the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The open society and its life chances – from Karl Popper via Ralf Dahrendorf to a human geography of options and ligatures

Olaf Kühne

Laura Leonardi

Karsten Berr

In recent decades, geography in the German-speaking world has been strongly oriented towards Anglo-Saxon and French concepts. For some years now, efforts have been emerging to consider the potential of German language, not only philosophical but also sociological and anthropological traditions of thought for human geography in Germany and beyond. This article considers two thinkers from the German-speaking world who have dedicated themselves to defending the open society: Karl Popper and his student Ralf Dahrendorf. In particular, the operationalization of open society considerations in Ralf Dahrendorf's conflict theory shows great potential especially for human geography research, as conflicts in the use and design of material spaces as well as over conceptual versions of spaces are commonplace. This thesis gains its current validity not least from the resurgence of authoritarian and totalitarian ideas that reject the achievements of open societies and always have spatial implications. It is therefore time to turn to the four central theorems of the two thinkers: (1) Popper's three worlds theory and (2) the concept of open society and (3) Dahrendorf's concepts of life chances and (4) conflict regulation.

- Article

(1774 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

In recent decades, geography in the German-speaking world has been strongly oriented towards Anglo-Saxon concepts as well as towards French concepts imported via Anglo-Saxon discourse (Korf, 2021). For some years, however, efforts have been made to realize the potentials of German-speaking philosophical and sociological–anthropological traditions of thought for human geography, in Germany and beyond. To date, phenomenological approaches and the potentials of the Frankfurt School have been explored in particular. In what follows, we will look at two other thinkers from the German-speaking world who have dedicated themselves to defending the open society: Karl Popper and his disciple Ralf Dahrendorf. Especially the operationalization of the open society considerations in Ralf Dahrendorf's conflict theory shows great potential for geographical research, as conflicts are commonplace in the use and design of material spaces, as well as around conceptual versions of spaces.

Karl Popper's early work, The Open Society and its Enemies, is updated to this day in philosophy, sociology, political science, pedagogy, and others, but it remains largely (nationally and internationally) without a large resonance in human geography. The discursive dominance of post-structuralist and neo-Marxist approaches with their high normative components has become too great in recent years (on the state of German human geography in particular: Korf, 2019, 2021). The same is true for the work of Popper's student Ralf Dahrendorf, whose contributions to role and conflict theory, the concept of life chances, and political sociology have found great resonance nationally and internationally, not only in sociology (Dahrendorf, 1959, 2017, 1972, 1979, for classification: Leonardi, 2014; Kühne and Leonardi, 2020), but also in human geography. Especially in the context of increasing social conflicts, with their spatial contents, not least the resurgence of authoritarian and totalitarian ideas, which reject the achievements of open societies and always have spatial implications, the time seems to have come for German-speaking and international human geography to take a closer look at the thinkers originating from Austria (Popper) and Germany (Dahrendorf).

Therefore, our article aims to show the relevance of the thinking of Karl Popper and Ralf Dahrendorf in the present, especially for contemporary human geography. The previous impact – especially of Karl Popper's understanding of material world, individual world and cultural world – will be treated in a concise way, to the degree it is necessary for the understanding of our Popper review. A more extensive history of impact would mean a separate publication.

We begin our article with some notes on Karl Popper's understanding of the open society, which Ralf Dahrendorf makes the central basis of his sociology. Then we introduce Popper's theory of the three worlds and present a concept to operationalize it for the research about spaces. Ralf Dahrendorf draws constitutively on Popper's ideas on the open society in his concept of life chances, which we present in the following. Some examples of spatial conflicts show how the theoretical strands elaborated on so far – complemented by Dahrendorf's conflict theory – can be profitably applied to current issues in dealing with space. On this basis, we present the relevance of Popper's and Dahrendorf's ideas for international spatial research and synthesize the results in a conclusion with a view to current social developments.

The Open Society and its Enemies (Popper, 2011 [1947]; for an introduction also see Zimmer, 2019; Zimmer and Morgenstern, 2015; Brunnhuber, 2019; Corvi, 2005 [1997]; Boyer, 2017 [1994]) was written by Karl Popper under the impression of the actions of and the confrontation with the totalitarian regimes of National Socialism and Stalinism. In this work he traced the line of totalitarian thinking of National Socialism and Stalinism via Hegel back to Plato, in the case of socialism via Marx. He contrasts totalitarian, closed societies with the idea of an “open society”. Its central characteristics lie in the willingness to change and the ability to shape it: no collective teleologies determine the development of society but rather individuals who are willing and socially enabled to make decisions in order to try out something new (he will elaborate on the central importance of the individual later in his three worlds theory; see the following section). The open society presupposes freedom of opinion as well as the ability and opportunity to put forward one's own opinion. This freedom, in turn, is central to the competition for the most suitable solutions to concrete challenges. This core idea of an “open society” is also found in his philosophy of science, for “such knowledge is denied us. Our knowledge is a critical guessing; a web of hypotheses; a tissue of conjectures” (Popper, 1989:XXV). Popper characterizes both fascism and Marxism as a variation of the Hegelian principle. Hegel's “spirit” is thereby replaced either by “matter and material and economic interests” (Popper, 1992:74) (Marxism) or by a vulgar Darwinian understanding of blood and soil, in which instead of “spirit” “blood is the self-evolving essence” (Popper, 1992:74). Instead of “its `spirit,' the blood of a nation determines its essential destiny.” (Popper, 1992:74). Popper accuses Marx of “misleading countless intelligent people into believing that the scientific treatment of social problems consists in the making of historical prophecies” (Popper, 1992:97).

In the tradition of Popper, Dahrendorf repeatedly takes a critical look at Karl Marx. Regarding his view of history, he already states the following in his dissertation:

The birth of communism appears here [in its inevitability; authors' note], as it were, as the work of natural forces or of divine foresight; and the question has often been asked what space this “inevitable” process still leaves out for man, his actions and his goals (Dahrendorf, 1952:13).

Whereas for Karl Marx “man” was “in a very radical sense a social being” (Dahrendorf, 1952:65), Dahrendorf (like Popper) focuses on the possibility of the individual to modify social structures. He sees historical materialism with its teleological understanding of history as historically resistant: the clash of class struggles in capitalism has failed to materialize as a result of the differentiation of class boundaries. Furthermore, he states that because of the “failure of Marxism to explain National Socialism” (Dahrendorf, 1968:287), it is difficult to argue that “the success of the Nazis was the victory of an oppressed class” (Dahrendorf, 1968:287). Above this, he states that because of the “failure of Marxism to explain National Socialism” (Dahrendorf, 1968:287), after all, it would be “difficult to argue that the success of the Nazis was the victory of an oppressed class” (Dahrendorf, 1968:287). In this respect, Dahrendorf attests to Marx's important contributions to the understanding of society and its development, such as the concept of class and the determination of the normativity of conflict, but he criticizes utopianism with its tendency towards totalitarianism, as well as the resulting low esteem for the individual (which Popper also criticized), leaving no room for individual and subjective agency.

Following Popper, Dahrendorf (1972:44–45) establishes the central difference between democracy and totalitarianism:

Totalitarianism is based on oppression (often passed off as a “solution”), democracy on the regulation of conflicts (Dahrendorf, 1972:44–45).

From which, in consequence, a fundamental difference results:

Democracy is above all a regulation of succession which, in the most favorable case, can lead to rapid changing of the guard without bloodshed and even unnecessary bad blood (Dahrendorf, 1995:58).

Currently, utopian thinking – which as Dahrendorf (1980:88) notes “is always illiberal, because it leaves no room for error and correction” – is gaining momentum again. It is in the form of socialist ideas, whose two dozen or so attempts at implementation have at least ended in authoritarian regimes, in the form of nationalist populist movements, as well as in the form of ecological–political movements (Strohschneider, 2020; Eichenauer et al., 2018) and in the form of ecological utopias, which represent a teleological idea of a harmonious synthesis of “man” and nature (Dobson, 2007; Schultz, 1998). From their teleological consciousness, their own (moral) superiority over the “unbelievers” is derived, which in turn forms the basis for paternalistic via therapeutic up to freedom of movement radically restricting measures (Ackermann, 2020; Grau, 2017, 2019; Kostner, 2019). Common to these understandings is also the endeavor to restrict the play of ideas in the competition for the most suitable approaches to mastering concrete challenges by means of the closure of discourses (Strohschneider, 2020; Kühne et al., 2021c).

Karl Popper's three worlds theory (Popper, 1973, 1979 , 2019 [1987]; Niemann, 2019; Popper and Eccles, 1977) provides an approach for a conceptual structuring of the world between matter, individual consciousness, and the world of spiritual contents. It also provides approaches for understanding the processes occurring between these levels. Finally, it facilitates the assignment of theoretical perspectives on the relations between matter, individual consciousness, and the world of cultural contents (cf. also Weichhart, 1993, 1999; Kühne, 2020, 2022).

