the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Mapping climate-change-related processes affecting most frequented routes by French mountain guides

Xavier Cailhol

Ludovic Ravanel

Jacques Mourey

This paper examines the impact of climate change on alpinism in the western European Alps, focusing particularly on the routes most frequently used by French mountain guides. The aim is to identify the geomorphological and glaciological processes affecting these routes and to evaluate how these changes impact guiding practices. Two complementary approaches were employed. First, a survey of the French Mountain Guides Association (SNGM) was conducted to identify the 24 most frequented routes used by French mountain guides between 2017 and 2022. Semi-structured interviews were then conducted with guides and hut keepers to recognise 24 climate-related processes, which were then compared with the iconic itineraries detailed in Gaston Rébuffat's classic guidebooks. The analysis shows that the most frequented routes are affected by an average of seven glaciological or geomorphological processes, compared to nine for the historic routes. Itineraries involving high-altitude and mixed terrain are particularly exposed to glacier retreat, permafrost degradation and rockfalls. In response, guides are adopting various strategies, such as abandoning the most dangerous routes, choosing safer alternatives and scheduling ascents for spring or autumn. They are also temporarily suspending climbing some routes during heat waves. These adaptations illustrate the emergence of a culture of adaptation to climate change within the guiding profession. However, the discussion also highlights persistent tensions. While high-altitude alpinism remains central to the cultural identity of guides, it is also becoming increasingly risky. Meanwhile, the shift towards mid-altitude routes is creating conflicts with other land users and raising ecological issues. The long-term sustainability of these adaptations is unclear, particularly in light of the hardly predictable effects of cryosphere evolution. French mountain guides are at the forefront of this transition through mobility and innovation. Supporting their adaptive strategies is crucial to preserving both the safety of high-altitude guiding and its cultural significance.

- Article

(13857 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

During the 1960s, alpinism was primarily undertaken in summer, with winter ascents being considered extremely challenging. For example, the Eiger north face was primarily climbed in summer in the 1960s and 1970s. However, contemporary alpinism has shifted towards the winter and spring seasons, driven by the desire to mitigate risk and minimise exposure to rockfalls. This assertion also applies to traditional alpinism routes. Gaston Rébuffat's book series Les 100 plus belles courses (The 100 most beautiful climbs; Rébuffat, 1973, 1974, 1979), featuring routes in the Valais, Mont Blanc and Écrins massifs, illustrates this shift. Two-thirds of the featured routes are no longer accessible during the summer months (Mourey et al., 2019b; Mourey et al., 2022a; Arnaud et al., 2024).

Indeed, high Alpine environments are experiencing a faster rise in temperatures than the global average. For example, the European Alps have experienced a warming trend of over 0.3 °C per decade recently, which is 0.1 °C higher than the global average (IPCC, 2022).

This warming has led to the rapid degradation of the Alpine cryosphere (Huss et al., 2017; Noetzli et al., 2024). Glacier surfaces in the Swiss Alps decreased by 28 % between 1973 and 2010 (Fischer et al., 2014), while in the French Alps, they decreased by 25 % between 1967 and 2009 (Gardent et al., 2014). There has been an acceleration in melting since the 1990s (Huss, 2012; Vincent et al., 2017). Between 2000 and 2023, the volume of glaciers in the Alps decreased by 38.7 % (The GlaMBIE Team, 2025). Following the two exceptionally warm summers of 2022 and 2023, Swiss glaciers lost over 10 % of their mass within 2 years (Swiss Academy of Sciences data; Huss et al. 2025). At the same time, glacier fronts retreated dramatically. Between 1880 and 2015, the Argentière glacier (Mont Blanc massif, France) retreated by 1100 m, while the Aletsch glacier (Switzerland) retreated by 2200 m (World Glacier Monitoring Service (WGMS), 2015; Beniston et al., 2018). This retreat has accelerated since the early 2000s; for example, the front tongue of the Mer de Glace (Mont Blanc massif) retreated 400 m between 2003 and 2014 (Vincent et al., 2014), while the Zinal glacier (Switzerland) retreated 400 m between 1990 and 2018 (Glacier Monitoring in Switzerland (GLAMOS), 2020). Glacier retreat on steep slopes can lead to hanging tongues falling and an increased frequency of ice avalanches (Fischer et al., 2006; Failletaz et al., 2015).

On annual and secular timescales, ice avalanches occur primarily during the warmest periods (Deline et al., 2012). Glacial retreat also leads to an increase in the surface area and/or thickness of supraglacial debris cover on some glaciers (Gomez and Small, 1985; Scherler et al., 2018).

Another consequence of climate change is a reduction in snow cover on glaciers, i.e. an increase in the altitude of the glacier equilibrium line (Rabatel et al., 2013; Beniston et al., 2018). This results in the shrinkage of snow bridges covering crevasses (Ravanel et al., 2022). Together with a reduction in refreezing periods (Pohl et al., 2019) and an increase in the altitude of the 0 °C isotherm (Scherrer et al., 2021), this results in snow bridges weakening earlier in spring or during heat waves (Ravanel et al., 2022).

In high Alpine environments, the most frequent paraglacial processes are rockfalls and landslides from recently deglaciated rock walls and moraines (Mercier, 2008; McColl, 2012; Deline et al., 2015; Draebing and Eichel, 2018; Eichel et al., 2018; Ravanel et al., 2018; Hartmeyer et al., 2020). Rockfalls can also be linked to permafrost warming (Ravanel et al., 2013; Ravanel et al., 2017; Legay et al., 2021; Magnin et al., 2024). Rockfalls can be relatively small in volume (V<100 m3), posing a danger to alpinists, or very large, reaching several million cubic metres. These major rockfalls trigger cascading processes, for example, the rockfall at Piz Scerscen (3970 m above sea level) in 2024 and the rockfall at Kleine Nesthorn (3341 m) in 2025, which destroyed the village of Blatten (both in Switzerland). These events began with a rockfall and then caused an ice avalanche when the rockfall reached the underlying glacier. This configuration results in a significant influx of liquid water due to the liquefaction of the ice, causing the rockfall debris to spread farther within a debris flow.

High-altitude Alpine environments are therefore currently experiencing significant changes. Alpine routes have undergone significant changes since the 1970s (Purdie and Kerr, 2018; Mourey et al., 2019b, 2022a; Hanly and McDowell, 2024). A total of 26 processes affects alpinism routes in the European Alps (Mourey et al., 2019b, 2022a; Arnaud et al., 2024; Cailhol et al., 2025).

This study aims to describe, understand and quantify the impact of climate change on the current practices of French mountain guides, by identifying and studying their most frequently used routes during the summers of 2017–2022 (referred to here as the “repertoire of the most frequently used routes”). It was also necessary to compare the effects of climate change on these routes with those on a selection of iconic alpinism routes from the 1970s, as presented in reference books such as the collection by Rébuffat and as extracted from previous studies (Mourey et al., 2019b, 2022a; Arnaud et al., 2024). A comprehensive analysis of 216 distinct routes provides an in-depth understanding of the influence of climate change on alpinism and enables the design of innovative strategies to sustain the activity. This comparison enables us to understand the differences between mountain massifs and to compare the impact of climate change in different locations in the Alps. The geomorphological and glaciological information provided by the mapping allows alpinists to objectively identify changes to their regular routes. This also enables more experienced alpinists to recall these changes and helps younger climbers to overcome the phenomenon of ecological amnesia by understanding the initial state of the routes.

The study employs two complementary methods of data collection. The first is a quantitative survey that uses a comprehensive questionnaire to identify the most frequently climbed alpinism routes by French mountain guides, who will be referred to as French Mountain Guides Association (SNGM) guides in the following. The second method involves mapping processes linked to climate change affecting alpinism routes, as well as analysing their evolution. This is conducted through semi-structured interviews.

2.1 Rébuffat guidebook's collection analyse

In accordance with Mourey et al. (2019b, 2022a) and Arnaud et al. (2024), all the routes were studied according to the same methodology.

