the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

“His dead body is in the water right now” – death, survival, and hypermobility along the Balkan Route

Philipp Themann

This article examines the deaths of migrants in the expansive natural landscapes of the Balkans, which are framed here as “weaponized landscapes” and, consequently, as integral components of border security. During the forced traversal of these landscapes, individuals seeking protection are exposed to great suffering, (re)traumatization, and even death. The discussion also considers the preconditions for such fatalities, primarily the precarious conditions in (in)formal camps across the Balkans and the illegal pushbacks carried out by border officials. Drawing upon the extant academic discourse surrounding camps and mobility studies, this article argues that these preconditions render migrants in the region hypermobilized. In a state of survival, these migrants often opt for increasingly risky routes, further driving their clandestine and illegalized escape across the borders of the European Union.

- Article

(417 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

The Balkan Route is a crucial corridor for migrants making their way to western and northern Europe. After the “long summer of migration” in 2015 (Hess et al., 2017), the route has been politically closed by the so-called EU–Turkey declaration and heightened migration controls at Europe's external borders (Speer, 2017). Additionally, the transit countries of the western Balkans (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia, Kosovo, North Macedonia, and Albania), which are in accession negotiations with the EU, have been working closely with FRONTEX, the EU's border control apparatus, to control and restrict the movement of refugees within their territories. However, increased migration controls have not signaled an end to migratory movements. On the contrary, migration along the route has become more dynamic, with an increasing number of alternative pathways emerging between the region's central hubs (IOM, 2023).

Most migrants traveling along the Balkan Route are fleeing countries such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iraq. Their clandestine journeys take them along winding paths in an attempt to cross Europe's external borders. However, intensified migration controls, tighter security, and border obstructions prevent many from doing so. If discovered by Hungarian, Croatian, or Bulgarian border guards, they are forcibly “pushed back” across the border without being granted access to asylum procedures. As a result, tens of thousands of refugees remain stranded in the vast border areas along the Balkan Route – simultaneously stuck in different transit countries and “on the move” between different transit points. Some find temporary refuge in official camps, informal shelters, or border towns outside Europe's external borders, yet they endure highly precarious living conditions, including discrimination, criminalization by local authorities, and exploitation by the migration industry.1 Nevertheless, they persist, moving within and between migration centers in these regions (Themann and Etzold, 2023:538).

As part of my research in the region, I have spoken to individuals who have been stuck in these border areas for several months, sometimes even years, and have made countless attempts to cross the Croatian, Hungarian, and Bulgarian EU external borders. Their stories resonate with Jason De León's (2015) description of “weaponized landscapes” across the Sonoran Desert along the US–Mexico border. In his exhaustive ethnographic study, De León illustrates how migrants are compelled to traverse perilous routes through the Sonoran Desert in Arizona, effectively transforming the natural environment itself into a lethal instrument. Similarly, due to the persistence of illegal pushbacks, people seeking protection on the Balkan Route are forced to traverse the vast wilderness of the region again and again in their efforts to reach northern and western Europe undetected. Their experiences demonstrate how the natural landscapes along the Balkan Route serve not only as physical barriers but also as weaponized landscapes – violent, strategically utilized spaces actively employed by state actors as instruments of violence, surveillance, and deterrence. These practices of border violence transform the region into a hybrid space where the environment, technological surveillance, and state violence are closely intertwined. By deliberately using the natural environment as a weapon, those seeking protection are driven into hostile spaces where they are exposed to great suffering, traumatization, and even death.

But why are people seeking protection forced to remain in the remote wilderness of the Balkans in the first place and under what circumstances do they die? To address this question, I focus on the preconditions for migrant deaths along the Balkan Route, an aspect that has yet to be sufficiently analyzed in (geographical) forced-migration research. Therefore, in this article, I examine the factors that expose migrants to life-threatening situations as they attempt to reach western and northern Europe, leading to deaths in the remote wilderness of the Balkans. As will be demonstrated, these preconditions are characterized by the precarious living conditions in (in)formal camps across the region and the widespread practice of illegal pushbacks by border officials. Given the paucity of documentation concerning the living conditions of migrants along the Balkan Route – particularly in comparison to those on the Greek islands or in the so-called “jungles” of northern France (Jordan and Moser, 2020:3; Minca et al., 2018:5) – it is my intention to bring greater visibility to the conditions of their journeys through the region. While much of the existing academic literature on migrant fatalities in natural environments has focused on the Mediterranean region (e.g., De Genova, 2017; Gebhardt, 2020; Schindel, 2022) or the topography of the Greek islands (e.g., Mountz, 2011), this study draws attention to the expansive wilderness of the Balkan Route.

To better understand how the precarious living conditions of refugees in (informal) camps arise and what effects they have, Sect. 2 engages with the academic discourse on camps. Additionally, it examines approaches from the field of mobility studies to explore the effects of state migration controls and the significance of immobility, forced mobility, and hypermobility. Building on this conceptual framework, the section discusses the role of natural landscapes, emphasizing the extent to which these weaponized landscapes are used to slow down; impede; or, in extreme cases, prevent the mobility of migrants – ultimately leading to migrant deaths. Section 3 then briefly outlines the methodology of data collection and the associated ethical challenges.

Section 4 presents the study's primary findings. First, it elaborates on the death of refugees along the Balkan Route, as well as the potential dangers migrants face in these vast weaponized landscapes. It then focuses on the preconditions for these deaths, analyzing the precarious life in (informal) camps and the role of pushbacks as a key mechanism of migration control. The section concludes by arguing that cross-state migration control has led to the hypermobilization of migrants in the region – that is, migrants are compelled to remain in constant motion and are thereby forced to take increasingly risky partial routes in remote natural landscapes.

The Conclusions section provides a brief synopsis of the most salient findings and argues that the preconditions for migrant deaths are shaped by precarious conditions in (informal) camps, illegal pushbacks, and the resulting hypermobilization of migrants. Hypermobilization is conceptualized as a hybrid state of involuntary immobilization in camps and forced mobilization between transit points and alternative routes. This dynamic has forced many migrants to traverse perilous, remote landscapes, with their deaths being framed as an inherent consequence of policies designed to deter their further movement.

The increased risk of death for (marginalized) population groups or other living beings has been widely discussed in recent academic debates in the fields of migration, border regime, and violence studies, as well as in the disciplines of political ecology and public health (Davies et al., 2017; Estévez, 2022; Gao et al., 2023; Grenfell et al., 2023). Disparities in survival chances resulting from state violence, neglect, and exclusion have been examined in relation to the growing prevalence of racism and femicide (Wright, 2011). Some studies have specifically focused on different forms of state regulations based on life-enhancing biopolitics. Additionally, the implementation and effects of so-called necropolitics – which describes how certain population groups are systematically exposed to death – have become central topics in contemporary academic discourse (introduction to the special issue).

Some scholars have drawn on Foucault's (1999) concept of biopower to describe how life is managed and disciplined to define the health of a particular population. According to Foucault (1999:297), “killing” extends beyond physical death to include more indirect forms of violence, such as exposure to death, increased risk of death for certain groups, political death, and even expulsion or deportation. A Foucauldian lens has been widely adopted in analyses of Europe's migration regimes. For instance, individuals who reach Europe's borders but do not meet its migration criteria are often deported to extraterritorial zones, where they are reduced to their “naked biological existence” and dehumanized (Gebhardt 2020:123). Building on Foucault's foundation, Mbembe (2003) developed the concept of biopolitics further, arguing that Foucault's focus on the internal mechanisms of state power does not sufficiently account for externalized violence and colonial histories. Mbembe thus introduced a necropolitical understanding of sovereignty in order to analyze direct control over life and death in postcolonial contexts. His work accentuates the role of violence, neglect, and exclusion in the exercise of power, with death serving as a central category in his analysis.

