the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Arrival brokers as a key component of the arrival infrastructure: how established migrants support newcomers

Nils Hans

In recent years, numerous studies have stressed the importance of established migrants helping newcomers access settlement information. This article focuses on the everyday practices of these so-called “arrival brokers” in supporting newcomers in their initial arrival process. The analysis combines the theoretical strands on “arrival infrastructures”, arrival brokers, and the concept of solidarity. The qualitative empirical research in an arrival neighbourhood in the German city of Dortmund shows that arrival brokers support newcomers by sharing arrival-specific knowledge and by structuring the arrival infrastructure network. These practices can be attributed to a situational place-based solidarity. The article shows that using the infrastructure perspective for analysing migrants' brokering practices helps us understand the transformative power wielded by migrants themselves in making, shaping, and maintaining arrival support structures.

- Article

(368 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

I left my number in an Afghan grocery store. When Afghans go there and ask for help, the shopkeeper gives them my number. If they need help, they can just call. (Milad, 20, Afghanistan, personal communication, 2021)

An Afghan refugee, 20-year-old Milad (all persons interviewed in this study were given pseudonyms by the author), arrived in Dortmund 3 years ago, where he was supported by an advisory organisation for refugees. He now works there as a volunteer. In his free time, he contacts immigrants in need of help, building on the experience he has collected so far. The example of Milad shows that there are “informal” support structures in arrival neighbourhoods accessible for newcomers in need of support or experiencing difficulties in “navigating the system”.

In recent years, a number of studies have emerged on the role of established migrants in providing access to settlement information (Bakewell et al., 2012; Wessendorf, 2018; Phillimore et al., 2018). These studies reveal that “arrival brokers” (Hanhörster and Wessendorf, 2020) can play an important role in the arrival process of immigrants, providing them with support, for example in dealing with public authorities, and sharing arrival-specific knowledge such as local information on affordable housing or job vacancies. These studies emphasise the significance of informal networks as a way for migrants to share information and receive help.1

Such brokering practices are predominantly observed in arrival neighbourhoods, highly dynamic spaces characterised by immigration, fluctuating populations, and a concentration of arrival-specific infrastructures (Saunders, 2011; Hanhörster and Wessendorf, 2020). More often than not, such neighbourhoods are highly diverse, both socially and ethnically. The ongoing influx of migrants into already highly diversified spaces results in “new complexities [that] are `layered' on top of and positioned with regard to pre-existing patterns of diversity” (Vertovec, 2015:2). Various studies point to growing challenges related to increasing migration-driven social and ethnic diversity. For example, concerns have been raised about the ability of state service providers to respond to the welfare needs of a diversifying and ever-changing population (Phillimore, 2015). Closely linked to the debate on arrival neighbourhoods and super-diverse contexts is the concept of “arrival infrastructures” (Meeus et al., 2019). This concept shifts the focus to infrastructural opportunities providing access to arrival-specific resources, taking both institutional infrastructures and informal practices into account.

To date, little is known about these informal practices and the role played by individuals in providing information and resources. This calls for more nuanced empirical research on the phenomenon of arrival brokering in super-diverse contexts, i.e. research analysing the forms and extent of these practices, as well as individuals' motives for their behaviour. Focusing on established migrants in an arrival neighbourhood in Dortmund (Germany) who act as arrival brokers by providing arrival-specific knowledge and support, this study analyses their agency from an arrival infrastructure perspective, seeking to answer the following questions:

-

Where and how (among which groups of people and in which situations) does an exchange of arrival-specific knowledge between established and more recent immigrants take place?

-

What motivates arrival brokers to share their knowledge and what is the role of place in such processes?

-

How do arrival brokers support the initial arrival process of newcomers?

The term “arrival” is understood in this study as the process of accessing various functional, social, and symbolic resources to make progress in various societal sectors and navigate the system. This process can be longer or shorter (e.g. depending on one's own networks or residence status).

The article is structured as follows. Section 2 pulls together the theoretical strands on arrival infrastructures, arrival brokering, and the concept of solidarity. Section 3 presents the case study area and the research design, while Sect. 4 highlights the empirical findings on the extent of informal arrival brokering practices and motivations. Section 5 analyses the extent to which arrival brokers support the arrival process of newcomers in the initial arrival period, referring to debates on integration and taking account of the role of place for these processes. In the conclusion (Sect. 6), the political dimension of this study is discussed and recommendations for further research are formulated.

2.1 Arrival infrastructures and arrival brokering

Numerous studies have investigated migrants' arrival processes in a new place, with many of them conceptualising “arrival” under the term integration. Although the term is contested and widely criticised (for an overview, see Phillimore, 2020; Spencer and Charsley, 2021), it can be useful as an analytical concept as it focuses on the process of accessing resources and making progress in various societal sectors such as employment, housing, education, and health (Ager and Strang, 2008). While “integration” can be related to all societal groups, “arrival” focuses specifically on newcomers. The “turn to arrival” (Wilson, 2022:3459) therefore shifts the focus to the initial period of arriving in a new place and the related challenges of accessing resources that help one gain a foothold in the new surroundings. It is important to note that although the concept focuses on the initial period, arrival – as in most integration concepts – is not understood as a state to be achieved but as a permanent process. The “arrival lens” helps us better understand the relevance of place, i.e. of certain arrival spaces, and the infrastructures available there.

An emerging body of literature is looking at the relevance of place and the role of local differences in arrival opportunities (Robinson, 2010; Platts-Fowler and Robinson, 2015; Phillimore, 2020). Although research has demonstrated that new media and virtual networks play an important role for newcomers (Schrooten, 2012; Dekker and Engbersen, 2014; Udwan et al., 2020), the above-mentioned studies show that the local context continues to be of particular relevance for forming social relationships and for immigrants' access to support.

