre of their lives (Kramer, 2019; Rioux et al., 2017). International studies from the USA and Malaysia emphasise the importance of the campus in fostering bonds among students (Bettencourt, 2021; Qingjiu and Maliki, 2013). This phenomenon is partly due to the common practice in these countries of moving into campus accommodation during the early years of study.

In the UK, the debate surrounding studentification (Smith, 2005) has prompted several studies to examine students' attachments to university cities. These studies particularly differentiate between local and non-local students, revealing that their attachments and feelings of belonging to these cities, and to their hometowns, can differ significantly (Holton, 2015; Holton and Finn, 2020). As demonstrated in studies on mobility and multi-locality, students can develop attachments to multiple places (Hilti, 2013; Nadler, 2014; Stedman, 2006; Williams and Patten, 2006) as well as to the spaces in between (Holton and Finn, 2020). This phenomenon aligns with the concept of “polytopicity” proposed by Stock (2024).

Research that explicitly addresses home as a form of emotional spatial attachment has shown that university students are often aware of their temporary status and that they will only be residing in their university city for a limited time, with their next move already in mind. Consequently, many students are reluctant to form strong attachments to their current place of residence (Balloo et al., 2021). This awareness can lead to uncertainty regarding the concept of home – whether they have a home at all or regard multiple places as home (Balloo et al., 2021). Various studies have identified social networks, relationships and (social) interactions as crucial in fostering a sense of belonging among university students (Dost and Mazzoli Smith, 2023), leading to higher levels of place attachment (Moghisi et al., 2015).

In the German context, where relocating to another city for studies is common (Infas, 2015), aspects such as place attachment, belonging and home have received relatively little attention. Furthermore, there are currently no studies that investigate (1) the reasons why students choose a particular university city, (2) how students who have moved to these cities perceive the temporary nature of their living arrangements and (3) the extent to which they develop emotional spatial attachments to their university city. In this paper, we will examine these three aspects and support our findings with results from a mixed-methods study in two German university cities.

3.1 Research design

Our approach employed both qualitative and quantitative methods to ensure a comprehensive understanding of students' perceptions of temporality and their feelings of home. We used a standardised questionnaire that inquired about students' housing, work and study situations, as well as their emotional attachments to their city. To facilitate participation, we distributed flyers and posters featuring QR codes that provided online access to the survey in both English and German. This survey targeted all students, including those who relocated to the university city for their studies and those who had been living there prior to commencing their studies. This article will focus exclusively on the datasets of students who relocated to the university city.

Additionally, we conducted qualitative semi-structured interviews with students who had relocated to university cities. These interviews provided further insights into their decision-making processes, future aspirations and strategies for establishing a sense of home. Interviewees were approached directly on campus and through social networking sites.

Both datasets addressed the same core research questions. The quantitative data provided a broad statistical overview, while the qualitative data offered in-depth insights into individual experiences and perceptions. The alignment in the content across both datasets allowed us to relate and combine the respective results. Triangulating data from multiple sources contributes to our understanding of the phenomena under investigation and enhances the validity of the results.

3.2 Research area

With a population exceeding 750 000, Frankfurt am Main is the fifth largest city in Germany within a polycentric city region in western Germany. It is also the fifth largest university city, hosting over 70 000 students, making up 9.3 % of its residents. Frankfurt is home to more than 20 state and private universities, with Goethe University Frankfurt being the seventh largest in the country, enrolling over 41 000 students in the winter semester of 2023/2024 (Universität Frankfurt, 2024).

Leipzig, with a population of over 600 000, is the largest city in a monocentric city region in eastern Germany and ranks as the eighth largest city in the country. The city is home to over 40 000 students, accounting for 6.8 % of its residents. The majority of these students attend the University of Leipzig, which offers a diverse array of subjects across 14 faculties and more than 130 institutes (Universität Leipzig, 2024).

Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig differ structurally in several significant ways, and we anticipate that these differences will be reflected in our findings. While Frankfurt serves as a financial and service hub, hosting numerous globally operating companies (Stadt Frankfurt am Main, 2024), Leipzig is characterised by innovation-driven sectors, including research institutions, IT, media and the creative industries (Stadt Leipzig, 2025a). Both cities are grappling with a tight housing market due to rising rents; however, students in Leipzig still have access to affordable housing (Stadt Leipzig, 2025b). In contrast, Frankfurt faces a significantly more constrained supply of affordable apartments in the lower and mid-range price categories (Schipper, 2023).

By selecting two cities, we employ a comparative methodology that integrates both universalising and differentiating perspectives. The universalising perspective seeks to identify commonalities between the cities, enabling us to draw structural conclusions about students' temporary living arrangements. In contrast, the differentiating perspective highlights specific variations between the cities, uncovering diverse expressions of this phenomenon. This combination of approaches reveals underlying spatial processes and facilitates a nuanced assessment of their significance (Vogelpohl, 2013; Belina and Miggelbrink, 2010). In presenting our results, we will explicitly address differences when they arise while adopting a universalising perspective where appropriate.

3.3 Sample description

A total of 1010 students participated in the quantitative survey. Among the participants, 67 % (n=673) had moved to the university city in recent years. In terms of their temporary living arrangements, 7 % had lived there for less than 2 years, while only 8 % had resided in the university city for more than 6 years. Additionally, we conducted 50 qualitative interviews with 21 students in Frankfurt and 29 in Leipzig. The interviewed students had been living in their respective cities for periods ranging from 1 to 12 years; however, the 12-year duration is an exception, as it includes a student who worked for several years between their Bachelor's and Master's degree programmes. The students represent diverse fields of study, including social work, education, sociology, political science, geography, medicine, computer science, economics and law. Some students in Frankfurt also participate in dual degree programmes in collaboration with companies.

