the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Death marks in the city – contesting the signature of gendered necropolitics in Vitória, Brazil

Igor Martins Medeiros Robaina

Paloma Barcelos Teixeira

Jan Simon Hutta

Focusing on the aftermath of the abduction, rape and killing of an 8-year-old girl in Vitória, the paper argues that the violent event has left various traces that index a necropolitical power formation oriented towards hegemonic political and economic actors. The traces range from physical marks of violence to indications of obfuscation and manifestations of support for the aggressors. Such support was expressed, for example, by the city council's vote to retain a street name that honours the family of one of the alleged perpetrators. To analyse necropolitics through such traces, we draw on Mitchell Dean's discussion of the “signature of power” alongside works on feminicide, counter-forensics and contested toponymy. Thus reading necropolitics through its signature, we argue, sheds light on its specific context of formation and allows for scrutinizing the specific strategies and material elements through which necropolitics unfolds its deadly effects.

- Article

(5715 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

The city waits and aches. The little grasses

Crack through stone, and they are green with life.

(Sylvia Plath, Three Women. A Poem for Three Voices; Plath, 1968)

A vibrant mural adorns the Araceli Cabrera Crespo viaduct in the Brazilian city of Vitória (Fig. 1). A ribbon beneath the eponym's face reads “18 de maio”, referring to a girl's death on 18 May 1973. Despite being located at the margins of the city, with its 1400 m2, the mural has a notable presence in the state of Espirito Santo's capital. And yet, the colourful artwork hides more than it reveals. An abundance of flowers, smiling faces, angel wings, teddies and children's toys gloss over the brutality of an event that involved the abduction, rape, imprisonment, murder and subsequent attempted dissolution in acid of 8-year-old Araceli Cabrera Sánchez Crespo, commonly referred to as Araceli. Nothing in the mural speaks of this violence or the state's failure to dispense justice in its wake. Araceli's alleged perpetrators, from families of the regional political and economic elite, have never been convicted. More than 50 years after the violent event, the wound it has inflicted on the city and on Brazil as a whole is still open, stitched up bunglingly with representational gestures.

Importantly, the atrocious event is not an isolated occurrence so much as the expression of conditions of violence pervasive in Brazilian society. On the mural, next to Araceli, we see an image of Fabiane Isadora, a 2-year-old girl who was beaten, raped and murdered in 2017 by her stepfather in revenge against the girl's mother. Both cases are at the intersection of various forms of violence that are recursively committed, mostly by men, against children, girls and women, including trans women (see Campos, 2015). Drawing on earlier works on femicide, Mexican anthropologist and activist Marcela Lagarde (1997, 2006) has coined the term “feminicide” (feminicidio) to denounce the wilful elimination of women that is supported by social processes of gendered oppression (cf. Frías, 2023; Olamendi, 2016).1 Specifically, the notion of feminicide draws attention to discourses and structures that lead to the blaming of victims, the exculpation and invisibilization of perpetrators, and the state's failure to dispense justice. Further, the intersectional character of these events is exemplified by the fact that Araceli Cabrera Crespo, the daughter of immigrants, lived in the peripheral neighbourhood of Fátima outside Vitória in the municipality of Serra. Those affected by feminicide and further forms of violence in Brazil are disproportionately poor, of colour and from peripheralized spaces.

The debate on necropolitics in political geography and anthropology in the wake of Achille Mbembe's (2003) influential essay of the same name opens up productive pathways for interrogating the power techniques and spatial dynamics at work in such gendered patterns of killings with impunity. Connecting to works on colonialism and racial capitalism, writings on necropolitics highlight how power is established through systematically exposing subaltern populations to death (for a comprehensive overview, see Hutta, 2025). In relation to Abya Yala/Latin America, scholars have emphasized how necropolitics is shaped by the entangled histories of extractive accumulation and plantation slavery: how the structurally white elites have long used torture and lethal violence against racialized populations to appropriate land, generate wealth and assert political hegemony, all the while ensuring their own impunity (e.g. Alves, 2018; Eichen, 2020; Mendiola and Vasco, 2017; Ruette-Orihuela et al., 2023; Smith, 2013). In the context of Vitória, the very name of the city (“victory”) bespeaks the colonizers' establishing of hegemony via the elimination of indigenous populations. Particularly relevant to our present analysis, several works have fleshed out gendered dynamics of necropolitics that target women's and trans people's personal and social existences, including through stigmatization, rape and killings – often linked to forms of exploitation, displacement and dispossession (Hutta, 2022; Lopes et al., 2024; Sahraoui, 2024; Smith, 2016a; Wright, 2011; see also Hartman, 1997; Davis, 1981; Segato, 2016; Zaragocin, 2019).

But more specifically, the case of Araceli also speaks to the widespread use of forced disappearance and techniques of obfuscation that enable perpetrators' impunity (Araújo, 2016; Hutta, 2025; see also Wright, 2017). The very intelligibility of this case is conditioned by a long series of obfuscations that began five decades ago with the girl's forced disappearance, continued with the investigations, and had not finished with the commissioning of the mural in 2017. This, therefore, is more than a textbook case of necropolitics, as it eludes approaches not only to necropolitics focused on spectacular uses of exceptional violence (e.g. Alves, 2014; Smith, 2016b), but also to those centring the “slow violence” of environmental degradation (e.g. Souza, 2021; Tornel, 2024). At a methodological level, it calls for moving beyond a focus on explicit discourse, an analytic bedrock of much Foucault-inspired work on power, towards the traces, marks and scars these events have left in and on urban space in the context of reiterative contestations (see also Navaro, 2020).

To develop a methodological approach to analysing necropolitics through its marks and traces, we draw on the discussion on “counter-forensics” in political anthropology and geography (e.g. Abbott and Lally, 2025; Ferrándiz and Robben, 2015; Hagerty, 2023; Huffschmid, 2015) alongside engagements with urban toponymy (e.g. Alderman and Inwood, 2013; Rose-Redwood et al., 2010; Wideman and Masuda, 2018). While counter-forensics aims at reconstructing and memorializing violent events through hidden traces, engagements with toponymy connect street and place names to their conditions of emergence, preservation and contestation – an issue of great relevance to the viaduct that bears the mural of Araceli Cabrera Crespo and Fabiane Isadora. Further, to move towards an expanded analysis of necropolitics, we draw on Giorgio Agamben's (2009) discussion of the signature as a meta-inscription that enables the signs within a semiotic field to be read in particular ways. Reading the signature of necropolitics through traces of both violence and obfuscation, we argue, opens new pathways to scrutinizing how seemingly disparate practices, matters and discourses coalesce around powerful hegemonies and strategies of power.

In what follows, we will first summarize the main course of the violent event and the subsequent investigation. We will then spotlight some of the traces that emerged in this context in order to read them through their necropolitical signature. Specifically, we will interrogate a series of contestations around urban toponyms that preceded the inauguration of the Araceli Cabrera Crespo viaduct and that point to ongoing struggles around naturalizing or dismounting necropolitical signatures in public space. We will anchor this discussion in an account of Vitória's transformation in the mid-20th century from a regional trade hub into an internationally connected industrial centre, so as to flesh out the spatial underpinnings of this more-than-exceptional necropolitics.

On 18 May 1973, 8-year-old Araceli Cabrera Crespo left her home in the Fátima neighbourhood, in the municipality of Serra, bound for Colégio São Pedro, located in the Praia do Suá neighbourhood, in the municipality of Vitória, and never returned.2 As her parents later stated, Araceli travelled the same route by bus every day (Quintino and Chagas, 2023). The bus stop was 400 m from the school, on a busy avenue, next to a bar. On that day Araceli was distracted by a cat and ended up missing her bus home, at least according to police reports. As she did not return, her parents went looking for her at the school and subsequently informed the authorities, who confirmed the girl's disappearance (Louzeiro, 1976).

