the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The “inhabitant footprints” of second home owners in Alpine resort communities: anyone at home?

Quentin Benoît Guillaume Drouet

Second homes are often seen as a driver of depopulation in Alpine tourist areas. However, accurately estimating demographic trends in tourist areas is challenging, as permanent residents, seasonal workers, and second home owners often adopt multilocal living patterns that vary with the seasons. We propose to reconsider the binary distinction between main and second homes which is usually monitored by conventional census data. Based on a post-pandemic survey of 1181 respondents from eight Alpine winter sports resorts (France, Switzerland, Italy, Austria, Slovenia), we introduce an “inhabitant footprint” approach. This framework examines dwelling and rental practices, habits, and second home owners' interactions with Alpine resort communities. The contribution of second home owners to year-round living dynamics varies depending on age, the geographical distribution of owners' homes, accommodation characteristics, and the specific context of each resort. Future research could extend this approach to all resident groups to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the year-round living patterns in Alpine tourist areas.

- Article

(2977 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(506 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Over the past decade, public authorities have grown concerned about maintaining the year-round residential dynamics in Alpine tourism areas as several municipalities face a demographic decline (Gauchon, 2019). The expansion of second homes is widely perceived by public authorities as creating competition in the housing market with first home buyers (Gallent and Tewdwr-Jones, 2000; Marjavaara, 2007; Roca, 2013). Previous research has highlighted the rising property prices (Rainer and Steiner, 2025) and residential migration flows in Alpine tourism areas, which may be influenced by the growing number of second homes (André-Poyaud et al., 2010; Carrosio et al., 2019). The increase in real estate values has been further accelerated in the post-pandemic period (Skoczek et al., 2023), prompting additional tensions toward second home owners (Sertout, 2015), who are perceived as threatening the ability of permanent populations to remain in place. The actual role and the practices of the second home owners within Alpine resort communities remain poorly understood, particularly in light of evolving residential behaviours and multilocal lifestyles in Alpine tourism contexts (Elmi and Perlik, 2014).

The discrepancies in the data quality of demographic censuses and second homes in tourist areas further reflect the complexity of inhabiting practices (Drouet and Koderman, 2023). The binary paradigm used by statistical offices and local authorities, such as “permanent” vs. “second” homes, fails to capture the fluid and hybrid relationships that residents have with their living spaces and different homes (Bausch, 2017). These oversimplified classifications hide the nuances with which second home owners inhabit and interact with places, particularly in tourism-driven destinations. There is a crucial need for new indicators and methodological approaches that more accurately show the diversity of residents and their contribution to living dynamics of local communities. This is especially important for regions experiencing demographic decline and growing tensions surrounding residency status. Building on this perspective, the paper proposes the concept of “inhabitant footprints” to approach second home ownership not only as a property status but also as patterns of inhabiting practices. We designed a framework to better capture the multiple ways in which second home owners interact with, contribute to, or remain detached from the socio-spatial fabric of tourism-driven communities.

The Alps offer a unique context to explore these dynamics. With their diverse cultural and legal contexts and a high concentration of second homes tied to leisure activities, the ski resort areas are emblematic of the challenges in balancing seasonal tourism with the maintenance of year-round communities. Because those municipalities depend on a seasonal economy, inhabiting practices often transcend conventional categories, such as “permanent” or “second homes” (Urbain, 2002). In such contexts, marked by strong seasonality, there is a pressing need to revisit how local populations and second home owners are conceptualised and monitored (Müller and Hall, 2003; Bausch, 2017). Therefore, this paper responds to this gap by addressing the following questions:

-

Do second homes appear in census data analysis as direct competitors to the permanent population in Alpine ski resort communities?

-

How can an empirical approach and indicators, grounded in epistemological insights into inhabiting practices, enhance our understanding of the interactions between second homes owners and ski resort communities?

-

What factors can explain the inhabiting practices of second home owners within ski resort communities in the Alps?

To address these questions, this paper examines census data and introduces the concept of “inhabitant footprints”, a new approach for capturing the social and spatial practices of residents. This concept builds upon previous research (Lazzarotti, 2006; Back, 2020) and is further explained in the following section to position our study within the existing literature. Within the scope of this research, “inhabitant footprints” refer to the interactions of residents with the areas studied and with one another in the area. The “inhabitant footprints” encompass a range of indicators such as administrative status, physical presence, local interactions, use of local services, social integration, economic interactions, place attachment, and engagement in associations and political activities. By applying this framework to Alpine ski resort communities, the paper aims to offer new insights into the complex and often ambiguous realities of inhabiting tourism-driven communities with a high share of second homes. To inform the indicators of the “inhabitant footprint” approach, we conducted a survey of second home owners in French, Swiss, Austrian, Italian, and Slovenian resort municipalities (1181 respondents on average) with high shares of second homes and exposed to strong real estate pressures and seasonality to put trends into perspective in different contexts. Germany was not included in the study, as the national census data on second homes were not available during the research period, limiting the ability to identify relevant study areas.

This section outlines the research gap that this paper aims to address, building on previous work on second home owners, multilocal dwellers, and permanent populations. The limitations of census data in tourism areas, along with the epistemological considerations of what it means to live, dwell, or inhabit a place, led us to develop a quantitative empirical approach.

2.1 Second homes owners and permanent populations in the Alps: insights from multilocal studies

Second homes in tourism destinations have been the subject of long-standing research, primarily approached from economic, environmental, and social perspectives (Coppock, 1977; Hall and Müller, 2004; Paris, 2010; Roca, 2013). In the Alpine arc, second homes have become a central concern for local authorities. Their development is seen as affecting both housing affordability and over-utilisation of the built environment (Barrioz, 2020; Carrosio et al., 2019). These dwellings often remain empty for large parts of the year and are perceived as displacing permanent residents and undermining the dynamics of year-round communities (Marcelpoil and François, 2009; Genevray, 2015). However, Bachimon et al. (2017) observed that “absentee” owners represent a very small minority in the Pyrénées Catalanes Regional Natural Park. Some authors (Coppock, 1977; Hall and Müller, 2004; Roca, 2013) suggest interpreting the development of second homes within broader socio-economic transformations such as widening income disparities between urban and rural areas (Perlik, 2011) and the increasing demand for residential amenities in scenic and recreational landscapes (Moss, 1994; Hall and Müller, 2004). Local stakeholders have also actively contributed to the growing number of second homes in the Alps, capitalising on the financial returns of a real estate economy embedded in tourism attractiveness (Clivaz and Nahrath, 2010; Gerber and Tanner, 2018).

While the impacts of second homes on land use, housing markets, and environmental resources have been well documented (Coppock, 1977; Roca, 2013; Meyer et al., 2022), much less is known about the actual relationships between second home owners and the Alpine ski resort municipalities in which their properties are located. In particular, the ways in which these owners participate or do not participate in the everyday social and spatial dynamics of Alpine resort communities remain underexplored. The COVID-19 pandemic has made these patterns more visible. It triggered temporary changes in mobility and residential behaviour, including increased stays in second homes, especially those near hospitals or equipped for remote work (Pitkänen et al., 2020; Czarnecki et al., 2021). These trends have further complicated the simplistic “resident vs. tourist” binary still dominant in census statistics and spatial planning frameworks.

The phenomenon of a multilocal lifestyle makes the monitoring of this residential status in statistical data even more complex. Several definitions of the multilocal lifestyle can be found in the literature. Stock (2006) uses the term “polytopic dwelling” and argues that individuals free themselves from a sedentary lifestyle by living in several places. He describes this as a geographical individualisation, in which mobility creates a spatially fragmented life and a geographically plural identity. Weichhart and Rumpolt (2015:63) define the multilocal lifestyle as the simultaneous or alternating pursuit of personal or economic interests in two or more places. Duchêne-Lacroix et al. (2013:65) focus on informal practices and define the multilocal lifestyle as a combination of formal (e.g. main and second residences) and informal (e.g. staying at friends' or parents' homes) living arrangements in several locations. Research on the multilocal lifestyle has expanded to examine different forms, e.g. families living in multiple locations due to separation (Schier et al., 2015), different workplaces (Jordan, 2008), and second homes (Bonnin and De Villanova, 1999). This lifestyle is particularly evident among second home owners who divide their time between different dwellings, whereby individuals maintain second homes in the Alps as part of a seasonal or recreational residential cycle (Elmi and Perlik, 2014). Furthermore, Cretton et al. (2020) examine a more exclusive form of multilocal lifestyle practised by socio-economic elites who rotate not only between the studied ski resort of Verbier and their primary residences but also among a global network of properties.