3.4 Evaluation methods

For the quantitative data, we aggregate several items from the questionnaire, particularly those related to students' living situations and feelings of belonging, into appropriate variables. Our survey design incorporates nominal categorical inquiries and multidimensional Likert scales, which are recognised as reliable tools for measuring opinions, perceptions and behaviours (Carifio and Perla, 2007). For this article, we use items from two different subject areas: firstly, statements about the students' living arrangement and, secondly, items to measure place attachment (Raymond et al., 2010). In analysing the data, we focused on the items related to place identity and social bonding, as these provided the most insightful findings. By applying these items, we can analyse differences in emotional attachment based on living situations using ordinal logistic regression (McCullagh, 1980).

The guidelines for the qualitative interviews were structured around four topics: reasons for selecting the residential location, type of housing, self-perception as temporary residents and feeling of home. The questions primarily targeted individual experiences, perceptions and emotions. We analysed the qualitative data using a coding process facilitated by MaxQDA software, which allowed us to identify significant patterns within the collected data (Flick, 2007). This analysis enables us to capture and understand the diversity of interviewees' individual experiences, opinions and perspectives.

Using a triangulation design (Plano Clark et al., 2008), we merged the results of the qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis in equal measure to facilitate comparison and interrelation. This mixed-method approach provides a rich and nuanced understanding of the underlying dynamics and implications of the phenomena under investigation, leading to a more comprehensive interpretation and explanation of the research findings.

4.1 Students' reasons for relocating to university cities and places of origin

An initial examination of the quantitative results revealed that, out of 1010 respondents, 67 % relocated to their university city in recent years. A closer analysis of migration rates for studying in Frankfurt and Leipzig identified variations. Specifically, 59 % of respondents in Frankfurt (n=307) moved to the city recently compared to 75 % in Leipzig (n=366). The average length of residence for students who moved to the university cities in our sample is 3.8 years, which aligns with the age structure (over 50 % between 20 and 24 years old) and study semesters (over 50 % are beyond the fourth semester). Interestingly, the average length of residence in Frankfurt (4.2 years) is higher than in Leipzig (3.4 years).

Based on the qualitative data, we identified specific reasons and motivations for moving to the respective cities, categorised as study-related, city-related or person-related. Almost all students interviewed in Frankfurt cited study-related reasons for their relocation, while the motivations expressed by students in Leipzig varied significantly.

Study-related reasons for relocating to Frankfurt include the university's respected reputation and the variety of degree programmes offered. For some, the opportunity to participate in a dual study programme in collaboration with a company was a decisive factor. Some interviewees highlighted their preference for a campus university where all facilities are in close proximity, complemented by green spaces that provide recreational and social opportunities. Other reasons for choosing to study in Frankfurt include advantages over other universities, such as more favourable application deadlines; the option to study with an “advanced technical college entrance qualification” (Fachhochschulreife); and, particularly for international students, the financial benefits available in Hessen, where tuition fees can be avoided, unlike in states such as Baden-Württemberg.

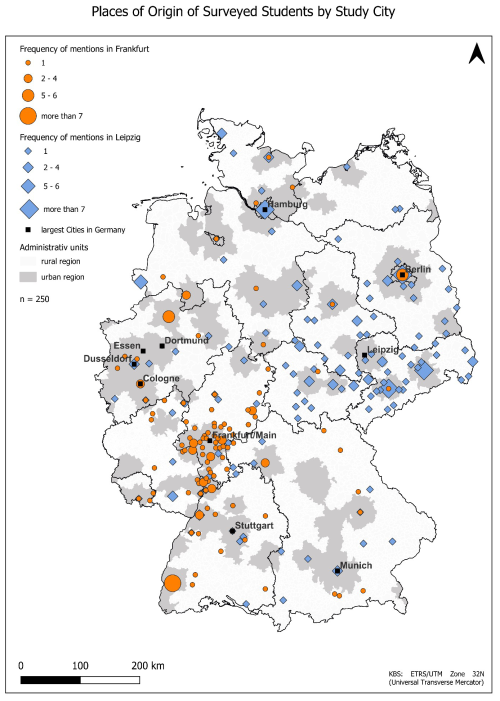

Person-related reasons include motivations linked to friends or family. Proximity to their parental homes and friends is particularly important for students in Frankfurt, as their families often reside nearby (see Fig. 2). As one student noted in an interview, the short distance between his residence in the city and his parent's home allows him to fulfil obligations in both locations: “It's very convenient that you can always go home when something comes up” (F14). In contrast, as many Leipzig students have families that live further away, these students often mention friends who already reside in the city as a motivating factor for relocating. Additionally, some students indicated that a partner who lives in the city or nearby, or wishes to move there, influenced their decision to relocate.

The city-related reasons mentioned in the interviews were quite diverse, encompassing factors such as the city's size; available facilities and amenities; and its overall image, “vibe”, and “hype”. In both university cities, students noted the city's size as a reason for their choice, describing it as having “exactly the right size”. They also mentioned its status as a major city with efficient public transport connections to various other locations. Frankfurt students highlighted the variety of banks and commercial enterprises as additional reasons for moving, particularly in relation to potential future job prospects. Conversely, Leipzig students emphasised the abundance of green spaces in the city and its surroundings, with one student remarking, “You walk ten minutes in one direction, and suddenly you're standing in the middle of the forest, and it's absolutely [beautiful]; wild trees and the river” (L4).

International students, in particular, appreciated the multicultural character of both cities. Additionally, affordability emerged as a significant factor. In Leipzig, low rents and a lower cost of living were decisive reasons for relocating, while in Frankfurt high rental costs were noted as a drawback. Interestingly, most students in Leipzig opt for shared flats primarily for social reasons, while students in Frankfurt choose shared accommodation primarily to reduce rental expenses.