Unlike in innumerable other cases of forced disappearance in Brazil, in this case, Araceli's body reappeared 6 d later, on 24 May. A 15-year-old teenager who was catching birds in a vacant lot spotted numerous vultures and, on approaching, saw a human body lying in a ditch. The body was that of a naked, mutilated, burnt child with numerous bite marks all over, as well as signs of sexual abuse. The face was practically unrecognizable due to the effects of corrosive acids, which looked like intentional efforts had been made to hinder identification of the corpse.

What thus appeared along with the girl's body were incisive traces of brutal violence, as well as of attempts to obfuscate it. In the ensuing investigations, further indications of attempted obfuscation surfaced in a series of mismatches, contradictions and further acts of violence. According to a report in the newspaper A Gazeta from 25 May 1973, once the police had summoned the parents to identify the body at Vitória's department of forensic medicine, the mother, in a state of shock, stated that it was not her daughter, while the father, by contrast, claimed to recognize the body by older scar marks. More gravely, the police commissioner in charge of the case claimed that Araceli was still alive and that this was someone else's body that “must have been picked up in a cemetery or some other place and dumped there to confuse the police” (A Gazeta, 1973a:14).3 More than 2 months later, the results of a forensic examination comparing the body's hair with that on the girl's personal hairbrush were released. Contradicting the commissioner's statement, the analysis found the identity of the body to be Araceli's.

In the following days and months, the brutality of the case that involved a young girl, combined with great media exposure, gave rise to national commotion and public calls for justice. Public institutions responded by releasing a series of contradictory information. For example, the police superintendent, occupying one of the highest positions in the institution's hierarchy at the time, reportedly stated: “I promise that I will reveal the names of the culprits and that there are some people from high places” (Jornal do Brasil, 1977:26). However, 4 d later, the same official, contradicting this statement, attributed the girl's murder to a poor old black man with dementia who wandered around the Praia do Suá neighbourhood, near the girl's school. The attempt to inculpate this person petered out, though, perhaps due to the subject's age and physical and mental condition as well as manifest fragility, which all spoke against him committing the crime in question.

Another significant chain of events was linked to the figure of Homero Dias, one of the lead investigators in the case. After months of investigation, Dias presented a report containing enough information to identify two people as the main suspects: Dante de Brito Michelini, known as Dantinho, and Paulo Constanteen Helal, known as Paulinho. The former came from a family linked to the international coffee trade, historically one of the central sectors of Espírito Santo's economy. The second was the son of a leading businessman in the real-estate and hotel sectors in the city of Vitória. Curiously, just after naming the two, investigator Homero Dias was removed from the case. Shortly afterwards, he was assigned to take part in the arrest of a local drug dealer known as Boca Negra. During the operation, Homero Dias was shot in the back and killed.

Accused of the crime, Boca Negra said he could not understand what had happened, since the shot had been fired by another policeman. A few days after this statement, Boca Negra was stabbed to death in jail. Dias's death was never clarified (A Gazeta, 2023). Subsequently, the police commissioner in charge of the Araceli case also asked to be removed. The investigator's family later commented that he had been threatened and offered bribes while investigating the case of Araceli (Globo Repórter, 2023:n.p.). With a third police commissioner assigned to the case, further irregularities came to light, including the fact that the conclusive report signed by Homero Dias, who had been murdered, had disappeared from the case file.

In the midst of these unfolding events, systematic efforts to disseminate wrong information to disrupt the investigations and manipulate public opinion became ever more patent. A series of disingenuous statements were made and quickly dismissed after causing the desired confusion. Araceli's parents, for example, received letters stating that the girl was alive, that she had been kidnapped to ransom and that the body found was that of another girl. Simultaneously, the father of one of the suspects named by the dead investigator came to the police station with pieces of cloth, claiming they were part of Araceli's school uniform. He further claimed to have conducted an investigation into the crime on his own and to have found this piece of cloth at the home of one of his son's friends. According to reports, this friend was classed as a “troublemaker and drug user”. Strikingly, though, this person was already dead, having died in the Santa Casa de Misericórdia hospital due to an overdose of medication, poisoning or a medical error. His death occurred on the same day that the girl's body was found, which made him a convenient suspect.

The accusation generated further distrust. The father of the “new suspect” now accused the families of those investigated of having ordered the murder of his son, claiming that they had power even in the Santa Casa de Misericórdia, where they were the providers of resources. It was later proved that the fabric presented to the police did not match Araceli's uniform (Quintino and Chagas, 2023). The attempt to incriminate the young man was now turned against Dante de Barros Michelini, the father of one of the suspects, who was “accused of contributing to the crime and using his influence to hinder the investigations” (Agência Brasil, 2023:n.p.).

In 1975, thanks in particular to the efforts of state representative Clério Falcão, a parliamentary commission of inquiry was opened in the Legislative Assembly of Vitória. That same year, Araceli, who remained unburied, was taken to the institute of forensic medicine in another state, Rio de Janeiro, in an attempt to obtain more impartial and complete cadaveric reports. The autopsy concluded that the girl had been beaten while still alive, raped and forced to take drugs. Further, it was proved that the girl had been killed by asphyxiation, in addition to all the torture. On 2 July 1976, the girl's body was returned to Espírito Santo for burial in the municipality of Serra, more than 3 years after her death.

In the same year as the burial, 1976, the first edition of Araceli, Meu Amor (Araceli, My Love) was published, a reportage novel by writer and journalist José Louzeiro, which was promptly censored at the request of the lawyers of Dantinho and his father Dante de Barros Michelini. The burial, publication and censorship of the book were events that contributed to the parliamentary commission of inquiry gaining momentum in 1976, as congressman Clério Falcão sent a letter to the then President of the Republic, General Ernesto Geisel. The letter clearly indicates that by now there was broad discontent about the entire investigation, which many perceived as flawed and tailored towards the interests of some powerful individuals that state institutions sought to protect. After pointing out a series of irregularities, such as the dismissal of the head of photography of the civil police and the disappearance of photos taken by intelligence from police archives, Falcão writes,

Many poor people have been beaten. And from time to time the newspapers in the capital of Espírito Santo report people being beaten up to get them to confess who killed Araceli. The police are trying to fabricate a murderer, but the truth is that all the people of Espírito Santo, through the testimony of the late Carlos Éboli [a renowned criminal expert], know that it wasn't a poor murderer, but more than one, and they are affluent. The people are clamouring in the streets of Vitória for justice and for the real culprits of the most heinous crime in the state of Espírito Santo not to remain on the list of the unresolved. (SECOM, 1976:n.p.)

With the collection of several important testimonies, the parliamentary commission's work strengthened the hypothesis concerning the main suspects. At the same time, Dante de Barros Michelini, the father of one of them, used his prestige vis-à-vis the police and personally participated in the “planning and execution of investigations and measures relating to the crime, supplying vehicles, fuel and other materials” (Quintino and Chagas, 2023:129).

Amid the ups and downs of the investigation and intense popular pressure, the suspects were arrested on remand in August 1977 and the father was also arrested for interfering in the investigation. All three were imprisoned until October of the same year, when their imprisonment was reviewed by a habeas corpus petition filed by their defences. The accused were tried again in 1980 and convicted at first instance. The two main suspects were sentenced to 18 years in prison, and the father of one of the suspects was sentenced to 5 years in prison due to procedural fraud. However, the lawyers of the disgruntled defendants appealed to the Espírito Santo Court of Justice, keeping the defendants free during the appeals and alleging various imperfections in the judgement, procedural defects and nullities. The appeals were only analysed in 1984, when the sentence was declared null and void and a new one was ordered. During this period, Espírito Santo was facing a serious public security situation, including an increase in cases of violence against women, which generated new social unrest. Perhaps for this reason, a new judgement was only handed down in May 1991, 18 years after the crime. Based on more than 700 pages that documented all the irregular and controversial records of the case, the judge acquitted the defendants on the grounds that there was insufficient evidence that they had committed the criminal offences. Araceli's case was concluded without conviction.