Building on these theoretical foundations, I now turn to the academic discourse on camps and mobility studies. The study of camps provides a conceptual framework as it addresses the immobilization of migrants as a central mechanism of state migration control (see Turner, 2015; Oesch, 2017; Martin et al., 2019). These studies can help us understand how the immobilization and exclusion of refugees take place and what effects the precarious conditions in camps can have. Expanding on this, I introduce camps as a key instrument of migration control, structured along temporal, spatial, and legal dimensions. These structures make camps a fundamental precondition of migrants' deaths in the natural landscapes of the Balkans.

In this context, mobility studies facilitate our examination of mobility and immobility within an analytical framework that does not perceive them as diametrically opposed but as interconnected and dynamic processes (Schewel, 2019). As will be argued, migration control in the region engenders a hybrid state of involuntary immobilization in camps and forced mobilization between various transit points and alternative routes. It is this oscillation between involuntary immobilization and forced mobilization that I refer to as a form of hypermobilization – a condition that contributes significantly to the displacement of migrants into remote natural landscapes, where they endure immense suffering and, in some cases, death.

At the end of this section, I discuss the extensive natural landscapes that are difficult to traverse and introduce the concept of weaponized landscapes. This term frames natural landscapes as elements of border protection, helping to avoid depoliticizing, naturalizing, or normalizing migrant death in these environments as merely regrettable and self-inflicted accidents (Schindel, 2022:431). As I argue later, the deaths of those seeking protection in these landscapes are a calculated consequence of migration controls, largely driven by hypermobilization.

2.1 Beyond shelter: camps as instruments of migration control and social dissolution

A central aspect of refugees' immobilization is their extraterritorial confinement in camps, a topic that has been extensively explored from the perspective of camp studies (e.g., Brun, 2015; Brun and Fábos, 2015; Turner, 2015; Oesch, 2017). The placement of refugees in camps serves as a key tool in international migration management aimed at regulating and reducing the number of arriving refugees. Camps vary significantly in terms of their size, legal frameworks, and degrees of (in)formality, as well as in terms of the living conditions of their inhabitants (Minca et al., 2018; Themann and Etzold, 2023:539–540). Spatial biopolitical techniques are deployed to temporarily “detain” camp residents, reducing them to their “naked' biological bodies” while granting them only minimal access to basic necessities such as food, water, and sanitation – effectively holding them in a liminal state between life and death (Aradau and Tazzioli, 2019; Breuckmann, 2025; Martin et al., 2019:754).

The academic discourse on camps also examines their defining characteristics and the ways their spatial, legal, and temporal conditions shape the lives and perceptions of their inhabitants. A primary point of emphasis is that camps are always exceptional in terms of their legal arrangements, operating under frameworks distinct from those of the surrounding areas (Martin et al., 2019). From a temporal perspective, camps are conventionally framed as temporary shelters, reflecting the widespread assumption that forced migration is a transient phenomenon. Refugees are expected to reside in these camps for a limited duration, though, in practice, the duration of camp operations – and the actual length of stay – often remains uncertain, even to the camp's administrators (Turner, 2015:142). Consequently, camps frequently become quasi-permanent spaces of exception, where refugees encounter protracted immobilization and marginalization within unequal power dynamics (Kreichauf, 2018).

In this vein, some scholars have drawn on Giorgio Agamben's (1998) concept of “bare life” and the ancient legal category of “homo sacer” to describe how “abnormalized groups” in the Nazi concentration camps were left unprotected at the mercy of a sovereign power. Building on this, various authors have analyzed refugee camps and border areas as torturous environments within a necropolitical framework (Manek, 2024), where those seeking protection are reduced to their bare life or mere biological existence (e.g., Buckel and Wissel, 2010; Dines et al., 2015; Schindel, 2016).

Although the camp can be understood as a denormalized place where refugees are spatially and legally excluded, it does not solely produce depoliticized bare life in the Agambenian sense (Turner, 2015:139). Patricia Owens (2009) highlights the need for critical scrutiny of Agamben's conceptualization as the political participation and agency of migrants, as well as their diverse forms of resistance, remain inadequately addressed. In this vein, some studies have shown that camps can also function as meeting places where the autonomy of migration materializes, negotiation processes are fought out, resistance emerges, and preparations for future mobility take place (Martin et al., 2019:745; Themann and Etzold, 2023:542–543).

In this article, I examine the role of camps in the context of migration control through a variety of temporal, spatial, and legal dimensions. The central argument is that these camps operate as sites of social dissolution, where refugees encounter an elevated risk of mortality, political persecution, and even expulsion or deportation (Foucault, 1999:297). Additionally, the discussion will explore the precarious nature of life within these settings and how they function as zones of state regulation over migration. As I will demonstrate, these aspects serve as a central precondition for the death of refugees in the vast natural landscapes across the Balkans.

2.2 Governing movement: the power politics of mobility and immobility

Past academic debates on migration and (im)mobility were often shaped by or reinforced normative values. Humans are frequently classified as fundamentally sedentary beings, a perspective that naturalizes immobility or sedentarism as the default state while framing migration or mobility as a kind of “state of exception” (Verne and Doevenspeck, 2012:65; Schewel, 2019:331). In response to this, mobility studies and the “new mobility paradigm” have taken a more differentiated approach to conceptualizing mobility and migration (Etzold, 2019:16; Sheller and Urry, 2006)

The new mobility paradigm emphasizes the transformative power of mobility systems. The increasing interconnectedness and circulation of people, services, goods, norms, and transactions lead to extensive restructurings of social and political life across various scales (Etzold, 2019:18ff.). These restructurings tend to be accompanied by a variety of reactions, (counter)measures, and (infra)structural practices aimed at containment. Within this paradigm, migration and mobility management are framed as hegemonic political projects deeply intertwined with different and oftentimes racialized discourses (Kreichauf, 2018:14f.).

Based on these discourses, attempts are often made to restrict or control migration and mobility. For example, individuals without citizenship privileges are immobilized at an early stage through the externalization of the European migration and border regime, frequently confined to extraterritorial spaces. These inequalities in terms of mobility are further regulated through access to the global transport infrastructure. Spijkerboer (2018:469) notes the following:

The global mobility infrastructure is populated by a disproportionally white, disproportionately wealthy, and disproportionately male population. … The zone surrounding the global mobility infrastructure … is populated disproportionately by a non-white, poor, and female population. The excluded do not have access to quick and safe transport, and ironically, their cross-border travel will usually be more expensive.

In this sense, (im)mobility is inherently an expression of unequal power relations, a prominent theme in studies on migration autonomy or border regimes (Hess and Kasparek, 2010; Hess et al., 2017; Heimeshoff et al., 2014).

However, it is imperative to dispel the notion that mobility is exclusively associated with extensive opportunities for action and to avoid framing it as a resource that is withheld from marginalized individuals by state regulations. In her article on mobility as a mode of governance, Martina Tazzioli (2019) asserts that mobility and immobility, in and of themselves, do not necessarily represent expressions of agency or marginalization. Instead, she argues that a heightened focus on the self-determination of (im)mobility can facilitate a more nuanced understanding of it as both an object of control and a technology of governance. In her study, Tazzioli (2019) illustrates how migrants in France and along the Italian–French and Italian–Swiss border regions are kept on the move, separated from one another, and dispersed through state-led mobilization. This forced mobilization, she argues, is designed to exhaust migrants, disrupt their social ties, and channel their movements along convoluted sub-routes. As I demonstrate below, this perspective helps us understand how migrants on the Balkan Route are hypermobilized between (informal) camps, transit sites, and alternative routes, ultimately leading to deaths in the vast wilderness of the Balkans.