Other city-related reasons are linked to the distinct images of each city. For Leipzig, the left-wing political scene and the LGBTQ* movement play a crucial role. In the interviews, students expressed a positive “gut feeling” (L2) and a specific “vibe” (L5, L2) associated with the city. One student remarked, “I think …. it's more of a vibe thing. It's really nice here, I've always felt really comfortable here and that hasn't changed to this day. It was a very strong good feeling” (L2). Another stated, “I fell in love with the vibe of the city straight away” (L5).

The analysis of the qualitative interviews revealed that students who moved to Frankfurt found the study programmes and campus more appealing than the city itself. Conversely, in Leipzig, students are drawn to the city's “vibe”, with the study programmes being of secondary interest.

Regarding the primary focus of this paper – the temporary nature of students' stays in university cities – the various reasons for initially relocating may impact their intentions to remain or move away after completing their studies. Specifically, study-related reasons for moving likely suggest that students will return to their hometowns or relocate elsewhere after graduation. In contrast, city-related or person-related reasons may indicate a greater likelihood of students staying in the university city beyond their studies. Unfortunately, we cannot quantify this potential influence, as the standardised survey did not capture reasons for moving. However, we can explore whether students perceive their stay in the university cities as temporary; this aspect will be discussed in Sect. 4.2, and the impact of this perception on their emotional spatial attachments will be addressed in Sect. 4.3.

Turning to the second question of this section – students' places of origin – the results again revealed clear structural differences between the two cities (see Fig. 1). It is evident that the families of students in Frankfurt predominantly reside within the polycentric Rhine–Main metropolitan region, which has a population of nearly 6 million (Region Frankfurt, 2024). In contrast, Leipzig's monocentric structure and smaller regional population result in fewer families living nearby. However, the families of many students in Leipzig still reside in the same federal state. Additionally, Leipzig exhibits a somewhat broader catchment area, leading to greater distances between students and their families compared to those in Frankfurt.

4.2 Students' self-perception as temporary residents

In the quantitative survey, we asked students, “Would you describe yourself as a person who only resides in this place for a certain period of time”? This unique approach relies on students' own perceptions of their living arrangements as temporary rather than predefined categories. The survey revealed that 65 % (n=433) of students who relocated to the university cities perceived themselves as temporary residents, with no significant difference observed between the two cities. In contrast, only 33 % of students who had already lived in the city prior to their studies identified as temporary residents. This finding suggests that moving to the university city for the purposes of higher education is associated with a greater sense of temporality than is experienced by those who have resided there for a longer period.

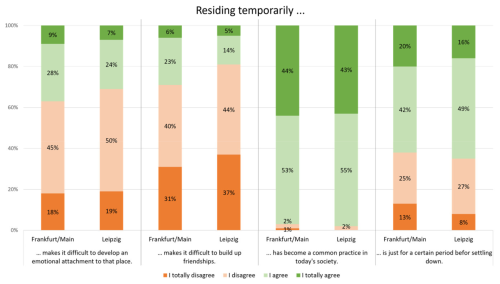

To further explore students' perceptions of this sense of impermanence, we asked those who relocated to the university city and consider themselves as temporary residents to indicate their level of agreement or disagreement with four statements (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2Evaluation of statements to assess the impact of temporary living arrangements (participants who moved to the university city and identify as temporary residents; ).

The figure illustrates that students in both Frankfurt and Leipzig share largely similar perceptions of temporary residence. A substantial majority of students in both cities indicated that the temporary nature of their living arrangements does not hinder their ability to form emotional attachments to their place of residence (Frankfurt: 63 %; Leipzig: 69 %). Furthermore, a significant portion of these students believe that temporary living does not hinder the development of friendships, as indicated by 71 % in Frankfurt and 81 % in Leipzig. This finding suggests that students can establish social networks even when they perceive their stay as temporary. The slightly higher agreement among students in Leipzig may reflect the city's appealing “vibe” and student-oriented environment, which fosters connections among young individuals at similar life stages. Nearly all students in both cities recognise temporary living as a prevalent practice in contemporary society, highlighting its significance within the student demographic. Nevertheless, over 60 % of students in both cities express a desire to settle down in the future. Additionally, a majority (67 %) report a positive assessment of their temporary living arrangements. Importantly, no significant differences were observed across specific sociodemographic variables, such as gender or age. This lack of variation is likely attributable to the relative homogeneity of the student sample, which predominantly comprises individuals at similar life stages.

Future residential preferences also influence how students perceive their current living arrangements as temporary. Among those who relocated to the university cities, 27 % expressed a desire to continue residing in their current residence as they transition to the next stage of their lives. Interestingly, this preference is slightly more pronounced in Frankfurt (32 %) compared to Leipzig (23 %). Conversely, 32 % of students expressed a preference to live elsewhere, with this sentiment being fairly consistent across both cities (Frankfurt: 34 %; Leipzig: 30 %). However, a noteworthy distinction arises in the level of uncertainty regarding future living arrangements: 41 % of students reported being unsure about where they would like to live in the future, with a lower percentage of uncertainty in Frankfurt (34 %) compared to Leipzig (47 %). These findings suggest that students in Frankfurt are more inclined to remain in their current residence, while those in Leipzig exhibit greater uncertainty about their future places of residence.

During the qualitative interviews, we asked students whether they considered their living situation in the university city as temporary or permanent. Definitions of “temporary” and “permanent” varied widely among respondents; for some, “permanent” meant “forever” or, as one student put it, “until I die” (L12). However, most students associated “permanent” with a timeframe of “for a while” or “for an indefinite period”. Generally, “temporary” was understood as “for a certain time”, with the specifics shaped by various aspects. Ultimately, students' self-perceptions of their situations as temporary were influenced by temporal boundaries, aspirations for the future and emotional attachments to their current places of residence.

