the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Designing landscapes of affordances for ageing in place

Tania Zittoun

Fabienne Gfeller

Aurora Ruggeri

Isabelle Kloepper

This paper aims to contribute theoretically, methodologically, and empirically to research and interventions regarding ageing in place. Theoretically, the paper contributes by drawing on the literature on landscapes of care and landscapes of affordances to suggest a multiscalar and more-than-human approach to ageing in place. Methodologically, we argue that studying ageing in place requires a participatory and translational methodology. Participatory methods are, on one hand, a prerequisite for an understanding of how older adults live their daily lives and particularly use a “landscape of affordances” in their social and material environment. A translational process, on the other hand, is necessary to elaborate research results incrementally across the different stages that lead to interventions on the ground. Finally, empirically, we draw on results of a study based on go-along interviews, photographic observations, and biographic interviews. In its empirical part, our paper describes the difficulties and gains of the different aspects of this participatory and translational process. In summary, the paper both develops the conceptual underpinnings of “ageing in place” and informs the methodologies of applied research in this domain.

- Article

(2257 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Ms Dujardin lives on an old farm, which she shares with her daughter's family with whom she is on bad terms. The house is located at the top of a village on a slope of the mountain overlooking the lake. Every day, she goes for a walk in the field and rests on a bench at the fringe of the forest; this is also the only flat pathway, parallel to the slope, on which she can walk. She likes the place where she lives, yet in the village, the post office and the school are long closed. As she has no driving license anymore and the bus that connects the village to the rest of the canton circulates only occasionally, it is difficult for her to meet her last living friends or to go to shops and cafés, unless someone drives her. However, to provide new opportunities for social interaction for inhabitants like Ms Dujardin, the commune recently decided to refurbish the old school, changing it into a meeting locale.

This transformation of an abandoned school in a Swiss commune derives from participatory action research in the Swiss canton of Neuchâtel, entitled “ReliÂge”, in which the authors of this paper have been involved. It is the result of a process during which participants – older persons, care workers, state officials, civil society organisations, geographers, and psychologists – mapped resources for and obstacles to older people's everyday activities in order to design communal action plans for older people. Drawing on this collective experience, the aim of this paper is to contribute to studies on ageing in place (Bigonnesse and Chaudhury, 2022; Forsyth and Molinsky, 2020) and landscapes of care (Milligan and Wiles, 2010) at both a theoretical and a methodological level.

Our research was part of a national programme in Switzerland aiming to prevent the social isolation of old people. Social isolation and loneliness, its subjective counterpart, are today widely considered major societal problems and have come to constitute a crucial framing for the definition of public policies concerning ageing. Responding to this “declared loneliness epidemic” and to estimates of its public health costs, a market of solutions has flourished, including, in particular, the development of specifically designed companion robots (Pratt et al., 2023:2063). The loneliness framing and its technological corollaries define the “ageing problem” as being primarily individual rather than related to the roll-back of care services by the state (Power and Hall, 2018). It takes as a given that social isolation and the experience of loneliness are the main issues and practical problems that old people face in their daily lives. However, empirical studies tend to question this approach. Drawing on fieldwork in Canada, Couturier and Audy (2016) argue, for instance, that there is an “over-problematisation” of social isolation and loneliness. In this context, more concrete issues and the fact that isolation can be chosen and not experienced as loneliness tend to be disregarded. The focus on loneliness also corresponds to a “deficit model” (where old people and persons living with a disability or a mental health diagnosis “lack something or someone”), criticised in disability studies for depoliticising health and care issues and downplaying the agency and resources of concerned social groups (Butler and Parr, 1999). For these reasons, we distance ourselves in this paper from such framing and instead ask the following questions: what are the resources (persons, objects, experiences, knowledge, technological devices, cultural artefacts) old persons mobilise to support activities that are meaningful for them in their daily lives? What are the obstacles (elements or events) hindering (totally or partially) the accomplishment of these activities? How can the analysis of these practices advance the conceptualisation of ageing in place and inform public policies?

To respond to these questions, the paper is divided into three parts. In the first, theoretical part, we position our paper in the interdisciplinary literature on ageing. We develop an original framework combining three complementary approaches: studies on landscapes of care in human geography (Milligan and Wiles, 2010), new directions in the sociocultural psychology of development (Grossen et al., 2022; Zittoun and Baucal, 2021), and recent advances in affordance theory (Chemero, 2003; Ramstead et al., 2016). We propose a multiscalar approach to ageing in place, articulating landscapes of care and landscapes of affordances. In the second part, we present the context in which our project took place and our participatory and translational methodology. We argue first that participatory methods are a prerequisite for an understanding of how older adults live their daily lives and particularly how they use a “landscape of affordances” (Ramstead et al., 2016) in their social and material environment. Second, we argue in favour of a translational process (Drolet and Lorenzi, 2011; Parnell and Pieterse, 2016) allowing for site-specific applications of the research's results. In the third part of the paper, we highlight the expected and less expected contributions of this project: how it allowed the design of targeted interventions and how the process itself produced new resources for ageing in place.