2.3 Landscapes as tools of migration control: the crossing of natural landscapes

The concept of weaponized landscape refers to the strategic use of natural spaces in the context of conflicts and warfare. While often used in a militaristic sense to denote the deliberate manipulation of terrain (such as the mining of transit corridors), the term can also be used as a means to control or impede migration. Mountain ranges, deserts, dense forests, and other terrains can function as natural barriers that make border crossings more difficult (Schindel, 2022:433ff.).

Migrants frequently face extreme environmental conditions that can lead to traumatization; severe injuries; and, in extreme cases, death. While these landscapes can be effective in impeding or even preventing migration, they also raise numerous ethical and humanitarian concerns, especially when migrants are forced by migration controls and transnational state violence to cross ever more extreme or even life-threatening natural spaces for their clandestine escapes.

Some scholars have devoted their work to specifically analyzing how natural landscapes serve as tools for controlling or impeding migration. De Léon (2015), for instance, employs actor-network theory to illustrate how extreme environmental conditions of the Sonoran Desert in the US operate as part of a “hybrid collective” of human and non-human forces that deter migrants from entering the country. Working in the same geographical context, Johannes (2017) similarly posits that the desert has become inseparable from the meanings of death and, altogether, resembles a “landscape of death”.

Mountz (2011) shifts the focus to islands, examining their topographical significance in restricting access to asylum. She identifies islands as sites of territorial conflict where migrants are trapped in legal ambiguity, shaped by biopolitical and sovereign forces that transform them into an “archipelago of detention.”

There has also been an emerging body of literature investigating the growing number of migrant deaths in the Mediterranean (e.g., De Genova, 2017; Gebhardt, 2020; Schindel, 2022). De Genova (2017:3) places particular emphasis on the increasing militarization of European border areas, describing the Mediterranean as a mass grave. Schindel (2022) refers specifically to slow forms of violence and how geographical and topographical features of the Greek islands are used as border control strategies to make crossings more dangerous. In a related argument, Gebhardt (2020) describes European border policy as one that deliberately allows people to drown as a means of asserting sovereignty.

Natural landscapes also serve as elements of border enforcement along the Balkan Route, though relatively few studies have examined this in depth. An exception is Hameršak and Pleše (2021), who explicitly analyze conditions of death and survival along the Balkan Route in terms of weaponized landscapes. They describe some of the forests between Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, and Croatia as places of surveillance, imprisonment, pushback, and suffering, drawing primarily on publicly available data repositories from regional activist networks.

In recent years, European Member States have implemented numerous measures to control and restrict migration along the Balkan Route. Beyond direct state interventions, natural barriers such as rivers, mountain passes, and forests have increasingly been leveraged to impede the movement of migrants, making onward travel more difficult and heightening the risk of accidents and injuries. Mountain ranges along the Balkan Route, such as the Dinaric Alps and the Balkan Mountains, present particularly formidable obstacles. Rivers like the Sava, Danube, and Drina, as well as many smaller border rivers, act as natural barriers that are often challenging to cross. Meanwhile, the dense forests along the route serve a dual role: while they provide temporary refuge to avoid state detection, they also pose significant dangers. Migrants navigating these forests risk disorientation, exposure to extreme environmental conditions, and life-threatening situations, especially if they lack adequate equipment or knowledge of the terrain (Hameršak and Pleše, 2021).

This article draws on several intermittent periods of fieldwork between 2020 and 2025. During this time, I conducted a total of 25 semi-structured interviews with migrants along the European external borders in Bosnia, Serbia, Croatia, and Bulgaria, as well as 10 semi-structured interviews with NGO employees and local residents.2 The interviews took place in (in)formal camps or their immediate vicinity. They were conducted in English, recorded with an audio device, and then thematically coded and analyzed with MAXQDA. For this article, I selected interviews in which participants discussed their experiences crossing forests and mountain areas. Other topics covered in the interviews included state violence, different mobility practices, and the importance of translocal networks. Most of the interview excerpts used here come from male migrants between the ages of 20 and 30, primarily from Pakistan, Kashmir, Afghanistan, and Iraq. Additionally, I include an interview with a young mother from Afghanistan who fled with her husband and 2-year-old son.

During fieldwork, I encountered several significant ethical and methodological challenges that necessitated adjustments to the research process, largely due to the fact that the interviews were conducted with vulnerable groups of people. Bank et al. (2017) conceptualize forced migration as a fragmented process in which refugees move from one order of violence to another, often experiencing extreme trauma. This was evident during my research stays as the health and emotional states of my interviewees were often deeply worrying.

Given these circumstances, my initial plan was to work as a volunteer, conducting open, participatory observations or concentrating my analysis on various NGOs as an alternative research subject. However, early on, it became evident that many individuals seeking protection were eager to speak about their experiences. In some cases, spontaneous encounters and extended time spent together culminated in genuine interviews, which were conducted employing trauma-informed interview techniques (e.g., Shankley et al., 2023). For some interviewees, the publication of their testimonies was considered to be of paramount importance.

In accordance with the stipulated research ethics, interviewees determined the extent of the insights they wished to divulge, ensuring that the process remained neither invasive nor voyeuristic. This commitment to self-determination also aligns with the principle of the right to opacity, as articulated by Khosravi (2018:294). Respecting this right ensures that individuals seeking protection are not compelled to relinquish their autonomy or confidentiality. The analysis of the research findings is based on a selective approach, focusing only on information about places and practices already known in the region. This is intended to avoid drawing attention to locations or practices where refugees prefer to remain undetected due to the risk of state repression. Consequently, not all statements made by interviewees can be equally weighed or compared.

Furthermore, the duration of stay in both formal and informal camps was subject to the discretion of local security personnel or police. In the event of any contact with these actors, it was necessary to renegotiate whether I, as a researcher, was allowed to remain in the camp or had to leave. Such exclusions appeared to be arbitrary and individualized; for example, I was sometimes granted access to informal camps on certain days but was denied entry on others or after a shift change.

I also aimed to contribute to improving conditions on the ground through my research. To this end, I engaged with various NGOs in the region as this provided opportunities for mutual exchange and gave me a chance to support their humanitarian work, particularly in planning efforts (e.g., by exchanging information about the living conditions of migrants at other transit points in the region). Furthermore, my findings had direct applications in the context of civil-society discourse, for instance, in the domain of educational initiatives or artistic installations. These are developed in collaboration with NGOs that are also active in the region. It should be noted that this use will only take place after consent has been given by the respondents, with whom ongoing contact is maintained in certain instances even after the conclusion of the research stay.

In this section, I begin by discussing the deaths of migrants along the Balkan Route and the circumstances under which they occur. I then focus on deaths within natural landscapes, presenting these as weaponized landscapes. The following section addresses the preconditions of migrants' deaths, which are mainly characterized by forced immobilization in (in)formal camps in the Balkans and illegal pushbacks by EU border guards. Finally, I examine the consequences of these migration control strategies, arguing that migrants are hypermobilized within the region. This condition compels them to take increasingly risky sub-routes to reach western and northern Europe, exposing them to heightened risks of death.

4.1 Death and survival in weaponized landscapes

Documenting fatalities along the Balkan Route poses significant challenges due to the dynamic nature of the border region, which is in constant flux. The border corridor, stretching from Bulgaria and North Macedonia in the south to the Schengen states of Croatia and Hungary in the north, is continuously evolving, making it difficult to systematically record deaths. The clandestine nature of illegal border crossings and migration further hinders comprehensive reporting. As such, documentation of deaths primarily relies on witness testimonies, followed by subsequent reporting by family members or acquaintances. Collaboration with NGOs and government agencies is essential for official and central recording, including the identification, recovery, and burial of bodies, as well as the processing of personal details. Reports from NGOs and journalists in the region have noted the existence of numerous graves in municipal cemeteries and other sites where bodies are interred in unidentified graves (see, for example, Klikactive, 2023; Lighthouse Reports, 2023).