Interestingly, while the distinction between “temporary” and “permanent” is fundamentally temporal, the duration of residence is frequently considered less significant in the individual definitions. Many interviewees associated their timeframes with the duration of their studies, typically corresponding to specific academic programmes – such as 3 years for a Bachelor's degree or 6 years for both Bachelor's and Master's. However, one interviewee, despite being on a similar timeline, perceived themselves as a permanent resident: “As I have already lived here for 6 years and will probably be here for at least another 2 or 3 years, I feel I have arrived here and actually live here permanently” (L5).

The students' aspirations for the future revealed a diverse range of perspectives: approximately one-third expressed a desire to leave the city for the next stage of their lives, another third wished to remain, and the final third was uncertain about their plans. For some, the intention to leave is a key factor in their identification as temporary residents, as one student noted: “Afterwards, I would like to move”. (L9). Many students view their time at university as a distinct phase that will eventually conclude, as illustrated by the following quote: “Well, it's temporary. I don't think I want to spend the rest of my life here; it's a stage, but it's a stage of my life that is of equal value to the others” (L14). The limited employment opportunities in their fields further contributed to some students' perceptions of themselves as temporary residents, as they anticipated needing to relocate for employment. Conversely, some students identified as permanent residents due to the lack of clarity regarding their future plans: “I think that as long as there is no specific alternative plan, I would say that I live here permanently” (L2). For many, the transition to a more permanent living situation is associated with significant life milestones, such as starting a family or securing full-time employment.

Another foundation for students' perceptions of temporality is their sense of emotional attachment to their place of residence. As illustrated by the statement “I have arrived here” (L5), this emotional “arrival” appears to be the decisive factor for many considering themselves as permanent residents, even within a limited timeframe. For some interviewees, the sense of being established in the university city signifies a permanent residence that transcends temporal boundaries. The process of building a social network and familiarising oneself with the city also plays a role in this context. One student expressed that they “already feel like a local” (F5), while another student noted feeling “comfortable with the fact that Leipzig is now my new home. I can definitely imagine staying here for quite a while” (L16). These feelings of place attachment will be discussed further in the next section.

4.3 Perceptions of place attachment, belonging and home among university students

This section focuses on students' emotional spatial attachment to their university cities. Through qualitative interviews with students who relocated to a university city, we explored their attachments, identification and feelings of home within the city. Most students expressed attachment to the city (place attachment), attributing this sentiment to various factors. The most frequently cited reason for this attachment was the social environment. As one student explained, “Because I have built up my whole social environment here. … All my friends and girlfriend and, of course, my flat share., … I would say that makes me feel attached to Leipzig” (L3). The presence of friends and peers appeared to play a decisive role in shaping students' attachments to the city. Additional factors contributing to their sense of attachment included the city's amenities, such as recreational areas, cultural offerings and specific locations like a favourite pub. A sense of belonging as a student in a vibrant academic community enhances this attachment, with particular places – such as the campus – serving as key triggers for feelings of belonging.

Students who relocated to the university city often identify with the community, attributing this to various cultural aspects. In Frankfurt, for instance, local customs, humour, and traditional dishes – such as the iconic “green sauce” and apple wine – play a significant role in this identification, along with support for the local soccer club. For some students, embracing these elements signifies their integration into the urban community. Furthermore, students resonate with characteristics commonly associated with the city, such as its internationality, multiculturalism and vibrant “young student population” (L24). In the case of Leipzig, students also identify with the political environment as “a left-wing stronghold” (L24) and its alternative cultural scene. This sense of belonging can be so profound that some students describe themselves as “Frankfurters” or “Leipzigers”. As one student noted, “After 5 years, I would definitely describe myself as a Leipziger, as a Leipzig resident. I definitely feel very comfortable here” (L21).

When exploring the concept of home, a differentiated perspective emerges among students. Many described their university cities as home, viewing them as the centre of their daily lives, which includes their physical residences. Students' definitions of “home” were often quite pragmatic, describing it as “where you always go and go to sleep” (F20), “where my cell phone automatically logs into the Wi-Fi” (F21) and “where you come back at night drunk and still know where you are” (L27). However, the notion of home is also influenced by the social environment. As one student noted, “Home is often also the people and not necessarily the city” (L25). Generally, home was associated with “feeling good”, “feeling safe” and “feeling accepted”. In some instances, students mentioned multiple “homes”, with their family residence typically serving as a second home. The term Heimat (home, place of origin) was often used to describe their “roots” (F15, L9, L19). For international students, Heimat typically refers to their country of origin, often linked to where parents and family reside. This connection is imbued with memories and experiences, resulting in strong emotional and physical ties to these places. Overall, the term Heimat appears to convey a stronger sense of connection than the term Zuhause, suggesting that Heimat is associated with a feeling of being “truly settled” (L1).

Many interviewees expressed that their feelings of attachment and sense of home have developed over time. A home can evolve into a Heimat through the development of strong emotional connections and the establishment of social networks. For some participants, their university cities have become a Heimat, with one student describing it as a “chosen home” (L1). In certain cases, feelings of home are accompanied by a distancing from their parental homes, particularly when the connection to that place is weak or diminished.