Karl Popper's theory of three worlds – and from it, the theory of three spaces or three landscapes – joins a series of divisions into three levels of space or landscape. Widely used in the current poststructuralist mainstream is Henri Lefèbreve's (1974) outline of his three spaces (which has also been widely disseminated in the Los Angeles School of Urbanism). This design is based in Marxism and has not least teleological residues, insofar as it does not seem commensurable with a design in the tradition of Popper and Dahrendorf (a comparison of the concepts, however, is provided by Gryl, 2022). The approach of the three landscapes by Jackson (1984) formulates a temporal sequence of (materially understood) pre-modern, early modern, and highly modern landscapes. In this respect, the two theories can be thought in complementary terms (Jackson's understanding might add an enhanced temporality to Popper's). There is, however, a stronger connection to the theories of Anthony Giddens and Benno Werlen. Before making this comparison, however, we will briefly introduce Popper's three worlds theory.

An approach to spaces, following the guideline of the three worlds theory, can provide an analytical framework for understanding conceptions of space, without already wanting to make a specific categorization of conceptions of space. To World 1 Popper assigns living and non-living bodies; to World 2 he subsumes contents of consciousness, that is, individual thoughts and feelings, such as “perhaps also of subconscious experiences” (Popper, 2018 [1984]:82); to World 3 he assigns “all planned or intentional products of human mental activity” (Popper, 2019 [1987]:17; emphasis in original) for example mathematical theorems, as well as largely socially and culturally shared understandings of space, landscape, theory, and, of course, the three worlds theory itself. In this conception, the so-called “reality” thus “consists” of three interrelated “worlds”, without a specific entity being disjunctively assignable to only one specific “world”. That is, entities can be assigned to several worlds – for example, a gravel pit is part of both World 1 (as a material object) and World 3 (as a carrier of cultural and social meanings) as well as World 2 (as an individual content of consciousness).

In German-speaking human geography, Karl Popper's three worlds theory more widely received (Weichhart, 1999; Werlen, 1986, 1997; Zierhofer, 1999, 2002; Schafranek et al., 2006; Hard, 2002). Especially in Benno Werlen's draft of his theory of action, the thinking of Karl Popper is actualized in a direct way and in an indirect way: in a direct way when he takes Popper's theory of three worlds as a basis for his considerations on the structuring of world and in an indirect way when he draws on the structuration theory of Anthony Giddens. Karl Popper (1992) formulates with his methodological individualism on the one hand the explanation of individual actions from social action situations and on the other hand the development of social phenomena on the basis of individual actions. Giddens (1979) explicitly takes over this idea from Popper in his structuration theory. In doing so, he accuses Popper, excluding his concept of situation logic, of leaving social structuring of action unconsidered, whereby Giddens' theory of structuration hardly goes beyond the mutual structuring of individual and society formulated by Popper (Diefenbach, 2009) and Peter Weichhart's concern to take the material world adequately into account in social geography. Both drafts focused on the conditionalities of human action, in Benno Werlen's case with a focus on the social conditionalities, in Peter Weichhart's more strongly in consideration of the conditionalities of the material world. Both approaches to Popper's theory were seen as strongly considering ontology and statics, less so the epistemological and dynamic dimension of Popper's theory.

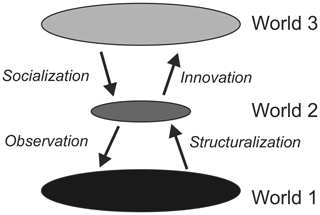

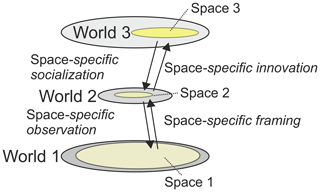

Moreover, it is crucial that the three worlds interact with each other, which is not least pointed out by Benno Werlen (1986) in addition to Popper's approach by the phenomenology of Alfred Schütz (Schütz, 2004 [1932], 1971 [1962]; Schütz and Luckmann, 2003 [1975]). At the center of these interactions is World 2 of individual consciousness, insofar as it is respectively fed back to World 1 and World 3. People have a body (World 1), a consciousness (World 2), and access to the world of cultural content (World 3). World 2 is linked to World 3 in that an individual is introduced to social knowledge, patterns of interpretation, and evaluation (socialization) and has the opportunity to socially embed new knowledge, patterns of interpretation, and evaluation (innovation). With World 1, World 2 is connected by individual observation, at the same time it receives a structuring frame for its activities by its body and corporeality, from which it cannot detach itself (for more details, see Kühne, 2020; Kühne et al., 2021a) (see in overview Fig. 1). In this case, freedom does not refer to an individual abstracted from the context in which they are embedded. Rather, it refers to the structural conditions that enable a social actor to pursue certain goals. This, then, is the instrumental aspect of freedom, the role that the individual actively plays in order to consider their life project (Popper, 2011 [1947]; Dahrendorf, 1979, 2002).

If this model of the three worlds is transferred to an analysis of spatial contexts, spatially arranged animate and inanimate bodies form the physical basis of “Space 1” as part of World 1. “Space 2” correspondingly comprises individual experiences, conceptions, sensations, feelings, value and norm conceptions, etc. of and about space (as part of World 2). “Space 3” refers to the social constructions of space and the social conventions regarding patterns of interpretation and evaluation of space (Fig. 2).

The concept of life chances, which Ralf Dahrendorf set out in his book of the same name in 1979, is an expression of his manifold preoccupations with role theory, his critical engagement with Marxism, and the structural functionalism of Talcott Parsons, as well as an expression of his liberal understanding of the world. Ralf Dahrendorf was – as Kocka (2004:151) pointed out – “a social scientist and as such the author of classic sociological texts, a political intellectual and intellectual politician, German and English, founder and director of scientific institutions, lifelong journalist, internationally sought-after consultant and speaker, honored many times” (more information about his life can be found in Dahrendorf, 2002; Meifort, 2017).

The open society for Ralf Dahrendorf – following on as well as revising Popper's concept – is the necessary condition for liberty and therefore for the expansion of life chances: only the “openness” of society makes it possible to be the place where social conflicts can be regulated and play a role in widening life chances.

The year 1989 was an opportunity to revisit Popper's concept of the open society, which Dahrendorf adopted in his social analysis from an early age, but he was keen to emphasize that

the concepts of closed and open societies should not be taken as mere phrases or hypostatised principles of political philosophy. They can give useful indications for the analysis of social transformations in their socio-political and socio-economic core (Dahrendorf, 2005:26).

This clarification makes the concept operational, since in empirical reality societies show different degrees of closure and openness, and the challenge for social analysis is to grasp the implications for life chances.

The concept of life chances, for Dahrendorf, makes the normative concept of liberty “operational”. Necessary and sufficient conditions for their realization can be identified:

we distinguish between liberty and freedom, or rather between necessary conditions of freedom and sufficient conditions. The necessary conditions define the state in which certain life chances must be, the sufficient conditions denote a behaviour that can be defined as an incessant attempt to extend life chances; an attempt that does not, however, contain any list of necessary life chances (Dahrendorf, 1981:209).

Dahrendorf takes up the Weberian concept of chance and critically reinterprets it to define life chances. According to Weberian meaning, chance is constitutive of relationships and social formations; it is related to the choices that subjects are able to make between alternatives of action and incorporates the dimension of sense (Sinn) (Mori, 2016). Chance refers to the notion of social action: it is not something random, nor is it ascribable to prescriptive elements of social structures. It includes the possibility of something unexpected, non-predetermined, something which we refer to as emergence (Dahrendorf, 1981:15; Popper, 2011 [1947]). Max Weber's life chances have been transposed according to very different meanings within sociological theory. Life chances in Max Weber are associated with Lebensführung, a concept that has been lost in the English translation and replaced by the concept of lifestyle – also widely spread in other non-Anglo-Saxon sociological literature (Mackert, 2010) – and it has been stripped of the reference to the action of choice, of self-realization and autonomy that connotes the notion of conduct of life. Consequently, life chances also lose their connotation, brought back to socially structured conditioning. Merton is the main interpreter of this understanding of life chances, which he takes from Weber but makes coincide with the concept of opportunity structure indicating the scale and distribution of conditions that provide various opportunities for individuals and groups to achieve determinable outcomes (Merton, 1995:25). In doing so, he also removed from the concept of life chances the link to social conflict, which connotes the Weberian notion. Weber's conflict theoretical perspective suggests that “life chances” are a scarce good, the distribution of which occurs through struggle and competition, which (also) takes place in the form of social closure processes (Mackert, 2004). Life chances, therefore, are not only about the unequal distribution of resources but also about how social actors mobilize to reduce the access of others to options while realizing their own goals.