A selection of the primary routes delineated in the guidebook will be used, along with a series of interviews designed to map geomorphological and glaciological changes. The following two fundamental research questions will be addressed by the present series of interviews. The following questions are hereby posed for investigation. First, what are the ongoing long-term changes on the itineraries since the 1970s? Second, the manner in which these itineraries have evolved with respect to technical complexity, inherent risks and optimal periods for ascent should be examined.

The preliminary study phase enabled the authors to identify and map all the geomorphological and glaciological processes that affect the alpinism routes described in the book. A second set of interviews was then conducted to verify the mapped elements and define them. The global evolution of the climbing parameters of each itinerary was evaluated using a 5-level scale. The parameters encompassed by this categorisation include the nature of the terrain, such as ice, snow, mixed terrain (ice and rock); the technical complexity of the route; the level of exposure to objective dangers; and any modifications to the optimal period for the ascent. The latter is defined as the time when the number and intensity of changes affecting the route are at their lowest. The aforementioned changes resulted in the subsequent categorisation of itineraries:

-

Level 0. The itinerary and the parameters determining how it is climbed have not changed.

-

Level 1. The itinerary and its climbing parameters have slightly evolved. Only a short section of the itinerary is affected by geomorphic and cryospheric changes, and this does not result in a significant increase in objective dangers and/or in technical difficulty.

-

Level 2. The itinerary and its climbing parameters have moderately evolved. The optimal periods for the ascent have become rare or unpredictable in summer and shifted towards spring, fall and winter. Risks and technical difficulty are increasing, and alpinists therefore have to adapt their technique.

-

Level 3. The itinerary and its climbing parameters have greatly evolved. Generally, the itinerary can no longer be climbed in summer. Risks and technical difficulty have greatly increased due to the number and intensity of the geomorphic changes affecting it. Alpinists have to fundamentally change the manner in which they climb the itinerary.

-

Level 4. The itinerary has mostly disappeared. The itinerary can no longer be climbed.

Further details on the methodology can be found in Mourey et al. (2019b, 2022a).

2.2 Survey method

In order to ascertain the most frequently used routes by French mountain guides and to understand their relationships with the routes they use, a survey composed of 44 questions was distributed on 20 April 2022 to 1300 French mountain guides, all members of the Syndicat National des Guides de Montagne (SNGM), with two reminders. The guides were granted a period of 1 month in which to furnish a response.

The survey is structured into four main sections in order to ensure comprehensive data collection.

The initial section is dedicated to the comprehension of the guiding profession, with a focus on the profiling of respondents in terms of their years of experience, primary periods of professional activity, types of supervised activities and employment status. The following questions are employed: to ascertain the experience of the mountain guide, it is first necessary to establish the length of time they have been working. Furthermore, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the guide's areas of expertise, it is also important to ascertain the guiding activities they are most frequently engaged in. This section facilitates the delineation of the distinctive characteristics and professional practices of various types of guides.

The second section facilitates the delineation of the most frequently visited massifs and routes by French guides. The study thus provides insights into the perceived territoriality of their professional activities, with questions such as: to ascertain the most frequently visited massifs over the past 5 years, and to determine the level of the routes climbed most often, a survey is required. The study also examines the tools that guides use to select and prepare routes, thereby shedding light on the methods and criteria employed for route planning.

This section further investigates the routes most frequently guided over five summers (2017–2022), allowing for an analysis of trends while accounting for annual variations. For example, the notably “cold and snowy” summer of 2021 displayed favourable conditions compared to the preceding and following years. In the course of the survey, guides were questioned on approximately three types of routes: the three route categories under discussion are as follows: (1) “Contemporary Routes”, reflecting current practices shaped by climate change; (2) “Heritage Routes”, embodying traditional values of alpinism; and (3) “Abandoned Routes”, illustrating short-term shifts in guiding practices. The concluding section of this study examines the duality of the guide–client relationship and its influence on the construction of the guiding profession.

The third section of the survey examines changes in the primary repertoire of routes through the lens of climate change. This section will not be covered in this study.

The fourth section of this study focuses on defining the sociological profile of the guides. The survey collects data on respondents' place of residence, age and territorial distribution, thereby providing insights into the geographic and demographic patterns that characterise the guides. The integration of these dimensions within this section fosters a comprehensive understanding of the profession's trends and challenges, particularly in relation to the warming trend. The findings contribute to the definition of adaptation strategies, the enhancement of training programmes and the fostering of discussions on the evolving role of mountain guides as mediators of environmental changes.

The present article will focus on the results from the second section of the survey, which was dedicated to the routes and massifs classically frequented by French mountain guides.

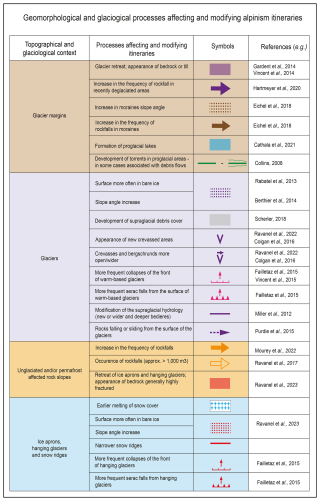

2.3 Semi-directive interviews to map geomorphological and glaciological processes linked to climate change

The second part of this study focuses on the impact of climate change on the routes most frequently used by French high-mountain guides. The result of this research was a comprehensive mapping of the geomorphological and glaciological processes associated with climate change along these routes. The methodology employed in this study was developed by Mourey et al. (2022a). The methodology of mapping is based on the analysis of the evolution of alpinism routes over the long term in order to describe the impacts of climate change from the 1970s to the present day. The 26 different geomorphological and glaciological processes that affect alpinism routes in the European Alps have been identified (Mourey et al., 2019b; Arnaud et al., 2024). The mapping of these features is facilitated by 22 symbols, which draw inspiration from the geomorphological legend of the University of Lausanne (Schoeneich, 1993; Lambiel et al., 2016). The application of these symbols facilitates the identification of 24 distinct processes; however, the “Weakening of snow bridges” (Ravanel et al., 2022) and “Less frequent night frost” (Pohl et al., 2019), as observed in the Mont Blanc massif (Mourey et al., 2019b), were not addressed in the present study. The process entitled “An earlier melting of snow cover and firn” (Arnaud et al., 2024) is otherwise here considered. The processes entitled “Glacier surfaces more often in bare ice” (Ritter et al., 2012; Purdie and Kerr, 2018; Mourey et al., 2019b, 2022a) and “Increase in the slope angle in a part of the glacier” (Dobhal, 2010; Berthier et al., 2014) are almost always associated (same symbol). These terms refer to the processes described by Mourey et al. (2019b, 2022a). As stated in the literature, descriptions in guidebooks and interviews indicate that certain sections of the routes are exposed earlier in the summer season. This revelation has significant implications for alpinists, as it reveals the glacier ice, steeper slopes and gradual erosion of the route year on year. This progression is further compounded by the increased difficulty in negotiating the route. The same approach is applied to the processes “Ice apron more often bare ice” and “Increase in a part of ice apron slope angle” (Ravanel et al., 2023). The 24 mapped processes have been classified into four categories according to the terrain on which they are located: (i) glacial margins; (ii) glaciers; (iii) rock slopes that are not glaciated; and (iv) ice aprons, hanging glaciers and snow slopes.

The initial phase of the mapping process involves conducting semi-directive interviews with high-mountain socio-professionals. In this study, 25 interviews were conducted with local mountain guides and refuge keepers, with the same researcher conducting each interview. The interviews lasted 1–2 h. The selection of socio-professionals for these interviews was made on the basis of their extensive knowledge of the study routes. It is evident that all of the professionals interviewed have accumulated extensive experience working on one or more of these routes.