“Ageing in place” has become a paradigm in public policies regarding older persons. Ageing in place refers to the possibilities for older adults to live in their community rather than in nursing homes. Many countries in the global north, Switzerland among them, have been developing such policies since the 2000s. During the same time span, ageing in place has also become an expanding interdisciplinary research domain (Rogers et al., 2020). Studies of ageing in that field show that ageing in place corresponds to the aspirations of most older persons but that it took time to consider the phenomenon from their perspective (Wiles et al., 2012; Wiles and Andrews, 2020). Older people describe what matters in places as extending widely beyond their own homes (Wiles et al., 2012). Work by geographers but also in other disciplines related to environmental gerontology has thus contributed to consider place “in a much more `geographically elastic' way, which incorporates dwelling, neighbourhood, community, region, and nation” (Andrews et al., 2007:158). Studies of ageing in place also converge on the fact that the aspects that are important for people ageing in place extend far beyond the functional characteristics of place and space, such as services and infrastructures, to encompass a wide range of material, social, and affective phenomena (Bigonnesse et al., 2014; Bigonnesse and Chaudhury, 2022).

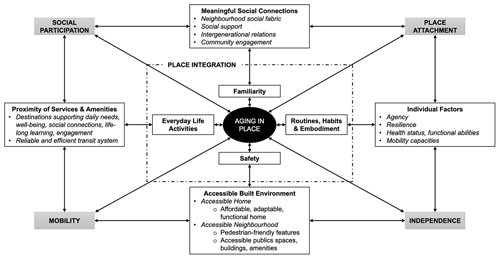

The production of scholarship in this domain has expanded at the same pace as this increasing breadth of themes and questions. A 2020 scoping review analysed over 3600 publications related to ageing in place and found that they dealt with five key themes: place, social networks, support, technology, and personal characteristics (Pani-Harreman et al., 2020). Considering this breadth of scholarship, it is important to develop a model or analytical framework to better conceptualise ageing in place and logically articulate its constitutive dimensions. Such an effort has been made recently by Bigonnesse and Chaudhury (2022) on the basis of capability theory (Fig. 1). In their framework, ageing in place is “influenced by five central components: (1) place integration, (2) place attachment, (3) independence, (4) mobility, and (5) social participation. These five components are, in turn, influenced by four factors: individual characteristics, accessibility of the built environment, proximity of services and amenities, and development and maintenance of meaningful social connections” (Bigonnesse and Chaudhury, 2022:64).

Figure 1Conceptual framework of ageing in place in a neighbourhood environment from a capability approach (source – Bigonnesse and Chaudhury, 2022:64).

Central components directly influence ageing in place, while the four factors indirectly influence it. Moreover, these factors and components such as mobility and independence are mutually constituted. Having the capacity to drive a car or take public transport are factors influencing independence. As a consequence, Bigonnesse and Chaudhury (2022:65) define ageing in place “as an ongoing dynamic process of balance enabling an individual to develop and maintain place integration, place attachment, independence, mobility, and social participation”.

We share many principles of this broad and carefully designed framework, among which are the focus on agency, an ecological perspective, and multiple geographic scales. We also see some limitations in the capability-based approach that foregrounds the individual but does not give much weight to structuring factors related to the political economy of ageing. In this respect, it is important to observe that the de-institutionalisation of elder care in Switzerland is embedded in neoliberal austerity politics favouring private and commercial solutions (Schwiter et al., 2018). However, local and regional policies also significantly shape access to housing and mobility and the provision of an ageing-supporting environment. In our case, efforts in the canton of Neuchâtel in recent years to develop varied housing solutions and communal action plans are testimonies to state action that cannot be reduced to the sole engineering of neoliberalisation (Gfeller et al., 2022). Moreover, Bigonnesse and Chaudhury's framework tends to uncritically adopt an individualistic definition of independence as “the ability to function unaided” (Schwanen et al., 2012:1314). Although the question of independence is not central to our research, our empirical results below show that ageing in place is, from the viewpoint of our participants, not related to independence as self-reliance but rather to capacities of self-determination relying also on various other aspects both human, such as a shop owner, and nonhuman, such as a bench in a park.