Dahrendorf's reformulation of the concept of life chances at the center of the modern social conflict aims to challenge the view of the value of choice in a quantitative and meaningless sense, as acte gratuit. The reference is to a concept of active liberty, which goes beyond the distinction between negative and positive freedom (Berlin, 1995 [1969]) and seizes the participatory aspect of democratic participation (Sen, 1994:87), related to the action and the degree of autonomy of the individual subjects. In this case, freedom does not refer to an individual abstracted from the context in which he is embedded. Rather, it refers to the structural conditions that enable a social actor to pursue certain goals. This, then, is the instrumental aspect of freedom, the role that the individual actively plays in order to consider their life project. Thus at the instrumental aspect of liberty, the role that they actively play and their life project are taken into consideration. Here the similarity to Giddens' theory of structuration becomes clear – which again is not surprising, since Giddens and Dahrendorf are based on Popper's approach of methodological individualism, although Dahrendorf makes his constitutive reference back to Popper more explicit (see, e.g., Kühne and Leonardi, 2020; Diefenbach, 2009). Nevertheless Giddens' utopian realism has a normative scope in its theoretical content that we do not find in Dahrendorf's anti-utopian approach: this emerges clearly in the debate on the “third way” (Leonardi, 2020). In analyzing the processes characterizing globalization, in fact, Giddens sees potential for expansion and fewer constraints on individual agency, without taking into account the unconscious processes informing choice and decision-making and the obstacles arising from power relations. In equating reflexive and experience-driven modernization, Giddens underestimates what Dahrendorf's analysis emphasizes instead: the pluralization of rationalities and knowledge agents and the key role of manifest and latent types of unconsciousness, which constitute and establish the discontinuity of “reflexive” modernization in the first place (Greener, 2002:303).

Life chances are possibilities for individual agency and realization of individual capabilities. They are a function of options, “alternative possibilities of choice of action in social structures”, and of ligatures, “memberships, relationships that provide meaning to action” (Dahrendorf, 1988:17), a function we can express by the formula (Munro, 2019:9). The modern social conflict has sought to strike a balance between the two components of life chances by advancing both through the enlargement of social citizenship. Options refer to the horizon of action, decisions open to the future, while ties as social relations constitute the foundations of action. Options are, in turn, a combination of entitlements and provisions. Dahrendorf borrows from Amartya Sen (Dahrendorf, 1989:14–15) the notion of entitlements:

A relationship to persons and things by which their access to them and their control over them is legitimate (Dahrendorf, 1989:14).

Rights to vote in democratic elections, education, social protection, and real wage are all concrete examples of what entitlements are. They can be thought of as “entrance tickets”. Entitlements open doors to individuals, but they also draw boundary lines and constitute barriers if they are not universally guaranteed (Dahrendorf, 1989:16). Provisions have a quantitative aspect, more economic than legal and political than entitlement aspects, and they are the bundle of alternatives in certain areas of activity (Dahrendorf, 1981). Moreover, life chances incorporate ligatures, since the individual is placed within “ties dense with emotional connotations” (Dahrendorf, 1981:42) that are configured as social relations, which give meaning, sense, and anchorage to social belonging. Dahrendorf employs the surgical term “ligatures” to express a concept that also serves to distance himself from those who, by employing the term “ties” or bonds, recall a kind of “nostalgia” for the community: he, in fact, considers the concept of community very close to that of a “closed society” (Dahrendorf, 1988:151).

Ligatures form “in a sense the inside of the norms that guarantee the social structures in the first place” (Ackermann, 2020:141); they are highly charged emotionally or morally. The constant tension between the components of life chances is linked to the relationship between the economic sphere and the political and cultural spheres. In the terms of Popper's three worlds theory, it is clear that life chances, related to the individual dimension of consciousness, reflexivity, and feelings, finding realization in individual autonomy, are centered on World 2, but at the same time they are made possible by World 3 and are nourished by World 1.

For Dahrendorf, options and ligatures are in an interdependent relationship: ”Ligatures without options mean suppression, while options without ties are meaningless” (Dahrendorf, 1979: 51–52). However, while Dahrendorf assigns an unqualified positive significance to options for the development of life chances, his evaluation – as shown – remains ambivalent to contradictory. Ligatures are able to give meaning to options (the productive component for him), but they restrict the individual in obtaining and perceiving options (for example, not accepting educational opportunities because of religious ties). This poor differentiation of ligatures can be resolved by distinguishing between moral ligatures (i.e., those that prescribe courses of action in concrete situations) and ethical ligatures (i.e., those that enable moral ligatures to be reflected in their function and mode of action). The latter enable life chances; the former restrict them (Kühne et al., 2022).

Since the end of the real-socialist project in eastern central and eastern Europe, “change without violence” has been especially proposed under new conditions. After all, the social foundations and reference structures have changed. This means that the political and economic institutions that have allowed, through the institutionalization of conflict, the widening of life chances, are no longer adequate to perform this function. In modern society centered on the division between social classes, liberal democracy and so-called organized capitalism, rules, and norms have emerged (i.e., social dialogue, norms for electoral competition) that made it possible to institutionalize conflict, effective in preventing antagonism between collective social actors from manifesting itself with disruptive intensity and violence. Thus, conflicts appeared susceptible to being ordered, regulated, organized, and capable of guaranteeing change without bloodshed, as Popper put it. But the repeated and out-of-control crises that have emerged since the 1980s, the processes of individualization, cultural, and value change, and new social risks have brought back to the center the need to address the issue of conflict in a new way, in parallel with the emergence of new subjectivities, the dynamics of intersubjectivity, and mutual recognition that are linked to the new role of civil society, movements, and the idea of emancipation. There has been a historical decline in the central conflict that pitted workers against capital and shaped all community life, informing politics, the coherence of the social fabric, and intellectual discussion. Since then, new topics of discussion have come to the fore: for example, the relationship between the social and cultural spheres and between struggles against forms of inequality, for social justice, and those for recognition (Fraser and Honneth, 2003). In these new conflicts, the cultural dimensions are much more pronounced than in the conflicts that were the driving force of industrial societies. The numerous reproductive crises are perceived individually and collectively as a threat to one's autonomy and right to decide on one's own life, and an awareness of risk grows, but it takes on very different meanings and produces different effects. This produces social conflicts made up of reactions of protest, of contestation, of antagonistic social groups, which makes it difficult to analyze and interpret how they can be settled. In light of these societal changes Dahrendorf developed the conflict theory centered on life chances.

Dahrendorf was a social scientist attentive to the rigor of method for analysis: for him, a good method implies that one does not come to prefigure an outcome but leaves the horizons open. By respecting this principle the open society can be configured as an open space in which to engage in “strategic planning” of life chances (Dahrendorf, 1989). At times Dahrendorf uses the term in the Popperian sense of “social engineering” – far from the current meaning and common sense – as opposed to dogmatic planning, which is does not propose “models” to be pursued. It also does not mean proceeding with palliative and uncoordinated measures; it means making decisions that can have lasting effects, taking a long-term perspective.

Ligatures and options are not equally distributed in the relations between the worlds (see Kühne et al., 2021c, 2022, for more details); thus the influence of Worlds 1 and 3 on World 2 occurs primarily in the form of ligatures. Social conventions (from World 3) are mediated to consciousness. The material restrictions of World 1 are made clear to consciousness, especially as a result of the bodily constitution of the human being (thereby the principle of bodily exclusivity of Space 1 occupation in particular has a strong structuring effect on action). Options arise primarily in the striving for effect in the relations of World 2 to Worlds 3 and 1. Thereby, also spatial ligatures are not limiting alone; rather they are the basis for options. Thus, the impact of World 3 on 2 does not only visualize the “annoying fact of society” (Dahrendorf, 2006:21), but it represents the basis for innovations; after all, it enables the individual to develop interpretations that deviate from social conventions.

In this part, we will use the example of spatial conflicts to illustrate how the three worlds theory is suitable as an analytical basis for the study of social conflicts and how these can be brought to a settlement, which in turn can contribute to an increase in the openness of a society.

The different demands on Space 1 formed by individual Space 2 in pursuit of life chances under the influence of Space 3 are sometimes contradictory and conflicting among themselves. The usually existing reconnection to Space 3 turns these spatial conflicts into social conflicts (generally on the structure of such conflicts: Kühne, 2020). Social conflicts are rooted in structural contradictory references between parts of a society:

A conflict should be called social if it can be derived from the structure of social units, i.e. if it is supra-individual (Dahrendorf, 1972:24).