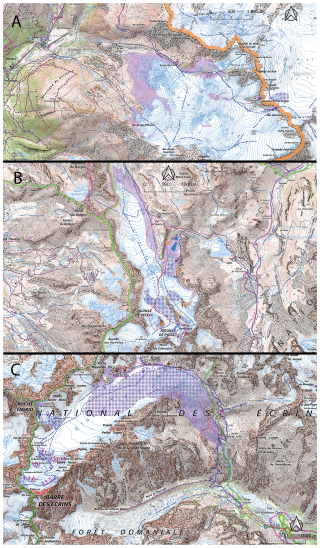

Geomorphologic analysis

The data obtained from the interviews were integrated into a geographic information system (GIS, here QGIS) to create a preliminary layer of mapping, which was then accompanied by an analysis of historical aerial images (from 1940) and current aerial images (up to 2020). The analysis also incorporated historical topographic maps (scans 50 of 1950 from the Institut Géographique National, or IGN) and a digital elevation model, such as the HD LiDAR from IGN or swissSURFACE3D from Swisstopo (Mourey et al., 2022a). The most recent aerial images facilitate the accurate digitisation of glaciers and ice aprons, as well as certain debris cover on glaciers. The development of torrents in proglacial areas and the presence of proglacial lakes are also digitised using current aerial images. The organisation occasionally conducted field trips for the purpose of confirming the precise location of certain processes, such as the limits of the debris-covered glaciers. In order to finalise the maps, a second series of interviews was carried out with 10 other socio-professionals (mountain guides) who had not been interviewed in the first step. The cartographic representations were produced at a scale of 1:25 000, and interviewees were invited to confirm, clarify or refute the processes mapped (Fig. 1).

3.1 Previous results from Les 100 plus belles courses

Using the renowned topo-guides from Rébuffat's collection, Les 100 plus belles courses, Mourey et al. (2019b, 2022a) and Arnaud et al. (2024) have meticulously mapped a substantial proportion of the routes featured in these publications. A total of 95 routes were analysed in the Mont Blanc massif: 36 in the Valais region and 70 in the Écrins massif. A closer analysis of the most frequently used routes by French mountain guides reveals that only 10 of these routes are included in the aforementioned list. The evidence presented indicates that, despite the fact that the routes delineated in these guidebooks were regarded as essential objectives in the 1980s, the majority of them are currently eschewed by French mountain guides in their primary professional practice. This is predominantly attributable to the repercussions of climate change.

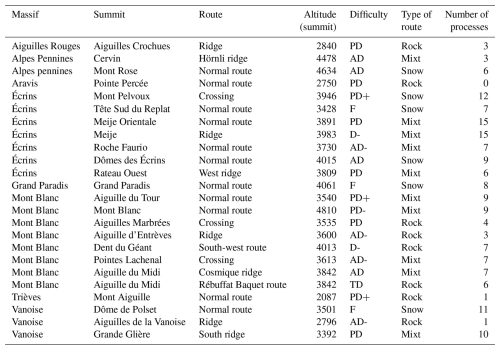

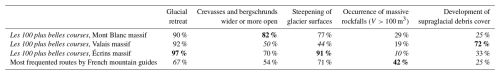

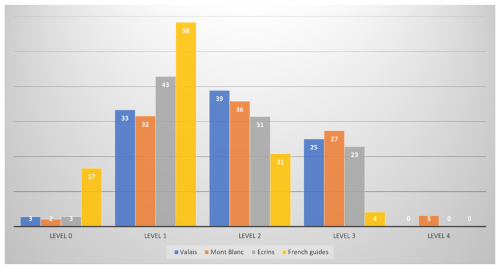

3.1.1 Mont Blanc massif

In the Mont Blanc massif, on average, an itinerary is affected by nine geomorphological and glaciological processes (Mourey et al., 2019b). As illustrated in Table 2, 90 % of the routes are affected by the presence of bedrock, 82 % by the widening of crevasses and rims, and 77 % by the steepening of glacier slopes. In relation to the evolution scale employed to assess alterations to the itineraries under scrutiny, two have remained static (Level 0), 30 have undergone minor evolution (Level 1), 34 have exhibited moderate evolution (Level 2), 26 have undergone substantial evolution (Level 3) and three have been eliminated (Level 4). Furthermore, a direct correlation has been demonstrated between the number of changes affecting an itinerary and its level of evolution. The mean number of changes affecting itineraries is 7.4 for Level 1, 10 for Level 2, 11.5 for Level 3 and 12.5 for Level 4.

3.1.2 Valais

In the Valais massif (Mourey et al., 2022a), on average, an itinerary is affected by nine geomorphological and glaciological processes. The retreat of ice aprons and hanging glaciers has an effect on 92 % of the routes. It is evident that ice aprons, characterised by their absence of snow and steeper inclines, are present in 67 % of the observed routes. The development of a supraglacial debris cover has been observed to affect 72 % of the routes. An increase in the frequency of rockfalls on unglaciated rock slopes affects 72 % of the routes, and an increase in the frequency of rockfalls in recently deglaciated areas affects 53 % of the routes (see Table 2 for details).

In relation to the evolution scale employed to assess alterations to the itineraries, one (3 %) has remained constant (Level 0), 12 (33 %) have undergone minor evolution (Level 1), 14 (39 %) have exhibited moderate evolution (Level 2), nine (25 %) have undergone substantial evolution (Level 3) and none have been eliminated (Level 4). Furthermore, a direct correlation has been demonstrated between the number of changes affecting an itinerary and its level of evolution. The mean number of changes affecting itineraries was 7.5 for Level 1, 9.4 for Level 2, and 11.2 for Level 3.

3.1.3 Écrins massif

In the Écrins massif (Arnaud et al., 2024), it was found that each route is affected by an average of nine different processes. The routes are primarily influenced by glacier retreat (97 %), steeper glaciers (91 %) and glaciers that experience earlier snow clearance in the summer season (91 %) (see Table 2 for details).

In relation to the evolution scale employed to assess alterations to the itineraries examined from an alpinism perspective, two (3 %) have remained constant (Level 0), 30 (43 %) have undergone minor evolution (Level 1), 22 (31 %) have exhibited moderate evolution (Level 2), 16 (23 %) have demonstrated substantial evolution (Level 3) and none have been eliminated (Level 4). Furthermore, a direct correlation has been demonstrated between the number of changes affecting an itinerary and its level of evolution. The mean number of changes affecting itineraries is as follows: 1 for Level 0, 6 for Level 1, 12 for Level 2 and 13 for Level 3.

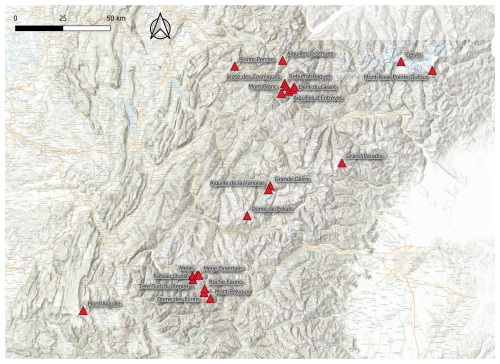

3.2 Routes most frequented by French mountain guides

The inventory of the most frequently visited routes by French mountain guides was compiled by means of an analysis of the survey that was distributed to SNGM guides in spring 2022. The survey received 130 responses, constituting 10 % of the guides affiliated with the union. The typology of respondents corresponds to the general guide profile identified thanks to a trade survey carried out in 2020 by SNGM, considering the location (department of residency) and the seniority of guides. The representativeness of the sample with respect to the base population has been assessed using χ2 goodness-of-fit tests (Laurencelle, 2012). The selected routes were cited by at least three different guides as being among the “Five most frequented routes over the last 5 years” for them. A total of 24 routes were identified (see Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Table 1Most frequented routes by French mountain guides between 2017 and 2022. The difficulty level is designated by the overall Alpine rating scale, ranging from F for “Facile” (easy) to TD for “Très Difficile” (very difficult). The number of processes corresponds to the number of different geomorphological or glaciological processes that affect each route.

3.2.1 Geomorphological and glaciological processes affecting the most frequented routes

The most frequently used routes are affected on average by seven geomorphological or glaciological processes linked to climate change. The number of processes is contingent on the massif: the number of processes per route in the Mont Blanc massif is 6.5, in the Valais 4, in the Écrins 10, and in the Vanoise 10.5.

The six processes with the greatest impact on the routes are as follows: an increase in the slope angle of glaciers (71 %), more frequent occurrence of bare ice on the glacier surface (71 %), glacier retreat (67 %), an increase in the frequency of rockfalls < 100 m3 (63 %), more wide-open crevasses (54 %) and an increase in occurrence of rockfalls > 100 m3 (42 %) (Table 2). The altitudinal range in which these processes occur is from 2000 to 4700 m a.s.l. The highest process that has been mapped so far corresponds to a steepening of the glacier surface beneath the summit of Mont Blanc (4806 m). The lowest process mapped corresponds to the development of a proglacial torrent in Pré de Madame Carle (Ailefroide, Écrins massif, France).