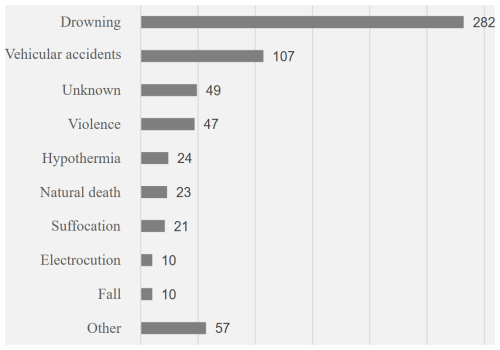

The 4D database, which has registered at least 632 deceased migrants along the Balkan Route since 2015 (4D, 2025a), provides an overview of these recorded deaths.3 Nearly half of the reported deaths are attributed to external environmental factors such as drowning in rivers and hypothermia (see Fig. 1). However, the database also records fatalities resulting from traffic accidents, violence, and natural causes, as well as cases where the cause of death is unknown. It should be acknowledged that the registered deaths in the database may not fully reflect actual trends as there is a possibility that a significant number of cases remain unreported (4D, 2025a, Sect. 1).

During my research, I primarily encountered fatalities related to external environmental conditions that occurred during illegalized crossing of vast natural landscapes. I will discuss these in greater detail in the following sections.

The physical exertion involved in illegalized border crossings was a recurring theme in the interviews I conducted. Due to the enormous physical efforts involved in these crossings, the journey must be made with as little luggage and equipment as possible. As one interviewee told me, “We sleep in the forests. […] Just down on a plastic tarp.” (Migrant from Pakistan) Many refugees organize crossing these natural landscapes on their own, using the smartphones they carry with them to navigate the border area: “most people go by tracking [the path] with their cell phone. If a person has money, he takes an agent.” (Migrant from Pakistan)

These peripheral natural landscapes are marked by extreme environmental conditions, rugged topography, and extensive wilderness, contributing to their characterization as weaponized landscapes. Interviewees frequently emphasized the perilousness of these extreme environmental conditions, including encounters with wild animals and exposure to extreme cold. Because of the natural hazards, crossing these weaponized landscapes is usually done in small communities:

I am not able to go alone in the forests. You know, it's a lot of wilderness. There are forest animals. And so, we make a group and go. […] Snow is falling outside there. Much of snow. Last week, I came back from the forests in Croatia. When I saw that heavy snow, I came back. I hope to find a better solution. (Migrant from Pakistan)

In traversing these landscapes, migrants must also confront numerous natural barriers, such as mountain ranges and rivers. For those in border areas along the Balkan Route, there are no alternatives but to forcibly cross these barriers. An NGO worker from Serbia mentioned that, since the “long summer of migration” in 2015, official or safe transit routes to western or northern Europe have ceased to exist:

Some years ago, many of these borders were imaginary. They were political borders. Now, they're physical fences that you have to cross. Now, they're natural barriers that you have to cross. The Balkans have already so many natural barriers to accessing the European Union. The European Union really is made like a fortress, per se. And then it's like constantly this discourse about `Let's make it safe. Let's prevent people from human trafficking.' But there is no alternative to it. There are no safe routes. There are no humanitarian corridors. There are no schemes. (Interview NGO 1, Serbia)

The perilousness of these journeys is starkly illustrated in an account shared with me about a group of individuals attempting to cross a river into Croatia:

Five friends of mine went on game last week.4 When they were in Croatia, there is one river. My friends cross that river, and unfortunately, one guy drown in the water. He was a friend of mine. It happened 2 days ago. The other guys called the police. When police come, my friends told them that one guy drown in the river, and they ask for help. The police make jokes about that and start to laugh. They don't care about that. They pushback them. I have a friend in Croatia; she is a journalist. I explain her the situation and ask her to raise her voice. She asks me for the name of my friend. I told her and said that he was 23 years old, from Pakistan. That he died in a Croatian river 2 days ago. So, that's the story of my friend. His dead body is in the water right now. (Migrant from Afghanistan)

These landscapes are also crossed by particularly vulnerable migrants. For instance, one interviewee described the dangers she faced while traveling with her husband and 2-year-old son, clearly demonstrating how the vast wilderness can traumatize parents and children and even cause the death of an unborn child:

The forest from Montenegro to Bosnia was the hardest way for us; we walked days without any stop, and our food and water was finished. We were so lucky that we found a river somewhere to refill our bottles. The wilderness and the sound of animals in the night. […] We saw the places where the predators eat their prey. This makes we very afraid. […] We try to get out of this quickly and started very hard walking. Unfortunately, I was pregnant, and I think the hard walking without water and food was the reason why I lost my baby in the forests in Bosnia. […] It was very sadly for me. […] But I am happy that I have my son here. But he cannot speak yet, and he is not trying it anymore because he is still afraid. He passed very bad days in the forests. All the time, he was crying […] because he felt so cold and afraid at these forests. He asked me, `Mommy, please go back home, please go back home,' all the time. (Migrant from Afghanistan)

This poignant account from a mother from Afghanistan vividly illustrates the multiple layers of vulnerability experienced by migrants along the Balkan Route. Exhaustion from days-long forced marches; lack of basic resources such as food and water; and constant exposure to threats from wild animals, extreme cold, and disorientation produce not only physical depletion but also profound psychological trauma. The loss of her unborn child stands as a stark example of the consequences emerging from the intersection of state violence, the abdication of humanitarian responsibility, and the deployment of naturalized border technologies.

In this context, the landscape along the Balkan Route is no longer a passive space of transit – it is actively instrumentalized as part of a violent border regime. State security actors play a central role in this process, not only through the exertion of direct violence (see Sect. 4.3) but also by deliberately obstructing civil-society rescue efforts. As one activist recalled,

One evening, we received different videos of minors lying in the snow in terrible conditions. We decided to call 112. Instead of sending an ambulance, however, they just told the border police. You can call 112 as many times as you want. You can tell them how bad it is, that people are dying, and they don't care. We knew this, and we knew we had to try to find these people. We couldn't go any further because we came to a flooded road. It's something you could easily cross with a Border Patrol Defender, but with our car, there was no way to do that. Two minutes later, the border police arrived. They receive millions of euros from the European Union, and they have drones and Jeeps. Instead of using them to help minors, they use them to stop us. We tried to explain the situation. But the Bulgarian border police didn't care. They got out of the car and started yelling at us. They wanted us to sit down. We were standing in a line on the street while they yelled some things in Bulgarian that I didn't understand. Then, we walked for 3 hours to the next village. It was 10 kilometers, and the border police were behind us the whole time. During that time, the minors froze to death in the forest. The following night, we tried to reach the first minor. By that time, more than 24 hours had passed. The boy was literally frozen to death. I checked to see if he was still alive and tried to lift his arm. He was completely frozen. The criminal police came and actually wanted us to carry the body to the car, but we refused. In hindsight, we regret not doing it because then they did it themselves. They picked up the body and threw it in the car. It was awful to watch, to be honest. Another team was trying to reach the other locations as well. They found the second and third bodies.

The death of these underage refugees marks the tragic outcome of a border regime that prioritizes deterrence over protection. Their deaths stand as a stark example of the failure of European migration policy5. As these testimonies demonstrate, migrants are left to fend for themselves in this vast wilderness of the Balkans, and, in the process, they are exposed to immense suffering, traumatization, and even death. State violence at the EU's external borders is compounded by the elemental forces of nature to which those seeking protection are subjected. These forces include the characteristics of the terrain – such as remote forests and mountainous regions – alongside weather conditions like extreme cold and snowfall, the presence of wild animals, and natural obstacles such as rivers. In the words of Hameršak and Pleše (2021), these natural landscapes can be conceptualized as weaponized landscapes, denoting their utilization as instruments of restricting and impeding the movement of individuals seeking refuge.