This implies that individually psychologically conditioned conflicts and also conflicts between societies remain excluded from the explanatory scope of Dahrendorf's conflict analysis (Niedenzu, 2001). Dahrendorf's conflict theory can be located socially at the societal meso-level, spatially in subnational contexts. The number of such conflicts has increased in recent years, on the one hand due to the increase in land use conflicts and on the other hand due to the pluralization of society into exclusivist operationalizing units of discourse (Kühne et al., 2021c; Ackermann, 2020; Flaßpöhler, 2021; Grau, 2017).

This is particularly evident in conflicts over the expansion of facilities for the generation and transmission of renewable electricity and in relation to urban renewal measures, the extraction of mineral resources, the expansion of infrastructures for mobile Internet, rail infrastructure projects, etc. (among many, Leibenath and Otto, 2014; Gailing and Leibenath, 2017; Kühne and Weber, 2018; Jenal et al., 2021; Weber et al., 2018). In terms of life chances, these types of conflicts are emblematic of a situation in which options are meaningless and there is room for anomie. The terrain is fertile for a moralization of the conflict to fill the void left by the absence of ligatures (which could give meaning to the conflict and allow it to be regulated). Space is an essential component of life chances: in this article the interpretation and the claim of the appropriation of space are conceived as a ligature. This discards the options of renewable electricity because they are something unknown that alters the ligatures, experienced as a threat to the world as it is. This plays in favor of the closure of society, hence conservation. Conflict assessment is not contemplated here because some people struggle only looking for ligatures and not for options. This emerges precisely from the analysis of the formal aspects of conflict according to Dahrendorf's scheme. Dahrendorf identifies three phases of conflict unfolding (Dahrendorf, 1972): on the emergence of the initial structural situation. In the subsets in society (“quasi-groups”) the same latent interests are found, by which he understands “all positional behavioral orientations (role expectations) that establish an oppositional relationship between two aggregates of positions without the bearers of the positions necessarily being aware of them” (Dahrendorf, 1957:204). This is followed by the second phase of awareness of latent interests, characterized by group formation, which comes to light with an increasing outward presence, because “every social conflict pushes outward, to visible expression” (Dahrendorf, 1972:36). In the third phase, the organized conflict parties emerge openly “with a visible identity of their own” (Dahrendorf, 1972:36). The conflict takes on a dichotomized structure; the pro or con that has arisen does not tolerate any differentiations.

Contrary to other conflict theories (notably Parsons), Dahrendorf assumes that conflicts have constructive potential if they are subjected to settlement. The successful settlement of conflicts is dependent on four preconditions and two institutional frameworks (Dahrendorf, 1972, 1994; in more detail: Niedenzu, 2001; Matys and Brüsemeister, 2012; Kühne and Leonardi, 2020): firstly, conflict must be recognized as part of social normality, not as a norm-defying condition. Secondly, conflict regulation refers to the manifestations of the conflict, not to its causes. Thirdly, the possibilities of conflict settlement are positively influenced by a high degree of organization of the conflict parties. Fourthly, the success of the conflict settlement depends on the observance of certain rules, which must not favor any of the conflicting parties. The conflicting parties must be considered equal, and certain previously established procedural rules must be followed. The institutional framework describes two things: first, the existence of a third instance, which makes common binding specifications about the handling of conflicts and has the possibility to end the conflict externally if necessary, which Dahrendorf (1991:385) describes as “freedom under the protection of the law”. The second institutional prerequisite is the immutability of responsibility for decisions. In an open society, for example, this is done through the electorate's periodic review of the satisfaction of the elected representatives' record of leadership (Dahrendorf, 1969). If these conditions are not met, conflicts tend to become socially destructive. This is especially true when options are transformed into ligatures. Those with power over the “less powerful” (Paris, 2005) are in the form of privileges and transform them into ligatures. This has the side effect of limiting their generation of options (Dahrendorf, 1992, 2007; see also Strasser and Nollmann, 2010).

Particularly with regard to the changes in Space 1, conflicts are often not well regulated (for more information, see Kühne, 2018a, 2020; Kühne and Jenal, 2020; Kühne et al., 2021b; Weber et al., 2017, 2018). This has not least its reason in the aesthetic/emotional/cognitive synthetization of space into landscape in different modes. Mode a, as “native normal landscape”, is familiar and formed as normatively stable. In mode b, landscape is formed according to societal common-sense understandings, as present in school lessons, movies, coffee table books, social media, etc., comprising especially aesthetic and increasingly ecological stereotypes. In mode c, selective expert-like special knowledge stocks are added, which are acquired in particular by studying a subject and are shaped by the incorporation of subject-specific interpretation and evaluation patterns. Thus, the expectations towards Landscape 1 differ significantly according to the modes: Landscape 1c is subject to a norm of stability, Landscape 1b to the norm of correspondence to aesthetic or ecological stereotypes, and Landscape 1c to a strong subject-specific deficit view, which in turn is clearly subject-differentiated (e.g., among agricultural economists and landscape planners). The norms applied to Landscape 1 according to the different ones illustrate the complexity of spatial conflicts in general and landscape conflicts in particular. Moreover, the complexity of the different modal references makes it difficult to form organized conflict parties. The complexity of landscape, as well as the different perspectives, also facilitates the transformation of factual and procedural conflicts into identity and value conflicts, which is often associated with the moralization of the object of conflict, of the other conflict party as well as of the conflict itself (Kamlage et al., 2020; Eichenauer et al., 2018; Becker and Naumann, 2018). Moral communication, in turn, does not take place in the recognition of the legitimacy of the position of the other conflict party, but it implies one's own moral overvaluation, i.e., the devaluation of the other party. This in turn reduces the number of accepted world views and alternatives in dealing with landscape (1, 2 and 3), whereby it manifestly contradicts the central principles of the open society. The low regulatory capacity of spatial and landscape conflicts is made particularly explosive by the extensive absence of the “third party”, which is usually occupied by the state, which in turn is itself a party to the conflict in most spatial and landscape conflicts.

The preceding examples on space conflicts clearly point to the relevance of Karl Popper's understanding of the open society and his three worlds theory, as well as Ralf Dahrendorf's theory of life chances, especially in connection with his conflict theory, beyond the German-speaking world. Dahrendorf's success in Italy was truly peculiar. Already in the 1970s, his theory of class conflict was more successful there than in Germany and England. Dahrendorf himself sometimes wondered about the reasons for this and speculated that it was connected to the fact that, as it were, it was considered a kind of “Marxism without Marx” (Dahrendorf, 1985:237). In fact, he provided alternative tools for analyzing the “group conflicts, between subordinates and superordinates, in the university, in the church, in the judiciary” (Cavalli, 1973:100) that characterized Italian society in that historical period. His work Homo Sociologicus, for example, appeared at a time when Italian culture was struggling “between Croce's celebrations and an umpteenth crisis of Marxism” (Ferrarotti, 2010:10). Moreover, Dahrendorf's liberalism did not imply acceptance of the concept of freedom that is the heritage of classical liberalism, especially in its version of “negative freedom”. His social-democratic background and his studies at the London School of Economics and Political Sciences (LSE) made him particularly sensitive to the question of the relationship between freedom and equality, with regard to social citizenship and welfare, a central theme in the Italian debate. In Italian sociology, Dahrendorf's anti-utopian thought offered an epistemological and methodological alternative to the mainstream currents of thought:

The discriminating element is the flexibility of Dahrendorf's design, a flexibility that, in the possibility of going backwards, founds freedom as an essential component of the project […]. The flexibility lies in its being a stimulus for non-definitive discussion (Bovone, 1982:296).

Later, Dahrendorf fueled a broad debate in Italy, across many milieus and disciplines, with his analytical proposal summarized in the popular formula “squaring the circle” (Dahrendorf, 2009). From the mid-1990s until the first decade of the new century, his interventions on how to hold economic development, social cohesion, and political freedom together were the subject of an ongoing critical public debate. Up to the present, his topics have been intensively discussed and further developed (see, for example, Poggiolini, 2019; Corchia, 2019; Leonardi, 2019; Meifort, 2019; Kühne, 2019).

