the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Insurrections in Iran: an off-site ethnography

Chowra Makaremi

- Article

(6012 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Like every night in the autumn of 2022, like tens of millions of other Iranians around the world, I stretch the hours between sleep and wakefulness by scrolling through photos and videos on my phone. I would like to have a virtual briefcase organized into carefully labeled folders so that I can store and classify each image and then easily find it again. But I do not have the time; there are just too many of them. They arrive just in time, and it seems impossible to consider them one by one. I jump from one medium to another: Telegram feeds, Twitter, Instagram, countless new groups I have been added to on WhatsApp and text messages from my dad sending me links, asking “Did you see that?” Then, when I go back on Telegram, there are dozens more new images.

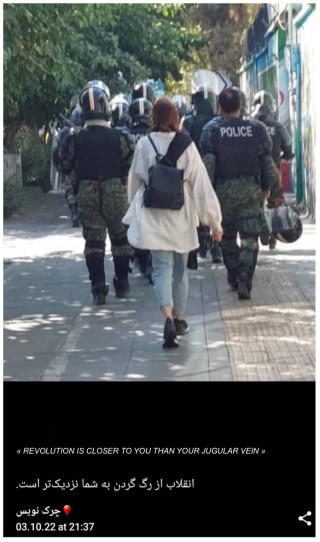

One of them became the symbol of the Woman, Life, Freedom uprisings for me. Taken in October 2022 in a street in Tehran, it shows a young girl walking behind a police brigade, her hair unveiled and pulled back in a loose ponytail. Some images capture moments of revolt, such as the photo that became a symbol of the 2019 uprisings in Lebanon, showing a young woman insurgent kicking a militiaman in the street. Here, on the contrary, the protester, the demonstrator, is deliberately playing with the camera. She is walking in step with the police, without them knowing, in order to produce this image. Its circulation is another way of occupying public space at a minor scale. As she mimicks the anti-riot police, her clownish gesture turns the threat upside down. The danger hanging over the forces of law and order is a woman without her veil. The caption reads, “Revolution is closer to you than your jugular vein.”

The jugular vein, the vital vein of the neck, is the physiological locus of anger in Persian: to express outrage, a person is said to have a swollen jugular vein. It is also where intimacy is located: to be closer to someone than their jugular vein means extreme closeness. We find this expression in a beautiful verse of the Qur'an, where it defines God's relationship to His creature: “We have created Man, and We know what his soul whispers to him. We are closer to him than his jugular vein” (The Qur'an, 50:16). Carried by hundreds of thousands of swollen jugular veins, reminding us of the power of collective emotions in the making of political events, the revolution is closer to power than the vein in its neck, which has already been struck (Fig. 1).

Figure 1“Revolution is closer to you than your jugular vein”, Telegram channel Cherk Nevis, 3 October 2022 (anonymous, 2023).

We watch photos and videos circulate, and we get emotional. From a distance, the events take the form of a collection of scenes that scroll past and sometimes repeat themselves on our screens; And yet they impose their own rhythms and emotions upon us. What can we know of an uprising through these images, voices and fragments of struggle? They ricochet off the surface of a social world that remains beyond our reach. But they acquire a different depth and density when they resonate with sequences from Iran's post-revolutionary history, other uprisings and struggles, other forms of violence, and failed attempts at change. I know this long-term history of power and resistance intimately from my family history, and I also know it because I study it as an anthropologist. For the past 10 years, I have been scrutinizing the archival traces, carrying the memories of an alternative historical narrative in Iran – counter-memories that were not allowed in the public space. Since September 2022, I have relied on the methods and knowledge of post-revolution Iran, acquired over the long term and through an “off-site” practice of ethnography, in order to observe at a distance the Woman, Life, Freedom uprisings. Before pointing out some of the main findings, I would like to share information about these events; let me start with a methodological note on the relevance, the limits and the opportunities of empirical observation at a distance.