Table 2Comparative analysis of the main processes that affect the routes studied. In bold: the routes issued from the selection (i.e. Les 100 plus belles or most frequented by French mountain guides) are the most affected by the process. In italics: the routes of the selection are those that are less affected by the process studied.

Figure 3Map of the effects of climate change on (A) Aiguille du Tour (3540 m a.s.l., Mont Blanc massif, France) normal route, (B) Dome de Polset (3501 m a.s.l., Vanoise massif, France) normal route and (C) Glacier Blanc bassin (Écrins massif, France) including the highest summit of the massif with Barre des Écrins (4101 m a.s.l.). Base map: IGN.

3.2.2 The degree and type of evolution for an itinerary depends on the nature of the terrain and the altitude

In general, mixed routes (combining ice, snow and rock elements) demonstrate an average influence from 10 processes, while snow routes exhibit an average impact from nine processes and rock routes display an average effect from three processes.

3.2.3 Altitudinal gradation

An altitudinal gradation is evident in the processes affecting the routes. At lower altitudes, alpinists are confronted with processes such as the development of debris flows or proglacial lakes, which are primarily the result of glacier retreat. At an altitude of approximately 2500 m a.s.l., the glacier fronts, which have been retreating since the 1980s, are reached. This retreat is characterised by the presence of extensive sections where alpinists undertake ascents on bedrock that is predominantly compact or on moraines that have not yet undergone stabilisation. Upon arriving at the glacier, alpinists must confront a variety of processes, including the accelerated clearance of snow from glacier surfaces and the formation of steep ice slopes. Additionally, the presence of supraglacial debris and the movement of rock materials across the glacier's surface must be taken into account. The reduction in snow cover along the routes has also been observed to result in the earlier emergence of wider crevasses during the early stages of the season. At elevations above 3000 m, alpinists must contend with the risk of rockfalls, precipitated by the warming permafrost and/or glacier retreat. The volume of rockfalls can vary significantly, ranging from less than 100 m3 to greater than 100 m3, contingent on the selected itinerary and the geological characteristics of the route.

Routes starting between 1000 and 2000 m a.s.l. are affected on average by nine different processes, while routes starting at 2000 m a.s.l. are affected on average by five different processes and by six processes for those that start above 3000 m a.s.l.

3.3 Complementary inventory of French mountain guides' practice

The survey also examined the routes that guides have abandoned in recent years due to the effects of climate change (according to their interpretation) and those they consider to be iconic. The term “iconic routes” is employed to denote those that every guide is presumed to have ascended with a client at some point during the course of their career. The reasons for their iconic status are twofold. First, the subject's status as iconic is attributable to the cultural history of alpinism they embody. Second, they are considered iconic due to the “quality” of the climbing experience they offer.

3.3.1 The abandoned routes

In response to the query regarding the routes that are no longer climbed due to climatic considerations, the routes cited by the guides offer a discerning insight into the evolving perceptions concerning the repercussions of climate change on alpinism.

The Dôme and Barre des Écrins (which are located in the Écrins massif and have an altitude of 4015 and 4102 m a.s.l., respectively) are in first and fifth place. These two routes, which shared a common segment, were subsequently abandoned following a series of serac falls along the route. The Bureau des Guides des Écrins has decided to suspend the sale of “collective ascents” of these routes. The classic Mont Blanc routes on the French side of the eponymous massif, i.e. the three Monts (16 % of respondents) and the Goûter routes (26 % of respondents), are mentioned by guides as routes they no longer climb. This suggests a significant divergence of opinion between guides regarding the Goûter route. Some consider it to be the route they most often climb, while others have declined to climb it due to climatic reasons. It is evident that the Tour Ronde (3793 m a.s.l.) normal route has been rendered unsustainable due to recurrent rockfalls during the summer months. This has necessitated the cessation of its utilisation. The Mont Blanc du Tacul (4248 m a.s.l.) normal route is also high on the list. Cross-parameter analysis reveals two primary categories of routes among the abandoned routes: those with a predominant progression on snow and ice (Dôme and Barre des Écrins, Mont Blanc, Pic de Neige Cordier, etc.) and those with a predominantly rocky profile located in permafrost-affected areas (Cosmiques ridge, Drus west face).

3.3.2 The most iconic routes for French mountain guides

The majority of guides (56.3 %) subscribe to the view that there are iconic and cultural routes that must be climbed with clients, and 75.5 % of the guides believe that climbing iconic routes constitutes a significant part of their role as a guide during the summer months. The Meije (3983 m a.s.l.) ridge is subject to 15 distinct processes. It is the route that has been most extensively impacted by a variety of geomorphological and glaciological processes. Furthermore, it is the most frequently traversed route by French mountain guides. Nevertheless, this route is also the most frequently selected option on the list of the most iconic routes that a guide should lead their clients up. This incongruity between the number of processes associated with climate change and the directive stipulating that guides must ascend specific routes underscores the significance of the cultural heritage (i.e. the history of the activity) of alpinism in shaping the routes selected by guides.

In the course of the present discussion, the various findings will be addressed from a perspective that is oriented towards the support of alpinists in their adaptation strategies. First, an explanation will be provided as to why modern alpinism with guides is less affected than “traditional” alpinism. This argument is pivotal in defending the practice against perspectives that portray it as a perilous undertaking. Furthermore, it is imperative in order to respond to the insurance logic of professionals. A meticulous, methodical and perspicacious approach to the practice will facilitate their discussions with, for instance, insurance companies in order to sustain their activity.

In the following section, an analysis of the various developments in routes and practices will be offered. The purpose of this analysis is to enable alpinists to project themselves into the future evolution of routes and anticipate issues that may arise in the years to come.

4.1 Different levels of change between the most frequented routes by French mountain guides and routes from Rébuffat's collection

For the routes that were the focus of the study in the Mont Blanc, Valais and Écrins massifs, it was found that one-third had undergone slight evolution (Level 1), one-third had undergone moderate evolution (Level 2) and one-quarter had undergone substantial evolution (Level 3). For the routes most frequently used by French mountain guides, the majority (58 %) were rated Level 1 during the interviews (Fig. 4).

Figure 4Different levels of change in percentage of the total number of routes of each study (most frequented routes by French mountain guides; Mourey et al., 2019b, 2022a; Arnaud et al., 2024).

It has been determined that the routes most frequently utilised by French mountain guides between 2017 and 2022 are less impacted by geomorphological and glaciological processes when compared to routes delineated in Rébuffat's guidebooks. This discrepancy can be attributed to the fact that the routes documented in Rébuffat's collections have been significantly impacted by the effects of climate change over the past three decades (Mourey et al., 2019b, 2022a; Arnaud et al., 2024). Conversely, over the preceding three decades, tour guides have had the opportunity to adapt to the evolution of the routes. As time passed, the decision was gradually made to select the less affected routes during the summer season. Consequently, the iconic routes of the 1980s, which were regarded by the community as being too hazardous, have been progressively forsaken.

Indeed, alpinists are constantly adapting their practices (Mourey et al., 2019b; Salim et al., 2019), leading to new ways of practising in terms of seasonality, progression techniques, ascent and even the appropriation of routes according to the logic of descent (Cailhol, 2021) in order to maintain an acceptable level of risk-taking (Cailhol, 2021). Beyond the adaptation, the perception of risk appears to evolve over time. The aforementioned assertions are accentuated by the qualitative interviews conducted with guides, which yielded comments such as “At last, the summer of 2023 was not as bad as 2022”. Furthermore, SNGM initiated a communication campaign in 2021, with the objective of reaffirming that adaptation constitutes the very foundation of their activity. This campaign formed part of the celebrations for the 200th anniversary of the Compagnie des Guides de Chamonix. The campaign concentrated on the guides' capacity for adaptation to change. When comparing the selection of less affected routes and the importance of adapting to climate change as the essence of the profession, it can be stated that guides have developed more than a “climate intelligence” in the sense of Bourdeau et al. (2014): they have developed a real “culture of adaptation” to the effects of climate change, thanks to homemade risk management strategies described by Girard (2024) and to their extreme mobility. This allows guides to take advantage of optimal conditions during the summer season. Alpinism is undergoing changes so as to take into account the risks related to emerging geomorphological and glaciological processes.