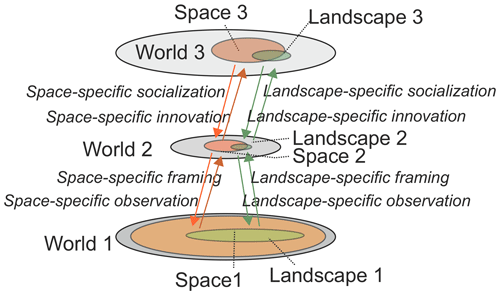

Popper's three worlds theory, operationalized for spatial and landscape research in the theory of three spaces or three landscapes, enables circumventing reductionist understandings of space (or landscape) in which either Space 1, 2, or 3 is recognized as existing or else two of them. The difference between space and landscape in this context has been discussed elsewhere. Central differences lie in the constitutive Level 3 of landscape, which differs not least from space (constitutive here is Level 1) because of its aesthetic binding, its moral, and thus normative charging. Also, landscape is not just a subset of space that is created by applying these conventions, so the metaphorical meaning (such as educational or party landscape) extends beyond the spatial. Also, this operationalization provides a framework for addressing the connections between Level (World/Space/Landscape) 1 and 2 as well as 2 and 3: the socialization of content from Level 3 into Level 2, as well as the innovation that can be introduced from Level 2 (especially in c-modal communication) into Level 3. Level 1 can in turn be shaped according to ideas of Level 2 and in turn structures Level 2. These relations can in turn be investigated with different theoretical approaches (e.g., social constructivism in Level 2 and 3, phenomenology in Level 2 to 1), giving Popper's three worlds theory a function of meta-theory, the use of which is also relevant beyond the German-speaking world (see, for example, Kühne and Berr, 2021; Kühne et al., 2021c; Koegst, 2022; see Fig. 3).

Figure 3Karl Popper's three worlds theory and its derivations to three spaces and three landscapes. On the one hand, it becomes clear that space and landscape are not congruent, and landscape is a normatively and aesthetically charged special case of landscape; on the other hand, landscape (on Levels 2 and 3) has contents that are not spatially conceived but metaphorically, such as educational landscape. The three worlds (analogous to spaces and landscapes) are connected via World 2. World 2 can innovatively influence World 3, World 3 influences World 2 by means of socialization, and World 2 observes World 1 and is structured by it (in detail in Kühne and Berr, 2021; figure after Kühne, 2020).

The “open society” provides a normative framework today for society in general, science in particular, that is also of relevance outside of German-speaking areas. The central superiority of Popper is the indeterminacy of the future. If the future is not predetermined, then the task is to find the most suitable solutions possible to concrete challenges. This applies to society as a whole as well as to science in particular. Here, in particular, the problem of the moralization mentioned in the previous section becomes clear: moralizations inhibit the development of the potentials of the open society, since, first, they make the search for suitable solutions for concrete challenges more difficult; second, they make the recognition of concrete challenges more difficult (since the world is always constructed from a moral perspective); third, since moralizations are extended to fields of human coexistence that go beyond the original field of morality, there is a close coexistence of human beings (Grau, 2017; Müller-Salo, 2020; Stegemann, 2018; Sofsky, 2013, 2007a, b; Strenger, 2017). This moralization of the world is also by no means limited to the German-speaking world; it has international relevance.

At this point, the connection to Ralf Dahrendorf's life chance theory, later also conflict theory, becomes clear: moralization restricts life chances, as it is always connected to the generation of ligatures, where these do not serve to secure the existence of society but merely restrict options. The generation of ligatures restricting options thus means a reduction of contingency, which in turn is associated with the reduction of society. Options are excluded that might offer a more suitable way of dealing with current social challenges. The norm of maximizing life chances in society, as formulated by Dahrendorf, means not least taking a critical stance of transferring options into ligatures for the purpose of maintaining or expanding power of the privileged. This critical stance exists regardless of the nature and origin of privilege, whether from economic or political sources. The norm of expanding life chances in an open society, in turn, has implications for dealing with conflict. Since conflicts are structurally inherent in all societies, but these structural differences cannot be resolved – without giving up the potential for change in societies – it is necessary to find regulations for societal conflicts in order to release the productive potential of societies. This release, in turn, is constitutively linked to the open society, since it is here that contingent options for dealing with concrete problems are developed (Brunnhuber, 2019; Kühne et al., 2021c). The international relevance of Dahrendorf's conflict theory, as well as his discussions of civil society and European unification, is evident not least from his international reception (e.g., Bovone, 1982; Crouch, 2011; Saraceno, 1990).

However, Dahrendorf's conflict theory does not just have significance beyond the German-speaking area as a concretization of Karl Popper's open society: already the statement of the conflictual nature of every existing society points to its universalism. Also, the statement of the phased nature of social conflicts, as well as the idea of raising productive potentials of conflicts in the form of their regulation, can be understood as universal. The same applies to the problem of moralizing other conflict parties, their positions, and conflicts themselves.

As shown, Karl Popper's understanding of the open society and his three worlds theory as well as Ralf Dahrendorf's theory of life chances, especially in connection with his conflict theory, shows a high degree of topicality, which is not regionally limited to the German-speaking area. Using the examples on conflicts about space and landscape, we have also illustrated the relevance of the discussed four approaches for spatial research as well as for dealing with space- or landscape-related conflicts. (1) The three worlds theory, applied to space and landscape and in connection with the three described modes, is very well able to depict, analyze, and explain the complexity of the construct character of individually as well as socially perceived and evaluated landscape and to bring it to a scientific understanding. (2) The concept of the open society makes it possible to take up the diversity of interpretation and evaluation due to this complexity in its contingency without prejudice and to strive for open decisions in democratic negotiation processes on how to deal with disputed options of interpretation, evaluation, and handling. (3) The life chance concept in conjunction with the conceptual pair “options–ligatures” can demonstrate how the choice of specific interventions in landscapes can positively or negatively affect life chances, options, and ligatures. (4) The concept of conflict regulation makes it possible not only to regulate the unavoidable conflict potential of the multitude of possible interventions in landscapes in concrete cases by peaceful means but also ideally to steer them into socially productive paths.

The theoretical quadriga presented here combines different analytical approaches. These relate to the understanding of the phasing of conflicts, to the division of the of the world, space, and landscape into the levels of the social/cultural, the individual, as well as the material. However, they also combine procedural approaches, such as the development of appropriate responses to concrete social, political, or scientific challenges, as well as to the regulation of conflict. It also provides a normative basis for the orientation of open societies to the principle of maximizing life chances. The theoretical quadriga presented here is also applicable in a variety of ways beyond the spatial and landscape conflicts presented in the examples on space conflicts, not least through the understanding of Karl Popper's three worlds theory as a metatheory advocated here, which allows for the possibility of integrating other theoretical approaches into the framework (see, for example, Chilla et al., 2015; Kühne, 2018b; Eckardt, 2014; Kühne and Jenal, 2021). The dual concept of ligatures and options with regard to the life chance concept can serve as an analytical tool for the complicated interactions between ligatures, freedoms, options, and life chances, which are often obscured and, as a result, unilaterally resolved. Even if they may be seen through, there remains the danger of instrumentalizing or strategically advocating specific ligatures or favoring options or freedoms that are meaningless in terms of ties. The theoretical quadriga presented here can also be understood as an alternative to the “critical” and “poststructuralist” mainstream. Especially the meta-theoretical framework of Karl Popper's three worlds theory offers a theoretical and methodological openness that facilitates the search for suitable theoretical and empirical approaches to Worlds 1, 2, and 3 and also enables the integration of critical and poststructuralist theories, at least to the extent that they do not represent an exclusivist deterministic–teleological understanding of the world. Popper and Dahrendorf have each, within the framework of their theories, repeatedly pointed to the incompleteness and openness of human knowledge as well as to the non-determinacy and thus incompleteness and openness of social, individual, and political developments. This critique of a “historicism” turns against any form of determinism or historical teleology as well as against forms of critique that conceive themselves as no longer in need of critique and ultimately as absolute, which immunizes the latter against any critique of itself.

Both thinkers, Karl Popper and Ralf Dahrendorf are situated in the tradition of the Enlightenment, they are advocates of individual freedom and responsibility. In this respect, they are hardly compatible with the poststructuralist and neo-Marxist mainstream of German-speaking geography. Norms are not formulated by them in the form of moral ligatures, but in the form of ethical ligatures, enabling individual life chances. Moreover, their focus is on enabling and integration, not on discursive rejection and paternalization. Thereby, this approach certainly has potentials for scholars who do not want to subordinate the world into the template of their own world view but – following Popper's critical rationalism – pursue the testing of theories through empirical research. This in turn is connected with another form of criticism, self-criticism. Which also reflects on one's own changing role in a changing world and does not grant one's own position that of a superior judge.

Especially in a time when, especially in university contexts, the struggle for the more suitable argument with people who represent a different world view is replaced by the fact that those who think differently are banned from the discourse, it is highly topical to deal with the thoughts of Popper and Dahrendorf on an open society and open science. If this openness is lost, society will lose not only its liberty but also its ability to adapt to current and future challenges.

No data sets were used in this article.

The conceptualization of the work was done by OK, LL, and KB, as well as the development and implementation of the methodology and the validation. Writing (preparation of the initial draft) was also done jointly by the three authors. The visualization, project management, and writing (review and editing) were done by OK.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank the reviewers for their valuable comments.