Beyond mobility, multilocal residents gain socio-cultural capital by building networks and participating in activities in the places where they live (Duchêne-Lacroix and Maeder, 2013). Digital technologies such as video surveillance, remote monitoring, webcams, and teleworking help owners to merge “here” and “elsewhere” (Cretton et al., 2020). Devices offer new abilities to owners that can be present in multiple residences simultaneously, increasing the use of second homes (Bachimon et al., 2017). This evolving relationship with property could further blur the boundaries between residential, tourist, and work functions (Stock, 2006; Duchêne-Lacroix et al., 2013). As a result, the status of these residents in different areas remains unclear, making it difficult to determine their main place of residence. In many countries, the multiple registration of permanent residence is not permitted, which means that multilocal lifestyle is largely invisible in administrative terms, even if it is real in practice (Bajuk Senčar, 2023). These studies underscore the diverse configurations of multilocal living practices and their interplay with the ownership and use of second homes in Alpine regions, highlighting complex spatial, social, and economic interrelations that merit further investigation.

2.2 Limitations of conventional quantitative indicators for the assessment of the year-round population in Alpine resort municipalities

A number of researchers have pointed out the challenges of determining the year-round resident population in tourist areas based solely on census or tax data (Müller and Hall, 2003; Terrier, 2009; Bausch, 2017). The variations of the presence of residents across multiple dwellings, due to the mobility of second home owners, create significant absences of part of the population in tourist areas. Over several decades, studies (Ragatz and Gelb, 1970; Müller and Hall, 2003; Adamiak et al., 2017) have highlighted the ephemeral population in tourist destinations, prompting further exploration of intermittent residential practices. Talandier introduced the “attendance rate” and applied it in a study on the French Atlantic coast. This rate is the ratio between the registered permanent population and the present population, calculated on the basis of the holiday departures of residents and the arrivals of tourists (Talandier, 2007). The attendance rate is supplemented by an indicator of seasonal fluctuations that identifies peaks in the number of visitors (Terrier, 2009; Blondy et al., 2013). However, this method has its limitations as it does not consider day trips by tourists, commuters, schoolchildren, or consumers. The study also points to inaccuracies in the estimation of tourist beds, which affects the reliability of the estimate of the total tourist population (Blondy et al., 2013).

Nordic researchers have developed an indicator called “Community Impact” (CI) based on the national census to account for the invisible population of second home residents in communities in Sweden that also use local infrastructure and planning resources (Back and Marjavaara, 2017; Slätmo et al., 2019). The CI is calculated as the ratio between the number of annual residents and the present population, with a standard assumption of three inhabitants per second home based on an average household size (Slätmo et al., 2019). However, this theoretical approach poses challenges, as the presence of owners may vary depending on the use of the second home due to changing occupancy over time, possible non-registration, rental initiatives, or lending properties to relatives. The unreliability of geostatistical data, due to complex residential behaviour, regularly prompts researchers to emphasise the need for empirical studies to refine quantitative estimates (Hall and Müller, 2018). Based on these findings, it is crucial to go beyond the binary distinction between second and permanent residences. Relying solely on the administrative status in statistical data offers a limited perspective on the contributions of second home owners and permanent residents in local living dynamics. We have therefore identified the need to develop an “inhabitant footprint” concept in continuation with previous authors (Lazzarotti, 2006; Back, 2020) to gain better understanding of the multilocal practices of second home owners and their impact on local communities of tourism destinations.

2.3 The “inhabitant footprint” approach to characterise the contribution of second home residents to local living dynamics in Alpine resort communities

In this section, we develop the concept of the “inhabitant footprint” approach, using a set of empirical indicators to measure the relationship between second home owners and local communities in municipalities that are major winter sports resorts. The concept of “inhabiting” goes beyond a definition tied to administrative boundaries. As Lazzarotti (2006) points out, there are different interpretations of the term “inhabiting”, reflecting diverse academic perspectives from anthropology, ethnology, psychology, literature, and geography. Inhabiting places encompasses a broader understanding of human engagement with the world, including emotional and affective relationships (Dardel, 1952), whether through individual or collective representation, imagination, virtual freedom, or even spirituality. Consequently, “inhabiting” is a multi-dimensional concept that can denote relationships to space that go beyond mere dwelling places, even beyond tangible, material connections. These cognitive and physical points of reference develop as the individuals co-construct with space (Lazzarotti, 2006). Gallent (2007) sees in the act of dwelling a strong social dimension that goes beyond material conditions, as dwellers engage with others and are creating a community. According to Stock, “To inhabit does not mean being on Earth or in a space, it is to engage with space” (Stock, 2012:59). The way in which humans use or consume space alters both themselves and the environment. Lazzarotti (2006) refers to this internalisation of space as a “geographical signature”.

There is close permeability between the characteristics and practices of permanent inhabitants, seasonal residents, second home dwellers, and tourists. Certain situations lead to a hybridity of the profile status that is not fixed in time. Indeed, situational changes can occur over the course of a person's life, making it difficult to classify individuals and to quantify these population categories in a destination such as the Alpine resort municipalities. It therefore seems essential to develop an empirical approach that makes it possible to collect information on the life rhythms and practices of second home owners. Consequently, we defined “inhabitant footprints” as a concept for capturing the socio-spatial practices, of residents that reflect their relationship to the community and their contribution to the local living dynamics. By using the term “inhabitant footprints”, we can avoid a categorisation of individuals and remain cautious of pluralistic views on who is an inhabitant and who is not. The concept takes into consideration the following criteria identified as relevant in the literature: administrative status (Gwiazdzinski et al., 2020; Bajuk Senčar, 2023), presence (Bourrat, 2000; Terrier, 2009; Blondy et al., 2013), socio-economic interactions (Hall and Müller, 2004; Back et al., 2024), use of daily amenities (Marjavaara, 2007), social integration (Hall and Müller, 2004; Marjavaara, 2007; Gallent, 2007, 2014), place attachment (Buttimer, 1980), and political and associative engagement (Blondy et al., 2016). Information on all these criteria was collected through surveys of second home owners to analyse the characteristics of “inhabitant footprints” and therefore their contributions to local living dynamics.

The competitive housing market between second home investors and permanent residents in mountain ski resort areas, combined with observed patterns of residential migration (André-Poyaud et al., 2010; Carrosio et al., 2019; Gauchon, 2019), prompted us to explore the implications for the permanent population. The access to affordable and available housing in these municipalities is affected by structural tension between different housing demands. Indeed, if second homes inherently acted as competitors to main residences, municipalities experiencing growth in the numbers of second homes would record consistent population decline.

To investigate this assumption, we have examined the statistical relationship between demographic trends and the expansion of second homes. National census data within the perimeter of the Alpine Convention offer a pragmatic way to conduct such an analysis. Using a cartographic approach, we compared municipal-level data on population change and the variation in second home numbers since 2012 across ski resort municipalities (Drouet, 2025b). The literature (Clivaz, 2013; Laslaz et al., 2015; Carrosio et al., 2019; Koderman, 2023) shows that ski resort municipalities generally have high shares of second homes. Based on this initial assessment, we have selected winter sports resorts to serve as case studies to use with the “inhabitant footprint” approach. This selection enables a more targeted empirical study using a quantitative survey of second home owners.

Given the diversity of ski resorts, we focused our analysis on the largest ski resort municipalities, where tourism and real estate pressure are strongest (Skoczek et al., 2023). We identified only one common GIS layer of data available across all Alpine countries about the number of ski lift towers (opensnowmap.org and contributors, 2022). We have intersected it with the municipalities' polygons (European Union, 2011) using QGIS software to identify the ski resort municipalities. We set the threshold at 50 ski lift towers to exclude municipalities with small ski areas from our selection as they are identified in the literature as being less exposed to real estate pressure (André-Poyaud et al., 2010).

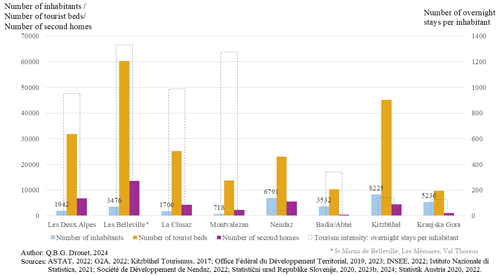

The local documentation including municipal records and publicly accessible data from tourism boards helped to identify municipalities with common features: high seasonality in tourism, strong international positioning in the tourism market, ongoing gentrification processes, a highly competitive housing market, and a local political objective of demographic growth. We considered diverse local policy measures such as second home regulations, construction of permanent housing, land use planning, taxation policies, and strategies for economic diversification to select the study areas. The final selection included eight resort municipalities across Alpine countries: four ski resort municipalities in France (Les Deux Alpes, Les Belleville, Montvalezan, La Clusaz) as part of a French-funded research project, one in Switzerland (Nendaz), one in Italy (Badia/Abtei), one in Austria (Kitzbühel), and one in Slovenia (Kranjska Gora), as shown in Fig. 1. The selected municipalities differ in terms of demographic weight, geographic context, number of second homes, tourism accommodation capacity, and tourist intensity, defined as the ratio between the number of overnight stays and the number of inhabitants.