4.2 Different impacts depending on the massifs due to different ways of accessing alpinism routes

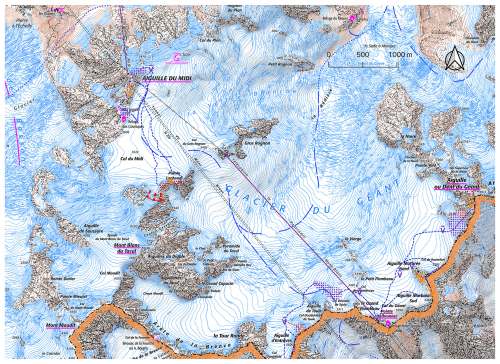

It has been demonstrated that the routes most frequently used by French mountain guides are less affected by the effects of climate change than most of the routes detailed in Les 100 plus belles courses. Routes in the Écrins and Vanoise massifs are affected by a higher number of processes on average than those in the Mont Blanc massif, which is located at a higher altitude (Fig. 5).

This discrepancy can be attributed to the observation that a significant proportion of the routes within the Mont Blanc massif originate from either the Aiguille du Midi cable car, situated at an elevation of 3842 m a.s.l., or the Skyway Monte Bianco cable car, located at 3466 m a.s.l. (Fig. 4). It is evident that the majority of these routes is situated in regions that have been less impacted by glacier retreat (Hoelzle et al., 2011; Beniston et al., 2018). This is due to the fact that these regions have undergone less development of debris cover (Scherler, 2018), less steepening of moraines (Ravanel and Lambiel, 2013; Ravanel et al., 2018) and an increase in rockfalls from recently deglaciated areas (Ravanel et al., 2018). In the event of the Mont Blanc massif being climbed from the valley floor, the number of processes affecting it would increase significantly.

Although the utilisation of ski lifts along the most popular routes, as employed by French mountain guides, may be perceived as mitigating the risks associated with exposure to various processes, it has the potential to exacerbate other concerns in two distinct ways. At the Aiguille du Midi (Chamonix), the number of places available for alpinists in the first cabins is limited, especially because a significant proportion of the tourists visiting the Aiguille du Midi also use these cabins. During the summer months, an increasing number of alpinists opt to utilise the lift to undertake ascents of 1 d routes. The results of semi-structured interviews indicated that guides and alpinists frequently have to take a cabin later in the day. According to interviews, guides stated that this delay exposes them to the warming of snow, already amplified by climate change (Mourey et al., 2022b). This phenomenon cannot be represented on our maps. In June 2023, a substantial series of snow slope falls occurred in the French Alps (data from the Peloton de Gendarmerie de Haute Montagne (PGHM)). An analysis of interventions carried out by the Système National d'Observation de la Sécurité en Montagne (SNOSM) and Chamonix PGHM revealed that 45.5 % of accidents related to snow slopes occurred on routes starting from the Aiguille du Midi or Skyway Monte Bianco. The aforementioned incidents all took place between 11:45 (European standard time) on the morning of the day in question and 20:20, which is considered to be late for snow routes. The increased accessibility to high mountains due to cable cars appears to have resulted in the trivialisation of certain principles, including timetables and more substantial recommendations to avoid risks induced by permafrost destabilisation. For instance, during the summer months, alpinists scale the Cosmiques Ridge on the Aiguille du Midi and “Traversée des Aiguilles Marbrées” (3535 m a.s.l.), often in the context of rockfalls. The ease with which iconic routes and sites can be accessed can result in cognitive biases in the selection of routes. The phenomenon of swiftness and proximity engendered by expeditious access instils a fallacy of security, with the potential to influence the decision to ascend. Through the integration of contingencies, including the technical evolution of routes due to geomorphological changes, a delayed start and the accelerated rise in temperature frequently observed at high altitudes in recent years, a novel form of risk-taking in alpinism is evident (Ravanel et al., 2023). It is also important to note that when mountain guides and alpinists adapt to climate change, they must collaborate with relevant stakeholders, including lift companies and politicians, to ensure continued access to high mountain areas in accordance with their personalised adaptation strategies.

Figure 5Map of the effects of climate change on the Glacier du Géant area (Mont Blanc massif, France), highlighting a very small number of processes that affect alpinism routes, still making this area a high place for alpinism in summer, especially for mountain guides (base map: IGN). See Fig. 1 for caption.

4.3 Exceptional geomorphological and glaciological processes in 2022 led to various adaptation in alpinism

The semi-directive interviews conducted revealed that the year 2022 posed significant challenges to the adaptation measures implemented by alpinists. It was demonstrated that, during the summer period, the impacts of climate change on the most frequently used routes necessitated, on average, two intervention or adaptation strategies for the 20 routes located above 3000 m a.s.l. that were studied. The most prevalent measure has been the discontinuation of commercial offerings by one or more guide companies during a period of the summer. Furthermore, official recommendations have been issued by mountain authorities and local decision-makers to avoid 30 % of these routes during periods of extreme heat, as indicated by press releases and official statements. These alterations can be attributed to glacial retreat, resulting in an increase in the slope angle of glaciers and the exposure of bare ice. Additionally, there has been a surge in rockfall frequency on four routes, an escalation in the occurrence of rockfall > 100 m3 on four routes and serac falls on one route. New challenges have arisen from the opening of new crevasses, as observed on two routes. Concurrently, novel variants (route modifications) have been implemented to ensure safety in 45 % of the most frequently traversed routes by French mountain guides. The geomorphological and glaciological changes described in this paper, which have been analysed using the methodology developed in this study, have the potential to exert a significant influence on alpinism during specific periods. Moreover, these changes may also have substantial economic consequences for those working in the mountain hut keeping and mountain guiding sectors.

4.4 Continuum in processes

In the observed itineraries, the processes appear to be operating in a cascading manner, characterised by distinct temporal phases. For instance, substantial rockfalls frequently precipitate additional phenomena within the affected area, including an escalation in rockfall frequency or the occurrence of debris flows.