The accounts of the person who drowned in the river and the minors who froze to death also underscore how these landscapes become specifically weaponized through the convergence of harsh environmental conditions and indifferent or overtly hostile state actors. Rather than serving merely as natural obstacles along migratory routes, rivers, forests, and mountainous terrains are actively co-opted into a broader apparatus of border enforcement. In this process, the natural features of the terrain are not neutral; they are transformed into instruments of exclusion through neglect, inaction, and the strategic absence of humanitarian support. The failure – or refusal – of authorities to provide timely assistance effectively turns the landscape itself into an extension of the border regime, amplifying its capacity to harm. These so-called “natural” dangers become politically charged spaces where state abandonment and natural exposure intersect, often with fatal consequences for those in transit.

4.2 “We need help” – (in)formal camps as death worlds

In the following, I address the preconditions that lead migrants traversing the Balkan Route to encounter perilous circumstances during border crossings. A salient component of these preconditions pertains to the precarious living conditions prevalent within regional camps. Accommodation in state-run camps is a central element of migration control on the Balkan Route, aimed at reducing and regulating the number of arriving refugees. This section focuses on the accommodation conditions at Camp Lipa in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2021.

Camp Lipa was opened in April 2020 in the remote mountainous region of the Una-Sana Canton, near the Croatian EU external border in northwestern Bosnia. After the International Organization for Migration (IOM) withdrew as the camp's operator on 23 December 2020, a fire destroyed most of the camp's infrastructure a few days later. Subsequently, the administration of the camp was taken over by the cantonal police in Una-Sana (Themann and Etzold, 2023:531).

At the time of data collection, the camp lacked official access to electricity, running water, and sanitary facilities. The devastating fire at the camp also meant that residents had to set up their sleeping quarters on the bare floor of a remaining large tent. However, since there was not enough space to “accommodate” all residents, some were forced to move into self-built accommodations in the vicinity of the camp. In these self-built temporary shelters, which primarily consisted of collected wooden planks with plastic tarpaulins stretched over them, residents were exposed to harsh winter temperatures without any additional protection (Themann and Etzold, 2023:542). Due to the low temperatures and snowfall, some residents decided to use the non-functional toilet containers for shelter and literally slept between urinals. These catastrophic conditions were reflected in the interviewees' descriptions:

They [security personnel in camp or journalists] are just looking at us like we are animals. I am a human being, and all the migrants sleep inside the toilets, inside the washrooms; there is no proper place. (Migrant from Afghanistan)

The situation is very bad here. The weather is freezing here; we are homeless, we are helpless. The Bosnian government totally failed to provide us with shelter, provide us with food or clothes. (Migrant from Pakistan)

Here is no shower, no electricity. […] We have to go to the mountain area for washing us [little stream near the camp]. That is the situation we are suffering now. Who is gonna listen to us? (Migrant from Afghanistan)

In addition to these dismal accommodations, food was limited to one ration per day. These precarious living conditions were exacerbated by the lack of government support and the winter weather. Some people did not have the strength to walk long distances in sub-zero temperatures and thus had to change their place of residence or flee from Croatian border guards when trying to cross the border (see the following section):

Only half bread and one canned meat and half liter water for one day. […] Now, we do not have energy to run. Because of the hunger. The hunger destroyed everything. (Migrant from Afghanistan)

They are giving us nothing. In 24 hours, they just giving us just half bread and one bottle of water. (Migrant from Pakistan)

So, what should we do? […] We are dying here. (Migrant from Afghanistan)

With Camp Lipa and the surrounding area under police control, coupled with strict access restrictions for volunteers and NGOs, no informal relief structures could be established on the ground. In the absence of adequate infrastructure and a chronic shortage of food, this deliberate exclusion of non-governmental aid structures – enforced by local police – has resulted in considerable suffering among the camp's inhabitants. In the case of the burned-down Camp Lipa, this structural state violence was clearly demonstrated by the fact that refugees were not provided with adequate shelter or food by the government for weeks, while NGOs waiting with mobile kitchens and large tents in the nearby town of Bihać were denied access to the camp and surrounding area.

Although camps are generally designed as temporary spaces where refugees stay only briefly, the case of Camp Lipa illustrates how such places can become quasi-permanent spaces of exception. Originally intended as a temporary summer facility and unequipped for the harsh winter conditions, the camp nonetheless remained operational by cantonal authorities throughout the colder months. Even after a devastating fire completely destroyed the existing infrastructure, refugees continued to be “accommodated” there. For the camp's residents, this resulted in a quasi-permanent condition marked by extreme precarity, aligning with broader debates on the enduring nature of refugee camps (Kreichauf, 2018; Turner, 2015:142). This context also made apparent how the active withdrawal of state obligations through violent inaction leads to substantial misery and suffering. Such inaction is often coupled with proactive regulations, exclusions, and prohibitions that also target living conditions in informal camps and throughout the entire transit areas where migrants stay.

Beyond state-run camps, which frequently have limited capacity, migrants also seek accommodation in informal camps. These can include empty houses, old factory buildings (so-called “squats”), and self-constructed camps in the remote wooded surroundings of transit areas (referred to as “jungle camps”).6 Because these informal camps are typically located near borders, they tend to serve as hubs for refugees on their way to the EU's external border or returning after illegal repatriation. These camps are thus crucial for both onward movement to the EU and survival during forced displacement. However, living conditions in these camps are extremely precarious due to a lack of state support and poor infrastructure. Access to running water, electricity, medical care, and sanitation is rare. Food and supplies – such as sleeping bags, clothing, and backpacks – are usually provided by volunteers. Due to police persecution, though, deliveries primarily occur at night and at hidden drop-off points and have become increasingly criminalized. These precarious conditions force migrants to remain mobile as staying in one place for long is often untenable (Themann and Etzold, 2023:538–539). One interviewee from Iraq, living in an informal camp near the Croatian external border, described these conditions:

Our situation here is very bad; we don't have food, we don't have water for drinking, we don't have any clothes for sleeping. The situation is very bad. […] We need help. We cannot stay here. You know, the weather is very cold. […] It is our big problem. (Migrant from Iraq)

Residents of informal camps also face the constant risk of unannounced and spontaneous evictions. Camp residents may be subjected to physical abuse:

They [the Bosnian police] ride on us and catch us, sometimes they beat us and then […] they push us back to Camp Lipa. (Migrant from Afghanistan)

In addition to physical abuse, spontaneous evictions inflict significant psychological stress since those seeking protection are transported to distant and remote camps after being evicted, as one NGO worker emphasized:

At the same time, they can be evicted from the [informal] camps at any time. And this means that they are taken to another part of the country. [Then,] they have to spend money and time again to get back […] to the borders. […] That causes incredible stress. (Interview NGO 1, Bosnia)

The health conditions of those living in these informal camps are also dire, exacerbated by repeated attempts to cross the EU's external border. Common injuries include lacerations, animal or insect bites, swelling, sprains, and fractures. Many of these injuries result from violent pushbacks by border officials – either through direct physical force or from fleeing across hazardous terrain (see Sect. 4.3). Months of malnutrition, frigid winter temperatures, and poor hygiene further compound these health risks. Parasitic skin diseases, especially scabies, and gastrointestinal and respiratory illnesses are prevalent. Some diseases stem from burning garbage for warmth due to a lack of firewood, while others arise from cross-contamination between local streams and drainage ditches. One interviewee, during an informal conversation, noted that newly arrived residents often suffer from gastrointestinal illnesses for 2 to 3 weeks until their immune systems have adjusted to the microbiological contamination of the drinking water.