The survey method was identified as the most suitable approach for collecting comparable data from a large sample of second home owners, especially in addressing the second and third research questions of this study. Its broader reach and time flexibility make it well suited for deployment across numerous ski resort municipalities. Moreover, the survey provides essential quantitative data to operationalise and test the empirical framework of “inhabitant footprints” developed in the theoretical section. While surveys may offer less depth in capturing personal patterns compared to interviews, their ability to generate standardised indicators at scale across diverse contexts makes them a valuable tool for investigating the inhabiting practices of second home owners.

The survey was conducted between June 2022 and June 2023 in the eight selected winter sports resort municipalities to collect data on the “inhabitant footprints” of second home owners. The purpose of the survey was to inform the previously defined set of indicators. Due to restrictions imposed by the General Data Protection Regulation, we were unable to obtain the addresses of second home owners. Given the time and budget constraints of the research, we distributed approximately 9800 paper questionnaires by hand across the eight municipalities studied. Distribution was conducted directly into households' letterboxes, with a prior focus on dwellings likely to be second homes, identified through field observation such as out-of-region vehicle licence plates, no name on the letterbox, and consistently closed shutters in the daytime. An effort was made to cover all districts or hamlets within each municipality. However, not all letterboxes could be reached. This was primarily due to a limited number of printed questionnaires and restricted physical access to certain buildings, particularly where entrance hall doors were locked.

While it is possible that some questionnaires may have been delivered to properties that were not second homes, the content and framing of the questionnaire were explicitly designed to target second home owners exclusively. The questionnaires were translated in local languages and also available in English. Owners could return them by post or scan them with the option of filling them out online through a QR code. The survey was promoted via social media, municipal newsletters (Kranjska Gora, La Clusaz, Montvalezan), and tourist office mailing lists (Les Deux Alpes). We have collected 1181 responses, albeit with considerable differences, particularly in Kitzbühel and Badia/Abtei, where the response rates were remarkably low despite high distribution numbers. These areas also have a more restrictive second home policy, which may hinder owner participation.

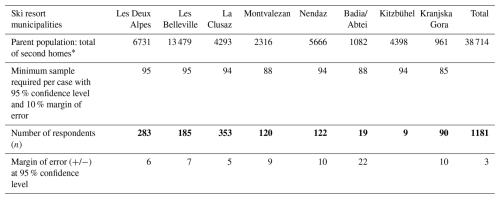

Table 1Samples of respondents to the survey by ski resort municipality.

Based on the data from the survey: Drouet (2025a). * Based on census data: INSEE (2020), Office Fédéral du Développement Territorial (2023), Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (2021), Statistik Austria (2023), Statisticni urad Republike Slovenije (2023b). The number of respondents is shown in bold to highlight the most important information in the table.

Due to the poor number of respondents in Badia/Abtei and Kitzbühel, the samples are not statistically significant and were not analysed. They are described in this paper only as an indicative trend with a specific distinction or mentioned on some of the maps. These results with no statistical value are therefore shaded in the maps.

In the questionnaire, owners provided anonymous data on the variation and cumulative presence per year in their second home. Since presence is a key indicator influencing the “inhabitant footprints” overall, we asked for the factors which are likely to have an impact on it such as the age of the householders, the distance between second home and the main residence, or the characteristics of the second home. Additionally, given the significant economic contribution of owners' expenditures and their financial relationship with the local authority, the questionnaire also sought to collect information on rental activities, tax contributions, and spending on food and local services. The data were analysed using flat sorting and cross-tabulation with Excel and RStudio software, which provided insights into the demographic characteristics of second home owners, trends in residential use, factors influencing occupancy or rental, and the second home owners' relationship with the communities.

The cross-tabulation between owners' age, the length of the journey from their main residence, and the occupancy duration of second homes was applied only to data from the French resorts to obtain a more consolidated sample and avoid potential biases arising from national socio-demographic differences. The aim was to identify key variables that may influence the occupancy rates of second homes. The survey also collected data on expenditure on food and leisure in the municipalities analysed. However, the housing-related expenditures (e.g. mortgages, insurance) were not included, as they may be very different depending on the property and not accurately reflect residents' interactions with the community.

4.1 Preliminary insight: statistical relationship between the development of second homes and demographic trends in the Alps

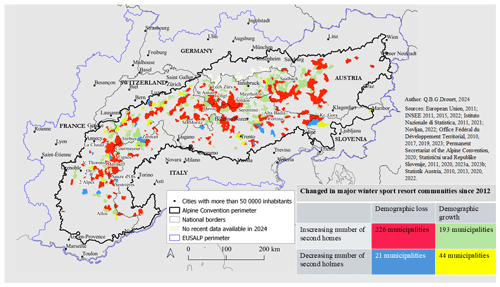

The results of the preliminary mapping analysis are presented in this subsection to assess whether second homes are represented in census data as potential competitors to the permanent population in Alpine ski resort municipalities. Figure 2 shows the spatial distribution of 478 major resort municipalities in the perimeter of the Alpine Convention. The demographic situations of the municipalities vary greatly. We have divided them into four categories corresponding to four distinct colours on the map. In view of the increase in second homes, 226 resort municipalities (47.3 % of the 478 major resort municipalities) have experienced a population loss in annual average change since 2012, while 193 (40.3 % of the 478 major resort municipalities) have recorded demographic growth. Municipalities with stable or declining numbers of second homes are also represented, albeit to a lesser extent. This map illustrates that the increase in second homes over the last decade does not necessarily lead to a decline in population. Statistical analysis using STATA software does not allow us to verify a correlation between the increase in second homes and population decline (correlation coefficient: 0.0044; p value: 0.9231).

During the development of many French resorts from the 1960s to 1980s, the number of second homes increased at the same time as the population because of the economic upturn in the municipalities (Drouet, 2025c). The demographic shifts of recent years can therefore be linked to additional factors.

Figure 2Trends in the number of second homes and demographic changes in major resort municipalities in the Alpine Convention perimeter. Data from author's calculation: Drouet (2025b).

This insight is based on the available statistical data and invited us to go further with empirical indicators to better capture demographic trends in tourist areas.

4.2 The “inhabitant footprints” of second home owners varies depending on the Alpine resorts, household situations, and housing characteristics

The results related to indicators that make up the approach to “inhabitant footprints” of second home owners are presented in detail in different subsections so that we can compare the responses of the second home owners according to the different resorts.

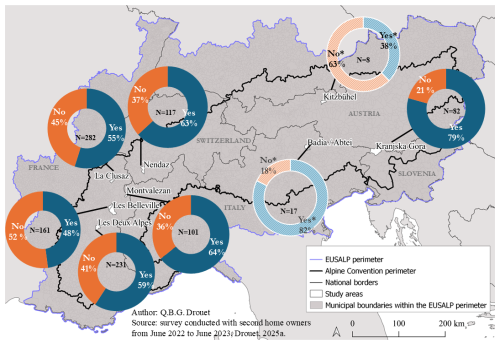

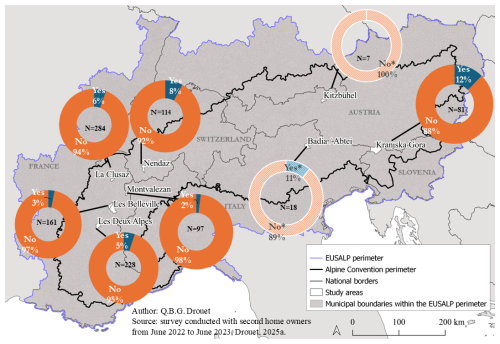

4.2.1 Indicator of administrative status

Our survey examined the proportion of households that made a switch between their second and main residence during the COVID-19 pandemic, which lasted for 1 year after the end of the crisis restrictions. The aim was to capture the decisions related to this change in terms of registration and practices, reflecting the level of porosity of the administrative status between different properties as an indicator of the “inhabitant footprint” approach. The increase in remote work for compatible positions during the COVID-19 pandemic could have contributed to new administrative arrangements regarding home status. Figure 3 shows that this phenomenon only affected a minority of residents after the pandemic. A cross-analysis revealed that larger properties were more often associated with the decision to change residence status. Furthermore, the responses do not allow any conclusions to be drawn as to whether these changes in residence will last in the long term. This would require a further survey in a few years' time.

Figure 3Question asked: have you switched your second home and your main home since the COVID-19 health crisis?

Administrative relocation rates vary between the different areas and are lowest in Montvalezan (2 %) and Les Belleville (3 %), which are further away from urban employment opportunities, compared to La Clusaz (6 %), Les Deux Alpes (5 %), Nendaz (8 %), and Kranjska Gora (12 %). A survey conducted after the COVID-19 pandemic in the Swiss resorts of Crans-Montana and Val d'Anniviers found that between 4.5 % and 5.5 % of residents converted their second home into a main residence (Gros-Balthazard et al., 2021), a rate that is lower than in our case of Nendaz. It is likely that factors such as proximity to the urban labour market and access to local amenities may influence these decisions. Nendaz, Kranjska Gora, and Badia/Abtei are particularly well located in this respect. Post-COVID-19 domicile changes were limited to a minority of households and, as such, only partially reveal residential preferences. Nonetheless, they provide limited insights into the “inhabitant footprints” of second home owners.