Based on official jurisdiction, the violence committed against Araceli did not have any known perpetrators. And yet, the violent event and its contested aftermath left a series of marks and traces that in themselves are revelatory. Traces can be understood as material imprints of past events that in themselves are not signs but that acquire significance once they are related to the events (Eco, 1976; cf. Mazzucchelli et al., 2014). In this sense, places where violence happened are full of traces, yet what they mean is contingent upon the forces that foster or obstruct their readability. To use these traces for analysing the necropolitical dynamics at work, we propose an understanding of power as expressed in a signature written across them. We thus approach the multiple traces in the case of Araceli as clues to the powerful forces that have conditioned the violence and its aftermath.

For example, as regards the violent event itself, the marks found on the girl's body were immediately reminiscent of many other cases of rape and murder. Likewise, the effects of corrosive acids were readily recognizable as a typical practice used by actors who are versed in committing and obfuscating lethal violence. These imprints were clearly traces of atrocious violence and attempts at obfuscation, so much so that no claim to the contrary could be sustained. However, further evidence leading investigator Homero Dias to name Paulinho and Dantinho as suspects of the crime disappeared from the case file. This can be read as pointing to a skilful act of manipulation that presupposes intimate ties among perpetrators and investigating authorities, as well as potentially further political and institutional actors. A similar set of contested traces pertained to institutional actors such as hospital employees.

While each individual event could be discounted as accidental, critical observers, such as Araceli's family or congressman Clério Falcão, read them in conjunction as indicative of a concerted regime of impunity. This critical reading can be understood as a practice of counter-forensics, one “that seek[s] to challenge state narratives that hide, obfuscate, or misrepresent exercises of state violence” (Abbott and Lally, 2025:52) – in this case, state-sanctioned violence. Specifically, counter-forensics demands the arduous task of uncovering inconvenient facts and connecting dispersed indications of violence to the potential perpetrators of the violence, often at the risk of personal attacks (Abbott and Lally, 2025:52; Ferrándiz and Robben, 2015; Huffschmid, 2015). Besides Falcão and further actors who accompanied the unfolding scenario at the time, such a counter-forensic engagement has also been carried out by contemporary investigative journalists and scholars, including Quintino and Chagas (2023) as well as, to an extent, the authors of this text.

Importantly, this engagement has been supported by more widely shared knowledge of recurrent practices of violence and obfuscation. Selecting a girl from the city's peripheries as a target for rape and murder, disposing of her corpse and using acid to eclipse the violence and eliminate identities, manipulating investigations, committing additional violence, and incriminating others – all these actions are all too familiar. Part of this knowledge is shared among those who are familiar with the pervasive phenomenon commonly referred to as “forced disappearance”. Ever since forced disappearance was first denounced in the context of Latin America's Southern Cone dictatorships, activists and relatives have pointed to systematic techniques of obfuscation and discourses of victim blaming that enable impunity (Calveiro, 1998; Claudino, 2013; Denyer Willis, 2022; Wright, 2011). Knowing that such techniques are commonly used as part of hegemonic power formations enables a connective reading of individual occurrences. For those demanding justice for Araceli, such a reading was further supported by their knowledge about the powerful social positions Dante de Brito Michelini, or Dantinho, and Paulo Constanteen Helal, or Paulinho, inhabited. Not only did Dantinho and Paulinho have the economic means to successfully appeal their conviction, but also they could count on substantial political and institutional support. Their suspected ability to arrange the deaths of Homero Dias and Boca Negra, and perhaps even the young man who died at the private Santa Casa de Misericórdia hospital, all pointed to a web of influence that spans public and private institutions, including the police, prisons and the health sector. This influence was also apparent in the close collaboration of Dantinho's father, Dante de Barros Michelini, with the police in an investigation that involved his own son.

Drawing on Giorgio Agamben (2009), we could say that what those who contested the perpetrators' impunity in the case of Araceli discerned was a signature of power across these various marks and traces. Signatures, argues Agamben, enable a particular readability, as they endow signs with reference.4 Therefore, the signature has a curious semiotic status – akin to the trace yet differently so. While the trace is an imprint that may become a sign, the signature is what makes the sign intelligible beyond isolated denotations. It refers semiotic elements to their animating force as it were, whether this force is a single actor or a complex formation. Signatures thus make the mute materiality of signs vividly readable.

Importantly, precisely what a sign's signature is – at what social, cultural, economic or technological levels it operates – is not always clear. Imagine a signed document where it is unclear whether the signature was written by hand, printed using a copier or created by artificial intelligence. Each alternative would shape the interpretation of the document's contents differently. Even if the source of the signature was known, its specific form, style or ink would be indicative of a particular material–semiotic assemblage and context of production. This implies that the style and materiality of signatures are inseparable from the contents they refer to. Conversely, approaching things through their signatures also demands an analytic openness towards multiple potential determinations of a single phenomenon.

Mitchell Dean (2012) adopts such an understanding to theorize power along the lines of Michel Foucault's analysis of power.5 Approaching power through its signatures, he argues, means reading it through the various elements and processes in which these signatures manifest. For example, rather than understanding ceremonies, inscriptions and symbols as secondary to the exercise of power, power can then be observed in “all its substantive, material, symbolic, signifying, linguistic and ceremonial manifestations” (Dean, 2012:113).6 Pertinent to our discussion, this also opens analytic pathways to “more obscure and difficult to read elements” (Dean, 2012:114).

Many elements in the case of Araceli are obscure precisely because they were purposely obfuscated. Importantly, though, the traces of obfuscation themselves bear a signature whose readability is contingent on contextual knowledge. Besides knowing about the reality of forced disappearance and the societal status of Dantinho and Paulinho, this also pertains to the language used in the context of the investigations. For example, the discursive figure that was invoked to incriminate an “old black man” (“preto velho”) who wandered around near Araceli's school bears a racialized charge of stigmatization. The expression preto velho is commonly used in Brazilian Afro-diasporic religions to denote spiritual entities pertaining to the enslaved (Hale, 1997; Rezende, 2018). At the same time, pretos velhos are also colloquially understood as “individuals whose working lives have not given them enough to rest in old age” and who therefore find themselves abandoned and waiting for assistance or left to their own devices, as an author of the Revista de Medicina once explained (Alcântara, 1924:3). In a country marked by the coloniality and racism of slavery, putting the blame on someone deprived of property, labour, income and social status can be seen as an attempt to fix the crime.

Thus, reading traces of violence and obfuscation in conjunction brings into relief, as their common signature, a multifaceted power formation inhabited and worked by various actors, techniques and discourses. Along the lines of previous engagements with lethal violence in Latin America, this formation can be qualified as “necropolitical” inasmuch as it institutionally empowers hegemonic groups to kill subaltern subjects with impunity (cf. Alves, 2014; Lopes et al., 2024; Mendiola and Vasco, 2017). However, our reading suspends any straightforward insertion of the traces that appeared in the case of Araceli into the framework of sovereign power and the logic of the exception, which have been prevalent in works on necropolitics in the wake of Agamben (1998) and Mbembe (2003; see Hutta, 2022; Mountz, 2013). While techniques of sovereignty and the exception might be at work, precisely how they manifest and are articulated with further techniques and discourses needs further interrogation. Rather than inviting this pregiven frame of interpretation, the necropolitics that emerges from assembling the dispersed traces of the crime splices together gendered violence, racist discourse, crafty techniques of obfuscation and institutional liaisons – thus constituting a “necropolitics beyond the exception” (Hutta, 2022). The role of specific materialities as bearers of traces, such as acid, documents, and the girl's very body, and the role of news media in disseminating misleading information would also merit attention.