This paper was edited by Nadine Marquardt and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Ackermann, U.: Das Schweigen der Mitte: Wege aus der Polarisierungsfalle, WBG, Darmstadt, 206 pp., ISBN 978-3806240573, 2020.

Becker, S. and Naumann, M.: Energiekonflikte erkennen und nutzen, in: Bausteine der Energiewende, edited by: Kühne, O. and Weber, F., Springer VS, Wiesbaden, 509–522, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-19509-0_1, 2018.

Berlin, I.: Freiheit: Vier Versuche, Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt (Main), 332 pp., ISBN 10:3100052072, 1995 [1969].

Bovone, L.: Libertà e utopia in Marcuse e Dahrendorf, Studi di Sociologia, 20, 273–296, 1982.

Boyer, A.: Introduction à la lecture de Karl Popper, Éditions Rue d'Ulm, Paris, ISBN 9782728833023, https://doi.org/10.14375/NP.9782728836918, 2017 [1994].

Brunnhuber, S.: Die offene Gesellschaft: Ein Plädoyer für Freiheit und Ordnung im 21. Jahrhundert, oecom, München, ISBN 978-3-96238-105-9, 2019.

Cavalli, L.: Sociologie del nostro tempo, il Mulino, Bologna, 1973.

Chilla, T., Kühne, O., Weber, F., and Weber, F.: “Neopragmatische” Argumente zur Vereinbarkeit von konzeptioneller Diskussion und Praxis der Regionalentwicklung, in: Bausteine der Regionalentwicklung, edited by: Kühne, O. and Weber, F., Springer VS, Wiesbaden, 13–24, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-02881-7_2, 2015.

Corchia, L.: Dahrendorf e Habermas: Un sodalizio intellettuale, SocietàMutamentoPolitica, 10, https://www.torrossa.com/gs/resourceproxy?an=4527391&publisher=ff3888#page=142 (last access: 17 May 2022), 2019.

Corvi, R.: An introduction to the thought of Karl Popper, Routledge, London, New York, 224 pp., ISBN 9781134793693, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203982570, 2005 [1997].

Crouch, C.: Ralf Gustav Dahrendorf 1929–2009, Proc. Brit. Acad., 172, 93–111, 2011.

Dahrendorf, R.: Marx in Perspektive: Die Idee des Gerechten im Denken von Karl Marx, Dietz, Hannover, 1952.

Dahrendorf, R.: Soziale Klassen und Klassenkonflikt in der industriellen Gesellschaft, Enke, Stuttgart, 1957.

Dahrendorf, R.: Homo Sociologicus: Ein Versuch zur Geschichte, Bedeutung und Kritik der Kategorie der sozialen Rolle, Westdeutscher Verlag, Köln, Opladen, 1959.

Dahrendorf, R.: Gesellschaft und Freiheit: Zur soziologischen Analyse der Gegenwart, Piper, München, 1961.

Dahrendorf, R.: Pfade aus Utopia: Arbeiten zur Theorie und Methode der Soziologie, Piper, München, ISBN 978-3492101011, 1968.

Dahrendorf, R.: Aktive und passive Öffentlichkeit: Über Teilnahme und Initiative im politischen Prozeß moderner Gesellschaften, in: Das Publikum, edited by: Löffler, M., C. H. Beck, München, 1–12, 1969.

Dahrendorf, R.: Konflikt und Freiheit: Auf dem Weg zur Dienstklassengesellschaft, Piper, München, 336 pp., ISBN 978-3492017824, 1972.

Dahrendorf, R.: Lebenschancen: Anläufe zur sozialen und politischen Theorie, Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch, 559, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt (Main), 239 pp., ISBN 3518370596, 1979.

Dahrendorf, R.: Il conflitto sociale nella modernità: Saggio sulla politica della modernità, Sagittari Laterza, Laterza, Roma-Bari, 253 pp., ISBN 9788842034407, 1989.

Dahrendorf, R.: Per un nuovo liberalismo, Laterza, Roma-Bari, 1988.

Dahrendorf, R.: Soziale Klassen und Klassenkonflikt: Zur Entwicklung und Wirkung eines Theoriestücks, Zeitschrift für Soziologie, XIV, 236–240, 1985.

Dahrendorf, R.: La libertà che cambia, Laterza, Roma-Bari, ISBN 9788842044635, 1981.

Dahrendorf, R.: Die neue Freiheit: Überleben und Gerechtigkeit in einer veränderten Welt, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt (Main), p. 126, ISBN 3-518-37123-1, 1980.

Dahrendorf, R.: Liberalism, in: The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, edited by: Eatwell, J., Macmillan, London, 385–389, 1991.

Dahrendorf, R.: Der moderne soziale Konflikt: Essay zur Politik der Freiheit, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt DVA, Stuttgart, p. 326, ISBN 3-421-06539-X, 1992.

Dahrendorf, R.: Der moderne soziale Konflikt: Essay zur Politik der Freiheit, dtv, München, p. 325, ISBN 3-423-04628-7, 1994.

Dahrendorf, R.: Europäisches Tagebuch, Steidl, Göttingen, p. 176, ISBN 3-88243-370-1, 1995.

Dahrendorf, R.: Über Grenzen: Lebenserinnerungen, C. H. Beck, München, 189 pp., ISBN 3406493386, 2002.

Dahrendorf, R.: La società riaperta: Dal crollo del muro alla guerra in Iraq, Storia e società, Laterza, Roma, 414 pp., ISBN 978-8842074809, 2005.

Dahrendorf, R.: Versuchungen der Unfreiheit: Die Intellektuellen in Zeiten der Prüfung, C. H. Beck, München, 239 pp., ISBN 9783406540547, 2006.

Dahrendorf, R.: Freiheit – eine Definition, in: Welche Freiheit: Plädoyers für eine offene Gesellschaft, edited by: Ackermann, U., Matthes & Seitz, Berlin, 26–39, ISBN 9783882218855, 2007.

Dahrendorf, R.: Quadrare il cerchio ieri e oggi: Benessere economico, coesione sociale e libertà politica, GLF editori Laterza, Roma, 133 pp., ISBN 8842089273, 2009.

Dahrendorf, R.: The Modern Social Conflict: The Politics of Liberty, Routledge, Abingdon, Oxon, New York, 209 pp., https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315133195, 2017.

Diefenbach, H.: Die Theorie der Rationalen Wahl oder “Rational Choice” – Theorie (RCT), in: Soziologische Paradigmen nach Talcott Parsons: Eine Einführung, edited by: Brock, D., Diefenbach, H., Junge, M., Keller, R., and Villányi, D., VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden, 239–290, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-91454-1_5, 2009.

Dobson, A.: Green Political Thought, in: 4th Edn., Routledge, London, New York, 225 pp., https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203964620, 2007.

Eckardt, F.: Stadtforschung: Gegenstand und Methoden, Springer VS, Wiesbaden, 2443 pp., https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-00824-6, 2014.

Eichenauer, E., Reusswig, F., Meyer-Ohlendorf, L., and Lass, W.: Bürgerinitiativen gegen Windkraftanlagen und der Aufschwung rechtspopulistischer Bewegungen, in: Bausteine der Energiewende, edited by: Kühne, O. and Weber, F., Springer VS, Wiesbaden, 633–651, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-19509-0_32, 2018.

Ferrarotti, F.: Introduzione, in: Homo sociologicus, edited by: Dahrendorf, R., Armando, Roma, 7–26, ISBN 978-8860816191, 2010.

Flaßpöhler, S.: Sensibel: Über moderne Empfindlichkeit und die Grenzen des Zumutbaren, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart, ISBN 978-3608983357, 2021.

Fraser, N. and Honneth, A.: Redistribution or recognition?: A political-philosophical exchange, Verso, London, Paris, 276 pp., ISBN 9781859844922, 2003.

Gailing, L. and Leibenath, M.: Political landscapes between manifestations and democracy, identities and power, Landsc. Rese., 42, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2017.1290225, 2017.

Giddens, A.: Central Problems in Social Theory: Action, structure and contradiction in social analysis, 1979 Auflage, Contemporary social theory, Macmillan Education, IX, 304 Seiten in 1 Teil, Palgrave, Oxford, ISBN 9780333272947, 1979.

Grau, A.: Hypermoral: Die neue Lust an der Empörung, 2. Auflage, Claudius, München, 128 pp., ISBN 9783532628034, 2017.

Grau, A.: Säkularisierung und Selbsterlösung: Die identitätslinke Läuterungsagenda als Religionsderivat, in: Identitätslinke Läuterungsagenda: Eine Debatte zu ihren Folgen für Migrationsgesellschaften, edited by: Kostner, S., Ibidem-Verlag, Stuttgart, 143–150, ISBN 978-3838213071, 2019.