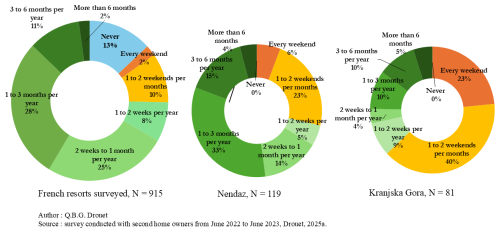

4.2.2 Indicators of presence

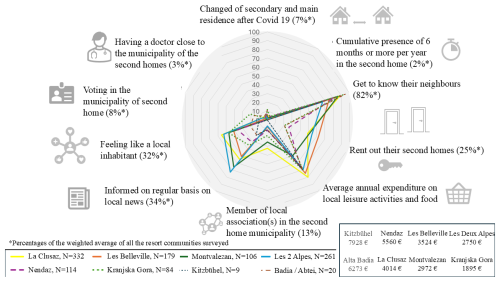

Figure 4 shows the duration and frequency of second home use by their owners, serving here as one of the indicators for the “inhabitant footprint” approach. It reflects the owners' physical presence in their property and the Alpine resort communities. In the case of the French resorts, most respondents (54 %) visited their second home of between 2 weeks and 3 months per year, but a significant proportion never visited it, which was not the case in Nendaz and Kranjska Gora. Of the 13 % of residents in French resorts who said that they never used their property, 81 % rented out their home exclusively on a short-term basis, and the number of weeks it was rented out was generally higher than that of other groups of second home owners.

Figure 4Question asked: from June 2021 to May 2022, how often did you and your family stay in your second home?

If we look at the annual median occupancy duration of second homes by adding up the median times of occupancy, rental, and lending to relatives, we get 14.5 weeks for the French resorts, 14 weeks for Nendaz, and 15.4 weeks for Kranjska Gora. Based on these median values obtained from our sample of respondents, we can therefore assume that second homes in the areas analysed are under-occupied compared to a main residence when considering for instance the French legal definition of a primary residence, which requires a minimum of 8 months (35 weeks) of occupancy per year (article 2 of the law of 6 July 1989 aimed at improving rental relationships).

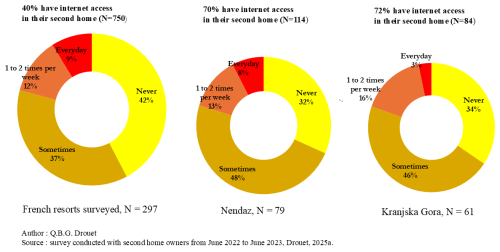

We present the results of the questionnaire on the frequency of remote working at second homes, which also indicates a desire to stay in the property and the Alpine ski community beyond leisure time, representing an aspect of the “inhabitant footprints”. Figure 5 shows that the overall trends of current remote working in second homes are the same in the French resorts, Nendaz, and Kranjska Gora. However, the proportion of householders that have never worked remotely was higher in the French cases. This can be explained by a high proportion of pensioners and a lower proportion of dwellings with internet access in the French resorts surveyed (excluding shared mobile phone connections). 40 % of the dwellings in the French resorts were connected, compared to 70 % in Nendaz and 72 % in Kranjska Gora. This effectively limits the possibility of remote working from second homes. According to our respondents, remote working would increase the presence of owners in the areas analysed by 14 % to 25 % if connectivity were improved.

To further investigate the factors that may influence the second home owners' presence, we present the results of a cross-analysis between the duration of occupancy from June 2021 to May 2022 and two variables: age group and travel time between main and second residences. This analysis helps to identify key factors that may explain variations in the presence indicator used in the “inhabitant footprint” approach. According to the Pearson χ2 test, there is a very low probability (p<0.001) of rejecting the assumption that there is no statistical relationship between age and duration of second home occupancy. Given the low p value, we tested Cramér's V on RStudio, which was V= 0.153. This indicates a small association between age group and occupancy duration, which is conventionally considered meaningful in the context of large sample sizes.

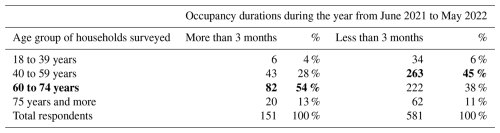

The calculation of the standard residuals shows that householders aged 60 to 74 tend to occupy their home for longer per year than householders aged 40 to 56, as shown in bold font in Table 2.

Table 2Cross-analysis between age classes and the duration of occupation of the four French resorts studied.

Test with RStudio software: Pearson χ2 = 17.04, Pr = 0.0006933 (“Pr” denotes the probability (p value) in mathematical notation). Based on the data from the survey: Drouet (2025a). The values in bold font refers to the most significant association between age groups and the duration of occupation.

The greater occupation of second homes by older owner householders has already been observed in previous studies (Atout France, 2019), but interestingly, this trend persists in winter sports resorts where physical outdoor activities are predominant.

In the French resort municipalities analysed, householders with a primary residence less than 1 h away from the second home were significantly overrepresented in terms of households with an annual occupancy of more than 3 months according to the cross-analysis and using the standard residue calculation. As can be seen in Table 3, Pearson's χ2 test shows that the probability of rejecting the assumption that there is no statistical relationship between the distance to the main residence and the duration of occupancy of the second home is very low (p<0.05).

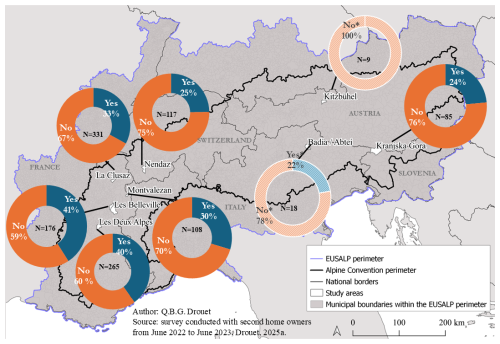

To gain a more forward-looking perspective on the evolution of presence as a key dimension of the “inhabitant footprint” approach beyond the immediate post-COVID survey period, we present results based on second home owners' estimates of their future occupancy over the coming years. Figure 6 shows that the majority of home owners intended to increase the occupancy rate of their homes, except in Les Belleville, where Table 4 indicates a significantly higher proportion of lessors. In the municipalities of Montvalezan and Nendaz, 64 % and 63 % of respondents respectively planned to visit their second home more often in the coming years. These percentages are higher than the results of the Atout France 2019 survey conducted throughout France, in which only 40 % of owners stated that they planned to visit their second home more often in the future. Some assumptions can be formulated, such as the impact of the pandemic, the impact of global warming positioning the mountains as cooler areas, or the fact that second homes in resorts will be more attractive to owners in the future than the average for mainland France.

While the majority expressed a desire to extend their stay in their second home in the future, only a minority planned to swap their primary and second home over time, confirming previous studies (Sarman and Czarnecki, 2020).

4.2.3 Indicator of socio-economic interactions

As part of our analysis of socio-economic interactions between second home owners and Alpine resort communities, we examine short-term rental activities for tourists by some owners of second homes. This indicator provides insight into their level of engagement with the local economy. In the French resorts surveyed, the median number of weeks for homes rented out by owners in 2022 was 8.1 weeks, compared to 7 weeks in the year after purchase (which varies depending on the year of purchase by households). This result is lower than the average for mainland France, which is estimated at 11.5 weeks (Atout France, 2019a:83). However, the Atout France report that led to this estimate shows that rental practices are higher in mountain areas in winter but lower in summer and much lower in the low season than in urban areas or on the coast. The comparison with the French mainland average is therefore not very representative, as it includes urban and coastal areas where rental durations are consistently higher all year round than in the mountains.

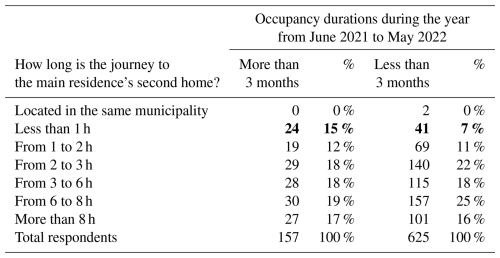

Table 3 shows the median values for each of the resorts analysed and relates them to other indicators. It helps to compare variables that might partly explain rental patterns.

Table 3Cross-analysis between the travel time from the main residence and the duration of occupation of the four French resorts analysed.

Test with RStudio software: Pearson χ2 (with simulation of the p value) = 15.09, Pr = 0.02199. Based on the data from the survey: Drouet (2025a). The values in bold font refer to the most significant association between the travel time from the main residence and the duration of occupation.

Table 4The number of weeks where the second home is rented out compared to other indicators in the resorts surveyed.

Based on the data from the survey: Drouet (2025a).