Of course, as qualitative researchers we want to do investigations on-site. But at the end of the day, the question is about what should guide research agendas: data availability or the need to clarify grey zones of knowledge? As long as access to the field is what legitimatizes and delineates empirical knowledge, even the most impartial research remains dependent on power, particularly the topography of its impunity. But how can we produce empirical knowledge without field investigation? Through the “Off-Site” project,1 we looked for solutions to this methodological and epistemic question by re-examining, through our practice, the notion of “boundary” itself, in the age of global circulation and the Internet. Boundaries of knowledge, boundaries in repressive societies, and boundaries of political belongings and participation defined by authoritarian regimes are to be reconsidered in the light of (1) global mobility and how it affects the relation between locked insides and multiple outsides, (2) the circulation and availability of data through the Internet and social media, and (3) the production of global norms and practices of resistance (specifically, but not only, in the field of the law). These contexts and factors offer new opportunities for producing empirical knowledge off-site.

Taking up this challenge is a politics of knowledge that is guided by the following question: “how can we lead an empirical investigation without being present in the field?”, rather than “is it possible and scientifically acceptable to do empirical investigation without being present in the field?” By shifting the question, what we do as researchers is to push and challenge the boundaries of the scientific regime of truth, of how empirical knowledge is constructed. We challenge these methodological boundaries because, strategically, this is where we can make a move and loosen the knot in the relation between power and knowledge. We cannot change the political order; we cannot escape surveillance and repression in the field: in short, we cannot change the rules of the political game. But we can transform the rule of the scientific game in order to create conditions which allow for the continuity of knowledge production in contexts of political violence and silencing.

These methodological choices may become radical. This was the case as the presence of anthropologists in post-invasion Iraq was reframed in the “human terrain system”. This US military program trained and used “embedded ethnographers” for “mediation” and intelligence purposes among the population in Iraq and Afghanistan (Forte, 2011). Although particularly explicit in the way it sets out the asymmetrical symbiosis between ethnographic fieldwork, academic career and military uses of knowledge produced within the framework of an occupying power, this experience is not so much a shocking anomaly, as it is a particularly institutionalized continuation of a pattern that goes back to the origins of disciplines. Just think of the British colonial commission for Edward Evans-Pritchard's study of The Nuer in Sudan (Evans-Pritchard, 1940) or the Pentagon's commission for Ruth Benedict's study of the “Japanese spirit” during the Second World War, which led to the ethnographic classic The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture (Benedict, 2005). In the years following the US invasion of Iraq, in reaction to similar efforts to encapsulate the production of knowledge, a collaborative research study coordinated by Antonius Robben produced an ethnography of Iraq “at a distance” (Robben, 2010). The idea was that an off-site ethnography of occupied Iraq would be less biased than on-site fieldwork in the conditions of the “human terrain system”. The project offered the opportunity to conduct a methodological experiment, questioning the frontiers of ethnography. It compared second-hand data and ethnographic interviews with exiles, with the authors' previous experiences on other sites of war and counter-insurgency. The authors analyzed the effects of war on the Iraqi society in comparison with modalities of government elsewhere: in the Israeli occupied territories, Khmer Rouge's Cambodia, Northern Ireland, and the Argentinian dictatorship. Comparative ethnography has focused on “processes of change”, bearing in mind that “similar processes produce different meanings, discourses and practices” in different contexts (Robben, 2010:10). At the heart of this methodological essay is what its authors call the “ethnographic imagination” – an interpretive gamble based, on the one hand, on an effort to objectify the conditions of remote collection and the choice of material and, on the other, on the long-term practice of survey fields mobilized as points of comparison and the precise analysis of these analogies. Observations, interviews and presence in the field do not sum up the ethnographic method; it also engages a “sensibility” (Jourde, 2013). In this sense, the efforts made to design ethnographic observation at a distance, however impure they may seem in regards to the method, stem from a definition of knowledge as an attempt to grasp a little more of what remains off-field – out of range from concrete observation but also from our frameworks of interpretation and understanding.