One dominant feature influencing arrival opportunities are arrival infrastructures. Research suggests that these can contribute significantly to migrants' access to resources in the initial arrival period (Meeus et al., 2019, 2020; Wessendorf, 2022). The term refers to concentrations of institutions, organisations, and players, facilitating arrival by providing arrival-specific information. These include formal support structures provided by the state, e.g. language schools or public advisory organisations as well as infrastructures established by non-governmental stakeholders, such as (migrant) advisory organisations, which often emerge in response to state policies (Schrooten and Meeus, 2020:419). The term also points to informal infrastructures and local service providers such as cafés, restaurants, ethnic shops, and hairdressers (Schrooten and Meeus, 2020:415). These infrastructures not only support newcomers in maintaining their transnational lifestyles but also facilitate arrival by acting as information hubs and places of encounter2, thereby contributing to an exchange of resources (Hall et al., 2017; Wessendorf and Phillimore, 2019; Hans and Hanhörster, 2020). One of the most relevant contributions from an arrival infrastructure perspective is the consideration not only of the physical infrastructures facilitating arrival considered but also of the key role played by specific players or groups within these. In recent years, several studies have looked at the role of long-established migrants in providing access to settlement information. Terms used to describe their function include “migrant infrastructures” (Hall et al., 2017), “soft infrastructures” (Boost and Oosterlynck, 2019), and “infrastructures of super-diversity” (Blommaert, 2014) (for an overview, see Wessendorf, 2022). Emphasising their mediating role and with reference to the term “migrant brokers” (Lindquist et al., 2012), Hanhörster and Wessendorf (2020) refer to these individuals and groups as “arrival brokers”, i.e. established (descendants of) immigrants with settlement experience who provide newcomers from various backgrounds with settlement information based on their arrival-specific knowledge (Phillimore et al., 2018; Wessendorf, 2018). Often acting within physically accessible locations such as shops, libraries, and (migrant) advisory organisations (Wessendorf, 2022), they support newcomers informally, helping them to bridge the “structural holes” (Burt, 1992) in the infrastructure network. Studies suggest that relationships with arrival brokers can be friendly in the sense that one main contact can enable pathways into societal systems (Bloch and McKay, 2015) or exploitative in the sense that the urgent needs of newcomers can be used to earn money (e.g. by pushing people into substandard housing) (Kohlbacher, 2020:133; Wessendorf, 2022:9).

As early as 2004, Abdoumaliq Simone extended the notion of infrastructure to the activities of people with the concept of “people as infrastructures” (Simone, 2004), describing how social infrastructures emerge (informally) through cooperation and the exchange of resources in improvised networks. These infrastructures are made up of people standing in where formal infrastructures are lacking, using their own agency to fill these gaps. While the concept does not understand these infrastructural practices as a selfless act but rather as an (economic) collaboration among residents pursuing their own advancement, little is known about what motivates arrival brokers in European cities to mediate and facilitate settlement information.

2.2 Motives behind brokering: solidarity in super-diverse contexts

People's motives for supporting others are manifold. One main motive discussed in the literature is solidarity. Widely used in the social sciences, the concept of solidarity has received considerable attention in recent migration research. However, there is no consistent definition of the concept in migration studies, as it is multidimensional and complex (for an overview, see Bauder and Juffs, 2020). In general, solidarity is described as “[t]he ties (e.g. kinship, religion) that bind people together in a group or society and their sense of connection to each other” (Bell, 2014). In this article, the focus is on solidarity between people with a migration history who live together in highly diversified social spaces and who support each other by sharing settlement information – and on the ties that bind them together.

Robert D. Putnam (2007) argues that, with increasing ethnic diversity, collective identity, and with it social capital and solidarity, decreases. This derives from the assumption that social capital and solidarity are primarily based on shared norms and values. In today's literature, there is evidence that solidarity is not primarily a result of shared norms and values, as it can also be observed in super-diverse contexts where people socialised in different systems of norms and values live together (Bynner, 2019). In addition to shared norms and values, Oosterlynck et al. (2015:768f.) identify “encounter” as a further important source of solidarity, highlighting the role of place. They argue that in super-diverse and rapidly changing contexts where traditional social bonds (family, work) lose their importance, solidarity is grounded in everyday places and practices in neighbourhoods where people of different ethnic and cultural backgrounds meet. However, the literature also indicates that not all encounters lead to meaningful social interactions and that, depending on the settings and individual motives, encounters can have ambivalent effects (Valentine, 2008:330).

The concept of solidarity is closely linked to that of reciprocity, generally understood as “doing for others what they have done for you” (Plickert et al., 2007:406). Empirical findings suggest that reciprocity, i.e. the process of immigrants sharing their collected knowledge and experiences once they have become established, can also be found in a super-diverse context where people with different backgrounds, norms, and values come together (Phillimore et al., 2018:224; Schillebeeckx et al., 2019:149; Hans and Hanhörster, 2020:84). Oosterlynck et al. (2017) argue that the understanding of solidarities, generally based on the spatial limitations of supposedly culturally homogenous nations, should be complemented by a relational perspective on a small-scale level: “If we want to develop a deep understanding of how diversity interacts with solidarity, a more place-based and historicising methodological approach is needed” (Oosterlynck et al., 2017:3).

To better understand arrival-brokering practices in super-diverse neighbourhoods, this study uses an infrastructure perspective and the concept of solidarity to analyse the agency of these brokers and their motives for sharing their knowledge.

3.1 The arrival neighbourhood Dortmund–Nordstadt

Dortmund is a city in the west of Germany and part of the post-industrial Ruhr area. As a result of deindustrialisation from the 1960s onwards, the city's population declined. However, around 2010 it started increasing, fuelled by immigration. Today, the city has some 600 000 inhabitants.