The rental period was shorter in La Clusaz (6 weeks in 2022). It increased the most in Montvalezan (from 5.5 to 7.5 weeks) between the year after the purchase of the property (not represented in this table) and the year before the survey. 42 % of respondents from French resorts explained that the rental or increase in rental duration since the year of purchase was due to a renovation of the property. 19 % attributed this to the professionalisation of rental management. The cross-analysis of the sample of French resorts shows that the number of weeks homes are rented out for is strongly related to the length of ownership and socio-professional status, with retirees generally renting out less frequently than employees. Concerns about potential property damage and the desire to maintain flexibility in the use of the residence have been cited in previous studies as key barriers to renting out (Dias et al., 2015).

Figure 7 provides an overview of the responses from the resorts surveyed regarding their rental intentions over the next 5 years. It shows clear differences between the higher rates in Les Belleville (41 %) and Les Deux Alpes (40 %) compared to Nendaz and Kranjska Gora.

On average, 38 % of second home owners in the French resorts surveyed were considering renting out more frequently in the next 5 years, compared to only 14 % in the French mainland (Atout France, 2019:108). The next subsection further analyses the socio-economic interactions by looking at the owners' expenditure.

4.2.4 General overview of the analysis of the “inhabitant footprints” of second home owners

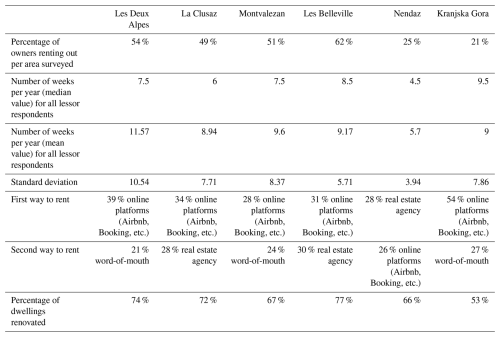

In addition to the previous findings on the administrative status (post-COVID-19 pandemic domicile changes), presence (occupancy), economic interactions (short-term rental patterns), and the role of geographic and age-related variables, the survey allowed us to identify other characteristics of second home residents that reflect their relationships with the resort community. Figure 8 shows a selection of indicators that contribute to the “inhabitant footprint” approach. However, it should be noted that the sample sizes presented from Kitzbühel and Badia/Abtei were not statistically significant.

Figure 8Selective indicators for analysing the “inhabitant footprints” of second home owners in Alpine resort communities. Based on the data from the survey: Drouet (2025a).

Firstly, the proportion of households that stayed in their second home for 6 months or longer remained very low. Only a minority switched between their second and main residence during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, the percentage of owners who regularly followed the local news was remarkably high in French resorts surveyed (58 %) and rather low in the other resorts like Nendaz (31 %), Kranjska Gora (35.7 %), Kitzbühel (22 %), and Badia/Abtei (21 %). These indicators reflect the strong attachment of owners to the community in which they have their second home, as already highlighted by Blondy et al. (2016) on the Charente-Maritime coast and by Bachimon et al. (2017) in the Pyrenees.

In all the study areas, the percentage of owners involved in associations was relatively low (13 %). As an indicator of social interaction, Fig. 7 shows a very high level of familiarity with the neighbourhood (82 % all resorts surveyed), with 92 % in Kranjska Gora and 88 % in La Clusaz. The social impact of second home ownership depends on the criteria used.

The significant proportion of owners who were renting out their property in the French municipalities (57 %) underlines their indirect contribution to the local economy, since the renters are likely spending money on local commodities. The percentage for other resorts was so low that, when all resorts are taken into account, this proportion drops to 25 %. However, the potential of the winter and summer seasons in French resorts remains underutilised, with a median value of only 8.1 weeks per year.

Food and leisure expenditures of the second home owners were compared to the estimated spending baskets of permanent residents to assess the economic contribution of second home owners for the French areas studied. On average, the economic contribution of a second home owner (Fig. 8) was found to be slightly more than half compared to the one from permanent residents in Les Deux Alpes and Montvalezan and between half and nearly equivalent in La Clusaz and Les Belleville. This assessment is based on expenditure data from an INSEE study (2020), which estimates average annual household spending in 2017 on food, leisure, and culture at approximately EUR 5202 at national level. Nevertheless, the level of expenditure varies considerably from one municipality to another, as shown in Fig. 8, reflecting differences in the local cost of living. According to a study made by Atout France, older second home owners tend to go shopping and eat out more often than younger owners, who, in contrast, make greater use of the leisure facilities (Atout France, 2019).

Our findings have shown that there is no verified correlation between the increase in second homes and population decline in Alpine ski resort communities over the last decade. This confirms a more nuanced view of the dynamics between second home owners and permanent residents (Hall and Müller, 2004). Demographic change in these areas is likely influenced by a more complex set of factors and cannot be attributed solely to the presence of second homes. While regulation is often seen as a necessary tool to manage second home development, numerous studies suggest that second homes should be viewed not as the cause of depopulation but rather as a symptom of seasonality (Drouet, 2025c) and of a profit-oriented real estate economy (Rainer and Steiner, 2025), which is gaining the upper hand over tourism development (Coppock, 1977; Clivaz, 2019; Bätzing, 2021). The dynamic is driven by broader forces, including regional income disparities, amenity migration, investment in property, and other socio-cultural factors (Marjavaara, 2007; Perlik, 2011). However, many resort communities already have a high proportion of second homes, making large-scale residential reallocation unrealistic. In addition, regulations may be limited due to the porosity of administrative residence statuses, the flexibility of residents' declarations (Borsdorf, 2013), and the interests of local players who may persist in a real estate economy (Gerber and Tanner, 2018). A study of nine traditional winter sports villages in Norway (Ericsson et al., 2024), which focused on the increase in new second home owners, highlights that local strategies to mitigate undesirable effects may be more appropriate than relying on second home regulation alone.

Rather than advocating for restrictive measures that set second home owners in opposition to permanent residents, our research has shown the role of an empirical approach to better understanding the contributions of second home owners to local dynamics. These contributions may support the stabilisation of the permanent population or foster interactions that benefit local economic and social activities. The implementation of our “inhabitant footprint” approach demonstrates that empirical indicators, grounded in the epistemological framework of inhabiting, are effective in capturing the diversity of practices and relationships between second home owners and the area studied. A comparable empirical approach conducted in Charente-Maritime, on the French coast, enabled researchers to identify the specific ways in which second home owners contribute to the local community (Blondy et al., 2016). While several survey-based studies have been conducted, they tend to focus on specific issues, such as shifts in residential practices following the COVID-19 pandemic (Czamecki et al., 2021), housing patterns (Sarman and Czarnecki, 2020), and the transformation of housing status from permanent to secondary (and vice versa) in the post-COVID context (Gros-Balthazard et al., 2021). To fully realise the potential of this approach, data collection tools must encompass second home owners, seasonal workers, and permanent residents. This inclusion would be essential for enabling meaningful comparisons that help identify distinguishing or converging patterns of inhabiting practices within areas subject to intense seasonal variations.

The significant role of second home owners as key economic contributors to the destination highlighted in our approach has also been shown by several researchers (Bourrat, 2000; Genevray, 2015). The residents can play an important role as ambassadors and investors for the destination (Bohn and De Bernardi, 2019). In the Charente-Maritime study, a significant proportion of second home owners were involved in local associations (Blondy et al., 2016), as was also observed in a similar study in Finland (Czarnecki and Rantanen, 2023). This can be seen as another way of contributing to local dynamics without being present in the area full-time. However, this finding is less pronounced in the resorts included in our survey. Most owners expressed a strong attachment to the area in which they have their second home, particularly through a sense of belonging to the community, an interest in local news, and by some participation in local elections where legally possible. These results are partly consistent with studies conducted on the Charente-Maritime coast (Blondy et al., 2016) and in the Pyrenees (Bachimon et al., 2017). Previous research highlighted that attachment to second homes can vary significantly, particularly depending on the nature and history of the property. Homes inherited or used as childhood residences, for example, often carry strong emotional ties (Toso, 2023), while in our study areas, many second homes are commercially oriented tourist rentals located in condominiums, which tend to foster weaker personal attachment. Nonetheless, some second home owners play a more active role in the local community beyond personal use. As shown by Perrot and De la Soudière (1998) and Czarnecki and Rantanen (2023), certain owners contribute to heritage preservation efforts and cultural initiatives, thereby reinforcing their presence in the social and community life. To identify these less common owner profiles, the quantitative empirical approach employed in our study is limited. Qualitative interviews may provide deeper insights into these more specific cases. Moreover, breaking down the data exclusively per variable (flat sorting, cross-tabulation) rather than by individual may affect our perception and understanding. As part of a complementary analysis, we would suggest experimenting with additional methods based on data re-aggregated at the individual level, which makes it possible to identify distinct profiles of second homes. This would allow us to put into perspective several methods for approaching the “inhabitant footprints” of second homes.