Drawing on these experiments, I have been studying the long Iranian Revolution (from 1979 to 1989) at a distance. I pay attention to “counter-archives” by combining ethnographic interviews with oral history in the diasporas, archival ethnography, and digital ethnography and by looking at a large body of documentation produced through human rights initiatives for truth and justice. Over time, regimes of (in)visibility and visual sources became an important part of this material, in conversation with contemporary reflections on our modes of documenting violence and establishing facts (Weizman, 2014). Using online and open-source opportunities to collect material at a distance is not new in itself, although empirical social science has been – rightly – reluctant to take this turn, when other places of knowledge and certification (like the prosecutor's office of the International Criminal Court) have long engaged with it. What is more specific in off-site ethnography is the way we look at this material. I am considering it to be “archival traces”, i.e., documentation collected through the activity of a group of person, which needs contextualization and is inherently incomplete and informed by practice. And I am reading these archival fragments or streams through micro-historical methods developed by feminist historians working on issues such as slavery (Fuentes, 2016) and colonial violence (Stoler, 2010). These creative methods of making minimal archives “speak”, which pay particular attention to the question of affects and images, are not new in themselves. But what is specific to this project is mobilizing them to analyze testimonies accessible thanks to new technologies, and advancing a counter-investigation: what I call the “counter-archives” of violence. This project also involves reflecting on the ethical and methodological issues that arise when using these new technologies to collect this fragmented and scattered material, as well as working in the field of digital humanities (data modeling and metadata production) to classify and make this archival material accessible in a searchable database.

This empirical research in historical anthropology on the genealogies of state violence, nation-state formation and memory politics in post-revolution Iran (Makaremi, 2014, 2018, 2019; Darabi and Makaremi, 2019; Kunth and Makaremi, 2019) has informed, both methodologically and analytically, my observation at a distance of the Woman, Life, Freedom uprisings in Iran and the revolutionary turn they initiate in Iranian society. It gave flesh and depths to the thin digital material I explored in 2022 and 2023 (Makaremi, 2023b, a). This material combined online ethnographic interviews, digital ethnography on social networks and participant observation in “spaces” of discussion (Twitter, Clubhouse) where a variety of profiles from within and outside the country discussed precise, technical subjects (such as how to organize a white march or apply a tourniquet) or very general subjects such as which political project to support after the Islamic Republic of Iran. I also took part as a translator in truth and justice seeking initiatives or asylum files, which nurtured my analyses but which I could not detail more because of obvious ethical and security reasons.

Like in my previous work on the 1979 revolution, a key point here was to read this huge production of images and narratives as archives, or rather micro-archives, and to hold together the symbolic dimension, the imaginaries and cosmogonies, the political emotions and affects, and the material conditions of production and circulation online and on-site. Of course there are several research biases. The conditions are not optimum, and this is why reflexivity is crucial, in order to objectify the subjective conditions of production of knowledge. This is also what guided the choice of writing my analyses in the form of a chronicle in the first person.

Throughout the last year, I was riveted by the events unfolding in Iran through the screens: without abandoning this paradoxical distance, what I want to do in what follows is to give this spontaneous revolt a depth that enables one to identify its multiple geneses as well as to grasp the irreversible shift it represents, whatever the future may hold. I would like to do so by reflecting on memory, identity and subjectivation through three images.

A common image of the Woman, Life, Freedom movement that started in September 2022 in Iran portrays women taking off their veils and burning them (Fig. 2). In France, newspapers have celebrated the “waking-up” of Iranian women, as if taking off one's veil was an intuitive gesture of political awakening and liberation. This interpretation is obviously flawed. Iranian women have been awake for a long time; feminist movements have been the most powerful part of Iranian civil society since the mid-2000s. The dividing line in these feminist movements does not lie between veiled and non-veiled women. It is between those who agree with mandatory requirements and institutionalized segregation and those who do not.

Figure 2Demonstrator dancing and throwing her veil in the fire, Iran, September 2022 (credit: anonymous).