The selected case study area is Dortmund's Nordstadt, a working-class district located directly north of the city centre. The densely populated area is today home to 60 000 people. Initially populated by coal miners and steelworkers mainly from rural areas, from the mid-20th century onwards immigrants from different backgrounds have moved into the area: first, so-called “guest workers” from southern Europe and Turkey, then EU migrants from eastern Europe (especially since the accessions in the 2000s), and recently refugees (especially from Syria) (City of Dortmund, 2019a:17).

Today, Nordstadt is characterised by a spatial concentration of migration and poverty: some 52 % of the population have a foreign nationality, while a further 21 % are people with a migration background but with a German passport (City of Dortmund, 2019a:28). The share of the population dependent on social security benefits (39.4 %; City of Dortmund, 2019b:119) is more than twice as high as the city average. The city administration is aware of the particular role of Nordstadt as an arrival neighbourhood, and there are various city-wide and neighbourhood-based strategies to support arrivals, including the 2016 “New Immigration Strategy” which regulates cooperation between formal governmental and non-governmental players to facilitate arrival processes. There is also an active network of civil society players and support infrastructures, with a recent study identifying more than 220 social projects, many of which are focused on supporting arrival and integration (Kurtenbach and Rosenberger, 2021:45). Besides these formal arrival-related infrastructures, a large number of small (migrant) shops and service providers offer products and services in different languages. While the involvement of non-governmental players (e.g. NGOs) in municipal measures is progressing comparatively well, immigrants themselves are not yet actively involved. The role played by arrival brokers is often ignored.

3.2 Methodology

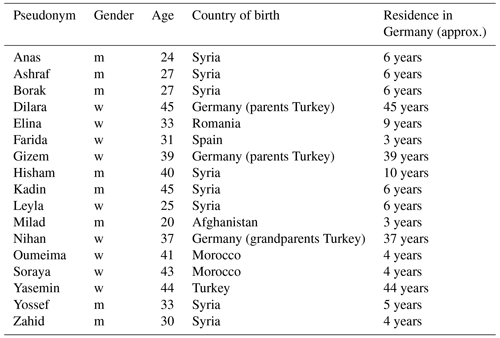

The study is based on 17 interviews with immigrants or their descendants living or working in Dortmund's Nordstadt. Made up of interview partners from most of the largest ethnic groups, the sample (see Table 1) broadly represents the socio-demographic composition of the people living in the area. While some of the interviewees arrived as refugees in recent years, others moved to Germany decades ago or were even born there. The study focuses on migrant arrivals in general rather than on refugee arrivals. There are several reasons for this: as described in the previous section, Nordstadt was and still is a destination for migrants from different countries of origin. While refugees account for a certain share of immigration to Dortmund, immigration from other EU countries was mostly even higher in recent years (City of Dortmund, 2019a:22). Depending on a migrant's residence status, access to and need for services vary. While in recent years many formal state-run arrival infrastructures (e.g. free language courses and so-called “integration courses”) have mainly targeted refugees with protection status and thus entitlement to stay, EU immigrants are more dependent on non-state-run services. Both therefore represent interesting target groups for studying arrival brokering.

The interviews were conducted with people characterised by the author as arrival brokers, i.e. people with a certain experience of settling in and living in Germany. Therefore, the sample was made up of adults living in Germany for at least 3 years (at the time the interview was conducted) and able to communicate in German. The condition for being considered an interview partner was that the person passes on their collected settlement knowledge in some form to other immigrants. The interviewees were mainly recruited via institutions located in Nordstadt, such as migrant organisations or advisory bodies. Accordingly, most of them currently work or have in the past worked (some on a voluntary basis) for organisations operating in the social field. However, the focus of the interviews was on their brokering activities outside this institutional context. Other interviewees had already been interviewed in previous project contexts. The author interviewed them again in relation to the new research focus. As the interviews were conducted in German, the sample did not include people who spoke no German but who nevertheless brokered information in other languages.

Interviewees were asked about their concrete informal brokering activities, especially in supporting newcomers and sharing their personal arrival-specific knowledge. The semi-structured interviews contained open questions on concrete examples of such knowledge transfer, i.e. where and in which situations it took place and what kinds of support were provided. To identify their potential willingness to support others, the interviewees were explicitly asked about situations in which a concrete transfer took place, focusing on their interaction with people not belonging to their primary networks (family and friends). To gain information about how these (sometimes fleeting) relationships between brokers and support recipients were structured, the questions focused on who these recipients were (e.g. in which socio-cultural aspects similarities or differences were seen), how the contact arose, and how (e.g. in which language) communication took place. To understand the motives of the arrival brokers, the questions were also on why they provided support and passed on their arrival-specific knowledge in their free time.

The interviews were conducted between June and December 2021 until the theoretical saturation point was reached (Glaser and Strauss, 1967). The empirical data were collected as part of a PhD project dealing with newcomers' access to resources in arrival neighbourhoods. All interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analysed by interpretative coding using the software MAXQDA.

The focus of this analysis is on the extent to which arrival brokers fulfil important functions in the arrival process of immigrants. The empirical findings thus point to the forms of support and knowledge transfer, as well as the relationships between arrival brokers and resource recipients, taking the motives for brokering into account.

4.1 Sharing arrival-specific knowledge: the role of arrival brokers

Overall, the interviews revealed that established migrants support newcomers in their settling-in process by sharing arrival-specific knowledge. All interviewees confirmed that they support or have supported new immigrants through sharing their own experiences. Most work (mainly as volunteers or for a few paid hours) in (migrant) advisory bodies where they help their clients (mostly immigrants) in an organised manner and with an institutional background. This formalised help mainly involves assistance with dealing with German authorities, such as translating documents, filling out forms, or arranging appointments.