Given the importance of second home owners to tourism and the local economy and their potential to contribute to higher housing occupancy, it is crucial for local communities to explore experimental initiatives to better integrate these residents. Nevertheless, a lack of consultation with second homes owners has been highlighted in several study cases (Nordin and Marjavaara, 2012; Kietäväinen et al., 2016), even though they are directly affected by public policies. An alternative approach could involve second home owners more directly in local governance and encourage co-operation. Few studies have examined the potential outcomes of better integrating second home residents into local dynamics (Hao et al., 2013; Soszyński et al., 2017). In Finland, for example, research has been conducted into how the participation of second home owners in village development can be improved. However, it was found that the owners did not actively participate in municipal meetings, which meant that their needs could only be considered to a limited extent (Robertsson and Marjavaara, 2014; Kietäväinen et al., 2016). To achieve meaningful inclusion, significant community engagement efforts are needed to ensure that second home residents actively participate in local decision-making and understand that the destination needs their homes to remain a place to live, linked to the maintenance of services and leisure infrastructures.

This study set out to examine how second homes and their owners influence local living dynamics in Alpine ski resort communities, in light of demographic decline in some municipalities, housing market pressure, and evolving forms of inhabiting. The findings confirm that, based solely on administrative status and presence indicators, most second home owners cannot be categorised as “part-time residents” (Bachimon et al., 2017:5). The median occupancy duration including personal use, lending, and rentals remains well below 6 months annually across all study sites.

Through the statistical analysis of the survey, we were able to determine that certain characteristics of resorts, second homes, and household situations can lead to different residential behaviour. For example, the length of stay per year tends to be longer for older second home owners or if the main residence is less than an hour's drive away from the second home. A small minority of second home owners have actually become permanent residents following the COVID-19 health crisis. However, it is unclear whether these changes in residence will continue in the coming years.

The concept of “inhabitant footprints” helped in exploring the multifaceted ways in which second home owners contribute to local living beyond physical presence. These include emotional attachment to place, involvement in local initiatives, social engagement, and economic participation through local spending and rental activities. The rental patterns are particularly evident in the French case studies, where second homes have historically made a significant contribution to the development of tourist accommodation capacity (Genevray, 2015). Taken together, these findings suggest that second home owners, though not “permanent residents” in the administrative sense, play a differentiated and often meaningful role in the socio-spatial dynamics of resort communities. By incorporating indicators that reflect actual living practices, the “inhabitant footprint” approach offers a promising alternative to static population categories. This lens aligns with emerging research on multilocal lifestyles, offering a pathway to more nuanced understandings of population dynamics in Alpine resort areas. Future research could expand this approach to include other households such as full-time residents, seasonal workers, and tourists. It would enable a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of who inhabits Alpine tourism areas and how.

The data set from the survey of second home owners in the analysed winter sports resort municipalities and the author's calculations of annual variations in population and change in the number of second homes of the major Alpine ski resort municipalities, which were used for Fig. 2 in the article, are publicly available. They are available in the Nakala repository as indicated in the references of this article (https://doi.org/10.34847/NKL.92596YS1, Drouet, 2025a; https://doi.org/10.34847/NKL.CDBB2564, Drouet, 2025b).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-80-363-2025-supplement.

The author has declared that there are no competing interests.

Publisher' note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions, which helped improve this article.

This work is supported by the French National Research Agency in the framework of the “France 2030” programme (grant no. ANR-15-IDEX-0002) through LabEx ITEM and the French Ministry for Ecological Transition and Territorial Cohesion (Fonds National d'Aménagement et de Développement du Territoire).

This paper was edited by Marco Pütz and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Adamiak, C., Pitkänen, K., and Lehtonen, O.: Seasonal residence and counterurbanization: the role of second homes in population redistribution in Finland, GeoJournal, 82, 1035–1050, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-016-9727-x, 2017.

André-Poyaud, I., Duvillard S., and Loriaux A.: Les mutations foncières et immobilières au pays du Mont-Blanc entre 2001 et 2008, Revue de géographie alpine, 98-2, https://doi.org/10.4000/rga.1221, 2010.

ASTAT: Tourismusverein Alta Badia, personal communication by email on 20 February 2023 with licensing agreements, 2022.

Atout France: Résidences secondaires et développement touristique des destinations, Observations touristiques, Editions Atout France 52, 83 pp., 2019.

Bachimon, P., Derioz, P., and Vles, V.: Les intermittents du territoire: les différentes facettes de la résidence secondaire. Enquête comparative (Cerdagne 66, Vicdessos 09, Haut Ossau 64) sur le dédoublement résidentiel et son impact économique, culturel et urbanistique, Conférence à l'initiative du Parc naturel régional des Pyrénées catalanes, Palau de Cerdagne, France, 8 décembre 2017 à Palau de Cerdagne, 14 pp., 2017.

Back, A. and Marjavaara, R.: Mapping an invisible population: the uneven geography of second-home tourism, Tourism Geographies, 19, 595–611, https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1331260, 2017.

Back, A.: Footprints of an invisible population. Second-home tourism and its heterogeneous impacts on municipal planning and housing markets in Sweden, PhD Thesis, Department of Geography, Umeä Universitet, 91 pp., https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.19233.63847, 2020.

Back, A., Hane-Weijman, E., and Hoogendoorn, G.: Temporary residents and permanent jobs? Second-home tourism and job creation in the construction sector, Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 1–24, 244–267, https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2024.2372300, 2024.

Bajuk Senčar, T.: Introduction: The (In)visibility of Multi-locality in Theory and Practice, Traditiones, 52, 7–22, https://doi.org/10.3986/Traditio2023520301, 2023.

Barrioz, A.: Réinventer l'attractivité de confins dans les Alpes françaises: le défi de l'accès au logement en contexte touristique, Via Tourism Review, 18, https://doi.org/10.4000/viatourism.5977, 2020.

Bätzing, W.: Zweitwohnungen im Alpenraum. Eine selbstzerstörerische Entwicklung”, Bergauf Magazin, Mitgliedermagazin des Österreichischen Alpenvereins, 76, 70–71, 2021.

Bausch, T.: Why demography forecasts fail in tourism areas: a spatial demographic mapping of a small alpine village, Sustainable Development of Mountain Territories, 9, 45–54, https://doi.org/10.21177/1998-4502-2017-9-1-45-54, 2017.

Blondy, C., Vacher, L. and Vye, D.: L'apport de la notion de population présente dans l'analyse du peuplement littoral, Espace populations sociétés, 95–110, https://doi.org/10.4000/eps.5354, 2013.

Blondy, C., Vacher, L., and Vye, D.: Les résidents secondaires, des acteurs essentiels des systèmes touristiques littoraux français ? L'exemple de la Charente-Maritime, Territoire en mouvement, Revue de géographie et d'aménagement, 30, https://doi.org/10.4000/tem.3344, 2016.

Bohn, D. and De Bernardi, C.: The different shades of snow – An analysis of winter tourism in European regional planning and policy documents, in: Winter tourism: Trends and challenges, edited by: Pröbstl-Haider, U., Richins, H., and Türk, S.: CABI, Wallingford, UK, 47–63, https://doi.org/10.1079/9781786395207.0047, 2019.

Borsdorf, A.: Second homes in Tyrol: Growth despite regulation, Revue de Géographie alpine, Hors-Série, https://doi.org/10.4000/rga.2262, 2013.

Bourrat, Y.: La résidence secondaire. Obstacle ou tremplin au développement local?, Espaces tourisme et loisirs, 176, 16–21, 2000.

Bonnin, P. and De Villanova R.: D'une maison l'autre, parcours et mobilités résidentielles, Créaphis, Paris, pp. 371, 1999.

Buttimer, A.: Home, reach, and the sense of place, in The human experience of space and place, edited by: Buttimer, A. and Seamon, D., The human experience of space and place, St. Martin's Press, New York, USA, 166–187, ISBN 9781138924710, 1980.

Carrosio, G., Magnani, N., and Osti, G.: A mild rural gentrification driven by tourism and second homes. Cases from Italy, Sociologia urbana e rurale, 119, 29–45, https://doi.org/10.3280/SUR2019-119003, 2019.

Clivaz, C.: Acceptation de l'initiative sur les résidences secondaires. L'émergence d'un nouveau modèle de développement pour les stations de sports d'hiver suisses?, Revue de géographie alpine, Special issue, https://doi.org/10.4000/rga.1866, 2013.

Clivaz, C.: Qui gouverne en station de sports d'hiver? L'exemple de Crans-Montana dans les Alpes suisses, in: Le tourisme hivernal. Clé du succès et de développement pour les collectivités de montagne? edited by: Peypoch N. and Spindler J., L'Harmattan, Paris, France, 79–112, ISBN : 9782343187006, 2019.

Clivaz, C. and Nahrath S.: Le retour de la question foncière dans l'aménagement des stations touristiques alpines en Suisse, Revue de géographie alpine, 98, https://doi.org/10.4000/rga.1220, 2010.

Coppock, J. (Ed.): Second Homes: Curse or Blessing?, Oxford: Pergamon, London, 229 pp., ISBN 0080213715, 1977.