Reading power through the signature it leaves on traces, then, enables understanding necropolitics within its context of formation and through the very elements it employs to unfold its effects. Importantly, though, the traces we have discussed become readable only as part of counter-forensic denunciations and often arduous contestations, for attempts to render the crime, its perpetrators and the victim opaque have repeatedly been challenged, from the teenager who reported the corpse to the articulations of civic groups and oppositional parliamentarians. It is these contestations that we now consider in more detail, as they enable vital insights into the workings of necropolitical power and how it can be challenged. Specifically, we will scrutinize the role that toponyms have played in naturalizing or undermining the signature of necropolitical power in Vitória.

When violent actors seek to make bodies disappear alongside any traces and witnesses of violence, they undermine public systems of accountability and effectively render themselves opaque as authors or sponsors of violence. At the same time, though, these actors leave powerful signatures in space, not only through traces of violence, but also through practices aimed at naturalizing power and stabilizing impunity. This is vividly illustrated by a public dispute that unfolded in the 2010s, after civic initiatives had proposed to rename one of the city's main avenues after Araceli. The proposal was met by strong resistance on the part of the mayor and the majority of the city council, not least because the avenue in question bears the name of an important figure in Espírito Santo's history: Dantinho's grandfather – yet another Dante Michelini. To understand the dynamics of the dispute that unfolded, it is instructive to consider this Dante Michelini's role in the context of Vitória's political economy. This also brings into relief how the Michelini family's transgenerational forging of economic and political hegemony has shaped a powerful signature whose efficacy continues to shape life and death in Vitória until the present day.

During the second half of the 20th century, the city of Vitória underwent significant economic and spatial change. Besides serving as the political–administrative seat of 1 of Brazil's 27 federal units, Vitória has also played a crucial role in the country's agricultural production and industry, especially coffee. In addition, the federal government chose the Vitória metropolitan region as an outlet for one of the world's largest iron ore exploration areas in the world, located in the neighbouring state of Minas Gerais. This decision reinforced the city as a nexus in national logistics and intensified industrial expansion and urbanization. In this process of growth and transformation, Vitória saw the construction of a large port and ore processing complex. In addition, the airport was turned into an international hub, and the city expanded, accompanied by a large-scale waterfront urbanization project. These changes not only remodelled the city's built infrastructure, but also redefined its economic and social profile in the national and transnational context. Dante Michelini played a prominent role in this process. His influence manifested in the development of critical infrastructure as well as the promotion of urban expansion policies that helped shape modern Vitória. The association of his name with one of the city's main thoroughfares, therefore, not merely was symbolic, but also reflected his active role in Vitória's profound transformation.

How did this influence develop? A descendant of Italians, Dante Michelini was born in Minas Gerais, but his family moved to Santos, on the coast of São Paulo, where Brazil's most important port has been located since the last century. As an adult, Michelini was hired by Hard Rand, an old coffee export and import company. In 1939, his duties took him to Vitória, where he stayed for a year, looking after the company's business. In 1944, he moved permanently to Vitória with his family and took over the management of another British company, Mac Kinley, likewise involved in the import and export of coffee. At the same time, Michelini was also heavily engaged in philanthropic activities, which strengthened his political clout and deepened interdependencies among different social sectors (Pontes, 2014). Specifically, he maintained an intimate relationship with the Catholic Church. This is exemplified by his funding for the lighting of the Nossa Senhora da Penha Convent, an important pilgrimage site and tourist attraction in the state. This sponsorship reflects his commitment both to what then was the mainstream religious community and to the cultural and tourist development of the region.

Michelini's interactions with the state were also intense, especially in his collaboration with Companhia Vale do Rio Doce, one of the largest companies in the mineral extraction sector on the planet. For example, he provided large areas of land for the establishment of the Port of Tubarão, a project that would boost Brazilian exports, accelerate infrastructural development, and attract international investment to Espírito Santos's infrastructure and economy. At the same time, small farming and fishing communities as well as ceramics artisans were displaced, and mangroves and sandbanks were devastated.

Michelini, then, was not only an influential businessman, but also a key player in the economic, social and political “development” of Espírito Santo who had intimate links to both urban and rural elites as well as state actors. These various liaisons emblematically illustrate a more-than-sovereign power formation, where co-dependencies among different actors serve personal as well as racial class interests (cf. Hutta, 2019, 2022). When Dante Michelini died on 1 January 1965, aged 68, his burial involved an extensive procession through the city. This public act of veneration had notable popular appeal, derived from Michelini's image as a benefactor of Vitória's modernization and prosperity. Two years after his death, during the civilian–military dictatorship, Vitória's city council built on this image when it voted to rename one of the city's most significant avenues after Dante Michelini. From 16 January 1967 onwards, the coastal road stretching from the Camburi bridge to Tubarão Pier, formerly known as Avenida Beira-Mar, was renamed Avenida Dante Michelini.

The aim of this change of toponyms was to publicly pay tribute to an important economic and philanthropic leader of the region. This is in line with the prevalent logics of urban toponymy (Alderman and Inwood, 2013; Rose-Redwood et al., 2010; Wideman and Masuda, 2018). As Paul Claval notes, “to name places is to imbue them with culture and power” (Claval, 1999:173). It is now widely recognized that the power enacted in the naming of streets and place names is often geared towards the construction of national identities shaped by intersecting logics of class, gender, imperialism and colonialism (Azaryahu and Kook, 2002; Gronemeyer, 2016; Yeoh, 1996). In this sense, Dante Michelini embodied prevalent ideals of economic success, commitment to the region and white male leadership seen as fundamental to the city's modernization and prosperity.

At the same time, the name “Dante Michelini” also instantiates the spatial signature of an influential formation of economic, political and institutional actors that spans different generations. More than representing abstract ideals, this name has been integral to the region's necropolitics. Multiple facets of this necropolitics are brought into relief by the dispute around the proposal to rename the street once again, to Avenida Araceli Cabrera. As we argue in what follows, this dispute shows how resistant actors seek to counter the naturalization of a necropolitical signature through making other kinds of signatures appear in public space.

The use of toponyms to manifest a community's values opens up the possibility of honouring not only hegemonic actors, but also those who have fought against or died of violence and injustice borne by their own societies. As several authors have shown, this can lead to contestations where civic actors demand a different politics of spatial representation (cf. Hui, 2019; Wanjiru and Matsubara, 2017). The contestation around the attempt to turn Avenida Dante Michelini into Avenida Araceli Cabrera was particularly revealing in this regard, as the old street name corresponded to the name of one of the girl's suspected murderers. This was a clash, in other words, between conflicting positions in the local and regional power geometry. While most ruling politicians sought to preserve an untainted image of the old Dante Michelini, the majority of ordinary people were in favour of shifting memorialization to Araceli.

This positioning against the old street name was strengthened by the fact that many locals read “Avenida Dante Michelini” as referring variously to Dante de Brito or Dantinho himself. Even where the toponym was read correctly, for many, the name betokened an archetypical power arrangement, commonly referred to as coronelismo, where men of influence are endowed with virtually unrestrained power at a regional level that permits them to commit arbitrary violence with impunity.7 What added to this association was that the grandfather Michelini's power was still tangible in the present. His economic standing and his influence in political, religious and even juridical spheres were inherited by both Dante de Brito and Dantinho, as indicated in their ability to mould the pathways of criminal justice. Renaming the street, then, was about inserting into the city's semiotic fabric the name of someone who had fallen victim to the very power formation the old name indexed – and thus a different kind of signature.