In addition to this formal institutional support, all interviewees reported that, to a certain extent, they also supported other immigrants informally (see Lindquist, 2015; Tuckett, 2020). Besides the above-mentioned help with dealing with authorities, this informal support includes further assistance relating to the newcomers' everyday lives, such as accompanying them to authorities or doctors. This points to the fact that the capacities of the formal advisory services are often insufficient, meaning that employees are forced to provide assistance outside their working hours. In some cases, they also provide support in accessing important functional resources such as finding an affordable flat or a job: “People call me and say they are looking for a job. In most cases, I can either recommend something or ask a friend who then tells me that there is a vacancy in this or that company. Then I make the contact“ (Soraya, 43, Morocco, personal communication, 2021). This quote refers to the “linking social capital” (Woolcock, 2001) and the important mediation function of arrival brokers.

But how do people looking for support find the arrival brokers; how do resource providers and resource recipients get in touch with each other? Some interviewees reported that they got to know their clients in the advisory organisations where they work(ed) and that they gave them their private phone numbers in order to be able to support them more extensively outside this institutional context. In some cases, this would lead to a ripple effect: “I give people my number and they pass it on to others. I have no problem with that. At some point, a lot of people had my number and just called when they needed help” (Anas, 24, Syria, personal communication, 2021). Word soon spreads among newcomers about who has which information and contacts and who, above all, is willing to share this information even with strangers: “At some point I was quite well-known in Dortmund and people spoke to me on the streets in Nordstadt and asked if I could help them” (Hisham, 40, Syria, personal communication, 2021). This quote also refers to the relevance of “chance encounters” (Wessendorf and Phillimore, 2019:130), understood as unexpected encounters in public spaces that can lead to an exchange of relevant information, in this case by meeting a well-known arrival broker by chance on the street in Nordstadt. However, these quotes again point to the fact that many people are in need of help and that the capacities of formal advisory services are not sufficient or not sufficiently known. For this reason, arrival brokers donate their free time to support people in urgent need of help.

Cited at the beginning of the article, the story of Milad is an example of an arrival broker systematically offering support on his own. Having left his phone number in an Afghan grocery store frequented by immigrants (mainly Afghans), Milad uses this arrival-specific infrastructure to get in touch with people looking for help. This example also points to the important function of arrival infrastructures such as (ethnic) shops (Steigemann, 2019), libraries (Wessendorf, 2022), and religious spaces (Oduntan and Ruthven, 2021:91) as first points of reference for newcomers and to the brokering function of those working there.

The example of Milad suggests that the sharing of arrival-specific knowledge primarily takes place within ethnic boundaries, despite interviewees stating that they made no distinction between origins and would potentially help all people in need of support (see also Kohlbacher, 2020:132). This is due to the fact that newcomers in particular look for support in their mother tongue: “Most of them [the people he helps] come from Arab countries. Some speak Arabic, some also Kurdish. They have recently migrated to Germany, don't speak the language and need support” (Anas, 24, Syria, personal communication, 2021).

Another interesting aspect is that these relationships between resource providers and resource recipients are quite functional. Even though those concerned sometimes meet more than once, perhaps even with emotional support being provided (see Small, 2017), these meetings have a specific purpose and usually remain on a loose acquaintance footing. Wessendorf and Phillimore (2019:131) call these relationships “crucial acquaintances”, meaning that, while not usually turning into friendships, they can be crucial for the arrival process.

This also applies to online brokering practices, which similarly seem to play an important role in sharing information. Some interviewees reported that they were part of local WhatsApp or Facebook groups where immigrants came together and supported each other: “There are Facebook groups for every language or society, for example Arabic-speaking people. A lot of people ask questions there and you can just answer and offer your help” (Zahid, 30, Syria, personal communication, 2021). In these groups, people with similar linguistic-cultural backgrounds who now live together in one city communicate and exchange information (e.g. a WhatsApp group for Arabic women in Dortmund): “If someone needs help, she just writes in the group – `I need a job' or `I need the address of a doctor' – and then we are there. […] I have three groups, each with 150 to 200 Arabic women” (Soraya, 43, Morocco, personal communication, 2021). Two interesting aspects of this online brokerage are that most group members do not know each other personally and that this form of digital information sharing occurs alongside analogue forms of exchange. However, these virtual groups can be seen as online support infrastructures built by immigrants themselves where settlement information can be requested more or less anonymously and where a host of people share their accumulated arrival-specific knowledge (Dekker and Engbersen, 2014; Udwan et al., 2020).

Overall, the interviews revealed that people can play an important role as informal information nodes in the arrival infrastructure network and that they are an important complement to more formal support infrastructures – a feature which gained in prominence during the COVID-19 pandemic (Bynner et al., 2021; Thiery et al., 2021) when many support services (such as advisory organisations) had to close temporarily or were unable to provide face-to-face client contact due to the contact restrictions (Guadagno, 2020; Rebhun, 2021). The absence of these formal support infrastructures increased the need for informal support by arrival brokers: “During the COVID crisis, all the organisations were closed. That meant those in need of help had nowhere to go to fill out forms or have something translated. They therefore contacted people like me” (Yossef, 33, Syria, personal communication, 2021). The interviews indicated that arrival brokers, during the temporary closure of many infrastructures, were at least partially able to fill the gaps by providing last-minute help to newcomers.

4.2 Arrival brokers' motivation: situational place-based solidarity

These empirical findings raise the question of why arrival brokers share their own experiences that they themselves have collected with much effort and often with difficulties. The reasons are manifold. In Simone's (2004) study, people act primarily in their own interest, with the aim of getting ahead themselves. Studies researching exchange between immigrants have shown that “informal reciprocity” (Phillimore et al., 2018:224), in this sense understood as giving something back (to a new immigrant) for something that one received on one's own arrival, is a prominent reason for sharing arrival-specific knowledge (Phillimore et al., 2018; Schillebeeckx et al., 2019; Hans and Hanhörster, 2020), as corroborated by the interviews conducted in this study: “I received a lot of help when I arrived in Germany. And now I just want to give something back and pass on my experiences” (Yossef, 33, Syria, personal communication, 2021).