To further develop a conceptual framework and toolbox for studying ageing in place, we suggest a stronger scalar articulation. More specifically, we suggest articulating the structural dimensions of a landscape of care with a vocabulary allowing the analysis of older people's everyday social and material environment through the concept of a landscape of affordances.

In what follows, we explain why thinking in terms of landscapes of care and affordances is helpful for studying ageing in place.

2.1 Landscapes of care

Work on the concept of the landscape of care was not initiated in the specific field of ageing studies, although the authors of the seminal text in this domain (Milligan and Wiles, 2010) have worked on ageing. It was rather thought of more broadly as a “framework for unpacking the complex relationships between people, places, and care” (Milligan and Wiles, 2010:736). This framework has three main characteristics. First, the landscape metaphor indicates a perspective on care that goes beyond the traditional dyad of care-giver/care-receiver to envisage care as enacted within a network. Second, it emphasises that care is shaped by a multiplicity of places (institutions, homes, neighbourhoods) at different scales (from the international to the embodied and interpersonal).1 Third, landscapes of care are infused with power-laden relations characterised by economic and notably gender-based inequalities, as care work is very often accomplished by female relatives on an unpaid basis.

Considering ageing in place as a landscape of care highlights the importance of attending to the whereabouts of care and to the multiple scales involved. Ageing at home in Japan, for instance, is facilitated by migration policies allowing low-paid Filipino nurses to work on a permanent basis in the homes of old people, a rarity in a country with a long tradition of very restrictive migration policies. Thus, legal, economic, and political factors are forces that structurally shape local configurations of a landscape of care. The latter is also populated by more-than-human elements (to continue with the Japanese example): not only Filipino nurses but also robots, trees in parks, or sidewalks navigable by wheelchairs or walkers.

The diversity of entities that make ageing-supportive landscapes of care has been emphasised by the post-human turn in gerontology, consisting of a de-centring of the human in ageing studies “in favour of a broader sweep of actors and forces” (Andrews and Duff, 2019:49). Regardless of the debates about whether humanism should be replaced or complemented (Brinkmann, 2017) and the adequacy of the term “post-human” (we tend to prefer the more precise “more-than-human”), these approaches contribute, in our view, to the enrichment of an approach of ageing in place where “place” is envisaged in a broad sense, i.e. as made of affective, social, and material elements and their assemblage in a continuous process of becoming.

We find it particularly fruitful and relevant to our study to analyse how these various resources in a landscape of care can (or cannot) be supported or used. This requires, we argue, more than what a post-humanist position – which tends to be a quite general “navigational tool” (Andrews and Duff, 2019:47, quoting Rosi Braidotti) rather than an approach or a concept – can offer. We suggest that recent developments in affordance theory can provide the relational language needed for this study.

2.2 Landscapes and fields of affordances

The relations between subjects and material objects lie at the core of James Gibson's affordance theory (Gibson, 1986). Developing an ecological theory of perception, Gibson approached perception as an embodied and mobile process compared to the Cartesian tradition where the subject was primarily immobile and contemplative. Affordances are for Gibson what sit between the perceiving/acting subject and her/his material environment. Recent work in affordance theory has led Gibson's theory in directions that are interesting for the consideration of old people's everyday spaces and places that we explored in the context of our study. Chemero (2003), in particular, has developed a more relational affordance theory, “while previous (post-Gibson) attempts to set out an ontology of affordances have typically assumed that affordances are properties of the environment” (Chemero, 2003:182). Chemero argues that affordances “are relations between particular aspects of animals and particular aspects of situations” (Chemero, 2003:184). While Chemero's theory of affordances is useful for its emphasis on relations, it is restricted to physical action. More recently, Ramstead et al. (2016) have extended the conceptualisation of affordances to encompass both physical and “sociocultural forms of life”. They distinguish between “natural” and “conventional” affordances. Natural affordances are possibilities for action, “the engagement with which depends on an organism or agent exploiting or leveraging reliable correlations in its environment with its set of abilities. For instance, given a human agent's bipedal phenotype and related ability to walk, an unpaved road affords a trek” (Ramstead et al., 2016:2). Conventional affordances are possibilities for action, “the engagement with which depends on agents skilfully leveraging explicit or implicit expectations, norms, conventions, and cooperative social practices” (Ramstead et al., 2016:2). Thus, for conventional affordances, interaction with others and understanding how they think and act are crucial. This distinction invites us, when we study older people's everyday lives, to look at how their relations with their material, social, and affective environment provide them with resources for ageing in place. It also implies that these resources are often relationally produced through a combination of natural and conventional affordances. For instance, the regular terrace meetings with a drink and snacks that create social bonds at one of our study sites are resources for ageing in place consisting of both a built environment with gardens and terraces and the knowledge and know-how allowing older persons to be a part of this specific social situation.