Cretton, V., Boscoboinik A., and Friedli A.: À l'aise, ici et ailleurs. Mobilités multirésidentielles en zone de montagne: le cas de Verbier en Suisse, Anthropologie et Sociétés, 44, 107–126, https://doi.org/10.7202/1075681ar, 2020.

Czarnecki, A. and Rantanen, M.: Second-home owners as local developers: Roles and influencing factors, Journal of Rural Studies, 97, 560–572, 2023.

Czarnecki, A., Dacko, A., and Dacko M: Changes in mobility patterns and the switching roles of second homes as a result of the first wave of COVID-19, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31, 149–167, https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.2006201, 2021.

Dardel, E.: L'Homme et la terre. Nature de la réalité géographique, Presses universitaires de France, 133 pp., ISBN 2735502007, 1952.

Dias, J. A., Correia, A., and Lîìpez, F. J. M.: The meaning of rental second homes and places: the owners' perspectives, Tourism Geographies, 17, 244–261, https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2014.959992, 2015.

Drouet, Q. B. G.: Survey with second home owners in Alpine ski resorts (Version 1), NAKALA [data set], https://doi.org/10.34847/NKL.92596YS1, 2025a.

Drouet, Q. B. G.: The annual variations in population and the change in the number of second homes of the most important ski resort municipalities in Alpine region (Version 1), NAKALA [data set], https://doi.org/10.34847/NKL.CDBB2564, 2025b.

Drouet, Q. B. G.: Year-round Living in Alpine Arc Resorts Facing High Tourism Intensity and Seasonality, Via Tourism Review, https://doi.org/10.4000/14gbs, 2025c.

Drouet, Q. B. G. and Koderman, M.: Methodological challenges in the research on second homes: lessons learned from the Alpine region, Slovenia and the Municipality of Kranjska Gora, Geografski Vestnik, 95, 33–68, https://doi.org/10.3986/GV95202, 2023.

Duchêne-Lacroix, C. and Maeder, P.: La multilocalité d'hier et d'aujourd'hui entre contraintes et ressources, vulnérabilité et résilience, in: Hier und Dort: Ressourcen und Verwundbarkeiten in multilokalen Lebenswelten, edited by: Duchêne-Lacroix, C. and Maeder, P., Société Suisse d'histoire, Basel, 8–22, ISBN 9783796529481, 2013.

Duchêne-Lacroix, C., Hilti, N., and Schad, H.: L'habiter multi-local: discussion d'un concept émergent et aperçu de sa traduction empirique en Suisse, Revue Quetelet, 1, 63–89, https://doi.org/10.14428/rqj2013.01.01.05, 2013.

Elmi, M. and Perlik, M.: From tourism to multilocal residence? Unequal transformation processes in the Dolomites area, Journal of Alpine Research, 102-3, https://doi.org/10.4000/rga.2608, 2014.

Ericsson, B., Lerfald, M., and Overvåg, K.: Second homes: from family project to tourist destination – planning and policy issues, Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2024.2332309, 2024.

European Union: Local administrative units (LAU), Eurostat, GISCO data distribution API [data set], https://gisco-services.ec.europa.eu/distribution/v2/lau/ (last access: 23 October 2025), 2011.

European Union: Eurostat NUTS3, Eurostat GISCO, Geodata, Reference data, Administrative Units/Statistical Units NUTS [data set], https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/gisco/geodata/statistical-units/territorial-units-statistics(last access: 9 October 2025), 2013.

G2A: number of beds and number of overnight stays per resort, personal communication by email on 22 September 2023 with licensing agreements, 2022.

Gauchon, C.: La montagne touristique française : une démographie en panne?, in: Des ressources et des hommes en montagne, edited by: Duma, J., CTHS, Paris, 56281–13, https://doi.org/10.4000/books.cths.5766, 2019.

Gallent, N.: Second Homes, Community and a Hierarchy of Dwelling, Area, 39, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2007.00721.x, 2007.

Gallent, N.: The Social Value of Second Homes in Rural Communities, Housing, Theory and Society, 31, 174–191, https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2013.830986, 2014.

Gallent, N. and Tewdwr-Jones, M.: Rural Second Homes in Europe. Examining Housing Supply and Planning Control, Routlegde, New York, 166 pp., ISBN 9781138706156, 2000.

Gerber, J. D. and Tanner, M. B.: The role of Alpine development regimes in the development of second homes: Preliminary lessons from Switzerland, Land Use Policy, 77, 859–870, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.09.017, 2018.

Genevray, C.: Les résidences secondaires, un enjeu majeur pour l'avenir de l'économie des stations de montagne, Espaces tourisme et loisirs, 326, 76–80, 2015.

Gros-Balthazard, M., Clivaz C., and Kebir, L.: Résidences secondaires : pratiques des résidents et stratégies des destinations en Valais ”, Présentation, Forum scientifique regiosuisse, Université de Lausanne, Suisse, 18 pp., https://regiosuisse.ch/sites/default/files/2021-09/Laurenti_ Secondary residences.pdf (last access: 9 October 2025), 2021.

Gwiazdzinski, L., Colleoni, M., Cholat, F., and Daconto, L. (Eds.): Vivere la montagna. Abitanti, attività e strategie, FrancoAngeli, Milano, Italy, https://www.ibs.it/vivere-montagna-abitanti-attivita-strategie-ebook-vari/e/9788835103998 (last access: 9 October 2025), 2020.

Hall, C. M. and Müller D. K. (Eds.): Tourism, Mobility and Second Homes. Between Elite Landscape and Common Ground”, Aspect of Tourism, 15, 320 pp., https://doi.org/10.21832/9781873150825, 2004.

Hall, C. M. and Müller, D. K. (Eds.): The Routledge Handbook of Second Home Tourism and Mobilities, Routledge, New York, 384 pp., ISBN 9781032339153, 2018.

Hao, H., Alderman, D. H., and Long, P.: Homeowner attitudes toward tourism in a mountain resort community, Tourism Geographies, 16, 270–287, https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2013.823233, 2013.

INSEE: Populations légales 2011, INSEE [data set], https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/2119747?sommaire=2119751 (last access: 9 October 2025), 2011.

INSEE: Recensement de la population. Logement en 2012, INSEE [data set], https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/2044713 (last access: 9 October 2025), 2015.

INSEE: Les ménages les plus modestes dépensent davantage pour leur logement et les plus aisés pour les transports, 203, https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/4764315 (last access: 23 October 2025), 2020.

INSEE: Populations légales 2021, INSEE [data set], https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/7728826 (last access: 23 October 2025), 2021.

INSEE: Recensement de la population. Logement et résidences principales en 2019, INSEE [data set], https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/6454268(last access: 9 October 2025), 2022.

Istituto Nazionale di Statistica: Censimento Popolazione Abitazioni, Alloggi. Abitazioni occupate da persone residenti, Abitazioni non occupate da persone residenti 2011 [data set], http://dati-censimentopopolazione.istat.it/Index.aspx?lang=it&SubSessionId=c3813463-9ff8-42f8-8c7a-0760862de603&themetreeid=16 (last access: 25 June 2025), 2011.

Istituto Nazionale di Statistica: Censimento Popolazione Abitazioni. Alloggi. Abitazioni occupate da persone residenti. Abitazioni non occupate da persone residenti 2021, Istituto Nazionale di Statistica Roma [data set], http://dati-censimentipermanenti.istat.it/?lang=it&SubSessionId=f0210256-9cff-4801-948a-a3b0bc2f27a6 (last access: 25 June 2025), 2021.

Jordan, B.: Living a Distributed Life: Multilocality and Working at a Distance, NAPA Bulletin, 30, 28–55, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4797.2008.00018.x, 2008.

Koderman, M.: Geographical characteristics of second home tourism in Slovenia-A regional overview, Geografski pregled, 49, https://doi.org/10.35666/23038950.2023.49.09, 2023.

Kietäväinen, A., Rinne, J., Paloniemi, R., and Tuulentie, S.: Participation of second home owners and permanent residents in local decision making: The case of a rural village in Finland, Fennia – International Journal of Geography, 194, 152–167, https://doi.org/10.11143/55485, 2016.

Kitzbühel Tourismus: Facts and figures, 3 pp., https://www.newsroom.pr/at/pressemappen/pressemappe.php?page=news::basistext&id=81 (last access: 9 October 2025), 2017.

Laslaz, L., Gauchon, C., and Pasquet, O.: Atlas Savoie Mont-Blanc – Au carrefour des Alpes, des territoires attractifs, Autrement, 96 pp., ISBN 2746740281, 2015.

Lazzarotti, O. (Ed.): Habiter. La condition géographique, Belin, Collection Mappemonde, Paris, 288 pp., ISBN 2701143195, 2006.

Parlement français: Loi no. 89-462 du 6 juillet 1989 tendant à améliorer les rapports locatifs, article 2, https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/article_lc/LEGIARTI000047900014 (last access: 9 October 2025).