But the interviews also showed that not all people who now act as arrival brokers received something from others in their settling-in process, suggesting that it is more than just “giving something back”: “It is not important whether someone helped me or not. If I see people here who for example had to flee from a war and who now need help and support, then I help” (Anas, 24, Syria, personal communication, 2021). Therefore, it is a good idea to look at this collective support provided by migrants in a broader context. One aspect mentioned in nearly all answers to the question about motives was solidarity. But how can this solidarity be explained? To what can this kind of solidarity be ascribed? What are the ties binding people together in super-diverse contexts?

The literature on solidarity discusses “shared norms and values” as a key source of solidarity (Putnam, 2007; Oosterlynck et al., 2015). However, the interviews conducted in this study revealed that this was not the decisive reason for the interviewees' solidarity. Instead, it seemed to relate to the fact that they now found themselves in similar situations and had experienced similar problems, irrespective of their ethnic or linguistic-cultural backgrounds:

I know this from my personal experience too. Often enough I have been disadvantaged or had obstacles unnecessarily put in my way. I would like to prevent that happening again. (Yasemin, 44, Turkey, personal communication, 2021)

The woman was crying because she had no one and needed help. That touched my heart and I thought: `I was in the same situation once, I experienced the same'. I also came to Germany without knowing the language, without anything. (Oumeima, 41, Morocco, personal communication, 2021)

Meeus (2017) argues that, as a result of discrimination and marginalisation, systems of solidarity are formed to cope with everyday life among “the disadvantaged” (e.g. immigrants). He calls these systems “infrastructures of solidarity”, formed through “place-based sentiments of we-ness” (Meeus, 2017:100). This notion points to the role of place in binding people together. This place-based we-ness was also reflected in the interviews conducted in this study: “Nordstadt is like a different country. […] like a community of its own. You easily get in touch with people from so many different backgrounds” (Leyla, 25, Syria, personal communication, 2021). This is underlined by Oosterlynck et al. (2015), who describe encounters and “everyday place-based practices” (Oosterlynck et al., 2015:765) as important sources for solidarity between people in super-diverse neighbourhoods.

This leads to the assumption that the key driver of solidarity in super-diverse contexts is not common origins, norms, or values but the sense of connection brought about by collective migration histories, shared experiences of everyday life, and joint practices. This can be described as situational place-based solidarity, meaning that solidarity emerges through people who have experienced similar things living together in one place. While such solidarity does not necessarily result in the sharing of arrival-specific knowledge, it certainly promotes it.

The empirical analysis conducted in the arrival neighbourhood Dortmund–Nordstadt shows that arrival brokers, alongside more formal infrastructures, play an important role in newcomers' initial arrival process, providing them with support and sharing arrival-specific knowledge. One of their most relevant contributions is in facilitating social connections at local level.

It became clear that arrival brokers not only provide assistance in coping with everyday life or in accessing societal sectors such as employment or housing through sharing their own knowledge but also fulfil an important mediation function by helping people get in touch with others (“social bridges”) or connecting them with institutions (“social links”). The residence status of the very heterogeneous group of Nordstadt immigrants varies and thus determines their access to state support services (e.g. free language courses and so-called “integration courses” mainly target refugees). Due to their local knowledge and their many contacts, arrival brokers are able to link people to governmental support services (“linking social capital”, Woolcock, 2001), fulfilling an important function for newcomers without access to all state services or who often lack trust in government bodies or mainstream services (Quinn, 2014:67). They thus structure the often complex and not easily navigable network of formal and informal players and infrastructures. In doing so, they are able, at least partially, to fill the gaps resulting from the absence of appropriate formal support infrastructures or from access barriers (e.g. language, cultural knowledge, trust). They thus help overcome the hurdles immigrants face in accessing services.

Looking at these findings in a broader context, it becomes clear that analysing arrival processes and the role played by arrival brokers in supporting newcomers can enrich the debate on migrant integration. In most integration models (e.g. Ager and Strang, 2008), social connections play a key role. As this analysis has shown, arrival brokers fulfil an important mediation function by acting as the “connective tissue” (Ager and Strang, 2008:177) between the basic rights and opportunities associated with migrants' residence status on the one hand and their actual access to societal sectors on the other. Even if an individual's brokering practices may only be temporary, collective practices form an important permanent extension of the arrival infrastructure network, helping shape integration processes more effectively.

What many integration models do not sufficiently take into account is that resource access is context-specific (Platts-Fowler and Robinson, 2015; Phillimore, 2020) and that integration opportunities are highly dependent on local conditions (Robinson, 2010). Research on arrival processes is closely linked to the analysis of specific (arrival) spaces and the infrastructures available there (Meeus et al., 2019). This study has shown that the described processes of arrival brokering are significantly influenced by place (i.e. the arrival neighbourhood Dortmund–Nordstadt) and that this local context, with regard to arrival brokering practices, is conducive to shortening the initial arrival period of newcomers.

Robinson (2010:2461) has developed three dimensions that help illustrate how local conditions influence the opportunities for resource access: the “compositional dimension” referring to the diversity and socio-economic characteristics of the established and the newly arrived population; the “contextual dimension” referring to the available opportunity structures, such as the specific features of the neighbourhood's social and physical environment; and the “collective dimension” referring to a community's socio-cultural and historical features, such as the local social climate concerning immigration and experiences in dealing with diversity and questions of belonging.