The movement to rename Avenida Dante Michelini to Avenida Araceli Cabrera first gained momentum in 2000, when the Brazilian federal government chose 18 May – the date of Araceli's murder – as the National Day for Combating the Sexual Abuse and Exploitation of Children and Adolescents. This legislative act was a direct challenge to politics and criminal justice in Espírito Santo. It rekindled the mobilizations of civil society in the state and simultaneously projected the Araceli case onto the national scale.8 Over the following two decades, a series of actions ensued that focussed on changing the name of the avenue, with social media emerging as a key platform. For example, on 18 May 2013, different social movements, including the Brazilian Women's Union (UBM), and ordinary people walked along the avenue to commemorate the 40th anniversary of Araceli's death and denounce four decades of impunity. Carrying placards and chanting slogans, they demanded that the avenue be renamed in memory of the Araceli case (Fig. 2).

Figure 2Araceli's memory affirmed through the National Day for Combating the Sexual Abuse and Exploitation of Children and Adolescents (Dia Nacional de Combate ao Abuso e à Exploração Sexual de Crianças e Adolescentes) (source: Araceli Cabrera Sánchez Crespo memorial website [Facebook], 2013).

Figure 3The text on the Facebook profile dedicated to the memory of Araceli Cabrera Sánchez Crespo reads, “Make it beautiful. Protect our children and adolescents” (source: Araceli Cabrera Sánchez Crespo memorial website [Facebook], last access: 10 August 2024).

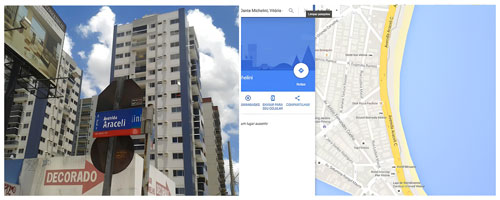

On demonstration days, a common practice among participants has been to cover street signs with stickers printed with Araceli's name, replacing that of Dante Michelini (Fig. 4). Although these stickers tend to be swiftly removed by public cleaning services in the following days, these repeated acts of resignification reflect the strategy of inserting the claim for justice directly into urban space. These street actions have also been invigorated by mobilization via the internet and social media, thus enabling broader and often less risky forms of visibilization in the face of political repression. Prominent examples are the creation of a Facebook profile in Araceli's name in 2013 (Fig. 3) and the presence of online petitions via international platforms and networks such as Change.org and Avaaz.9 Another interesting event was a cyber-attack in which a hacker changed the name of Avenida Dante Michelini to Avenida Araceli on Google Maps (Fig. 4).

Figure 4Overlay of the name Avenida Araceli on signs on Avenida Dante Michelini (left) and toponym substitution cyber-attack (right) (sources: Anarcafeministas [Facebook], 2015; Arpini, 2016/© Google Maps).

The diversity of means and media deployed to demand a change of toponymy is striking. Protesters clearly read the name “Dante Michelini” as indexing a regime of power that is behind Araceli's death and associated issues of feminicide and sexualized violence against children and adolescents. Besides being identical to one of Araceli's assumed murderers, the name also invokes a racialized and gendered semiotics that validates the status of “important man”, or even “hero”, associated with the position of landowner and entrepreneur – and by extension also a power that invisibilizes, annihilates and disappears those at whose cost this status is earned. In this sense, these protesters read the toponym as bearing a powerful signature that they want to see removed from the city's spaces.

At the same time, demonstrations, websites, street signs and artworks counter this semiotics by endowing visible presence to the memory of a girl whose body was violently disappeared and whose history has been systematically silenced. Thereby, they seek to make visible their own signature as feminists, oppositional political actors and ordinary people striving for a different kind of polis. This double move of dismounting one and inserting another signature, a recurrent strategy in struggles against feminicides and forced disappearance (Wright, 2011, 2017), is vividly exemplified in a cartoon by artist Wesley Zinek, known as Mindu. The cartoon features a smiling Araceli, who is replacing the “Avenida Dante Michelini” sign with “Avenida Araceli”, discarding the old name in the rubbish bin (Fig. 5). Here, the late Araceli comes alive herself to insert her own memory into space.10 All these interventions express space-bound variants of what Nicholas Mirzoeff (2011) calls “countervisuality”, the countering of the classifications and aesthetics through which powerful hegemonies are legitimized (cf. Beasley, 2023; Lushetich, 2018).

Figure 5The cartoon by Mindu titled “Avenida Araceli, Now!” points to the resistant potential of arts in contexts marked by necropolitics (source: Medeiros, 2023).

By producing countervisuality through various means, different civic groups and movements placed Vitória's city council under significant pressure. However, instead of meeting the demands for justice and memorial recognition, the authorities opted for an approach that reflected the continuities in the regional power formation. In 2012, a new viaduct built to improve urban circulation at the end of the disputed avenue was named the “Araceli Cabrera Crespo Viaduct”. Though the inclusion of Araceli's name in the city's toponymy can be seen as a significant achievement, this decision was also a political manoeuvre that marginalized Araceli's memory in the city's urban fabric, as it kept Dante Michelini's name on the main avenue. By relegating Araceli's name to a secondary infrastructure, which is practically an extension of Avenida Dante Michelini, the authorities tried to appease the demands for change, all the while bowing down to the conservative forces that have resisted the rewriting of historical narratives.

As, however, the demand for changing the name of the avenue continued to be strong, in 2017, the city council carried out a public consultation aimed at “finding out what the residents of Vitória think about changing the name of Avenida Dante Michelini to Araceli Cabrera Crespo” (A Gazeta online, 2017). The president of the city council said that the aim of the survey was to understand the wishes of the population, perhaps hoping this would put the popular demand to rest once and for all. He emphasized that although the poll was not an official instrument, it would serve as support for the formulation of a new bill related to the naming of public places. The poll, which quickly achieved a significant number of votes, did not go as expected though. According to the news portal A Gazeta online, 93.7 % of the votes were in favour of changing the name to Araceli Cabrera Crespo, while only 6.3 % voted to keep the current name. Despite this overwhelming result in favour of changing the name of the avenue, the mayor vetoed the change of the toponym. The city council approved his veto under dubious conditions, given the council president's earlier statement regarding the significance of the poll. Of the 13 councillors present, 7 voted in favour of the veto and only 1 in favour of changing the name, while 5 abstained. To justify their veto, some councillors stated that duplication had to be avoided. Apparently, the viaduct named after Araceli made it even more difficult to change the name of the avenue.

In a further attempt to pacify tempers, the mayor proposed the creation of a memorial, which would take the form of a large 1400 m2 mural on the viaduct itself. The Araceli Memorial was inaugurated on 4 June 2017. The ceremony was attended by local media and political authorities, including the city's mayor. Tellingly, none of Araceli's relatives were present, and there are no records in the media to indicate whether invitations were issued or whether there was any response from the relatives.

Figure 6Araceli Memorial on the base of the viaduct at the end of Avenida Dante Michelini (photographs by the authors).