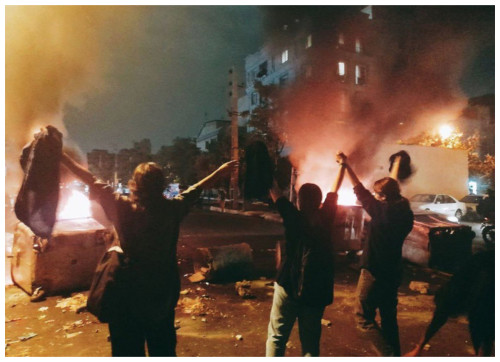

Taking off the veil started as a spontaneous collective action expressing outrage at the funerals of Jîna Mahsa Amini, which turned into a radical anti-regime demonstration in Saqqez on 17 September 2022. This practice reminds us of the importance of collective emotions in theories of action: feminist theories offer critical insights for understanding these revolts beyond the demand for gender equality. Specifically, historian Nicole Loraux and philosophers Judith Butler and Athena Athanasiou have pointed out the political potential of grieve and rage when these emotions reconfigure at a collective level and become forces of mobilization (Loraux, 2002; Butler, 2004; Athanasiou, 2017). Bereavement is not always a time for withdrawing into the private sphere. As recent uprisings have shown, triggered by the death of Mohamed Bouazizi in Tunisia in 2011, George Floyd in the United States in 2020, or Jîna Mahsa Amini in Iran in 2022, mourning is also a shared, radical and ritualized expression of loss that frames emotions and enables their reconfiguration into forces that literally move people into challenging political values and order (Fig. 3).

But taking off the veil is more than spontaneous; it is also very precise. It is a political act that indicates, with the greatest economy of means, that one goes up to the battlements to defy the established order frontally and in public. When women burn their veils and men applaud them, it is not so much that men support women, but that they make their revolt their own: women also act for the men, who have no veils to burn. The gesture of taking off the veil is strategic: it announces a radical shift and gives its exact coordinates.

Taking off the veil disarticulates the pact between society and state that has held since the 1979 revolution. It does so in four ways. First, it revives a posture with a complicated history in Iranian politics: that of antagonism, frontal opposition or “agonistic” position (Athanasiou, 2017). Second, this frontal opposition is assumed with joy and creativity: on the street, there is not only rage but also elation. Crucially, these feelings imply, and perform, an absence of fear. Third, this gesture produces a “we.” Women take off their veils, and people around them honk, applaud and shout that they are “women of honor” (bâ sharaf). The sounds spread their gesture in a collective re-appropriation. Finally – and the essential point that makes this gesture such a challenge – taking off the veil “crosses a red line”.

Over the past 30 years, Iranian citizenship has been shaped by a dialectic of bypassing and respecting the red lines. Red lines (khate ghermez) are not to be discussed; there are things not to be said or done if one does not want serious problems. These red lines map out the public space, which can widen or shrink. They are not inscribed on a map or listed anywhere at all: they are part of an obvious, implicit social knowledge, internalized by Iranians. Learning and constantly updating the map of these red lines is an early form of socialization. While some red lines are shifting or negotiable, others are immutable: they are the foundation on which the Iranian discourse of power has been built. The “Supreme Leader” (the function and the person) is one of those immutable red lines, as is the compulsory veil (Figs. 4 and 5). Over the decades, public space has been drawn and redrawn in shifting arrays of lines and borders. The process has redefined the relations between state and society, authority and the methods of social control.

Figure 4Women sitting unveiled in front of a riot police patrol, Tehran, September 2022 (credit: anonymous).

Figure 5Demonstrator throwing Molotov cocktails on a billboard portrait of the supreme leader Ali Khamenei, on a highway airlift, Iran, November 2022 (credit: anonymous).

These internalized red lines have produced multiple forms of individual, collective and institutional self-censorship – in academic or cultural fields for certain, as well as in political activism and the world of NGOs. Iranian civil society and public life from the 1990s onwards have accepted the realities of censorship and played with those realities to strategically open up avenues of expression or change. Such an approach implied working from within and respecting the red lines to avoid jeopardizing a fragile but dynamic economy of resistance. With every step, actors in civil society and public life accessed the possibilities of continuing to act (work, speak, move) and asked, “Will this action/subject create a problem that will stop me, or will it allow me to continue?”