Greener, I.: Agency, social theory and social policy, Crit. Social Policy, 22, 300–337, https://doi.org/10.1177/02610183020220040701, 2002.

Gryl, I.: Spaces, Landscapes and Games: the Case of (Geography) Education using the Example of Spatial Citizenship and Education for Innovativeness, in: The Social Construction of Landscapes in Games, edited by: Edler, D., Kühne, O., and Jenal, C., Springer, Wiesbaden, 359–376, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-35403-9_21, 2022.

Hard, G.: Über Räume reden: Zum Gebrauch des Wortes “Raum” in sozialwissenschaftlichem Zusammenhang, in: Landschaft und Raum: Aufsätze zur Theorie der Geographie, edited by: Hard, G., Universitätsverlag Rasch, Osnabrück, 235–252, ISBN 9783935326377, 2002.

Jackson, J. B.: Discovering the Vernacular Landscape, Yale University Press, New Haven, 165 pp., ISBN 0-300-03138-6, 1984.

Jenal, C., Endreß, S., Kühne, O., and Zylka, C.: Technological Transformation Processes and Resistance – On the Conflict Potential of 5G Using the Example of 5G Network Expansion in Germany, Sustainability, 13, 1–21, https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413550, 2021.

Kamlage, J.-H., Drewing, E., Reinermann, J. L., de Vries, N., and Flores, M.: Fighting fruitfully? Participation and conflict in the context of electricity grid extension in Germany, Utilities Policy, 64, 101022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jup.2020.101022, 2020.

Kocka, J.: Dahrendorf in Perspektive, Soziologische Revue, 27, 151–158, 2004.

Koegst, L.: Potentials of Digitally Guided Excursions at Universities Illustrated Using the Example of an Urban Geography Excursion in Stuttgart, KN – Journal of Cartography and Geographic Information, 72, 59–71, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42489-022-00097-4, 2022.

Korf, B.: Schwierigkeiten mit der kritischen Geographie, Geogr. Helv., 74, 193–204, https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-74-193-2019, 2019.

Korf, B.: `German Theory': On Cosmopolitan geographies, counterfactual intellectual histories and the (non)travel of a `German Foucault', Environ. Plan. D, 39, 026377582198969, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775821989697, 2021.

Kostner, S.: Identitätslinke Läuterungsagenda: Welche Folgen hat sie für Migrationsgesellschaften?, in: Identitätslinke Läuterungsagenda: Eine Debatte zu ihren Folgen für Migrationsgesellschaften, edited by: Kostner, S., Ibidem-Verlag, Stuttgart, 17–74, ISBN 978-3838213071, 2019.

Kühne, O.: Landschaft und Wandel: Zur Veränderlichkeit von Wahrnehmungen, XI, Springer VS, Wiesbaden, I–XI, 1–92, ISBN 978-3-658-18533-6, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-18534-3, 2018a.

Kühne, O.: Reboot “Regionale Geographie” – Ansätze einer neopragmatischen Rekonfiguration “horizontaler Geographien”, Bericht. Geogr. Landesk., 92, 101–121, 2018b.

Kühne, O.: Dahrendorf as champion of a liberal society – border crossings between political practice and sociopolitical theory, Società Mutamento Politica, 10, 37–50, 2019.

Kühne, O.: Landscape Conflicts: A Theoretical Approach Based on the Three Worlds Theory of Karl Popper and the Conflict Theory of Ralf Dahrendorf, Illustrated by the Example of the Energy System Transformation in Germany, Sustainability, 12, 1–20, https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176772, 2020.

Kühne, O.: Foodscapes – a Neopragmatic Redescription, Bericht. Geogr. Landesk., 96, 5–25, https://doi.org/10.25162/bgl-2022-0016, 2022.

Kühne, O. and Berr, K.: Wissenschaft, Raum, Gesellschaft: Eine Einführung zur sozialen Erzeugung von Wissen, Springer VS, Wiesbaden, 2021.

Kühne, O. and Jenal, C.: The Threefold – Landscape Dynamics – Basic Considerations, Conflicts and Potentials of Virtual Landscape Research, in: Modern Approaches to the Visualization of Landscapes, edited by: Edler, D., Jenal, C., and Kühne, O., Springer VS, Wiesbaden, 389–402, ISBN 978-3-658-30955-8, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-30956-5, 2020.

Kühne, O. and Jenal, C.: Baton Rouge – A Neopragmatic Regional Geographic Approach, Urban Sci., 5, 1–17, https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci5010017, 2021.

Kühne, O. and Leonardi, L.: Ralf Dahrendorf: Between Social Theory and Political Practice, Palgrave Macmillan, London, ISBN 978-3-030-44296-5, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44297-2, 2020.

Kühne, O. and Weber, F.: Conflicts and negotiation processes in the course of power grid extension in Germany, Landsc. Res., 43, 529–541, https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2017.1300639, 2018.

Kühne, O., Edler, D., and Jenal, C.: A Multi-Perspective View on Immersive Virtual Environments (IVEs), ISPRS – Int. J. Geo-Inf., 10, 1–22, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10080518, 2021a.

Kühne, O., Koegst, L., Zimmer, M.-L., and Schäffauer, G.: “… Inconceivable, Unrealistic and Inhumane”: Internet Communication on the Flood Disaster in West Germany of July 2021 between Conspiracy Theories and Moralization – A Neopragmatic Explorative Study, Sustainability, 13, 1–23, https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011427, 2021b.

Kühne, O., Berr, K., Jenal, C., and Schuster, K.: Liberty and Landscape: In Search of Life-chances with Ralf Dahrendorf, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, ISBN 978-3-030-84325-0, 2021c.

Kühne, O., Berr, K., and Jenal, C.: Die geschlossene Gesellschaft und ihre Ligaturen: Eine Kritik am Beispiel `Landschaft', Springer VS, Wiesbaden, ISBN 978-3-658-38582-8, 2022.

Lefèbvre, H.: La production de l'espace, L'Homme et la société, 31–32, 15–32, 1974.

Leibenath, M. and Otto, A.: Competing Wind Energy Discourses, Contested Landscapes, Landscape Online, 8, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.3097/LO.201438, 2014.

Leonardi, L.: Introduzione a Dahrendorf, Maestri del Novecento, 20, VII, Editori Laterza, Roma, Bari, I–VII, 1–177, ISBN 8858110218, 2014.

Leonardi, L.: Ipotesi di quadratura del cerchio: Diseguaglianze, chances di vita e politica sociale in Ralf Dahrendorf, Società Mutamento Politica, 10, 127–139, 2019.

Leonardi, L.: Dahrendorf, Habermas, Giddens e il dibattito sulla “Terza via”. La diagnosi del mutamento e il controverso rapporto tra teoria e prassi, Quaderni di Teoria Sociale, 567–622, https://flore.unifi.it/handle/2158/1189683 (last access: 21 July 2023), 2020.

Mackert, J. (Ed.): Die Theorie sozialer Schließung, VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden, ISBN 978-3-8100-3970-5, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-663-07912-5, 2004.

Mackert, J.: Opportunitätsstrukturen und Lebenschancen, Berlin. J. Soziol., 20, 401–420, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11609-010-0135-7, 2010.

Matys, T. and Brüsemeister, T.: Gesellschaftliche Universalien versus bürgerliche Freiheit des Einzelnen – Macht, Herrschaft und Konflikt bei Ralf Dahrendorf, in: Macht und Herrschaft: Sozialwissenschaftliche Theorien und Konzeptionen, 2. aktualisierte und erweiterte Auflage, edited by: Imbusch, P., Springer VS, Wiesbaden, 195–216, ISBN 978-3-531-17924-7, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-93469-3, 2012.

Meifort, F.: Ralf Dahrendorf: Eine Biographie, C. H. Beck, München, ISBN 978-3-406-71397-2, 2017.

Meifort, F.: The Border Crosser: Ralf Dahrendorf as a Public Intellectual between Theory and Practice, Società Mutamento Politica, 10, 67–77, 2019.

Merton, R. K.: Opportunity structure: The emergence, diffusion, and differentiation of a sociological concept, 1930s–1950s, in: The legacy of anomie theory, edited by: Adler, F., Laufer, W. S., and Merton, R. K., Transaction Publishers, New Brunswick, 3–78, ISBN 1-000-67579-3, 1995.

Mori, L.: Chance: Max Weber e la filosofia politica, Edizioni ETS, Pisa, 198 pp., ISBN 9788846747198, 2016.

Müller-Salo, J.: Klima, Sprache und Moral: Eine philosophische Kritik, Philipp Reclam jun., Ditzingen, ISBN 9783150140406, 2020.