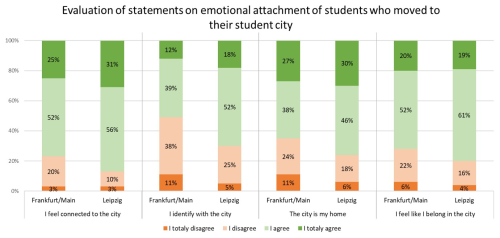

In the quantitative survey, four statements were employed to assess students' sense of place attachment, reflecting four dimensions of this concept as outlined by Raymond et al. (2010): attachment to the university city, identification with the university city, perception of the city as home and feelings of belonging to the university city. Figure 3 compares students' emotional attachments to their university cities in Frankfurt and Leipzig. Overall, the response patterns are quite similar across both cities, with only minor variations in the levels of agreement. The findings indicate that students who relocated to the university city in recent years predominantly expressed agreement with the statement regarding their connection to the city (Frankfurt: 77 %; Leipzig: 87 %) and their feelings of belonging (Frankfurt: 72 %; Leipzig: 80 %). Notably, students in Leipzig were more inclined to perceive the city as their home (76 %) compared to those in Frankfurt (65 %). Across all four statements pertaining to emotional attachment, students in Leipzig reported slightly higher levels of agreement than their counterparts in Frankfurt. The most significant disparity is observed in the statement, “I identify with the city”, where 70 % of students expressed agreement compared to 51 % in Frankfurt. This observation aligns with the earlier finding that many students choose Leipzig because of the city's overall “vibe”. It is suggested that Leipzig's vibrant, student-oriented atmosphere, coupled with its diverse cultural and social offerings, cultivates an environment that fosters a strong sense of identification with the city among students despite being temporary residents.

Figure 3Student's emotional attachment to the university city (only those who moved to the university city; n=671).

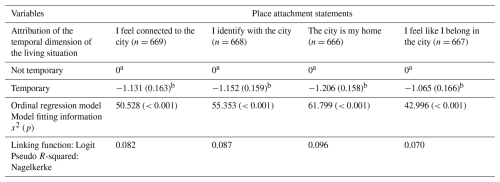

To investigate the impact of temporality on students' emotional attachment, the following ordinal regression analysis (Table 2) compares students who perceive themselves as temporary residents with those who do not share this perception. Consistent with the qualitative data, it is evident that students identifying as temporary residents report a statistically lower level of agreement with all four statements. This finding suggests that they generally experience a weaker emotional attachment to their current city compared to those who do not consider themselves temporary residents.

An analysis of the differences between the statements reveals that students identifying as temporary residents are most likely to agree with the statement regarding their sense of belonging in the city (−1.065) and their feelings of connection to it (−1.131). However, they are less likely to identify with the city (−1.152) or to perceive it as home (−1.206). These findings highlight the crucial role of temporary living arrangements in shaping students' connection and sense of belonging to their city.

Table 1Results of the ordinal regression model (only those who moved to the university city).

a Parameter is set to zero because it is the reference category. Standard errors in parentheses. b Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level. Place attachment items were measured on a scale ranging from 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Agree, 4 = Strongly Agree.

Both the quantitative and qualitative results indicate interactions between self-perceptions as either temporary or permanent residents and the feeling of being at home. A strong emotional attachment strengthens the perception of permanence and fosters an intention to remain in the city. Conversely, viewing oneself as a permanent resident can also reinforce feelings of attachment to the city.

In the following section, we will analyse the results to address our research questions. The first two questions explore students' reasons for relocating to the university cities and their self-perception as temporary residents. These insights provide context for the third question, which examines how these factors influence their emotional attachment to the university city.

Our findings indicate that the reasons for relocating to Frankfurt are primarily study-related, while city-related factors play a more significant role in students' decision to relocate to Leipzig. In Frankfurt, in particular, familial proximity emerges as a key factor influencing students' choice of university city, a trend also observed by Hardouin and Moro (2014) in France. Additionally, the broader social and economic contexts of the two cities contribute to these differences. In Leipzig, affordable rents and a generally lower cost of living are decisive factors for many students, whereas higher rental costs in Frankfurt were frequently cited as a drawback. Furthermore, many students are drawn to Leipzig due to the city's “vibe”, which is closely linked to their sense of place attachment. Overall, the influx of students is closely linked to the reputation of the university and the image of the city. It can be assumed, that the reasons for relocation influence the extent to which students perceive their living arrangements as temporary.

Regarding students' self-identification as temporary residents, it is noteworthy that the majority of those who relocate to the university cities view themselves as such. Interestingly, students in temporary living arrangements do not perceive these circumstances as negatively impacting their emotional attachment to their place of residence or their ability to form friendships. However, qualitative interviews reveal that the perceptions of what constitutes “temporary” or “permanent” vary among individuals. Some students identify as permanent residents despite being aware that their time in the city is limited, as they experience a strong sense of belonging. This finding contrasts with the results of a study by Balloo et al. (2021) in the UK, which revealed that students are aware of their temporary status in the university city and, as a result, tend to avoid forming deep attachments. This difference may be due to structural variations in the housing markets or expectations around student life and transitions to adulthood between Germany and the UK. Another reason for these differences in the emotional attachment of students in the UK and Germany is probably that German students are much more likely than UK students to stay at their university residence during the lecture-free period (Kramer, 2019; Smith, 2005). Nevertheless, many students associate milestones such as starting their own family or securing permanent employment with the transition to a more permanent living arrangement.

To examine the perception of temporary living arrangements, we analysed various dimensions of emotional spatial attachment to the university cities. The results clearly demonstrate that students in temporary living arrangements exhibit lower levels of place attachment and identification with the city, a weaker perception of the city as their home and a diminished sense of belonging compared to non-temporary students. These findings align with previous studies in the UK that differentiate between local and non-local students (Pokorny et al., 2017; Holton and Finn, 2020). Importantly, a strong emotional spatial attachment appears crucial for students, as it is associated with increased subjective well-being (Lee et al., 2015) and a reduction in homesickness (Scopelliti and Tiberio, 2010).