The other useful distinction Ramstead and colleagues propose is between the landscape of affordances, which is made of “the ensemble of available affordances in an environment” and the field of affordances, which corresponds to the affordances with which an organism actually engages (Ramstead et al., 2016:4). In other words, the difference here is between a set of possibilities and those that are activated. Approaching the everyday environment or “place” of old people as a landscape of affordances means that affordances do not present themselves as discrete elements but rather “as a matrix of differentially salient affordances with their own structure or configuration” (Ramstead et al., 2016:4). The favourite bench with a view of the valley used by participants at another of our study sites represents a resource in a field of affordances because it is reachable using a walker along a pedestrian path.

Finally, “the field of affordances changes through cycles of perception and action” (Ramstead et al., 2016:5). This came out clearly in our in situ study of participants' fields of affordances: participants' narratives emphasise these changes due, for instance, to the loss of a partner or to health problems. These changes also appear when contrasting the practices and discourses of participants of various ages and conditions. A gym course in another village used to be an important resource for a participant now in her 80s when she was 10 years younger, but it is not the case any longer. Material and social environments also evolve: shops close, buildings deteriorate and new ones are built, trees grow, neighbours move, etc. This also changes the landscapes and fields of affordances. In other words, affordances are always in a state of becoming. Therefore, they should be understood and analysed through a life-course perspective (Elder and Giele, 2019; Levy et al., 2005), where the becoming of the person is understood via the material and semiotic guidance of the environment, both at the microscale and in larger sociocultural terms (Grossen et al., 2022). Thinking in such terms invites us to consider the fact that people engage in specific activities and interactions while actively making sense of them, with a history, memories, and expectations and imagination of alternatives (Zittoun, 2022). Such a developmental stance sees older persons as not only “ageing” in place but actively “growing older”, i.e. reflexively handling evolving situations based on their life experiences.

In this section, we have suggested that the conceptual vocabulary we propose – landscape of care, natural and conventional affordances, landscape and field of affordances, and experiencing and developing – is necessary, first, to embed a study of ageing in place in a larger political economy of ageing and, second, to closely study, at the other end of the spectrum, how the everyday environment of old people can provide affordances that can be used as resources for growing old in place.

In the next section, we show how such theorisation enabled us to approach an intervention aimed at avoiding the isolation of older persons in a Swiss canton.

Our research took place when the two senior authors of this article were contacted by the public health service of the canton of Neuchâtel in Switzerland to collaborate on a programme to prevent the isolation of its older population. We show here the context of this initiative, how we reframed the problem we were asked to find solutions to, and the research methodology we proposed. These elements are part of the structural conditions redefining a specific landscape of care.

In 2007, the Swiss government published a strategy regarding ageing, aiming to “increase the autonomy” of older adults, notably by creating “neighbourhoods for all ages” (Conseil Fédéral, 2007:43–44). Like many other countries at that time, Switzerland took an explicit policy turn favouring ageing in place rather than in retirement homes. This turn was motivated by a mix of humanist momentum to promote the quality of life and independence of older people and by the (quasi-ubiquitous) neoliberal doctrine of a transfer of costs and responsibilities from states to citizens. The promotion of the independence of old people is to be understood, in this context, as part and parcel of a “rescaling of responsibilities with regard to health, wellbeing, and social care from the state to the level of older people themselves and to a lesser degree their networks of relatives, friends, and others” (Schwanen et al., 2012). In a country where in most domains (except sectors such as military defence and foreign affairs) the federal state essentially provides strategies and policy frameworks, legislation and the implementation of policies are effectuated at the cantonal (i.e. regional) level. Therefore, if in recent years the general trend has been the development of a policy of “ageing in place”, the translation of this policy into institutions, laws, and action has been quite varied in Switzerland (Schwiter et al., 2018). In the region we study, this translated to a new “medico-social plan” aimed at supporting ageing in place by strongly encouraging the construction of new intermediary housing in each neighbourhood and village, by reducing the number of beds in full-time nursing homes, and by developing a coordination and counselling network, “centralising all information about care and support for older people and their relatives” (Conseil d'Etat, 2012, 2015; Gfeller et al., 2022). This project has been in development since 2012.

This project began in 2006, caused important legal changes in the cantonal law in 2012 and 2021 (Conseil d'Etat, 2021), and is still developing.