Looking at the case of Nordstadt, it can be noted that the “compositional dimension” of this traditional arrival neighbourhood is shaped by different immigration phases over the decades. Accordingly, the neighbourhood's population is now highly diversified (e.g. in terms of ethnicity and religion, language, socio-economic situation, lifestyle, migration history, residence status, and personal resources) (Gerten et al., 2022). This contributes to a situation where many people with different characteristics live in Nordstadt and where “migrant social capital” (Wessendorf and Phillimore, 2019:124) is potentially available. Turning to the “contextual dimension”, it becomes clear that there are many social networks in Nordstadt (many of them within socio-cultural boundaries) with the potential to offer connections to newcomers. Access to these networks is provided by dense (physical) opportunity structures, such as public spaces, shops, cafés, religious spaces, and public institutions, all of which offer opportunities for interaction (Hans and Hanhörster, 2020). Turning to the “collective dimension”, a local climate of “commonplace diversity” (Wessendorf, 2014), i.e. a widely seamless coexistence, can be observed in Nordstadt due to collective migration histories and many years of experience in dealing with diversity. These collective experiences potentially contribute to people of different origins interacting and supporting each other.

Even though Nordstadt faces several challenges – the media often associate it with deprivation and crime –, the aforementioned aspects contribute to the neighbourhood providing many opportunities for supporting newcomers' arrival. The combination of the three dimensions contributes to a situational place-based solidarity between immigrants, identified in this study as the main motive for arrival brokers to support newcomers. The dimensions illustrate why arrival brokers are mainly to be found in arrival neighbourhoods and why the processes described are not to be found in this form in any other neighbourhood. It is important to note here that it is not only place that has an impact on brokering practices; conversely, arrival brokers significantly influence the different dimensions of place.

This study has highlighted the important role of established migrants as arrival brokers in super-diverse neighbourhoods. It provides empirical evidence that people with a migration background are of great relevance for the initial arrival period of newcomers, sharing their experiences and providing support. In addition, arrival brokers connect people to other individuals or institutions, thus fulfilling the important function of structuring the often-complex network of formal and informal arrival infrastructures. In doing so, they are able, at least partially, to fill the gaps resulting from the lack of appropriate formal support infrastructures or from barriers to access, thus permanently complementing the network of arrival infrastructures. As became clear, place is of particular relevance for the described processes of arrival brokering, as the social, historical, and environmental context of the traditional arrival neighbourhood is conducive to the emergence of place-based solidarity, identified in this study as the main motive for arrival brokers' practices. However, it is not only place that influences brokers' actions but also vice versa. It has been shown that the arrival infrastructure perspective for analysing migrants' brokering practices helps us understand the transformative power of migrants themselves in making, shaping, and maintaining arrival support structures (Kreichauf et al., 2020; Wajsberg and Schapendonk, 2021; Biehl, 2022).

What can be derived from these findings for policy planning? The important role of arrival brokers and the urgent need for informal support are an indication of a significant lack of appropriate formal support structures. Although there are many formal services focused on supporting arrival and integration, the findings of both this case study and those of other traditional arrival neighbourhoods suggest that capacities are either insufficient or not used sufficiently (e.g. due to language barriers or because they are not visible or sufficiently known). This gap is partly filled by arrival brokers on an ad hoc basis. However, the particular role informally played by migrants in the context of arrival is not yet sufficiently recognised and strategically considered. There are many non-governmental players making use of the arrival-specific knowledge of arrival brokers by employing them as advisors, albeit often under precarious working conditions. The great potential and the important role played by arrival brokers need thus to be better recognised by the state. For example, government players could use the resources of arrival brokers by formally integrating their skills and knowledge into their activities and services, e.g. to improve communication with newcomers.

While there is an increasing body of literature looking at both formal and informal arrival infrastructures and their relevance for migrant arrival, little is known about how formal and informal structures can be interlinked more efficiently in order to shape arrival processes more effectively. When looking at informal structures, it should also be recognised that arrival brokering practices are not always altruistic and often take advantage of people's needs. The role of these exploitative informal structures in the arrival infrastructures network also needs further investigation. Last but not least, further research is needed on how newcomers living in newly emerging arrival neighbourhoods in urban peripheries where a distinct formal and informal arrival infrastructure network has not (yet) developed can gain access to arrival-specific resources and manage their arrival processes.

The qualitative interview data contain highly sensitive information and are not publicly accessible. Please contact the author regarding any questions you might have.

The author has declared that there are no competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

I would like to thank the interviewees for sharing their perspectives with me. I also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable and helpful comments and suggestions.

This paper was edited by Hanna Hilbrandt and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Ager, A. and Strang, A.: Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework, J. Refug. Stud., 21, 166–191, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fen016, 2008.

Bakewell, O., Haas, H. de, and Kubal, A.: Migration Systems, Pioneer Migrants, and the Role of Agency, Journal of Critical Realism, 11, 413–437, https://doi.org/10.1558/jcr.v11i4.413, 2012.

Bauder, H. and Juffs, L.: “Solidarity” in the migration and refugee literature: analysis of a concept, J. Ethn. Migr. Stud., 46, 46–65, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1627862, 2020.

Bell, K.: Solidarity: https://sociologydictionary.org/solidarity/ (last access: 5 January 2023), 2014.

Biehl, K. S.: Spectrums of in/formality and il/legality: Negotiating business and migration-related statuses in arrival spaces, Migration Studies, 10, 112–129, https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnac005, 2022.

Bloch, A. and McKay, S.: Employment, Social Networks and Undocumented Migrants: The Employer Perspective, Sociology, 49, 38–55, https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038514532039, 2015.

Blommaert, J.: Infrastructures of superdiversity: Conviviality and language in an Antwerp neighbourhood, Eur. J. Cult. Stud., 17, 431–451, https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549413510421, 2014.