The mural points to a recuperation of the protesters' countervisual impulse into a hegemonic regime of visuality. To begin with, the mural lacks any information plaque or explanation of the events depicted. Not only are the conditions of violence, the state's failures and those responsible thereby rendered invisible, but also the municipal government effectively eschews taking a public stance in favour of the victims of rape and murder. Violent acts are thereby depoliticized and naturalized as tragic events without apparent cause. Further, the bright and luminous colours, instead of transmitting the seriousness of the case, seem to evoke reconciliation and resignation, thus diluting the impetus for changes in the power relations that support ongoing violence and impede justice. The morphology features flowers, animals and angelic figures as well as smiling children reminiscent of cartoons, further contributing to this effect. Likewise, the emotions displayed on the children's, angels' and animals' faces include happiness, as well as hints of sadness or melancholy, but exclude, for example, anger or indignation. This serves to embellish the atrocity, so to speak, thus further obfuscating the event, its circumstances and its consequences.

The mural therefore, while recognizing the atrocity-cum-tragedy, leaves a necropolitical signature on the very image of Araceli. By aestheticizing the violence and its aftermath, public space is co-opted to naturalize violence while diverting attention away from structural impunity and diluting demands for justice and meaningful change. In this way, Vitória's city hall seems to have cunningly imposed a full stop on the case.

If necropolitics works through elimination and disappearance, we have argued, it also leaves traces that bear its signature. This signature manifests through physical marks on bodies and explicit references, such as street names, through implicit appraisals as expressed in ceremonies, as well as through fragmentary indications of acts of obfuscation. Approaching necropolitics through its signature thus extends the space-sensitive study of necropolitics in several ways. In relation to the performative staging of sovereignty as a power technology, it widens the view beyond spectacular killings and exemplary punishment to the use of monuments and the naming of streets (cf. Yanık and Hisarlıoğlu, 2019). Moreover, beyond the spectacular staging of sovereign power, the hiding and obfuscation of violence can also be approached as a technology that bears the signature of necropolitics (cf. Hutta, 2025).

At a methodological level, an engagement with the signature of necropolitics connects to work on counter-forensics that emphasizes the arduous task of tracing fragmentary imprints of violence scattered across space back to powerful actors, discourses and institutional arrangements. Importantly, such tracing also enables a mode of analysis that suspends the direct application of any fixed template of power and instead makes necropolitical strategies and dynamics understandable within the very context in which they operate. As such, the killing of Araceli Cabrera Crespo and its obfuscation were enabled not by a generic logic of sovereign power so much as by a confluence of situated elements including hegemonic networks of political and economic actors, naturalized violence against women and children, and racist discourse, which together arguably constitute a “necropolitics beyond the exception” (Hutta, 2022; cf. Rodrigues, 2021).

Finally, as the protests around Avenida Dante Michelini have indicated, how necropolitics is mobilized as well as challenged becomes especially apparent in contestations around signatures in urban space. Specifically, we have read the mural featuring Araceli's happy face and all her angelic accessories as a paradoxical mark or scar engraved on the urban landscape as a result of long-term struggles for justice. While the mural's function is mainly one of appeasement that serves hegemonic actors, it carries the traces of another signature as well. This is because, as some of our images have shown, Araceli's representation as a beautiful girl emerged from the protests before it was used for the mural. In the context of these protests, this representation has acted as a reminder of the beautiful life that was destroyed, and it was meant to give back some dignity to a girl whose public image has been shaped by photographs that show her burnt and corroded corpse. This other signature is shaped by local actors such as Araceli's family and oppositional politicians as well as by wider feminist movements or authors and artists from other places.

The contestation around urban toponymy galvanized mobilizations that had ramifications on the level of national legislation, thus signalling the potential of unmaking necropolitics through its spatial mechanisms. Against this backdrop, state representative Falcão's 1976 letter to the president was prescient, as it ended thus:

The blood of the beautiful girl Araceli stains the faces of the people of Espírito Santo as long as they know that her executioners continue to parade on motorbikes and in luxury cars through the streets of Vitória. And as long as impunity persists, an entire city will be in mourning. (SECOM, 1976:n.p.)

In Falcão's image, the atrocious death of the girl as symbolized by her spilled blood marks the very inhabitants of Espírito Santo, staining their faces that are confronted daily with parades of patriarchal power. These death marks, the deputy asserts, will trouble the entire city “as long as impunity persists”. Where death marks traverse the city, then, indexing what is supposed to remain hidden, neither subaltern nor hegemonic actors are at rest.

The research is based on publicly accessible historical documents and journalistic sources. Primary materials were accessed through the Public Archive of the State of Espírito Santo. Secondary sources, such as newspaper articles related to the case, were accessed via the Brazilian Digital Hemeroteca. All sources consulted are cited in the article. No proprietary or restricted data were used.

IMMR was responsible for the overall formulation of the study, including the definition of the main objectives. He participated in the development of the theory and the methodological design, carried out documentary research and research in the digital archives, and made a substantive contribution to the analysis and initial writing of the manuscript. PBT carried out the fieldwork in physical and digital archives in the city of Vitória, including in photographic archives, and was responsible for the creation of the visual representations as well as for systematizing the empirical material. She also participated in the analysis and the final revision and editing of the text. JSH played a key role in the conceptualization of the theoretical argument, in writing the corresponding parts of the initial draft, and in editing the manuscript and revising it after review. All three authors participated in the interpretation of the results and approved the final version of the paper.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a guest member of the editorial board of Geographica Helvetica for the theme issue “Special edition Social Geography: Geographies of killing and letting die”. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

The authors would like to thank those who have refused to let the memory of Araceli fade from the city of Vitória. We are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers and to Lucas Pohl for their insightful comments on earlier drafts.

Paloma Barcelos Teixeira received financial support for the research through the CAPES social demand grant, process no. 88887.840216/2023-00.

This paper was edited by Lucas Pohl and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Abbott, B. and Lally, N.: Counter-forensics and the geographies of images, Environ. Plan. D, 43, 51–69, https://doi.org/10.1177/02637758241274646, 2025.

Agamben, G.: Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, Stanford University Press, Palo Alto, ISBN 9780804732185, 1998.

Agamben, G.: The Signature of All Things: on Method, Zone Books, New York, ISBN 9781945861000, 2009.

A Gazeta: Caso Araceli comove Vitória que exige justiça, 25 May 1973a.

A Gazeta: Corpo de menina encontrado não é de Araceli, 26 May 1973b.

A Gazeta: Caso Araceli: a menina que o Brasil não pode esquecer, https://www.agazeta.com.br/es/cotidiano/caso-araceli-a-menina-que-o-brasil-nao-pode-esquecer-0523 (last access: 30 May 2025), 20 May 2023.

A Gazeta online: Câmara abre consulta para mudar nome de avenida para Araceli, https://www.gazetaonline.com.br/noticias/cidades/2017/06/camara-abre-consulta-para-mudar-nome-de-avenida-para-araceli-014061996.html (last access: 1 June 2023, no longer available online), 2 June 2017.

Agência Brasil: Após 50 anos, morte da menina Araceli é tema de livro investigativo, https://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/direitos-humanos/noticia/2023-05/apos-50-anos-morte-da-menina-araceli-e-tema-de-livro-investigativo (last access: 20 October 2024), 18 June 2023.

Alcântara, P. d.: Um problema médico social, Revista de Medicina, 6, 1–5, https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1679-9836.v6i34/35p1-5, 1924.

Alderman, D. H. and Inwood, J.: Street naming and the politics of belonging: spatial injustices in the toponymic commemoration of Martin Luther King Jr., Soc. Cult. Geogr., 14, 211–233, https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2012.754488, 2013.

Alves, J. A.: From necropolis to blackpolis: necropolitical governance and black spatial praxis in São Paulo, Brazil, Antipode, 46, 323–339, https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12055, 2014.

Alves, J. A.: The Anti-Black City: Police Terror and Black Urban Life in Brazil, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctt20h6vpx, 2018.