Access to official medical treatment is severely restricted as it requires a valid identity card from a formal camp. As a result, irregular treatment is provided by a small number of volunteers, though this is largely limited to basic pain relief:

We need medicine. […] We not able to manage it. Sometimes, someone comes [volunteers] and gives us ibuprofen tablets. (Migrant from Pakistan)

We don't have medicine or another option. We can't go to doctor. If we go to hospital, they ask for documents. (Migrant from Afghanistan)

Some refugees also report that they are unable to move freely in public spaces or along transportation routes due to arbitrary controls by the cantonal police. They are frequently denied access to public facilities, supermarkets, or hospitals. If discovered or reported, they are either transported to remote camps or forcibly displaced. According to some interviewees, informal camps are only left for immediate border crossings or, for instance, for nighttime food procurement – food that is primarily distributed by (criminalized) volunteer aid workers.

If we need some food, two or three people would go. […] When they [the cantonal police] catch us, they drop us to Lipa Camp. Sometimes, they only beats, and then say, `Leave the city'. (Migrant from Pakistan)

We don't get bus tickets. You have to walk. […] police officers stop the buses when they see migrants in it; they have to leave the bus and they shout, `Go away.' So, you have to walk 100 kilometer. (Migrant from Afghanistan)

He [resident of an informal shelter] have blood sugar; he must have exercise – just walking around. But he can't go outside [due to the migration control measures of the cantonal police]; he don't have medicine or another option. He can't go to doctor; if he go to hospital, they ask for documents and say, `Go back to Lipa Camp. First give us permission'7. (Migrant from Pakistan)

The ambivalent relationship between the temporary and the permanent is also evident in the case of informal camps. While intended as short-term shelters, these spaces often become quasi-permanent due to repeated pushbacks, harsh winter conditions, and cantonal migration control measures. This manifests particularly in the denial of fundamental human rights, including access to adequate shelter, medical care, and sufficient food for camp residents. For those in informal camps, these legal entitlements are indirectly revoked as no sufficient alternatives are provided.

In the case of Camp Lipa, such violations of fundamental rights are even formalized as the camp exists as an extraterritorial space characterized by extreme state sanction. (In)formal camps thus function as spaces where refugees are subjected to prolonged immobilizing and marginalizing forces, leading to progressive disenfranchisement under precarious living conditions.

The migration controls and state violence described above make death an omnipresent condition of life in the border areas of the Balkans. Physical abuse; wounds; untreated infections; and lack of access to clean drinking water, food, medical care, and electricity, alongside the resulting trauma, resemble what Mbembe (2003) calls a “world of horrors and intense cruelty” (Mbembe, 2003:21) or “death worlds” (Mbembe, 2003:40). In this sense, increased migration controls have the effect of producing “new and unique forms of social existence in which vast populations are subjected to conditions of life conferring upon them the status of living dead” (Mbembe, 2003:40). These findings indicate that some migrants in the region are already trapped in a state of permanent survival within (in)formal camps, which significantly contributes to the acceptance of increasingly risky border crossings in an attempt to escape these death worlds.

However, it is crucial to emphasize that migration management along the Balkan Route is largely dictated by the European migration and border regime. As I will elaborate upon later, the widespread illegal pushbacks carried out by EU border authorities force migrants into involuntary stays within these death worlds. Moreover, so-called migration management in the region is also financially supported by the EU, with funds channeled to the International Organization for Migration (IOM). In doing so, the EU effectively establishes a parallel system of governance that operates in accordance with the logic of the European migration and border regime, which is mainly characterized by deterrence and compartmentalization (see Beznec and Kurnik, 2020:49).

4.3 Illegal pushbacks in the protection of nature

The localization and apprehension of refugees seeking asylum in European territory are primarily determined by technical border protection infrastructures that are predominantly financed by EU funds (BVMN, 2020:2). Additionally, the border management agency FRONTEX operates in the western Balkans through various missions and corresponding “training measures” (European Council, 2024). The content of these training measures is usually secretive operations.

Equipment used to control migratory movements includes border fences with NATO barbed wire and watchtowers, heart rate detectors and endoscopic cameras for checking vehicles at official border crossings, video surveillance systems with remote-controlled thermal imaging, day and night cameras combined with ground-based radar systems, and helicopters equipped with searchlights and infrared cameras (BVMN, 2020). Civilian surveillance in these landscapes has also become more prevalent, involving local forestry administrations, hunting cameras, or hikers who record people seeking protection with their mobile phones and either publish the videos on social media or send them to local authorities (Hameršak and Pleše, 2021:207ff.). Through these efforts, migrants are monitored and located even in remote areas. Using portable thermal and night-vision equipment, local border officials can then locate these groups and apprehend them on central transit routes (BVMN, 2020).

After being apprehended, migrants are taken to local police stations and interrogated for several hours. According to the individuals I interviewed, many refugees are returned to borders without an examination of their asylum claims or individual circumstances and without being provided with accommodation, interpreters, or legal assistance. Many also reported being subjected to physical violence and abuse at these informal border crossings. In most cases, personal belongings and clothing are stolen or burned in front of them. These individuals, some of whom are seriously injured, are then pushed back through informal border crossings (Themann and Etzold, 2023:535–538)8.

These informal border crossings themselves are typically located in the natural landscapes described above. These remote and peripheral locations are often scattered across vast exclusion zones. Conversations with NGOs or investigative journalists emphasized the tremendous difficulty in documenting these practices in situ. Dense forestry can also impede aerial photography, such as drone footage. These remote natural landscapes are thus used to conceal these illegal, state-organized deportation practices.

Physical abuse is rampant during these illegal pushbacks. Victims report being lined up or forced into a circle of police officers and beaten with batons, pepper spray, and improvised weapons. The nature of the terrain means that refugees who panic during this physical abuse are exposed to additional injuries:

It was a very dark place. You can't even see your feet. So, they just say to us that we have to stay in one line, and then they start to beat the people with sticks and shout, `Run!' So nobody can see what is going on or what is on the ground. If someone fell down, everyone crosses over him. People get a lot of wounds at that time when they run away from the police officers. People fell down because they don't see the way, and the way is not a straight road; the path goes downhill through a mountain area. After the pushbacks, it was really dark around us; we had no idea where we are. We had no mobile phones or stuff like that. Croatian police officers had already taken that before and burned it in a hole near the deport area. (Migrant from Afghanistan)

Illegal deportations in natural areas further add to the insecurity of injured refugees, who require considerably more time to return to (in)formal camps near the border. Moreover, repeated unsuccessful attempts to traverse Europe's external borders lead to increasing financial strain as migrants must repeatedly cover the costs of new equipment, smartphones, and migration industry services (e.g., so-called smuggling). Numerous individuals I spoke with mentioned that their financial resources had been entirely depleted as a result. This, in turn, elevates the risk of undertaking the perilous journey with inadequate equipment, devoid of local knowledge, or even alone.

I tried to cross the border but was deported. I went again and was deported again. And again. Now, I have no money for smugglers anymore. […] That's why I go by myself. (Migrant from Afghanistan)

But, you know, everyone had maybe five or six games [attempt to cross one or more borders]. Someone had 10 games. […] They got deported and came back to Bosnia. (Migrant from Kashmir)

One game costs 80–90 euros at most, including bag, food, jackets, shoes, and everything else. (Migrant from Afghanistan)

In extreme cases, these forcible expulsions can lead to the negligent death of refugees. For example, one Serbian NGO worker reported how the growing number of evacuations of informal camps along the EU's southeastern external border with Serbia has led to a shift in escape routes through Bosnia:

Since last November [2023], we have fewer refugees on the borders with Croatia, Hungary, and Romania because there have been big police actions. […] Now, all the camps have been cleared and destroyed. From Serbia to Croatia is now the most common way that refugees try to cross. It's very dangerous because of Riva Trina. It is probably the most dangerous natural barrier for refugees in Serbia. We used to get a call a week from someone who had lost someone in the river. […] Last summer, dozens of people drowned. […] And the main reason why people die is not that they are not good swimmers. […] When they get to the Bosnian side, the police catch them and then push them back, threaten them with guns, push them back into the river at night, without boats, and that's how many people lose their lives. […] That's a very tragic and unnecessary loss of life […]. Without any reason. If you want to push somebody back, you can push them back through the bridges […]. There's a big power dam, a power plant. When it's open, the current is fast. So wild. Even some people told us that when they approached the other side of the river, the police shot at their boats to damage them and drown them. […] I saw people coming back from the pushback, they were exhausted, completely wet. […] They spend a lot of time in the river at night, and they don't know which way to swim. They are just trying to survive. […] One of them told me that his brother didn't knew how to swim […]. And then the water drowned him completely. He told me that they saw the two policemen start laughing, […] and he said, `My brother died, and they were laughing.' What kind of people are they? (Interview NGO 2, Serbia)

As these testimonies illustrate, natural landscapes are central to the state's pushback machinery. They serve as surveillance space, and their remoteness shields these pushbacks from documentation. The rugged terrain is deliberately used as a deterrent, exposing those seeking protection to heightened risks of injury and death. Due to border closures, the precarious conditions in the camps, and constant evictions, refugees are often left with no choice but to flee through increasingly dangerous partial routes, which can be seen as weaponized landscapes (see above). Increased surveillance, violent pushbacks, and precarious living conditions force migrants into a struggle for survival, sometimes without financial means, adequate equipment, or local knowledge.

4.4 Migrants between extraterritorial fixation and hypermobility

As described in Sect. 4.3, the pushbacks that occur in remote natural landscapes demonstrate how physical violence, technological surveillance, and the strategic weaponization of terrain function as core mechanisms of contemporary border governance. However, these violent practices are not limited to isolated acts of expulsion; they also significantly impact the daily mobility of migrants in border regions.

The conditions that lead to death in militarized landscapes are largely shaped by the precarious living conditions in informal camps and the widespread practice of illegal pushbacks in border zones. The following section explores how these structural conditions affect migrants' mobility in the region, focusing specifically on hypermobility. As previously discussed, the extreme precariousness of migrant life stems from a combination of racialized policing in public spaces, sudden camp evictions, involuntary transfers to remote detention facilities, minimal or nonexistent state support, and the concurrent criminalization of humanitarian aid. Together, these features of state migration control severely restrict migrants' freedom of movement across the region.

However, as my findings indicate, these restrictions also result in involuntary mobility between various (informal) camps and transit sites. This forced mobility is shaped by the highly dynamic reconfiguration of transit spaces as migrants are continuously compelled to seek new shelter. For many migrants in the region, the search for adequate accommodation begins upon arrival in a new transit location – either in coordination with pre-existing network contacts or as a spontaneous response to the prevailing conditions and the most up-to-date information available:

This is an old building [informal shelter in an old retirement house], all migrants know it. My friends, they come before me [to Bosnia]. When we cross the border […] they call us, and said, `You have to come to Bihać, there is camp' [formal camp in the region]. But at this time, they don't distribute ID cards in the camp. So, they show me this building and said, `Please come, we live here.' We are all friends, we lived together in Serbia before. That's why they show me that building. (Migrant from Pakistan)

No. I don't know that place [informal shelter in Bosnia] before. I came here, and I saw that the situation was very bad. […] I couldn't go in the main camp; it was full. […] Some people stayed here, and I heard this. […] Then I came here. (Migrant from Bangladesh)

The high degree of flexibility required in the search for (informal) camps is not only important upon initial arrival; it is also continuously renegotiated throughout one's stay. This applies, for instance, when returning after an unsuccessful attempt to cross the European external border but can also be shaped by migration control measures of the local police:

Bosnian police […] catch us [in the last informal shelter] and take everything. Mobile phone, power bank, and money. […] They take everything. When they come the last time, we run away from there, and we decide to leave and search a new shelter. (Migrant from Afghanistan)

We were on game, then they [Croatian border guards] pushback us, and when we came back, the main camp was already closed [by authorities]. So, we decide to live here [in a new informal camp in the region]. (Migrant from Iran)

Based on my interviews and observations, I argue that these actions are designed to make the stay of migrants as exhausting, unsafe, uncomfortable, and unpredictable as possible through arbitrary controls. As a result, migrants are kept on the move as part of a policy of deterrence, removed from the visible parts of transit points, and thus forced to constantly adapt to the changing conditions of migration controls. This manifests in the increasing immobilization of refugees while simultaneously causing their involuntary mobility between different (in)formal camps. Once migrants attempt to escape this situation and continue their journey toward northern and western Europe, they are violently pushed back to the same transit routes or die attempting to cross the borders.

Migrants moving through the border spaces along the Balkan Route thus find themselves in a constant state of survival in order to withstand the enormous burdens inflicted by migration controls:

These people are in fight or flight mode, probably for 3 years, because that's how long it takes you sometimes to reach this border. And you are in the psychological warfare of constantly being in tense survival mode through the violence of the police. You finally cross the border, and they push you back. You cross it again, and they push you back and beat you. The local community hates you; they literally make committees so they can harass you. (Interview NGO 1, Serbia)

My findings also indicate that the question of how to deal with increasing migratory movements is not answered by strengthening migration controls. Rather, increased migration controls tend to place migrants along the Balkan Route in precarious and life-threatening situations, leading to their hypermobility. This hypermobilization significantly contributes to refugees choosing even riskier routes to enable their clandestine escape to western or northern Europe. As one NGO worker in Serbia put it,

By creating barriers to accessing the European Union, you're not preventing people from coming. You're just killing them along the way. (Interview NGO 1, Serbia)

In this article, I have examined the complex interplay between natural landscapes, state violence, and mobility along the Balkan Route. I refer to these landscapes as weaponized landscapes because they function not only as physical barriers but also as instruments of violence, surveillance, and deterrence actively used by state actors. Consequently, rivers, forests, and mountains are integrated into the European border regime. Through the refusal of aid, strategic inaction, and criminalization of humanitarian support, these landscapes are re-purposed into instruments of exclusion and death. What are typically perceived as “natural” terrains thus become politically charged spaces where migration policy failures and state violence intersect with fatal consequences.

(In)formal camps along vital transit points of the Balkan Route, as well as pushbacks by border officials, are key preconditions for the deaths of migrants in these environments. These camps are not static storage facilities; rather, they are dynamic spaces in which migrants are forced to remain under precarious conditions, caught between forced mobility and immobility. Additionally, migrants are repeatedly pushed back into these spaces through illegal expulsions, driving many to attempt even riskier border crossings. Held on the threshold between life and death, the inhabitants of (in)formal camps and those affected by pushbacks face conditions in which their deaths along these routes are accepted if not actively encouraged. Weaponized landscapes are thus more than abstract border spaces; they are real worlds of death in which those seeking protection suffer and die at great risk.

Against this backdrop, the function of natural landscapes as active instruments of state control and violence can be clarified by expanding existing research approaches to border violence. In addition to technical and legal border security mechanisms, weaponized landscapes highlight how these violent spaces enable surveillance, deterrence, and the physical exclusion of people seeking protection. At the same time, they obscure state violence, making documentation and accountability more difficult. By embedding state violence within specific physical and natural conditions, the border area emerges as a hybrid space where the environment, technological surveillance, and state violence intertwine. This perspective can strengthen the incorporation of the natural and physical dimensions of state violence into existing debates on border regimes and forced migration.

It also becomes clear that migration control along the Balkan Route is characterized by the paradoxical coexistence of voluntary and forced mobility. Restrictive border policies lead to hypermobility, which goes beyond conventional concepts of mobility and immobility. Hypermobilization is a state of restrictive migration control that places migrants in a state of permanent exhaustion, insecurity, and forced mobility. Migrants are constantly relocated between formal and informal camps, which simultaneously serve as spaces of fixation and surveillance. This dialectic of mobility and hypermobility deserves greater attention in geographical migration research as it allows forced migration to be seen not only as unidirectional movement but also as a complex process shaped by power dynamics that keep migrants in a constant state of exhaustion and insecurity.