Boost, D. and Oosterlynck, S.: “Soft” Urban Arrival Infrastructures in the Periphery of Metropolitan Areas: The Role of Social Networks for Sub-Saharan Newcomers in Aalst, Belgium, in: Arrival Infrastructures, edited by: Meeus, B., Arnaut, K., and van Heur, B., Springer International Publishing, 153–177, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91167-0_7, 2019.

Burt, R. S.: Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition, Harvard University Press, ISBN 067484372X, 1992.

Bynner, C.: Intergroup relations in a super-diverse neighbourhood: The dynamics of population composition, context and community, Urban Stud., 56, 335–351, https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017740287, 2019.

Bynner, C., McBride, M., and Weakley, S.: The COVID-19 pandemic: the essential role of the voluntary sector in emergency response and resilience planning, Voluntary sector review, 167–175, https://doi.org/10.1332/204080521X16220328777643, 2021.

City of Dortmund: Jahresbericht Bevölkerung: https://www.dortmund.de/media/p/statistik/pdf_statistik/veroeffentlichungen/jahresberichte/bevoelkerung_1/213_-_Jahresberich_2019_Dortmunder_Bevoelkerung.pdf (last access: 5 January 2023), 2019a.

City of Dortmund: Statistikatlas Dortmunder Stadtteile: https://www.dortmund.de/media/p/statistik/pdf_statistik/veroeffentlichungen/statistikatlas/215_-_Statistikatlas_-_2019.pdf (last access: 5 January 2023), 2019b.

Dekker, R. and Engbersen, G.: How social media transform migrant networks and facilitate migration, Global Networks, 14, 401–418, https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12040, 2014.

Gerten, C., Hanhörster, H., Hans, N., and Liebig, S.: How to identify and typify arrival spaces in European cities – A methodological approach, Popul. Space Place, 29, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2604, 2022.

Glaser, B. and Strauss, A.: The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research, Sociology Press, ISBN 0202300285, 1967.

Guadagno, L.: Migrants and the COVID-19 pandemic: An initial analysis, Migration research series, no. 60, International Organization for Migration, ISBN 978-92-9068-833-4, 2020.

Hall, S., King, J., and Finlay, R.: Migrant infrastructure: Transaction economies in Birmingham and Leicester, UK, Urban Stud., 54, 1311–1327, https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098016634586, 2017.

Hanhörster, H. and Wessendorf, S.: The Role of Arrival Areas for Migrant Integration and Resource Access, Urban Planning, 5, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v5i3.2891, 2020.

Hans, N. and Hanhörster, H.: Accessing Resources in Arrival Neighbourhoods: How Foci-Aided Encounters Offer Resources to Newcomers, Urban Planning, 5, 78–88, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v5i3.2977, 2020.

Kohlbacher, J.: Frustrating Beginnings: How Social Ties Compensate Housing Integration Barriers for Afghan Refugees in Vienna, Urban Planning, 5, 127–137, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v5i3.2872, 2020.

Kreichauf, R., Rosenberger, O., and Strobel, P.: The Transformative Power of Urban Arrival Infrastructures: Berlin's Refugio and Dong Xuan Center, Urban Planning, 5, 44–54, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v5i3.2897, 2020.

Kurtenbach, S. and Rosenberger, K.: Nachbarschaft in diversitätsgeprägten Stadtteilen. Handlungsbezüge für die kommunale Integrationspolitik: https://www.hb.fh-muenster.de/opus4/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/13263/file/KurtenbachRosenberger2021NEU.pdf (last access: 5 January 2023), 2021.

Lindquist, J.: Of figures and types: brokering knowledge and migration in Indonesia and beyond, J. Roy. Anthropol. Inst., 21, 162–177, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.12172, 2015.

Lindquist, J., Xiang, B., and Yeoh, B. S.: Opening the Black Box of Migration: Brokers, the Organization of Transnational Mobility and the Changing Political Economy in Asia, Pac. Aff., 85, 7–19, https://doi.org/10.5509/20128517, 2012.

Meeus, B.: Challenging the figure of “migrant entrepreneur”: Place-based solidarities in the Romanian arrival infrastructure in Brussels, in: Place, diversity and solidarity, edited by: Oosterlynck, S., Loopmans, M., and Schuermans, N., Routledge, 91–108, ISBN 9780367218904, 2017.

Meeus, B., van Heur, B., and Arnaut, K.: Migration and the Infrastructural Politics of Urban Arrival, in: Arrival Infrastructures, edited by: Meeus, B., Arnaut, K., and van Heur, B., Springer International Publishing, 1–32, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91167-0_1, 2019.

Meeus, B., Beeckmans, L., van Heur, B., and Arnaut, K.: Broadening the Urban Planning Repertoire with an “Arrival Infrastructures” Perspective, Urban Planning, 5, 11–22, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v5i3.3116, 2020.

Oduntan, O. and Ruthven, I.: People and places: Bridging the information gaps in refugee integration, J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Tech., 72, 83–96, https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24366, 2021.

Oosterlynck, S., Loopmans, M., and Schuermans, N. (Eds.): Place, diversity and solidarity, Routledge, ISBN 9780367218904, 2017.

Oosterlynck, S., Loopmans, M., Schuermans, N., Vandenabeele, J., and Zemni, S.: Putting flesh to the bone: Looking for solidarity in diversity, here and now, Ethnic Racial Stud., 39, 764–782, https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2015.1080380, 2015.

Phillimore, J.: Delivering maternity services in an era of superdiversity: the challenges of novelty and newness, Ethnic Racial Stud., 38, 568–582, https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2015.980288, 2015.

Phillimore, J.: Refugee-integration-opportunity structures: Shifting the focus from refugees to context, J. Refug. Stud., 45, 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feaa012, 2020.

Phillimore, J., Humphris, R., and Khan, K.: Reciprocity for new migrant integration: Resource conservation, investment and exchange, J. Ethn. Migr. Stud., 44, 215–232, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1341709, 2018.