Anarcafeministas [Facebook]: Image posted at https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=384540671727073 (last access: 5 November 2024), 25 January 2015.

Araceli Cabrera Sánchez Crespo memorial website [Facebook]: Image posted at https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=205306536283964 (last access: 5 November 2024), 26 May 2013.

Araceli Cabrera Sánchez Crespo memorial website [Facebook]: https://www.facebook.com/AraceliCabreraSanchezCrespo, last access: 5 November 2024.

Araújo, F. A.: Não tem corpo, não tem crime: notas socioantropológicas sobre o ato de fazer desaparecer corpos, Horiz. Antropol., 22, 37–64, https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-71832016000200002, 2016.

Arpini, N.: Araceli dá nome a trecho da Av. Dante Michelini no Google Maps, G1 ES, https://g1.globo.com/espirito-santo/noticia/2016/06/araceli-da-nome-trecho-da-av-dante-michelini-no-google-maps.html (last access: 5 November 2024), 2 June 2016.

Azaryahu, M. and Kook, R.: Mapping the nation: street names and Arab-Palestinian identity: Three case studies, Nations Natl., 8, 195–213, https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8219.00046, 2002.

Beasley, M.: Performance, Art, and Politics in the African Diaspora: Necropolitics and the Black Body, Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429028489, 2023.

Calveiro, P.: Poder y Desaparición: Los campos de Concentración en Argentina, Colihue, Buenos Aires, ISBN 950-581-185-3, 1998.

Campos, C. H. d.: Feminicídio no Brasil: uma análise crítico-feminista, Sistema Penal e Violência, 7, 103–115, https://doi.org/10.15448/2177-6784.2015.1.20275, 2015.

Carvalho, J. M. d.: Mandonismo, coronelismo, clientelismo: uma discussão conceitual, Dados, 40, 2, https://doi.org/10.1590/S0011-52581997000200003, 1997.

Claudino, M. R.: Mortos Sem Sepultura: o Desaparecimento de Pessoas e seus Desdobramentos, Palavra com Editora, Florianópolis, ISBN 978-8564034075, 2013.

Claval, P.: La Geografía Cultural, Eudeba, Buenos Aires, ISBN 9789502309217, 1999.

Davis, A. Y.: Women, Race & Class, Random House, New York, ISBN 0394510399, 1981.

Dean, M.: The signature of power, Journal of Political Power, 5, 101–117, https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2012.659864, 2012.

Denyer Willis, G.: Keep the Bones Alive: Missing People and the Search for Life in Brazil, University of California Press, Oakland, https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520388536, 2022.

Eco, U.: A Theory of Semiotics, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, ISBN 0253359554, 1976.

Eichen, J. R.: Cheapness and (labor-)power: The role of early modern Brazilian sugar plantations in the racializing Capitalocene, Environ. Plan. D, 38, 35–52, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818798035, 2020.

Ferrándiz, F. and Robben, A. C. G. M. (Eds.): Necropolitics: Mass Graves and Exhumations in the Age of Human Rights, University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, ISBN 9780812291322, 2015.

Frías, S. M.: Femicide and feminicide in Mexico: patterns and trends in indigenous and non-indigenous regions, Fem. Criminol., 18, 3–23, https://doi.org/10.1177/15570851211029377, 2023.

Gambetta, V.: Dificultades y desafíos para investigar el femicidio en Latinoamérica, Rev. Lat. Metodol. Cienc. Soc., 12, 115, https://doi.org/10.24215/18537863e115, 2022.

Globo Repórter: Relembre caso Araceli, criança raptada, drogada, estuprada e morta, Espírito Santo, https://g1.globo.com/es/espirito-santo/noticia/2023/05/18/relembre-caso-araceli-crianca-raptada-drogada-estuprada-morta-es.ghtml (last access: 28 October 2024), 18 May 2023.

Gronemeyer, S.: The linguistics of toponymy in Maya hieroglyphic writing, in: Places of Power and Memory in Mesoamerica's Past and Present: How Sites, Toponyms and Landscapes Shape History and Remembrance, edited by: Graña-Behrens, D., Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut/Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin, 85–122, ISBN 978-3-7861-2766-6, 2016.

Hagerty, A.: Still Life with Bones: Genocide, Forensics, and What Remains, The Crown Publishing Group, New York, ISBN 9780593443149, 2023.

Hale, L. L.: Preto velho: resistance, redemption, and engendered representations of slavery in a Brazilian possession-trance religion, Am. Ethnol., 24, 392–414, 1997.

Hartman, S. V.: Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America, Oxford University Press, New York, ISBN 0195089847, 1997.

Huffschmid, A.: Knochenarbeit: Wider den Mythos des Verschwindens – Forensische Anthropologie als subversive Praxis, in: TerrorZones: Gewalt und Gegenwehr in Lateinamerika, edited by: Huffschmid, A., Vogel, W.-D., Heidhues, N., and Krämer, M., Assoziation A, Berlin, Hamburg, 60–75, ISBN 9783862414475, 2015.

Hui, D. L. H.: Geopolitics of toponymic inscription in Taiwan: toponymic hegemony, politicking and resistance, Geopolitics, 24, 916–943, https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2017.1413644, 2019.

Hutta, J. S.: From sovereignty to technologies of dependency: Rethinking the power relations supporting violence in Brazil, Polit. Geogr., 69, 65–76, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.11.008, 2019.

Hutta, J. S.: Necropolitics beyond the exception: Parapolicing, milícia urbanism, and the assassination of Marielle Franco in Rio de Janeiro, Antipode, 54, 1829–1858, https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12866, 2022.

Hutta, J. S.: Necropolitics and geography, in: Oxford Bibliographies: Geography, edited by: Warf, B., Oxford University Press, https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/9780199874002-0289, 2025.

Hutta, J. S.: Hide and rule: Accumulation by disappearance and necro-periurbanization in Brazil, T. I. Brit. Geogr., e70022, https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.70022, 2025.

Jornal do Brasil: Possível culpado pelo brutal assassinato de Araceli, 16 February 1977.

Lagarde, M.: Identidad de género y derechos humanos: la construcción de las humanas, VII Curso de Verano: Educación, Democracia y Nueva Ciudadanía, Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes, http://www.derechoshumanos.unlp.edu.ar/assets/files/documentos/identidad-de-genero-y-derechos-humanos-la-construccion-de-las-humanas.pdf (last access: 13 August 2025), 1997.

Lagarde, M.: Del femicidio al feminicidio, Rev. Psicoanálisis, 6, 216–225, 2006.

Lopes, F. R., Toneli, M. J. F., and Oliveira, J. M. de: Necropolítica candiru: corpo trans devorado na Amazônia, Revista de Antropologia, 15, 257–277, 2024.

Louzeiro, J.: Arceli, Meu Amor, Editora Prumo, São Paulo, ISBN 978-8579272370, 1976.

Lushetich, N. (Ed.): The Aesthetics of Necropolitics, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 9781786606860, 2018.

Mazzucchelli, F., van der Laarse, R., and Reijnen, C.: Introduction: traces of terror, signs of trauma, Versus – Quaderni di studi semiotici, 3–19, 2014.

Mbembe, A.: Necropolitics, Public Culture, 15, 11–40, https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-15-1-11, 2003.

Medeiros, M.: Avenida Araceli, já!, Século Diário, https://www.seculodiario.com.br/socioeconomicas/avenida-araceli-ja/ (last access: 5 November 2024), 18 May 2023.

Mendiola, I. and Vasco, P.: De la biopolítica a la necropolítica: la vida expuesta a la muerte, Eikasia Rev. Filos., 75, 219–248, 2017.