The qualitative interviews further revealed that the concept of home can encompass multiple locations rather than being confined to a single place (Boccagni and Kusenbach, 2020). Students with multiple residences often report feeling at home in the university city, aligning with the notion of “polytopicity” proposed by Stock (2024). However, their emotional attachment to their family's place of residence tends to be stronger, corroborating the findings of a quantitative study by Cicognani et al. (2011) in Portugal, which investigated place identity and sense of community among university students who had relocated for academic reasons.

Insights into the extent to which structural factors influence students' future plans can be derived from individual statements made in the qualitative interviews. These statements revealed that employment opportunities significantly shape students' intentions to either remain in or leave the city, as well as their perceptions of temporariness. Additionally, the housing market, which students perceive as significantly tighter in Frankfurt, was frequently cited as a reason for potentially leaving the university city after completing their studies. The influence of citizenship status on these decisions could not be examined, as international students were underrepresented in our study. Additionally, the qualitative interviews indicated that new communication technologies may influence students' attachments to their living environments, an aspect that warrants exploration in future research. Integrating these dimensions into subsequent studies could provide a more nuanced understanding of how various factors contribute to the development of place attachment among students.

In this study, we employed a mixed-method approach to explore how students who relocate to one of two university cities perceive themselves as temporary residents and the impact of this perception on their emotional spatial attachments. Our research is grounded in a standardised survey, and qualitative interviews conducted in the German university cities of Frankfurt am Main and Leipzig. The move to a university city marks the beginning of a distinct living arrangement, making the reasons for relocation significant. Our findings indicate that the students' decisions to move are shaped not only by individual motivations but also by the urban structure and image of the university city, revealing notable differences between Frankfurt and Leipzig. A key analytical contribution of this study is how students themselves classify their living arrangements as “temporary”, rather than having this classification imposed externally. This self-identification reflects individual negotiations of place attachment, future planning and the meaning of residence. A substantial proportion of respondents describe themselves as temporary residents and view their living arrangements positively. Nevertheless, these students also express a desire to settle down in the future. Additionally, we analysed various dimensions of emotional attachment and found that students in temporary living arrangements exhibit significant differences in their emotional spatial attachment to their university city compared to non-temporary students. Overall, our results suggest that perceptions of temporary and permanent living arrangements are highly subjective but are simultaneously influenced by the structure of the cities where students live. For example, students in Frankfurt have developed somewhat less strong ties to the city, which may indicate that they are worried about being able to afford the city in the long term in view of the tight housing market. These complex findings highlight the necessity for a nuanced understanding of temporary living arrangements and their effects on students' lives. Such an understanding is essential for grasping the specific aspirations of this demographic, which not only constitutes a significant proportion of the population as a “standing wave” but also includes many individuals who could potentially transition into permanent residents in the future.

The findings of this study offer valuable insights for various stakeholders, enhancing our understanding of how students adapt to their university cities, establish a sense of home and navigate specific living situations. For researchers, our results provide a foundation for further investigation into the dynamics of students' living arrangements and their implications for social cohesion and urban development.

For reasons of anonymity, the qualitative interview data cannot be made publicly accessible, as fully anonymizing the transcripts would require considerable additional effort. The quantitative data can be made available upon request once ongoing projects are completed.

All authors contributed equally to conceptualization, analysis, visualization, and writing of the manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

We thank the students who participated in our seminars and supported data collection for this study through their engagement and contributions.

This paper was edited by Hanna Hilbrandt and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Altman, I. and Low, S. M. (Eds.): Place Attachment: Human Behavior and Environment (Advances in Theory and Research), 12th edn., Springer, Boston, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-8753-4, 1992.

Bailey, E., Devine-Wright, P., and Batel, S.: Emplacing linked lives: A qualitative approach to understanding the co-evolution of residential mobility and place attachment formation over time, Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 31, 515–529, https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2533, 2021.

Balloo, K., Gravett, K., and Erskine, G.: “I'm not sure where home is”: narratives of student mobilities into and through higher education, Brit. J. Sociol. Educ., 42, 1022–1036, https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2021.1959298, 2021.

Belina, B. and Miggelbrink, J.: Hier so, dort anders. Zum Vergleich von Raumeinheiten in der Wissenschaft und anderswo Einleitung zum Sammelband, in: Hier so, dort anders: Raumbezogene Vergleiche in der Wissenschaft und anderswo, edited by: Belina, B. and Miggelbrink, J., Westfälisches Dampfboot, Münster, 7–39, ISBN 9783896917690, 2010.

Bettencourt, G. M.: “I belong because It wasn't made for me”: Understanding working-class students' sense of belonging on campus, J. High. Educ., 92, 760–783, https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2021.1872288, 2021.

Blunt, A. and Dowling, R.: Home, Routledge, London, 347 pp., https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429327360, 2022.

Boccagni, P. and Kusenbach, M.: For a comparative sociology of home: Relationships, cultures, structures, Curr. Sociol., 68, 595–606, https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392120927776, 2020.

Carifio, J. and Perla, R.: Ten common misunderstandings, misconceptions, persistent myths and urban legends about likert scales and likert response formats and their antidotes, Journal of Social Sciences, 3, 106–116, 2007.

Cicognani, E., Menezes, I., and Nata, G.: University students' sense of belonging to the home town: The role of residential mobility, Soc. Indic. Res., 104, 33–45, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9716-2, 2011.

Cieraad, I.: Homes from home: Memories and projections, Home Cult., 7, 85–102, https://doi.org/10.2752/175174210X12591523182788, 2010.

Destatis – Statistisches Bundesamt: Schnellmeldungsergebnisse der Hochschulstatistik zu Studierenden und Studienanfänger/-innen, https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bildung-Forschung-Kultur/Hochschulen/Publikationen/Downloads-Hochschulen/schnellmeldung-ws-vorl-5213103238004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (last access: 16 June 2025), 2022.