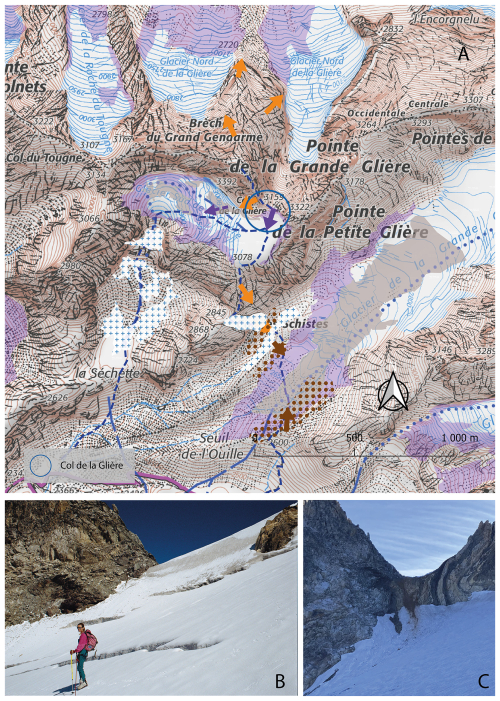

The retreat of glaciers and ice aprons has been demonstrated to trigger a succession of immediate or delayed processes with the potential to impact alpinism practice. These include an increase in rockfall frequency in recently deglaciated areas and an increase in rockfall frequency from moraines. Col de la Glière (3159 m a.s.l.) in Vanoise serves as a compelling exemplar of such a sequence of phenomena (Fig. 6): glacier retreat precipitated the gradual emergence of a steep rock slope (ca. 45°) overlaid by moraine (tills) across a span of approximately 50 m. This comparatively fine deposit, characterised by the presence of large boulders, introduces an additional level of complexity to the ascent, thereby enhancing the challenge faced by climbers. The installation of fixed ropes has been implemented with the objective of facilitating the process of crossing. However, it should be noted that these ropes are anchored to boulders, with the potential to dislodge. The risks associated with falling rocks, increased slope angles, the challenges and discomfort experienced during ascents and the uncertainty surrounding the reliability of equipment are consequences of climate change. It is evident that during the summer months of the years 2022 and 2023, the slope in question underwent a natural clearance process of the aforementioned deposits. Consequently, the formation of compact bedrock became evident. In the coming years, it is highly probable that the moraine along the west route to the col will be completely eliminated. It is anticipated that the introduction of a new, more or less equipped portion will serve to render the climb easier in this section of the route. It is evident that a single process (i.e. glacial retreat) gives rise to several other processes, which are conceptually considered as a continuum of the initial process. The cascading effects of these factors have been shown to have divergent consequences for alpinism, contingent on parameters such as the level of difficulty of the route and the typology of the alpinists who undertake this route. This inherent complexity renders the forecasting of future changes to the routes a highly challenging endeavour. The semi-structured interviews conducted revealed that the alpinists experienced difficulty in recalling the precise chronology of these processes. It is therefore evident that the ability to provide a comprehensive description of the dynamics in operation is instrumental in facilitating the provision of support to alpinists in the management of their routes across various massifs.

Figure 6(A) Map of the effects of climate change on the Pointe de la Grande Glière (3392 m a.s.l., Vanoise, France) normal route (base map: IGN). See Fig. 1 for caption. (B) Col de la Glière in September 1989 (photo: Bernard Vion); at this time, the col was still ice covered. (C) Col de la Glière in August 2023, free of ice for 20 years.

4.5 The abandonment of the highest altitudes in favour of mid-altitude routes, a solution that creates new problems

In consequence of geomorphological and glaciological processes occasioned by climate change in high mountains, and due to the fact that mid-altitude routes are to a lesser extent affected by these processes, climbing mid-altitude routes has the potential to serve as a means of sustaining economic activity during periods when the high mountains are regarded as too hazardous. The rock routes that have been studied, which reach altitudes below 3500 m a.s.l., appear to be comparatively less impacted than other routes.

However, the notion of preserving cultural practices, as well as the loss (or damage) of cultural practices, was frequently cited during the interviews as rationales for sustaining alpinism-related activities in the high mountains. Alpinists appear to demonstrate a strong commitment to their chosen field of practice, as well as to the notion of possessing the necessary flexibility and expertise to engage in climbing at elevated altitudes when conditions are conducive to doing so. In a similar manner, the movement of alpinists from the highest regions of the massifs during periods of heat waves, with the objective of minimising their risk-taking, has also given rise to tensions with other users of mid-altitude areas. These other users include, but are not limited to, mountain professionals such as mountain leaders, rock climbing instructors and farmers or hunters. These individuals have become accustomed to maintaining and utilising these areas and have done so with minimal interaction with other actors. The soothing effects of climbing at elevated altitudes, as described by the interviewed guides, are counterbalanced by the tensions experienced with other practitioners in the area. This phenomenon often results in high-mountain guides seeking alternative alpinism locations to continue their practice in more stable conditions.

Moreover, in high-mountain regions, there is a paucity of coexistence with non-human species. However, on the standard route of Mont Aiguille (2087 m a.s.l., Vercors massif, France), guides have reported an increase in herds of ibex grazing on the north face above the standard route during periods of heat. As demonstrated in extant research (e.g. Aublet, 2009), seasonal migrations of ibex at higher altitudes have been confirmed in the context of climate change. This process underscores the necessity for future modifications to existing practices, with a view to decreasing altitude. Such modifications will be required to ensure the preservation of species and human activities at these altitudes.

This study demonstrates that climate change is a tangible reality that is shaping the daily practice of French mountain guides. A detailed analysis of 216 routes has been undertaken, revealing that accelerated glacier retreat, permafrost degradation and increased rockfalls have altered the technical and safety conditions of alpinism routes. On average, the most popular routes are affected by seven geomorphological or glaciological processes, while the emblematic routes described by Rébuffat are affected by nine. This highlights the fact that some historic itineraries are now abandoned. In response to these changes, mountain guides have implemented a range of adaptations. It is noteworthy that certain routes, including the Goûter route on Mont Blanc and the Dôme de Neige des Écrins route, have been subject to seasonal suspension or abandonment due to their non-compliance with acceptable safety standards at specific times during the year. In other areas, new variants have been established to bypass unstable sections, and some ascents are more commonly scheduled for spring or autumn in order to avoid the warmer summer periods. The evolution of these practices demonstrates the emergence of an authentic culture of adaptation, where professionals are required to maintain a constant balance between professional responsibility, client expectations and environmental realities. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the process of adaptation is not without its own particular tensions. The endurance of high-altitude alpinism, which is profoundly embedded within the profession's symbolic heritage, occasionally finds itself in discord with the risks engendered by climate change. Conversely, the shift towards mid-altitude rock routes, which are less exposed to cryospheric processes, creates new forms of tension with other land users, as well as with wildlife. This dual movement, involving the abandonment of high-mountain areas and the reinvention of practices at lower altitudes, reveals a cultural negotiation imposed on the guiding profession by climate change.

In conclusion, it is evident that climate change is having a profound impact on both the Alpine landscapes and the culture of alpinism. French mountain guides are adapting to these changes through their mobility, creativity and experience. It is evident that there is an ongoing endeavour to preserve the symbolic value of high mountains. Concurrently, novel guiding practices are being devised to ensure safety and the continuity of the profession. In order to sustain this fragile balance in the years to come, it will be essential to support these strategies through training, communication and coordination with other stakeholders in the Alpine region.

Data can be accessed by contacting the corresponding author (xavier.cailhol@univ-smb.fr).

XC, JM and LR designed the study. XC mapped the geomorphological and glaciological processes. XC, JM and LR analysed and discussed them. XC wrote the article. LR and JM improved the article.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This study is part of the EU Alcotra PrévRisk-CC project. We thank all the guides, refuge keepers and alpinists who contributed to the work.

This paper was edited by Martin Hoelzle and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Arnaud, M., Mourey, J., Bourdeau, P., Bonet, R., and Ravanel, L.: Impacts of climate change on mountaineering routes in the Écrins massif (Western Alps, France). Analysis based on a corpus of 70 itineraries from the topoguide “Les 100 plus belles courses et randonnées” (1974), Journal of Alpine Research, https://doi.org/10.4000/12a6u 2024.

Aublet, J.-F., Festa-Bianchet, M., Bergero, D., and Bassano, B.: Temperature constraints on foraging behaviour of male Alpine ibex (Capra ibex) in summer, Oecologia, 159, 237–247, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-008-1198-4, 2009.

Beniston, M., Farinotti, D., Stoffel, M., Andreassen, L. M., Coppola, E., Eckert, N., Fantini, A., Giacona, F., Hauck, C., Huss, M., Huwald, H., Lehning, M., López-Moreno, J.-I., Magnusson, J., Marty, C., Morán-Tejéda, E., Morin, S., Naaim, M., Provenzale, A., Rabatel, A., Six, D., Stötter, J., Strasser, U., Terzago, S., and Vincent, C.: The European mountain cryosphere: a review of its current state, trends, and future challenges, The Cryosphere, 12, 759–794, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-12-759-2018, 2018.

Berthier, E., Vincent, C., Magnússon, E., Gunnlaugsson, Á. Þ., Pitte, P., Le Meur, E., Masiokas, M., Ruiz, L., Pálsson, F., Belart, J. M. C., and Wagnon, P.: Glacier topography and elevation changes derived from Pléiades sub-meter stereo images, The Cryosphere, 8, 2275–2291, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-8-2275-2014, 2014.

Bourdeau, P.: Effets du changement climatique sur l’alpinisme et nouvelles interactions avec la gestion des espaces protégés en haute-montagne, https://www.ecrins-parcnational.fr/sites/ecrins-parcnational.com/files/article/23303/2023-09-stage-mathis-arnaud-m2-epgm-impact-changement (last access: 15 December 2025), 2014.