The connection between natural landscapes, state violence, and (im)mobility contributes to the empirical documentation of illegal border protection practices and opens new avenues for understanding border regimes and state violence. This connection reveals how natural landscapes, high-tech border control infrastructure, and internment in camps interact as key components of state migration control. These components profoundly shape the mobility of individuals seeking protection, often resulting in an existential threat or death.

The research data are not available in order to mitigate the potential risks to which research participants might be exposed if they were to travel to western and northern Europe.

The author has declared that there are no competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

I would like to express my gratitude to all of the interview participants for providing insight into their daily lives and for extending such a cordial welcome. Additionally, gratitude is extended to the NGOs for their relentless efforts at Europe's external borders and to the editors for their insightful comments, which have played a pivotal role in ensuring the article's rigor and relevance.

This paper was edited by Lucas Pohl and reviewed by two anonymous referees. The editorial decision was agreed between both guest editors, Lucas Pohl and Jan Hutta.

4D: Deceased, disappeared, detained – documenting migrant trail in the Balkans, https://4dtrail.wordpress.com/database/ (last access: 6 November 2025), 2025a.

4D: Deceased, disappeared, detained – documenting migrant trail in the Balkans, https://4dtrail.wordpress.com/about/ (last access: 6 November 2025), 2025b.

Agamben, G.: Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, ISBN 0804732183, 1998.

Aradau, C. and Tazzioli, M.: Biopolitics Multiple: Migration, Extraction, Subtraction, Millenium, 48, 198–220, https://doi.org/10.1177/0305829819889139, 2019.

Bank, A., Christiane, F., and Schneiker, A.: The Political Dynamics of Human Mobility: Migration out of, as, and into Violence, Global Policy, 8, 12–18, 2017.

Beznec, B. and Kurnik, A.: Old routes, new perspectives: The Frontier Within: The European Border Regime in the Balkans, 5, 33–54, 2020.

Breuckmann, T.: Too little to live, too much to die: governing asylum seekers on the brink of death in Moria, Lesvos, Geogr. Helv., 80, 191–202, https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-80-191-2025, 2025.

Brun, C.: Active Waiting and Changing Hopes: Toward a Time Perspective on Protracted Displacement, Social Analysis, 59, 1, 19–37, 2015.

Brun, C. and Fábos, A.: Making Homes in Limbo? A Conceptual Framework, Refugee, Canada's Journal on Refugees, 31, 5–17, 2015.

Buckel, S. and Wissel, J.: State Project Europe: The Transformation of the European Border Regime and the Production of Bare Life, International political sociology, 4, 33–49, 2010.

BVMN: The Role of Technology in Illegal Push-backs from Croatia to Bosnia-Herzegovina and Serbia, Border Violence Monitoring Network, https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Racism/SR/RaceBordersDigitalTechnologies/Border_Violence_Monitoring_Network.pdf (last access: 7 April 2024), 2020.

Davies, T., Isakjee, A., and Dhesi, S.: Violent Inaction: The Necropolitical Experience of Refugees in Europe, Antipode, 49, 1263–1284, 2017.

De Genova, N.: The Borders of “Europe”: Autonomy of Migration, Tactics of bordering, Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11smr05, 2017.

De León, J.: The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail, University of California Press, Oakland, California, https://doi.org/10.1525/j.ctv1xxvch, 2015.

Dines, N., Montagna, N., and Ruggiero, V.: Thinking Lampedusa: Border Construction, the Spectacle of Bare Life and the Productivity of Migrants, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 38, 430–445, 2015.

Estévez, A: The necropolitical production and management of forced migration. Rowman & Littlefield, London, ISBN 1793653291, 2022.

Etzold, B.: Auf der Flucht: (Im)Mobilisierung und (Im)Mobilität von Schutzsuchenden. State of research Papier 04, Verbundprojekt Flucht: Forschung und Transfer', Osnabrück, Institut für Migrationsforschung und Interkulturelle Studien (IMIS) der Universität Osnabrück/Bonn International Centre for Conflict Studies (BICC), Bonn, Germany, 2019.

European Council: Border Management: Agreements with Non-EU Countries, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/border-management-agreements-third-countries/ (last access: 7 April 2024), 2024.

Foucault, M.: In Verteidigung der Gesellschaft: Vorlesungen am Collège de France (1975–1976), Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, ISBN 978-3-518-29185-6, 1999.

Gao, Q., Woods, O., and Kong, L.: The political ecology of death: Chinese religion and the affective tensions of secularised burial rituals in Singapore, Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 6, 537–555, 2023.

Gebhardt, M.: To Make Live and Let Die: On Sovereignty and Vulnerability in the EU Migration Regime, Redescriptions, 23, 120–137, 2020.

Grenfell, P., Stuart, R., Eastham, J., Gallagher, A., Elmes, J., Platt, L., and O'Neill, M.: Policing and public health interventions into sex workers' lives: necropolitical assemblages and alternative visions of social justice, Critical public health, 33, 282–296, 2023.

Hameršak, M. and Pleše, I.: Weaponized Migration Landscapes at the Outskirts of the European Union, Etnološka Tribina, 51, 204–221, 2021.

Heimeshoff, L., Hess, S., and Kron, S.: Grenzregime II: Migration, Kontrolle, Wissen. Transnationale Perspektiven. Assoziation A., Berlin, Germany, ISBN 978-3-86241-432-1, 2014.

Hess, S. and Kasparek, B.: Grenzregime: Diskurse, Praktiken, Institutionen in Europa, Assoziation A., Berlin, Germany, ISBN 978-3-935936-82-8 , 2010.

Hess, S., Kasparek, B., and Kron, S.: Der lange Sommer der Migration. Grenzregime III, Assoziation A., Berlin, Germany, ISBN 978-3-86241-453-6, 2017.

IOM: Mixed Migratory Flows in the Western Balkans, https://dtm.iom.int/datasets/europe-mixed-migration-flows-europe-quarterly-overview-oct-dec-2022 (last access: 6 November 2025), 2023.

Johannes, D.: Desert and Death: Biopolitical Landscapes and Affect in US-Mexico Border Representations, Dissertation, Arizona, https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/581327 (last access: 6 November 2025), 2017.

Jordan, J. and Moser, S.: Researching migrants in informal transit camps along the Balkan Route: Reflections on volunteer activism, access, and reciprocity, Area, 52, 566–574, 2020.

Khosravi, S.: Afterword. Experiences and stories along the way, Geoforum, 116, 292–295, 2018.

Klikactive: The end of the road, https://klikaktiv.org/journal/the-end-of-the-road (last access: 6 November 2025), 2023.

Kreichauf, R.: From Forced Migration to Forced Arrival: The Campization of Refugee Accommodation in European Cities, Comparative Migration Studies, 6, 1–22, 2018.

Lighthouse Reports: Europe's nameless dead, https://www.lighthousereports.com/investigation/europes-nameless-dead/ (last access: 6 November 2025), 2023

Manek, J.: No Camp is a “Good Camp”: The Closed Controlled Access Centre on Samos as a Torturing Environment and Necropolitical Space of Uncare, Antipode, 57, 324–349, 2024.

Martin, D., Minca, C., and Katz I.: Rethinking the Camp: On Spatial Technologies of Power and Resistance, Progress in Human Geography, 44, 743–768, 2019.

Mbembe, A.: Necropolitics, Public Culture, 15, 11–40, https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-15-1-11, 2003.

Minca, C., Šantić, D., and Umek, D.: Walking the Balkan Route, Camps revisited, 35–59, https://doi.org/10.5040/9798881810061.ch-003, 2018.