Di Masso, Andrés, Williams, Daniel R., Raymond, Christopher M., Buchecker, Matthias, Degenhardt, Barbara, Devine-Wright, Patrick, Hertzog, Alice, Lewicka, Maria, Manzo, Lynne, Shahrad, Azadeh, Stedman, Richard, Verbrugge, Laura, and von Wirth, Timo: Between fixities and flows: Navigating place attachments in an increasingly mobile world, J. Environ. Psychol., 61, 125–133, 2019.

Dost, G. and Mazzoli Smith, L.: Understanding higher education students' sense of belonging: a qualitative meta-ethnographic analysis, Journal of Further and Higher Education, 47, 822–849, https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2023.2191176, 2023.

Dowling, R. and Mee, K.: Home and homemaking in contemporary Australia, Hous. Theory Soc., 24, 161–165, https://doi.org/10.1080/14036090701434276, 2007.

Easthope, H.: A Place Called Home, Hous. Theory Soc., 21, 128–138, 2004.

Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF): Federal Training Assistance Act (BAföG), https://www.bmbf.de/EN/Education/HigherEducation/Funding/Bafoeg/bafoeg.html (last access: 16 June 2025), 2024.

Flick, U.: Qualitative Sozialforschung: Eine Einführung, 10. Auflage, Rororo Rowohlts Enzyklopädie, rowohlts enzyklopädie im Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg, 623 pp., ISBN 978-3-499-55694-4, 2007.

Glatter, J., Hackenberg, K., and Wolff, M.: Zimmer frei? Die Wiederentdeckung der Relevanz des studentischen Wohnens für lokale Wohnungsmärkte, RuR, 72, 385–399, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13147-014-0303-x, 2014.

Greinke, L.: The multi-locality of students during COVID-19 and its effects on spatial development: A quantitative case study of Leibniz University Hanover, Traditiones, 52, 71–97, 2023.

Gustafson, P.: Roots and Routes, Environ. Behav., 33, 667–686, https://doi.org/10.1177/00139160121973188, 2001.

Hardouin, M. and Moro, B.: Étudiants en ville, étudiants entre les villes. Analyse des mobilités de formation des étudiants et de leurs pratiques spatiales dans la cité, norois, 230, 73–88, https://doi.org/10.4000/norois.5032, 2014.

Hägerstrand, T.: Time-geography: focus on the corporeality of man, society and environment, in: The Science and Praxis of Complexity, edited by: Aida, S., United Nations University Press, Tokyo, 193–216, 1985.

Hilti, N.: Lebenswelten multilokal Wohnender: Eine Betrachtung des Spannungsfeldes von Bewegung und Verankerung, Stadt, Raum und Gesellschaft, 25, Springer VS, Wiesbaden, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-01046-1, 2013.

Holton, M.: “I already know the city, I don't have to explore it”: Adjustments to `sense of place' for `local' UK University Students, Popul. Space Place, 21, 820–831, https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1866, 2015.

Holton, M. and Finn, K.: Belonging, pausing, feeling: a framework of “mobile dwelling” for U.K. university students that live at home, Applied Mobilities, 5, 6–20, https://doi.org/10.1080/23800127.2018.1477003, 2020.

Infas – Institut für angewandte Sozialwissenschaft GmbH: Fürs Studium in die große weite Welt? Nicht unbedingt, https://www.infas.de/fuers-studium-in-die-grosse-weite-welt-nicht-unbedingt/ (last access: 16 June 2025), 2015.

Kramer, C.: Studierende im städtischen Quartier – zeit-räumliche Wirkungen von temporären Bewohnern und Bewohnerinnen, in: Zeitgerechte Stadt: Konzepte und Perspektiven für die Planungspraxis = Temporal justice in the city concepts and perspectives for planning practise, edited by: Henckel, D. and Kramer, C., Akademie für Raumforschung und Landesplanung Leibniz-Forum für Raumwissenschaften, Hannover, 281–310, https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-64659-8 (last access: 25 August 2025), 2019.

Kroher, M., Beuße, M., Isleib, S., Becker, K., Ehrhardt, M.-C., Gerdes, F., Koopmann, J., Schommer, T., Schwabe, U., Steinkühler, J., Völk, D., Peter, F., and Buchholz, S.: Die Studierendenbefragung in Deutschland: 22. Sozialerhebung: Die wirtschaftliche und soziale Lage der Studierenden in Deutschland 2021, Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, https://www.dzhw.eu/pdf/ab_20/Soz22_Hauptbericht.pdf (last access: 25 August 2025), 2023.

Landolt, S. and Frey, H.: Das “Zuhause”: Wie Studierende im Lockdown diesen Raum neu aushandeln, ZORA (Zurich Open Repository and Archive), GeoAgenda, 4, 14–17, https://doi.org/10.5167/UZH-193061, 2020.

Lee, J. H., Davis, A. W., and Goulias, K. G.: Exploratory analysis of the relationships among long distance travel, Sense of place, and subjective well-being of college students, 94th Annual Transportation Research Board Meeting, Washington, D.C., 11–15 January 2015, Geotrans Report – 2014-8-01, Santa Barbara, CA, 2015.

Lewicka, M.: What makes neighborhood different from home and city? Effects of place scale on place attachment, J. Environ. Psychol., 30, 35–51, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JENVP.2009.05.004, 2010.

Massey, D.: For space, London, UK: Sage Publications, ISBN 1-4129-0362-9, 2005.

McCullagh, P.: Regression models for ordinal data, J. Roy. Stat. Soc. B Met., 42, 109–127, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1980.tb01109.x, 1980.

Moghisi, R., Mokhtari, S., and Heidari, A. A.: Place attachment in university students. Case study: Shiraz University, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 170, 187–196, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.028, 2015.