Mirzoeff, N.: The Right to Look: a Counterhistory of Visuality, Duke University Press, Durham, NC, https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822393726, 2011.

Mountz, A.: Political geography I: reconfiguring geographies of sovereignty, Prog. Hum. Geog., 37, 829–841, https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513479076, 2013.

Navaro, Y.: The aftermath of mass violence: A negative methodology, Annu. Rev. Anthropol., 49, 161–173, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-010220-075549, 2020.

Olamendi, P.: Feminicidio en México, Instituto Nacional de las Mujeres, https://centrohumanista.edu.mx/biblioteca/items/show/504 (last access: 13 August 2025), 2016.

Plath, S.: Three Women: a Monologue for Three Voices, Turret Books, London, 1968.

Pontes, R.: Avenida Dante Micheline, Es Brasil, https://esbrasil.com.br/endereco-da-historia-dante-michelini/ (last access: 14 September 2024), 1 August 2014.

Quintino, F. and Chagas, K.: O Caso Araceli: Mistérios, Abusos e Impunidade, Alameda, São Paulo, 2023.

Rezende, L. L.: Enxergando os mortos com os ouvidos: a reelaboração da memória da escravidão por meio da figura umbandista dos pretos-velhos, Afro-Ásia, 57, 55–80, https://doi.org/10.9771/aa.v0i57.23442, 2018.

Rodrigues, E. D. O.: Necropolítica: Uma pequena ressalva crítica à luz das lógicas do “arrego”, Dilemas – Rev. Est. Conflito e Controle, 14, 189–218, https://doi.org/10.17648/dilemas.v14n1.30184, 2021.

Rose-Redwood, R., Alderman, D., and Azaryahu, M.: Geographies of toponymic inscription: new directions in critical place-name studies, Prog. Hum. Geog., 34, 453–470, https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132509351042, 2010.

Ruette-Orihuela, K., Gough, K. V., Vélez-Torres, I., and Martínez Terreros, C. P.: Necropolitics, peacebuilding and racialized violence: The elimination of indigenous leaders in Colombia, Polit. Geogr., 105, 102934, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2023.102934, 2023.

Sahraoui, N.: The gendered necropolitics of migration control in a French postcolonial periphery, Migration and Society, 7, 138–152, https://doi.org/10.3167/arms.2024.0701OF2, 2024.

SECOM: Deputado Clério Falcão, Vitória, reference code: BR ESAPEES EA.15.84, 1975–1979, Secretaria da Comunicação Social, Public Archive of the State of Espírito Santo, Vitória, Brazil, call number EA. 0981, 1976.

Segato, R. L.: Patriarchy from margin to center: discipline, territoriality, and cruelty in the apocalyptic phase of capital, S. Atl. Q., 115, 615–624, https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-3608675, 2016.

Smith, C. A.: Strange fruit: Brazil, necropolitics, and the transnational resonance of torture and death, Souls, 15, 177–198, https://doi.org/10.1080/10999949.2013.838858, 2013.

Smith, C. A.: Facing the dragon: Black mothering, sequelae, and gendered necropolitics in the Americas, Transforming Anthropology, 24, 31–48, https://doi.org/10.1111/traa.12055, 2016a.

Smith, C. A.: Afro-Paradise: Blackness, Violence, and Performance in Brazil, University of Illinois Press, Urbana, https://doi.org/10.5406/illinois/9780252039935.001.0001, 2016b.

Souza, M. L. d.: “Sacrifice zone”: The environment-territory-place of disposable lives, Community Dev. J., 56, 220–243, https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsaa042, 2021.

Tornel, C.: Development as terracide: Sacrifice zones and extractivism as state policy in Mexico, Globalizations, https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2024.2424075, online first, 2024.

Verdery, K.: The Political Lives of Dead Bodies: Reburial and Postsocialist Change, Columbia University Press, ISBN 9780231112314, 1999.

Wanjiru, M. W. and Matsubara, K.: Slum toponymy in Nairobi, Kenya: a case study analysis of Kibera, Mathare and Mukuru, Urban and Regional Planning Review, 4, 21–44, https://doi.org/10.14398/urpr.4.21, 2017.

Wideman, T. J. and Masuda, J. R.: Assembling “Japantown”? A critical toponymy of urban dispossession in Vancouver, Canada, Urban Geogr., 39, 493–518, https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1360038, 2018.

Wright, M. W.: Necropolitics, narcopolitics, and femicide: gendered violence on the Mexico-U.S. border, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 36, 707–731, https://doi.org/10.1086/657496, 2011.

Wright, M. W.: Epistemological ignorances and fighting for the disappeared: lessons from Mexico, Antipode, 49, 249–269, https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12244, 2017.

Yanık, L. K. and Hisarlıoğlu, F.: “They wrote history with their bodies”: Necrogeopolitics, Necropolitical Spaces and the Everyday Spatial Politics of Death in Turkey, in: Turkey's Necropolitical Laboratory: Democracy, Violence and Resistance, edited by: Bargu, B., Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 46–70, https://doi.org/10.3366/edinburgh/9781474450263.001.0001, 2019.

Yeoh, B.: Street-naming and nation building: toponymic inscriptions of nationhood in Singapore, Area, 28, 298–307, 1996.

Zaragocin, S.: Gendered geographies of elimination: decolonial feminist geographies in Latin American settler contexts, Antipode, 51, 373–392, https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12454, 2019.

For example, the Latin American Feminicide Map (MLP), which is a panel created by various organizations dedicated to combating gender violence in Latin America, recorded 4599 killings of women in the region in 2023 alone, of which 1706 occurred in Brazil. On the problem of underreporting and further methodological issues, see Gambetta (2022).

Our analysis is mainly based on material that one of the authors, Paloma Barcelos Teixeira, who resides in Vitória, accessed through the Public Archive of the State of Espírito Santo. Primary documents related to the case were consulted, such as the parliamentary dossier of Deputy Clério Falcão. Moreover, since the crime generated public debate across Brazil, we analysed several of the journalistic sources that have narrated the events, which we accessed through the Brazilian Digital Hemeroteca (newspaper library).

All translations of Portuguese and Spanish sources are by the authors.

Following early-modern philosopher Jakob Böhme, Agamben posits that the signature “does not coincide with the sign, but is what makes the sign intelligible” (Agamben, 2009:2).

We bracket Dean's discussion of the signature of the concept of power and instead focus on the implications he draws for analysing power relations.

“In this sense”, Dean notes, “power relations do not have a substance but can only be known through their substances or, quite possibly, through their signatures that mark these substances” (Dean, 2012:113).

The term derives from the title of “coronel” that select landowners and other men of influence received during the First Republic, endowing them with considerable political power (see Carvalho, 1997; Hutta, 2019).

Likewise, the National Plan for Women's Policies (PNPM), drawn up in 2004 on the basis of the First National Conference on Women's Policies, boosted recognition of the issue.

See the websites of Change.org, available at https://www.change.org/p/vitoriaonline-casagrande-es-governoes-queremos-a-avenida-araceli-uma-mudança-necessária-em-vitória-es-avenidaaraceli-façabonito-18demaio (last access: 8 August 2024) and Avaaz at https://secure.avaaz.org/community_petitions/po/Alteracao_do_nome_da_avenida_Dante_Micheline_para_Araceli_Cabrera/ (last access 10 August 2024).

To draw from Verdery (1999), we might say that the political life of the dead body assumes a vivid shape here.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- A killing without killers

- Necropolitics through signatures of power

- Toponymy as signature: the case of Dante Michelini

- Toponymic contestations

- Final considerations

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- A killing without killers

- Necropolitics through signatures of power

- Toponymy as signature: the case of Dante Michelini

- Toponymic contestations

- Final considerations

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References