The consequences of this strategy were twofold. On the one hand, respecting the red lines was resistance of a different kind. It disabled the effects of power by deserting its front lines, in order to foster change from within the legal and political system whose premises were (at least strategically) accepted. While state apparatus and discourse are imposed by the use of force, there is no one to confront them: people move on in search of possible margins of change in everyday life. But on the other hand, through this practice, the limits of what can and cannot be discussed end up being internalized. Moreover, if no one tests limits, they do not move: they do not shift and they do not tremble. Those limits become calcified as a set of forbidden topics never reported on. The red lines have led Iranian society to progressively metabolize the boundaries sedimented through state coercion and ideology. In this process, what were initially experienced as sensitive subjects or dangerous acts became morally, socially and emotionally devalued subjects with which people did not want to be associated with and with which they would not engage. Thus, pragmatic acceptation of these boundaries led to their internalization; civil society became the guardian of the state's red lines. The Islamic Republic of Iran, in short, built an extremely repressive power by manufacturing acceptance. The distinction made by Hannah Arendt between obedience (as a forced submission under constraint) and adherence (based on shared values, affects and persuasion) (Arendt, 1951) is of importance here, and it seems that there has been a constant shift from one term to the other in Iranian society.

Interestingly, the red lines were a well-known concept with many implications but have never been studied as a political and social process. I came to focus on them in the last few years precisely when I started to understand that the research I was engaged in (which is on state violence and mass violence in the Iranian 1980s) was an immutable “red line” in two ways. Firstly, it touched upon the legitimacy and the narrated genesis of the Islamic Republic of Iran as being the democratic incarnation of the sovereign will of the revolutionary Iranian people – a narrative undermined by the history of state violence in the following decade. Secondly, this history of violence was not just a red line, i.e., a forbidden subject. It was one of the main processes through which the very mechanisms of the “red lines” were constructed.

When I say that red lines were built through state violence, I do not mean that they were drawn with the Kalashnikovs of young Basijis, but what I refer to is a long and violent process of ideological construction, which was built on several lines of force. On dimension is that of affects, in particular fear in the production of social indifference through policies of terror and executions. Another dimension is that of values, in particular “moderation, prudence and patience”, to paraphrase the slogan of reformist president Khatami. Through an economy of clemency and cruelty towards political dissidents who were made co-responsible for the level of violence exerted against them, and consequently co-responsible for the level of political violence in society, the values of stubbornness (pâfeshâri) and radical opposition inherited from the 1979 revolution have been undermined as toxic behaviors and signs of immaturity. The legacy and covered-up memories of state terror in the 1980s have produced a switch, by which the denunciation of the violent genesis and criminal nature of the post-revolutionary state was assimilated to an aggressive position, while the support of state denial and the acceptance of the red lines were defined as the pacifist position. A third pillar of the ideological construction that shaped political and social order under the Islamic Republic of Iran was the collective identity built through the figures of the martyr and the enemy, both external and internal.