Nadler, R.: Von der präsenten Heimat zum appräsenten Zuhause? Multilokalität und kreative Wissensarbeiter/innen, in: Hier und dort: Ressourcen und Verwundbarkeiten in multilokalen Lebenswelten, edited by: Duchêne-Lacroix, C. and Maeder, P., Schwabe Verlag, Basel, 55–69, 2013.

Nadler, R.: Plug&Play Places: Lifeworlds of Multilocal Creative Knowledge Workers, De Gruyter Open, Warschau/Berlin, 424 pp., https://doi.org/10.2478/9783110401745.fm, 2014.

Plano Clark, V. L., Huddleston-Casas, C. A., Churchill, S. L., O'Neil Green, D., and Garrett, A. L.: Mixed Methods Approaches in Family Science Research, J. Fam. Issues, 29, 1543–1566, https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X08318251, 2008.

Pokorny, H., Holley, D., and Kane, S.: Commuting, transitions and belonging: the experiences of students living at home in their first year at university, High Educ., 74, 543–558, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0063-3, 2017.

Qingjiu, S. and Maliki, N. Z.: Place attachment and place identity: Undergraduate students' place bonding on campus, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 91, 632–639, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.463, 2013.

Raymond, C. M., Brown, G., and Weber, D.: The measurement of place attachment: Personal, community, and environmental connections, J. Environ. Psychol., 30, 422–434, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.08.002, 2010.

Region Frankfurt: Auf den Punkt gebracht: Die Metropolregion FrankfurtRheinMain. Regionales Monitoring 2022, https://www.region-frankfurt.de/Services/Veröffentlichungen/ (last access: 16 June 2025), 2024.

Rioux, L., Scrima, F., and Werner, C. M.: Space appropriation and place attachment: University students create places, J. Environ. Psychol., 50, 60–68, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.02.003, 2017.

Scopelliti, M. and Tiberio, L.: Homesickness in University Students: The Role of Multiple Place Attachment, Environ. Behav., 42, 335–350, https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916510361872, 2010.

Smith, D. P.: “Studentification”: The gentrification factory?, in: Gentrification in a global context: The new urban colonialism, transferred to digital print, edited by: Atkinson, R., Routledge, London, New York, 72–89, 2005.

Schipper, S.: Kommunale Bürgerbegehren und die Wohnungsfrage. Der “Mietentscheid” in Frankfurt und sein schwieriges Verhältnis zur institutionellen Politik, Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen, 36, 63–78, https://doi.org/10.1515/fjsb-2023-0006, 2023.

Stadt Frankfurt am Main: Wirtschaft in Frankfurt, https://frankfurt.de/themen/wirtschaft (last access: 16 June 2025), 2024.

Stadt Leipzig: Wirtschaftsbericht 2023 – Starkes Wachstum, https://www.leipzig.de/wirtschaft-und-wissenschaft/wirtschaftsbericht (last access: 16 June 2025), 2025a.

Stadt Leipzig: Bautätigkeit und Wohnen, Wohnungsmieten: Grundmiete, https://statistik.leipzig.de/statdist/table.aspx?cat=6&rub=6 (last access: 16 June 2025), 2025b.

Statista GmbH: Würden Sie für Ihren Arbeitsplatz gegebenenfalls in eine andere Region Deutschlands umziehen?, https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/13420/umfrage/einstellung-von-studenten-zur-beruflichen-umzugsbereitschaft-innerhalb-von-deutschland (last access: 16 June 2025), 2022.

Stedman, R. C.: Understanding Place Attachment Among Second Home Owners, Am. Behav. Sci., 50, 187–205, https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764206290633, 2006.

Stock, M.: “Touristisch wohnet der Mensch”: Zu einer kulturwissenschaftlichen Theorie der mobilen Lebensweisen, Voyage: Jahrbuch für Reise- & Tourismusforschung, 10 pp., 186–201, 2014.

Stock, M.: Eine theoretische Geographie der Räumlichkeit? Überlegungen anhand des Begriffs “Wohnen”, Geogr. Z., 112, 237–256, 2024.

Tuan, Y.-F.: Rootedness versus sense of place, Landscape, 24, 3–8, 1980.

Universität Frankfurt: Jahrbuch 2023, https://aktuelles.uni-frankfurt.de/jahrbuch-2023-daten-fakten (last access: 16 June 2025), 2024.

Universität Leipzig: Porträt der Universität Leipzig, https://www.uni-leipzig.de/universitaet/profil/portraet (last access: 16 June 2025), 2024.

Urry, J.: Sociology Beyond Societies: Mobility for the Twenty-First Century, London, Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203021613, 1999.

Vogelpohl, A.: Qualitativ vergleichen – Zur komparativen Methodologie in Bezug auf räumliche Prozesse, in: Raumbezogene qualitative Sozialforschung, edited by: Rothfuß, E. and Dörfler, T., Springer VS, Wiesbaden, 61–82, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-93240-8_3, 2013.

Weichhart, P.: Heimat, raumbezogene Identität und Descartes' Irrtum, in: Heimat: Ein vielfältiges Konstrukt, edited by: Hülz, M., Kühne, O., and Weber, F., Springer VS, Wiesbaden, 53–66, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-24161-2_3, 2019.

Williams, D. R. and Patten, S. R.: Home and away?: Creating identities and sustaining places in a multi-centered world, in: Multiple Dwelling and Tourism: Negotiating Place, Home, and Identity, edited by: McIntyre, N., Williams, D., and McHugh, K., CABI Publishing, Cambridge, 32–50, 2006.

Winther, I. W.: “Homing oneself”: Home as a practice, Haecceity Papers, 4, 49–83, 2009.

BAföG” (Bundesausbildungsförderungsgesetz) is a German federal student financial aid programme that provides grants and interest-free loans to support students during their studies (Federal Ministry of Education and Research, 2024).