Cailhol, X.: De l'ascension à la descension, deux manières d'aborder le paysage?, paysage, https://doi.org/10.4000/paysage.23490, 2021.

Cailhol, X., Ravanel, L., and Mourey, J.: Impacts of climate changes on alpinism – A review, Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment, 03091333251380035, https://doi.org/10.1177/03091333251380035, 2025.

Colgan, W., Rajaram, H., Abdalati, W., McCutchan, C., Mottram, R., Moussavi, M. S., and Grigsby, S.: Glacier crevasses: Observations, models, and mass balance implications, Reviews of Geophysics, 54, 119–161, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015RG000504, 2016.

Collins, 2008, Collins, D. N.: Climatic warming, glacier recession and runoff from Alpine basins after the Little Ice Age maximum, Ann. Glaciol., 48, 119–124, https://doi.org/10.3189/172756408784700761, 2008.

de Bellefon, R.: L’invention du terrain de jeu de l’alpinisme : d’une montagne l’autre, Ethnologie Française, 29, 66–78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40990102 (last access:15 December 2025), 1999.

Deline, P., Gardent, M., Magnin, F., and Ravanel, L.: The morphodynamics of the mont blanc massif in a changing cryosphere: a comprehensive review, Geografiska Annaler: Series A, Physical Geography, 94, 265–283, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0459.2012.00467.x, 2012.

Deline, P., Gruber, S., Delaloye, R., Fischer, L., Geertsema, M., Giardino, M., Hasler, A., Kirkbride, M., Krautblatter, M., Magnin, F., McColl, S., Ravanel, L., and Schoeneich, P.: Ice loss and slope stability in high-mountain regions, in: snow and ice-related hazards, risks, and disasters, Elsevier, 521–561, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-394849-6.00015-9, 2015.

Dobhal, D. P.: Surface morphology, elevation changes and Terminus retreat of Dokriani Glacier, Garhwal Himalaya: implication for climate change, Himalayan Geology, 31, 71–78, 2010.

Draebing, D. and Eichel, J.: Divergence, convergence, and path dependency of paraglacial adjustment of alpine lateral moraine slopes, Land Degrad. Dev., 29, 1979–1990, https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.2983, 2018.

Eichel, J., Draebing, D., and Meyer, N.: From active to stable: Paraglacial transition of Alpine lateral moraine slopes, Land Degrad. Dev., 29, 4158–4172, https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.3140, 2018.

Faillettaz, J., Funk, M., and Vincent, C.: Avalanching glacier instabilities: Review on processes and early warning perspectives, Reviews of Geophysics, 53, 203–224, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014RG000466, 2015.

Fischer, L., Kääb, A., Huggel, C., and Noetzli, J.: Geology, glacier retreat and permafrost degradation as controlling factors of slope instabilities in a high-mountain rock wall: the Monte Rosa east face, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 6, 761–772, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-6-761-2006, 2006.

Fischer, M., Huss, M., Barboux, C., and Hoelzle, M.: The new Swiss glacier inventory SGI2010: relevance of using high-resolution source data in areas dominated by very small glaciers, Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 46, 933–945, https://doi.org/10.1657/1938-4246-46.4.933, 2014.

Gardent, M., Rabatel, A., Dedieu, J.-P., and Deline, P.: Multitemporal glacier inventory of the French Alps from the late 1960s to the late 2000s, Global and Planetary Change, 120, 24–37, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2014.05.004, 2014.

Girard, A.: De la perception des risques à la construction de la sécurité dans le métier de guide de haute montagne : prendre et faire prendre des risques en sécurité., thesis, Université Grenoble Alpes, https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.31089.80485, 2024.

Glacier Monitoring of Switzerland (GLAMOS): Swiss Glacier Length Change (release 2020), Glacier Monitoring Switzerland [data set], https://doi.org/10.18750/LENGTHCHANGE.2020.R2020, 2020.

Gomez, B. and Small, R.: Medial moraines of the Haut Glacier d'Arolla, Valais, Switzerland: debris supply and implications for moraine formation, J. Glaciol., 31, 303–307, https://doi.org/10.3189/S0022143000006638, 1985.

Hanly, K. and McDowell, G.: The evolution of “riskscapes”: 100 years of climate change and mountaineering activity in the Lake Louise area of the Canadian Rockies, Climatic Change, 177, 49, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-024-03698-2, 2024.

Hartmeyer, I., Delleske, R., Keuschnig, M., Krautblatter, M., Lang, A., and Otto, J.-C.: Current glacier recession causes significant rockfall increase: The immediate paraglacial response of deglaciating cirque walls, https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-8-729-2020, 2020.

Hoelzle, M., Darms, G., Lüthi, M. P., and Suter, S.: Evidence of accelerated englacial warming in the Monte Rosa area, Switzerland/Italy, The Cryosphere, 5, 231–243, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-5-231-2011, 2011.

Huss, M.: Extrapolating glacier mass balance to the mountain-range scale: the European Alps 1900–2100, The Cryosphere, 6, 713–727, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-6-713-2012, 2012.

Huss, M., Bookhagen, B., Huggel, C., Jacobsen, D., Bradley, R. S., Clague, J. J., Vuille, M., Buytaert, W., Cayan, D. R., Greenwood, G., Mark, B. G., Milner, A. M., Weingartner, R., and Winder, M.: Toward mountains without permanent snow and ice, Earth's Future, 5, 418–435, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016EF000514, 2017.

Huss, M., Bauder, A., Hodel, E., and Linsbauer, A.: Swiss Glacier Bulletin 2024: Annual report #145 on glacier observation in Switzerland, GLAMOS - Glacier Monitoring Switzerland, https://doi.org/10.18752/GLBULLETIN_2024, 2025.

Intergovernmental panel on climate change (IPCC): the ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate: special report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change, 1st Edn., Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157964, 2022.

Lambiel, C., Maillard, B., Kummert, M., and Reynard, E.: Geomorphology of the Hérens valley (Swiss Alps), Journal of Maps, 12, 160–172, https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2014.999135, 2016.

Laurencelle, L.: La représentativité d’un échantillon et son test par le Khi-deux; Testing the representativeness of a sample, TQMP, 8, 173–181, https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.08.3.p173, 2012.

Legay, A., Magnin, F., and Ravanel, L.: Rock temperature prior to failure: Analysis of 209 rockfall events in the Mont-Blanc massif (Western European Alps), Permafrost and Periglacial, 32, 520–536, https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp.2110, 2021.

Magnin, F., Ravanel, L., Bodin, X., Deline, P., Malet, E., Krysiecki, J., and Schoeneich, P.: Main results of permafrost monitoring in the French Alps through the PermaFrance network over the period 2010–2022, Permafrost and Periglacial, 35, 3–23, https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp.2209, 2024.

McColl, S. T.: Paraglacial rock-slope stability, Geomorphology, 153–154, 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2012.02.015, 2012.

Mercier, D.: Le “géosystème paraglaciaire” face aux changements climatiques [“Paraglacial landsystem” facing climate change], Bulletin de l'Association de géographes français, 85, 131–140, 2008.

Mourey, J., Ravanel, L., Lambiel, C., Strecker, J., and Piccardi, M.: Access routes to high mountain huts facing climate-induced environmental changes and adaptive strategies in the Western Alps since the 1990s, Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography, 73, 215–228, https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2019.1689163, 2019a.

Mourey, J., Marcuzzi, M., Ravanel, L., and Pallandre, F.: Effects of climate change on high Alpine mountain environments: Evolution of mountaineering routes in the Mont Blanc massif (Western Alps) over half a century, Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 51, 176–189, https://doi.org/10.1080/15230430.2019.1612216, 2019b.

Mourey, J., Perrin-Malterre, C., and Ravanel, L.: Strategies used by French alpine guides to adapt to the effects of climate change, Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 29, 100278, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2020.100278, 2020.

Mourey, J., Ravanel, L., and Lambiel, C.: Climate change related processes affecting mountaineering itineraries, mapping and application to the Valais Alps (Switzerland), Geografiska Annaler: Series A, Physical Geography, 104, 109–126, https://doi.org/10.1080/04353676.2022.2064651, 2022a.