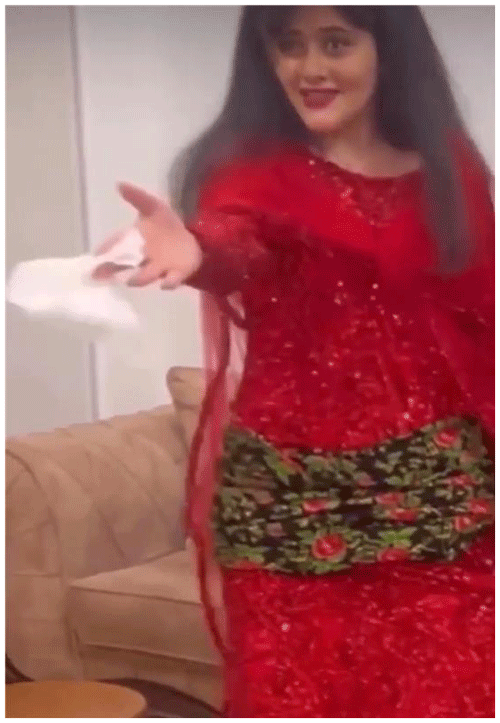

This quick cartography of power is precisely what the current acts of defiance in Iran, such as the unveiling of women, are attacking, corroding and reversing. The absence of fear, as well as the politics of attachment towards the families of the executed, challenges indifference and atomization. Frontal opposition and “agonistic politics” (Athanasiou, 2017) reverse the reformist values of prudence and moderation. The celebration of life, particularly through dance, neutralizes the figures of the enemy or the martyr. This was best shown when a video of Jîna Mahsa Amini, dancing in a red traditional Kurdish dress, circulated right after her murder by the morality police on 16 September 2022 (Fig. 6). The dancing body of the young woman is that of a life raptured, but not a martyr, and that of a Kurd, but not an enemy.

Crossing the red lines and inventing a repertoire of protest through staging this defiance also imply that protestors have broken out of the cognitive and emotional mechanisms that have organized the social pact since 1979 – since before most of the protestors were born. New moral economies of dissent are reconfiguring the space of meaning in which all further developments will henceforth be received and understood (Makaremi, 2023a).

I would like to pursue this reflection through another gesture: the whistling and booing of the national soccer team (Fig. 7). This act too becomes a marker of defiance, another signifier in the language of political antagonism: on 29 November 2022, a Kurdish man who honked to celebrate the disqualification of the Iranian team at the World Cup in Qatar was killed with a bullet in the head by a member of the security forces. The FIFA World Cup began in Qatar on 21 November 2022. The Iranian national team had refused to sing the national anthem at the first match in Doha. But their very presence was seen as a betrayal. They suffered a humiliating defeat at the hands of England and were disqualified by the United States. In this World Cup competition, it was not Iran that lost: it was the Islamic Republic of Iran team. However, for many Iranian viewers, aversion had been giving way to more troubled and painful feelings. This defeat was also a spectacle that many did not have the nerves to watch. For those who have been accustomed for decades to seeing the flag of the Islamic Republic of Iran as their country's flag, it is an emotional wrench. One of the main successes of this power is that, at the end of the first 10 years of its foundation, two collective identities coincided perfectly: that of Iran and that of the Islamic Republic of Iran. I have been studying this successful mechanism in the last decade (Darabi and Makaremi, 2019; Makaremi, 2018).

Figure 7The national soccer team of the Islamic Republic of Iran, FIFA World Cup, Qatar, November 2022 (credit: anonymous).

Figure 8Iranian supporters holding a Woman, Life, Freedom banner during a match disputed by the Islamic Republic of Iran national team at the FIFA World Cup, Qatar, November 2022 (credit: anonymous).

As mentioned earlier, theocratic power has achieved this process thanks to a patriotic recast during the war against Iraq, red lines superimposing national borders and political limits, unifying figures of the martyr and the enemy, and a controlled rewriting of history. Since fall 2022, Iranians have been experiencing the dismemberment of this coincidence. Their rejection of the national soccer team embodied this fundamental, revolutionary rupture (Fig. 8). It seems to me that the political form “Islamic Republic of Iran”, as I knew and studied it, ceased to exist in that stadium, under those whistles. This divorce between the state and the street makes palpable the separation between ”Iran” and its leaders. The myths of popular sovereignty having collapsed, the latter are represented as a clique “occupying” what the dissidents consider to be the “real” country. Ever growing fragments of the Iranian society, including much of the former popular basis of the state, share the feeling of being colonized from within, framing their experience of domination in reference to a political condition shared by the outlying provinces. While this experience of colonization was inaudible and marginal for decades, they surfaced through the 2022 uprisings – which started with the killing of a Kurdish woman and were marked by the massacre of Baloch protesters in the city of Zahedan on the “bloody Friday”, 30 September.

“We'll fight, we'll die, we'll get Iran back”, chanted the demonstrators in 2022 and 2023. Strangely enough, what became Gen Z's cry from the streets would have been considered, until then, the fossilized discourse of diasporas stuck in their defeats by Khomeini 40 years ago. A question remains unanswered: what is this “real” country, this occupied Iran that needs to be liberated? How can a common referent be constructed by a transnational Iranian society that is strangled internally and asphyxiated in the diaspora by a lack of daily, concrete contact with the country?