Munro, L.: Life chances, education and social movements, Anthem Press, London, New York, 251 pp., ISBN 9781783089956, 2019.

Niedenzu, H.-J.: Konflikttheorie: Ralf Dahrendorf, in: Soziologische Theorie: Abriß ihrer Hauptvertreter, 7. Auflage, edited by: Morel, J., Bauer, E., Maleghy, T., Niedenzu, H.-J., Preglau, M., and Staubmann, H., R. Oldenbourg Verlag, München, Wien, 171–189, ISBN 3486255797, 2001.

Niemann, H.-J.: Karl Poppers Spätwerk und seine `Welt 3', in: Handbuch Karl Popper, Living reference work, edited by: Franco, G., Springer Reference Geisteswissenschaften, Wiesbaden, 1–18, ISBN 978-3-658-16238-2, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-16242-9, 2019.

Paris, R.: Normale Macht: Soziologische Essays, UVK Verlagsgesellschaft, Konstanz, 239 pp., ISBN 9783896695178, 2005.

Poggiolini, I.: Le tre Europe di Ralf Dahrendorf, Società Mutamento Politica, 10, 91–99, 2019.

Popper, K. R.: Objektive Erkenntnis: Ein evolutionärer Entwurf, Hoffmann und Campe, Hamburg, 417 pp., ISBN 3-455-09088-5, 1973.

Popper, K. R.: Three Worlds: Tanner Lecture, Michigan, April 7, 1978, Michigan Quarterly Review, 141–167, https://tannerlectures.utah.edu/_documents/a-to-z/p/popper80.pdf (last access: 21 July 2023), 1979.

Popper, K. R.: Logik der Forschung, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, 481 pp., ISBN 3161478371, 1989.

Popper, K. R.: Die offene Gesellschaft und ihre Feinde: Falsche Propheten – Hegel Marx und die Folgen, in: 7th Edn., 2, J. C. B. Mohr, Tübingen, ISBN 3825217256, 1992.

Popper, K. R.: The Open Society and Its Enemies, Routledge, Abingdon, 1372 pp., ISBN 9780415610216, 2011 [1947].

Popper, K. R.: Alle Menschen sind Philosophen, Herausgegeben von Heidi Bohnet und Klaus Stadler, Piper, München, 281 pp., ISBN 978-3-492-24189-2, 2018 [1984].

Popper, K. R.: Auf der Suche nach einer besseren Welt: Vorträge und Aufsätze aus dreißig Jahren, Piper, München, 282 pp., ISBN 9783492206990, 2019 [1987].

Popper, K. R. and Eccles, J. C.: Das Ich und sein Gehirn, Piper, München, 699 pp., ISBN 3-492-02447-5, 1977.

Saraceno, C.: Davvero non possiamo non dirci dahrendorfiani?, Stato e Mercato, 282–288, 1990.

Schafranek, M., Huber, F., and Werndl, C.: Die evolutionäre Grundlage Poppers Drei-Welten-Lehre: Eine unberücksichtigte Perspektive in der human-ökologischen Theoriendiskussion der Geographie, 94, 129–142, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27819084?casa_token=bsa1rjnquh (last access: 24 July 2023), 2006.

Schultz, H.-D.: Deutsches Land – deutsches Volk: Die Nation als geographisches Konstrukt, Berichte zur deutschen Landeskunde, 72, 85–114, 1998.

Schütz, A.: Gesammelte Aufsätze 1: Das Problem der Wirklichkeit, Martinus Nijhoff, Den Haag, ISBN 978-9024751167, 1971 [1962].

Schütz, A.: Der sinnhafte Aufbau der sozialen Welt: Eine Einleitung in die verstehende Soziologie, UVK Verlagsgesellschaft, Konstanz, ISBN 978-3896697486, 2004 [1932].

Schütz, A. and Luckmann, T.: Strukturen der Lebenswelt, UTB, Konstanz, ISBN 978-3825224127, 2003 [1975].

Sen, A.: La disuguaglianza: Un riesame critico, Biblioteca paperbacks, il Mulino, Bologna, 300 pp., 1994.

Sofsky, W.: Das Prinzip Freiheit, in: Welche Freiheit: Plädoyers für eine offene Gesellschaft, edited by: Ackermann, U., Matthes & Seitz, Berlin, 40–61, ISBN 9783882218855, 2007a.

Sofsky, W.: Verteidigung des Privaten: Eine Streitschrift, Beck, München, p. 158, ISBN 9783406562983, 2007b.

Sofsky, W.: Das “eigentliche Element”: Über das Böse, Kursbuch 176: Ist Moral gut?, Murmann, Hamburg, 16 pp., ISBN 9783867743181, 2013.

Stegemann, B.: Die Moralfalle: Für eine Befreiung linker Politik, Matthes & Seitz, Berlin, 115 pp., ISBN 9783957577481, 2018.

Strasser, H. and Nollmann, G.: Ralf Dahrendorf: Grenzgänger zwischen Wissenschaft und Politik, Soziologie heute, 3, 32–35, 2010.

Strenger, C.: Abenteuer Freiheit: Ein Wegweiser für unsichere Zeiten, Edition Suhrkamp Sonderdruck, Suhrkamp, Berlin, 122 pp., ISBN 9783518745229, 2017.

Strohschneider, P.: Zumutungen: Wissenschaft in Zeiten von Populismus, Moralisierung und Szientokratie, kursbuch.edition, Hamburg, ISBN 9783961961542, 2020.

Weber, F., Jenal, C., Roßmeier, A., and Kühne, O.: Conflicts around Germany's Energiewende: Discourse patterns of citizens' initiatives, Quaestiones Geographicae, 36, 117–130, https://doi.org/10.1515/quageo-2017-0040, 2017.

Weber, F., Kühne, O., Jenal, C., Aschenbrand, E., and Artuković, A.: Sand im Getriebe: Aushandlungsprozesse um die Gewinnung mineralischer Rohstoffe aus konflikttheoretischer Perspektive nach Ralf Dahrendorf, Springer VS, Wiesbaden, ISBN 9783658215255, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-21526-2, 2018.

Weichhart, P.: How Does the Person Fit into the Human Ecological Triangle? From dualism to duality: the transactional worldview, in: Human Ecology: Fragments of Anti-Fragmentary Views of the World, edited by: Steiner, D. and Nauser, M., Routledge, London, 103–124, ISBN 9780203414989, 1993.

Weichhart, P.: Die Räume zwischen den Welten und die Welt der Räume, in: Handlungszentrierte Sozialgeographie: Benno Werlens Entwurf in kritischer Diskussion, edited by: Meusburger, P., Steiner, Stuttgart, 67–94, ISBN 3515076131, 1999.

Werlen, B.: Thesen zur handlungstheoretischen Neuorientierung sozialgeographischer Forschung, Geogr. Helv., 41, 67–76, https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-41-67-1986, 1986.

Werlen, B.: Gesellschaft, Handlung und Raum: Grundlagen handlungstheoretischer Sozialgeographie, Erdkundliches Wissen, X, 89, Steiner, Stuttgart, p. 315, ISBN 3515048863, 1997.

Zierhofer, W.: Geographie der Hybriden, Erdkunde, 53, 1–13, 1999.

Zierhofer, W.: Gesellschaft: Transformation eines Problems, Wahrnehmungsgeographische Studien, 20, edited by: Hasse, J. and Krüger, R., Bibliotheks- und Informationssystem der Univ, Oldenburg, Oldenbrug, 299 pp., ISBN 381420803X, 2002.

Zimmer, R.: Karl Poppers “Die offene Gesellschaft und ihre Feinde”, in: Handbuch Karl Popper, Living reference work, edited by: Franco, G., Springer Reference Geisteswissenschaften, Wiesbaden, 65–80, ISBN 9783658162382, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-16239-9_4, 2019.

Zimmer, R. and Morgenstern, M.: Karl R. Popper: Eine Einführung in Leben und Werk, 2. durchgesehene und ergänzte Auflage, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, ISBN 3161535766, 2015.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- The Open Society and its Enemies – the principles of anti-totalitarian thought by Popper and Dahrendorf

- Popper's three worlds theory as an analytical framework for spatial research

- Dahrendorf's concept of “life chances” as an operationalization of the “open society”

- Conflicts of space and conflicts of interpretation of space – interpreted with Popper and Dahrendorf

- The international relevance of Popper and Dahrendorf

- Conclusion

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- The Open Society and its Enemies – the principles of anti-totalitarian thought by Popper and Dahrendorf

- Popper's three worlds theory as an analytical framework for spatial research

- Dahrendorf's concept of “life chances” as an operationalization of the “open society”

- Conflicts of space and conflicts of interpretation of space – interpreted with Popper and Dahrendorf

- The international relevance of Popper and Dahrendorf

- Conclusion

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References