Mourey, J., Lacroix, P., Duvillard, P.-A., Marsy, G., Marcer, M., Malet, E., and Ravanel, L.: Multi-method monitoring of rockfall activity along the classic route up Mont Blanc (4809 m a.s.l.) to encourage adaptation by mountaineers, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 22, 445–460, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-22-445-2022, 2022b.

Miller, J. D., Immerzeel, W. W., and Rees, G.: Climate Change Impacts on Glacier Hydrology and River Discharge in the Hindu Kush–Himalayas: A Synthesis of the Scientific Basis, Mountain Research and Development, 32, 461–467, https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-12-00027.1, 2012.

Purdie, H., Gomez, C., and Espiner, S.: Glacier recession and the changing rockfall hazard: Implications for glacier tourism, N Z Geog, 71, 189–202, https://doi.org/10.1111/nzg.12091, 2015.

Ravanel, L., Lacroix, E., Le Meur, E., Batoux, P., and Malet, E.: Multiparameter monitoring of crevasses on an Alpine glacier to understand formation and evolution of snow bridges, Cold Regions Science and Technology, 203, 103643, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2022.103643, 2022.

Noetzli, J., Isaksen, K., Barnett, J., Christiansen, H. H., Delaloye, R., Etzelmüller, B., Farinotti, D., Gallemann, T., Guglielmin, M., Hauck, C., Hilbich, C., Hoelzle, M., Lambiel, C., Magnin, F., Oliva, M., Paro, L., Pogliotti, P., Riedl, C., Schoeneich, P., Valt, M., Vieli, A., and Phillips, M.: Enhanced warming of European mountain permafrost in the early 21st century, Nat. Commun., 15, 10508, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-54831-9, 2024.

Pohl, B., Joly, D., Pergaud, J., Buoncristiani, J.-F., Soare, P., and Berger, A.: Huge decrease of frost frequency in the Mont-Blanc Massif under climate change, Sci. Rep., 9, 4919, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41398-5, 2019.

Purdie, H. and Kerr, T.: Aoraki Mount Cook: Environmental change on an iconic mountaineering route, Mountain Research and Development, 38, 364, https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-18-00042.1, 2018.

Rabatel, A., Letréguilly, A., Dedieu, J.-P., and Eckert, N.: Changes in glacier equilibrium-line altitude in the western Alps from 1984 to 2010: evaluation by remote sensing and modeling of the morpho-topographic and climate controls, The Cryosphere, 7, 1455–1471, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-7-1455-2013, 2013.

Ravanel, L. and Lambiel, C.: Evolution récente de la moraine des Gentianes (2894 m, Valais, Suisse): un cas de réajustement paraglaciaire?, Environnements périglaciaires, 18, 2013.

Ravanel, L., Deline, P., Lambiel, C., and Vincent, C.: Instability of a high alpine rock ridge: the lower Cosmiques ridge, Mont-Blanc massif, france, Geografiska Annaler: Series A, Physical Geography, 95, 51–66, https://doi.org/10.1111/geoa.12000, 2013.

Ravanel, L., Magnin, F., and Deline, P.: Impacts of the 2003 and 2015 summer heatwaves on permafrost-affected rock-walls in the Mont-Blanc massif, Science of The Total Environment, 609, 132–143, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.07.055, 2017.

Ravanel, L., Duvillard, P., Jaboyedoff, M., and Lambiel, C.: Recent evolution of an ice-cored moraine at the Gentianes Pass, Valais Alps, S witzerland, Land Degrad. Dev., 29, 3693–3708, https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.3088, 2018.

Ravanel, L., Lacroix, E., Le Meur, E., Batoux, P., and Malet, E.: Multiparameter monitoring of crevasses on an Alpine glacier to understand formation and evolution of snow bridges, Cold Regions Science and Technology, 203, 103643, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coldregions.2022.103643, 2022.

Ravanel, L., Mourey, J., Tamian, L., Ibanez, S., Hantz, D., Lacroix, P., and Duvillard, P.-A.: Ascension du Mont-Blanc (4808 m): quels risques prend-on dans le Grand Couloir du Goûter et dans la face nord du Mont-Blanc du Tacul?, Journal of Alpine Research, https://doi.org/10.4000/rga.11728, 2023.

Rébuffat, G: Le massif du Mont-Blanc – Les 100 plus belles courses, ISBN 9782207220108, 1973.

Rébuffat, G: Le massif des Écrins – Les 100 plus belles courses et randonnées, ISBN 978-2207252321, 1974.

Vaucher, M.: Les Alpes Valaisannes – Les 100 plus belles courses, edited by: Rébuffat, G, ISBN 9782207225912, 1979.

Ritter, F., Fiebig, M., and Muhar, A.: Impacts of global warming on mountaineering: a classification of phenomena affecting the Alpine trail network, Mountain Research and Development, 32, 4–15, https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-11-00036.1, 2012.

Salim, E., Mourey, J., Ravanel, L., Picco, P., and Gauchon, C.: Les guides de haute montagne face aux effets du changement climatique. Quelles perceptions et stratégies d'adaptation au pied du Mont-Blanc?, rga, https://doi.org/10.4000/rga.5842, 2019.

Scherler, D., Wulf, H., and Gorelick, N.: Global assessment of supraglacial debris-cover extents, Geophysical Research Letters, 45, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL080158, 2018.

Scherrer, S. C., Gubler, S., Wehrli, K., Fischer, A. M., and Kotlarski, S.: The Swiss Alpine zero degree line: methods, past evolution and sensitivities, Intl. Journal of Climatology, 41, 6785–6804, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.7228, 2021.

Schoeneich, P.: Comparaison des systèmes de légende Français, Allemand et Suisse – principes de la légende IGUL, 9, 15–24, 1993.

Scherler, D., Wulf, H., and Gorelick, N.: Global Assessment of Supraglacial Debris‐Cover Extents, Geophysical Research Letters, 45, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL080158, 2018.

The GlaMBIE Team, Zemp, M., Jakob, L., Dussaillant, I., Nussbaumer, S. U., Gourmelen, N., Dubber, S., A, G., Abdullahi, S., Andreassen, L. M., Berthier, E., Bhattacharya, A., Blazquez, A., Boehm Vock, L. F., Bolch, T., Box, J., Braun, M. H., Brun, F., Cicero, E., Colgan, W., Eckert, N., Farinotti, D., Florentine, C., Floricioiu, D., Gardner, A., Harig, C., Hassan, J., Hugonnet, R., Huss, M., Jóhannesson, T., Liang, C.-C. A., Ke, C.-Q., Khan, S. A., King, O., Kneib, M., Krieger, L., Maussion, F., Mattea, E., McNabb, R., Menounos, B., Miles, E., Moholdt, G., Nilsson, J., Pálsson, F., Pfeffer, J., Piermattei, L., Plummer, S., Richter, A., Sasgen, I., Schuster, L., Seehaus, T., Shen, X., Sommer, C., Sutterley, T., Treichler, D., Velicogna, I., Wouters, B., Zekollari, H., and Zheng, W.: Community estimate of global glacier mass changes from 2000 to 2023, Nature, 639, 382–388, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08545-z, 2025.

Vincent, C., Fischer, A., Mayer, C., Bauder, A., Galos, S. P., Funk, M., Thibert, E., Six, D., Braun, L., and Huss, M.: Common climatic signal from glaciers in the European Alps over the last 50 years, Geophysical Research Letters, 44, 1376–1383, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL072094, 2017.

Vincent, C., Harter, M., Gilbert, A., Berthier, E., and Six, D.: Future fluctuations of Mer de Glace, French Alps, assessed using a parameterized model calibrated with past thickness changes, Ann. Glaciol., 55, 15–24, https://doi.org/10.3189/2014AoG66A050, 2014.

Vincent, C., Thibert, E., Harter, M., Soruco, A., and Gilbert, A.: Volume and frequency of ice avalanches from Taconnaz hanging glacier, French Alps, Ann. Glaciol., 56, 17–25, https://doi.org/10.3189/2015AoG70A017, 2015.

World Glacier Monitoring Service (WGMS): Fluctuations of glaciers database, https://doi.org/10.5904/WGMS-FOG-2015-11, 2015.