The third image brings us towards the end of the Woman, Life, Freedom uprising as we have known it in its first stage of eruption, in fall 2022 and winter 2023 (Fig. 9). February 11 is the national holiday celebrating the victory of the Iranian Revolution in 1979, and the return of Ayatollah Khomeini from his exile in France, in order to take the lead of the revolutionary movement that expelled the Shah in January 1979. In the streets of Europe and North America, the Iranian diaspora organized rallies to mark 11 February 2023: concerts and speeches in support of the Woman, Life, Freedom movement.

Figure 9Demonstrators holding an inflatable plane that represents Khomeini's flight from Paris to Tehran in February 1979, with attached jib ropes, Paris, 11 February 2023 (credit: anonymous).

These counter-festivities were intended to produce images transmitted by satellite into Iranian homes, antagonistic to those broadcasted by Iranian public television in celebration of the Islamic revolution. On the stage set up at the Place des Invalides in Paris, questions remained unanswered however. Were people claiming a different memory of the February revolution? Were they reclaiming, through this revolution, a legacy of insurrectionary power and revolutionary possibility? Or were they celebrating an opposition to this event? Were they returning together to the point where everything turned upside down? Is it possible to consider a part of history as a mistake? Can erasing an event constitute a political program? At a pensioners' association demonstration in Tehran in fall 2022, people in their sixties humorously chanted “We screwed up!” (Go khordim). They were talking about the February revolution of 1979. Red lines, national borders and political boundaries have long kept the counter-memories of this revolution below the threshold of audibility in Iran. But these counter-memories are multiple: as the Islamic Republic of Iran's fictions of power crumbled, they have resurfaced all together in a cacophony dominated by the monarchist discourse, supported by major Persian-speaking media abroad.

Finally, these counter-memories raise a question (also at the heart of my work in historical anthropology) that is fundamental for understanding the possible evolution of the Woman, Life, Freedom uprising, linked to the alternative political projects to that of the Islamic Republic: What is to be done with the revolutionary experience of 1979? And how do discourses, memories and fictions on the genesis of a power shape the rules of political participation, shape the scope of citizenship, encircle our political imagination and determine the very possibility of expanding it?

Underlying research data available online (links to websites, databases, paper and audiovisual archival collections containing original data) will be displayed in a database, which is currently under construction. Persistent URLs and metadata produced according to RIC-CM standards will be available online. This database, called “the (counter)archives”, will be available on the website of the project upon completion: http://www.off-site.fr (last access: 20 December 2024). Data derived from oral interviews and digital ethnographic observations cannot be widely disseminated and openly shared with interested persons, because such disclosure is potentially dangerous to the safety of the interviewed persons. Interviewees include victims of state violence: former political prisoners and family members of executed political prisoners and members of ethnic and religious minorities that have been specifically targeted by state repression and violence (such as Bahais, Kurds, Iranian Arabs). The data collected through these ethnographic interviews may contain personal data revealing racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, and religious or philosophical beliefs of participants. This information is shared voluntary by the participants during their interview. These personal data cannot be disclosed outside the project without the consent of the participants. All personal data which will be made available for reuse will be prepared for that purpose, with strict anonymization and deidentification of data sets to minimize the risk of reidentification. These data will be stored and secured in order to protect participant privacy and reduce the risk of data misuse.

The author has declared that there are no competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

I wish to thank Hanna Hilbrandt and Nadine Marquardt for their invitation to this forum. A portion of this article draws upon material from my book Woman! Life! Freedom! Echoes of a Revolutionary Uprising in Iran (Yoda Press, Delhi, 2025, forthcoming). I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my publisher, Yoda Press, for granting me permission to include this content. Their support and commitment to the dissemination of my work have been invaluable.