Marcelpoil, E. and François, H.: Real estate: A complex factor in the attractiveness of French mountain resorts”, Tourism Geographies, 1, 334–349, https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680903053326, 2009.

Marjavaara, R.: Route to Destruction? Second Home Tourism in Small Island Communities, Island Studies Journal, 2–1, 27–46, https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.198, 2007.

Meyer, C., Job, H., and Knoll, L.: Längsschnittanalyse Alpiner Siedlungsgeographie: Das Tegernseer Tal, Bayern, Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Geographischen Gesellschaft, 164, 283–309, https://doi.org/10.1553/moegg164s283, 2022.

Moss, L. A. G.: Beyond Tourism: The Amenity Migrants, in: Coherence and Chaos in Our Uncommon Futures, edited by: Mannermaa, M., Inayatullah, S., and Slaughter, R., Turku School of Economics, Turku, Finland, 121–128, ISBN 9789517384308, 1994.

Müller, D. and Hall, C. M.: Second Homes and Regional Population Distribution: On Administrative Practices and Failures in Sweden, Espace populations sociétés, 21-2, 251–261, https://doi.org/10.3406/espos.2003.2079, 2003.

Nordin, U. and Marjavaara, R.: The local non-locals: Second home owners associational engagement in Sweden, Tourism, 60, 293–305, 2012.

Novljan, Z.: EUSALP perimeter and members, The Alpine Convention [data set], https://www.atlas.alpconv.org/catalogue/csw_to_extra_format/6adc4a64-1722-11ed-9128-0050568ea38e/EUSALP perimeter and members.html (last access: 9 October 2025), 2022.

Office Fédéral du Développement Territorial: Permanent resident population in private households by institutional units and household size, Office fédéral de la statistique [data set], https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/fr/home/services/geostat/geodonnees-statistique-federale/batiments-logements-menages-personnes/population-menages-depuis-2010.assetdetail.177196.html (last access: 9 October 2025), 2010.

Office Fédéral du Développement Territorial: Inventaire des logements et proportion de résidences secondaires, Office Fédéral du Développement Territorial [data set], https://www.are.admin.ch/inventaire-logements#381345584 (last access: 9 October 2025), 2017.

Office Fédéral du Développement Territorial: Permanent resident population in private households by institutional units and household size, Office Fédéral du Développement Territorial [data set], https://www.pxweb.bfs.admin.ch/pxweb/en/px-x-0102020000_401/px-x-0102020000_401/px-x-0102020000_401.px (last access: 9 October 2025), 2019.

Office Fédéral du Développement Territorial: Inventaire des logements et proportion de résidences secondaires, Office Fédéral du Développement Territorial [data set], https://www.are.admin.ch/inventaire-logements#381345584 (last access: 9 October 2025), 2023.

Opensnowmap.org and contributors: piste:type, https://www.opensnowmap.org/iframes/data.html(last access: 9 October 2025), 2022.

Paris, C.: Affluence, Mobility and Second Home Ownerships, Routledge, London, 224 pp., https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203846506, 2010.

Perlik, M.: Alpine gentrification: The mountain village as a metropolitan neighbourhood, Revue de Géographie Alpine, 99, https://doi.org/10.4000/rga.1370, 2011.

Permanent Secretariat of the Alpine Convention: Perimeter of the Alpine Convention, [data set], https://www.atlas.alpconv.org/layers/geonode_data:geonode:Alpine_Convention_Perimeter_2025 (last access: 9 October 2025), 2020.

Perrot, M. and de La Soudière, M.: La résidence secondaire: un nouveau mode d'habiter la campagne?, Ruralia, 2, https://journals.openedition.org/ruralia/34 (last access: 9 October 2025), 1998.

Pitkänen, K., Hannonen, O., Toso, S., Gallent, N., Hamiduddin, I., Halseth, G., Hall, C. M., Müller, D. K., Trevish, A., and Nefedova, T.: Second homes during corona – safe or unsafe haven and for whom? Reflections from researchers around the world, Matkailututkimus, 16-2, 20–39, https://doi.org/10.33351/mt.97559, 2020.

Ragatz, R. L. and Gelb, G. M.: The quiet boom in the vacation home market, California, Management Review, 12, 57–64, 1970.

Rainer, G. and Steiner, C.: Tourism, financialization, and real estate: the transformation of the holiday rental market, Tourism Geographies, 27, 898–916, https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2025.2511737, 2025.

Roca, Z. (Ed.): Second Home Tourism in Europe: Lifestyle Issues and Policy Responses, Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 360 pp., ISBN 9781138279582, 2013.

Robertsson, L. and Marjavaara R.: The seasonal buzz: knowledge transfer in a temporary setting, Tourism Planning & Development, 12, 251–265,

doi10.1080/21568316.2014.947437, 2014.

Sarman, I. and Czarnecki, A.: Swiss second-home owners'intentions of changing housing patterns, Moravian Geographical Reports, 28, 208–2022, https://doi.org/10.2478/mgr-2020-0015, 2020.

Schier, M., Hilti, N., Schad, H., Cornelia T., Dittrich-Wesbuer, A., and Monz, A.: Residential Multi-Locality Studies: The Added Value for Research on Families and Second Homes, Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 106, 439–452, https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12155, 2015.

Sertout, M.: L'avenir des résidences secondaires dans les stations de montagne. Le point de vue des propriétaires: Espaces Tourisme et loisirs, 88–92 pp., https://www.tourisme-espaces.com/doc/9487.l-avenir-residences-secondaires-stations-montagne-point-vue-proprietaires.html?pk_kwd=9487 (last access: 9 October 2025), 2015.

Skoczek, M., Holzhey, M., and Saputelli, C.: Alpine Property Focus 2023, UBS Alpine Property Focus Switzerland, 28 pp., https://www.ubs.com/global/en/wealthmanagement/insights/ chief-investment-office/life-goals/real-estate/ubs-alpine-property-focus/_jcr_content/mainpar/toplevelgrid_1132575/col1/ accordionbox/accordionsplit_18004/table_1904735922_cop_82 0504830.2018830811.file/dGFibGVUZXh0PS9jb250ZW50L2R hbS9hc3NldHMvd20vZ2xvYmFsL2Npby9kb2MvYWxwaW5l LXByb3BlcnR5LWZvY3VzL2VuLTIwMjMucGRm/en-2023.pdf (last access: 9 October 2025), 2023.

Slätmo, E., Ormstrup-Vestergård, L., Lidmo, J., and Turunen E., Urban–rural flows from seasonal tourism and second homes: Planning challenges and strategies in the Nordics, Nordregio Report, 58 pp., https://doi.org/10.6027/R2019:13.1403-2503, 2019.

Société de Développement de Nendaz: Rapport de gestion et d'activités 2022, Nendaz, Suisse, 24 pp., https://static.mycity.travel/manage/uploads/9/66/308423/2/rapport-de-gestion-sd-2022.pdf (last access: 9 October 2025), 2022.

Soszyński, D., Sowińska-Świerkosz, B., Stokowski, P. A., and Tucki, A.: Spatial arrangements of tourist villages: implications for the integration of residents and tourists, Tourism Geographies, 20, 770–790, https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1387808, 2017.

Statistični urad Republike Slovenije: Registrski popis prebivalstva, gospodinjstev in stanovanj v Republiki Sloveniji v letu 2011 [data set], 2011.

Statistični urad Republike Slovenije: Prebivalstvo po starosti, občine, Slovenija, polletno, Sistat [data set], https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStatData/pxweb/en/Data/-/05C4003S.px (last access: 9 October 2025), 2020.

Statistični urad Republike Slovenije: Stanovanja, Slovenija, 1. Januar 2011 – končni podatki, Sistat [data set], https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStatData/pxweb/en/Data/-/0861150S.px/ (last access: 9 October 2025), 2023a.

Statistični urad Republike Slovenije: Stanovanja, Slovenija, 1. Januar 2018 – končni podatki, Sistat [data set], https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStatData/pxweb/en/Data/-/0861150S.px/ (last access: 9 October 2025), 2023b.

Statistični urad Republike Slovenije: Prenočitvene zmogljivosti po občinah, Slovenija, letno, Sistat [data set], https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStatData/pxweb/sl/Data/Data/2164527S.px/ (last access: 9 October 2025), 2024.

Statistik Austria: Bevölkerungsstand, Statistik Austria [data set], https://www.statistik.at/en/statistics/population-and-society/population/population-stock (last access: 9 October 2025), 2010.

Statistik Austria: Nebenwohnsitzfälle am 31.10.2013 nach Geschlecht und Gemeinden, Statistik Austria [data set], https://www.statistik.at/statistiken/bevoelkerung-und-soziales/bevoelkerung/bevoelkerungsstand/nebenwohnsitze (last access: 9 October 2025), 2013.

Statistik Austria: Bevölkerungsstand, Statistik Austria [data set], https://www.statistik.at/en/statistics/population-and-society/population/population-stock (last access: 9 October 2025), 2020.