Platts-Fowler, D. and Robinson, D.: A Place for Integration: Refugee Experiences in Two English Cities, Population, Space and Place, 21, 476–491, https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1928, 2015.

Plickert, G., Côté, R. R., and Wellman, B.: It's not who you know, it's how you know them: Who exchanges what with whom?, Soc. Networks, 29, 405–429, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2007.01.007, 2007.

Putnam, R. D.: E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty-first Century – The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture, Scand. Polit. Stud., 30, 137–174, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2007.00176.x, 2007.

Quinn, N.: Participatory action research with asylum seekers and refugees experiencing stigma and discrimination: the experience from Scotland, Disability and Society, 29, 58–70, https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2013.769863, 2014.

Rebhun, U.: Immigrant Integration and COVID-19, Border Crossing, 11, 17–23, https://doi.org/10.33182/bc.v11i1.1291, 2021.

Robinson, D.: The Neighbourhood Effects of New Immigration, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 42, 2451–2466, https://doi.org/10.1068/a4364, 2010.

Saltiel, R.: Urban Arrival Infrastructures between Political and Humanitarian Support: The “Refugee Welcome” Mo(ve)ment Revisited, Urban Planning, 5, 67–77, https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v5i3.2918, 2020.

Saunders, D.: Arrival City: How the Largest Migration in History is Reshaping Our World, Windmill Books, ISBN: 9780307388568, 2011.

Schillebeeckx, E., Oosterlynck, S., and de Decker, P.: Migration and the Resourceful Neighborhood: Exploring Localized Resources in Urban Zones of Transition, in: Arrival Infrastructures, edited by: Meeus, B., Arnaut, K., and van Heur, B., Springer International Publishing, 131–152, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91167-0_6, 2019.

Schrooten, M.: Moving ethnography online: researching Brazilian migrants' online togetherness, Ethnic Racial Stud., 35, 1794–1809, https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2012.659271, 2012.

Schrooten, M. and Meeus, B.: The possible role and position of social work as part of the arrival infrastructure, Eur. J. Soc. Work, 23, 414–424, https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2019.1688257, 2020.

Simone, A.: People as Infrastructure: Intersecting Fragments in Johannesburg, Public Culture, 16, 407–429, https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-16-3-407, 2004.

Small, M. L.: Someone To Talk To, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780190661427, 2017.

Spencer, S. and Charsley, K.: Reframing “integration”: acknowledging and addressing five core critiques, Comparative Migration Studies, 9, 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-021-00226-4, 2021.

Steigemann, A.: The Places Where Community Is Practiced, Springer Fachmedien, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-25393-6, 2019.

Thiery, H., Cook, J., Burchell, J., Ballantyne, E., Walkley, F., and McNeill, J.: “Never more needed” yet never more stretched: reflections on the role of the voluntary sector during the COVID-19 pandemic, Voluntary sector review, 12, 459–465, https://doi.org/10.1332/204080521X16131303365691, 2021.

Tuckett, A.: Britishness Outsourced: State Conduits, Brokers and the British Citizenship Test, Ethnos, 7, 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2019.1687543, 2020.

Udwan, G., Leurs, K., and Alencar, A.: Digital Resilience Tactics of Syrian Refugees in the Netherlands: Social Media for Social Support, Health, and Identity, Social Media + Society, 6, 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120915587, 2020.

Valentine, G.: Living with difference: reflections on geographies of encounter, Prog. Hum. Geog., 32, 323–337, https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133308089372, 2008.

Vertovec, S.: Diversities old and new: Migration and socio-spatial patterns in New York, Singapore and Johannesburg, Global diversities, Palgrave Macmillan, https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137495488, 2015.

Wajsberg, M. and Schapendonk, J.: Resonance beyond regimes: Migrant's alternative infrastructuring practices in Athens, Urban Stud., 59, 2352–2368, https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980211044312, 2021.

Wessendorf, S.: Commonplace diversity. Social relations in a super-diverse context, Palgrave Macmillan, https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137033314, 2014.

Wessendorf, S.: Pathways of settlement among pioneer migrants in super-diverse London, J. Ethn. Migr. Stud., 44, 270–286, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1341719, 2018.

Wessendorf, S.: “The library is like a mother”: Arrival infrastructures and migrant newcomers in East London, Migration Studies, 10, 172–189, https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnab051, 2022.

Wessendorf, S. and Phillimore, J.: New Migrants' Social Integration, Embedding and Emplacement in Superdiverse Contexts, Sociology, 53, 123–138, https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038518771843, 2019.

Wilson, H. F.: Arrival cities and the mobility of concepts, Urban Stud., 59, 3459–3468, https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980221135820, 2022.

Woolcock, M.: The Place of Social Capital in Understanding Social and Economic Outcome, Canadian Journal of Policy Research, 2, 65–88, 2001.

The literature indicates that there are also a lot of volunteers without a migration background who help newcomers with their language skills or with relevant settlement information (Kohlbacher, 2020; Saltiel, 2020). However, the focus of this study is on immigrants themselves, analysing their specific role in shaping arrivals.

Reflections on geographies of encounter are widely and often normatively discussed both in urban geographic research and in planning practice. In the scientific discussions, the value of everyday encounters for reducing prejudices and building up social capital is emphasised (for an overview, see Hans and Hanhörster, 2020).

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Accessing arrival-specific resources in super-diverse neighbourhoods

- Research area and methodology

- Empirical findings: how and why do arrival brokers support newcomers?

- Discussion: arrival brokers' relevance for newcomers' resource access

- Conclusions

- Data availability

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Accessing arrival-specific resources in super-diverse neighbourhoods

- Research area and methodology

- Empirical findings: how and why do arrival brokers support newcomers?

- Discussion: arrival brokers' relevance for newcomers' resource access

- Conclusions

- Data availability

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References