Anonymous: “Revolution is closer to you than your jugular vein”, Cherk Nevis, Telegram, 3 October 2022, https://t.me/cherknevis, last access: 5 May 2023.

Arendt, A.: The Origins of Totalitarianism, NY: Schocken Books, ISBN 978-0156701532, 1951.

Athanasiou, A.: Agonistic Mourning: Political Dissidence and the Women in Black, Edinburgh: University Press, ISBN 9781474420143, 2017.

Benedict, R.: The chrysanthemum and the sword: Patterns of Japanese culture, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 9784805301135, 2005.

Butler, J.: 2004. Precarious Life. The Powers of Mourning and Violence, London: Verso, ISBN 9781844670055, 2004.

Darabi, H. and Makaremi, C.: Enghelab street, a Revolution through Books: Iran 1979–1983, Leipzig & Paris: Spector Books/Le Bal, ISBN 9783959052627, 2019.

Evans-Pritchard, E. E.: The Nuer: A description of the modes of livelihood and political institutions of a Nilotic people, Oxford: Clarendon Press, ISBN 9780195003222, 1940.

Forte, M. C.: The Human Terrain System and anthropology: a review of ongoing public debates, Am. Anthropol., 113, 149–53, https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1548-1433.2010.01315.X, 2011.

Fuentes, M. J.: Dispossessed lives: Enslaved women, violence, and the archive, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 9780812248227, 2016.

Jourde, C.: The ethnographic sensibility: Overlooked authoritarian dynamics and Islamic ambivalences in West Africa, in: Political ethnography: What immersion contributes to the study of Power, edited by: Edward, C., Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 201–216, ISBN 9780226736761, 2013.

Kunth, A. and Makaremi, C.: Les griffures du pouvoir, Sensibilités, Histoire, critique et sciences sociales, “les paradoxes de l'intime”, 6, 48–68, ISBN 9791095772-613, 2019.

Loraux, N.: The divided city: on memory and forgetting in Ancient Athens, Zone Books, ISBN 9781890951085, 2002.

Makaremi, C.: State violence and death politics in post-revolutionary Iran, in: Destruction and Human Remains: Disposal and Concealment in Genocide and Mass Violence, edited by: Anstett, É. and Dreyfus, J.-M., Manchester: Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0719096020, 2014.

Makaremi, C.: Violence d'État et politiques du déni en Iran: les tracés du pouvoir, Monde Commun, 54–75, ISBN 9782130809159, 2018.

Makaremi, C.: Hitch. An Iranian Story, Alter Ego Production, https://vimeo.com/ondemand/330467/546495156 (last access: 27 December 2024), 2019.

Makaremi, C.: Crossing the Red Lines, Society for Cultural Anthropology, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/crossing-the-red-lines (last access: 7 May 2024), 2023a.

Makaremi, C.: Femme! Vie! Liberté!: échos d'un soulèvement révolutionnaire en Iran, Paris: La Découverte, ISBN 9782348080449, 2023b.

Robben, A.: Iraq at a distance: what anthropologists can teach us about the war, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 9780812242034, 2010.

Stoler, A. L.: Carnal Lnowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule with a new preface. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, University of California Press, ISBN 9780520262461, 2010.

Weizman, E.: Introduction: forensis, in: Forensis: The architecture of public truth, Berlin and London: Sternberg Press, ISBN 9783956790119, 2014.

Based on the case of Iran, this research seeks to change our ways of studying “locked” societies, by adapting our methods and episteme to the global circulation of norms, data and people. Through the anthropology of the state and violence, archive ethnography, and the use of new technologies, it experiments with trans-disciplinary methods in the production of empirical study off-site, in order to fill a substantive gap in scientific knowledge on the first decade following the Iranian Revolution (1979–1989) and how its legacy reappears in today's politics of memory. By classifying and reviewing available sources in a digital “counter-archive”, the project will establish a genealogy of post-revolutionary violence and state formation in Iran and make this documentation available for further research. It will also document and analyze the memory politics linked to this foundational past and how they redefine the boundaries of political participation. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant no. 803208). See http://www.off-site.fr (last access: 20 December 2024)