In parallel, the coordination of communal action plans for the promotion of older people's health is one of the tools used by Swiss cantons to implement the national strategy. The development of these plans is supported by a publicly and privately sponsored foundation, Promotion Santé Suisse (Swiss Health Promotion), through nationwide calls for projects. In 2019, Promotion Santé Suisse launched a call for projects aiming to prevent the social isolation of older people. The research on which this article is based was conducted in this context and was led by a consortium including cantonal authorities, an inter-communal association involved in territorial development, and academics2. It was effectuated between 2020 and 2022 in collaboration with older persons, representatives of communes, and civil society organisations.

Hence, both the regional development of a new medico-social plan with important legal measures to support ageing in place and the local implementation of measures to prevent social isolation constitute structural conditions shaping the specific landscape of care.

Our project approached the question of social isolation while maintaining distance from the “deficit model” in ageing and disability studies (Butler and Parr, 1999). Rather than focusing on isolation per se, and guided by our theoretical framework, we focused on participants' fields of affordances by analysing the resources they used to accomplish activities meaningful to them – mostly involving or allowing social interactions (from gardening to shopping and seeing friends and family) – and focused on obstacles that hinder or complicate the accomplishment of these activities. To define appropriate interventions from older people's perspectives, we engaged in participatory action research. In the section below, we describe our methodology in detail, as it allows us to show how the concepts we propose can inform research and action on ageing in place.

The study design

In our introduction, we explained why we chose not to focus on social isolation per se but rather on how old people manage to maintain meaningful activities in their daily lives. We translated a political goal, itself translating a societal model of ageing where old people are ideally independent yet socially connected, which was put in place through top-down logic where the health office takes preventive measures through new housing models, into a bottom-up study design focusing on old persons' agency and resources and how they can be reinforced. This redefinition of the objective of the study compared to the mandate given by the funder was made explicitly and with the support of the steering committee of our project, which included representatives of the health office of the canton, members of an inter-communal association involved in territorial development, representatives of a foundation supporting older people in Switzerland, presidents of communes, and researchers (the authors of this paper). As a consequence, our research documented the diversity of modes of lives of older persons, their daily activities, and the variety of landscapes of affordance, both natural and conventional, that people encounter in the region. Three communes, a rural commune, a small peripheral industrial town, and a suburban neighbourhood of the canton's main city, were chosen as study sites. Sites were chosen to maximise variability across cases in terms of location (suburban vs. countryside), topography (flat vs. slope, near a forest vs. to the lake), size (isolated houses around small villages, large village, dense suburban area), the presence of services (shops, cafés, and post offices or none) and transport (two locations are connected by multiple public transport links and one just by three buses per day), and the history of previous interventions (the suburban location had been the target of earlier urban intervention measures – i.e. benches added on a slope). Such variability was used to envisage a diversity of situations and thus interventions apt to address this diversity rather than one-size-fits-all solutions. This choice was functional for the objective of the research: developing a toolbox for the design of locally relevant action plans for older persons at commune level that could be proposed to all communes in the canton.

Data collection consisted of three main steps distributed over a year: exploratory observation in the three communes, inaugural workshops, and go-along interviews followed by interviews combining biographical questions and problem-centred questions.

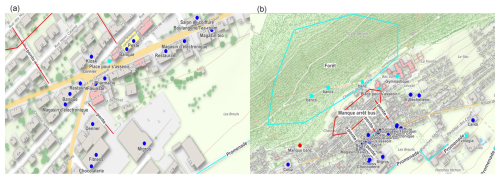

The aim of exploratory observation was to get a sense of the places and landscape of affordances: observing elements (or the absence thereof) such as sidewalks, parks, viewpoints, shops, post offices, garbage collectors, and cafés (Fig. 2).

Figure 2Photographs taken during the preliminary mapping of landscapes of affordances at the study sites.

Three inaugural workshops, one in each commune, were organised to complement this preliminary mapping and to start moving from landscapes to fields of affordances. Participants (20 per site on average) were contacted through the formal and informal networks of the various teams participating in the project. The aim of the workshops was also to launch the study as a public event in order to create interest and participation in the process. Participants were asked to describe their activities, the obstacles they met when conducting them, and resources that they could use to achieve them and to mark them using three colours on the maps (Fig. 3). This step enabled us to get a first collective description of people's fields of affordances and once these were synthesised, a first map of fields of affordances in each commune.

The third step of the research aimed to map fields of affordances more precisely on the basis of data collection of participants' activities. This phase constituted the core of the data collection. Drawing on previous work by one of the team members on mental health (Söderström, 2019), it involved go-along interviews.

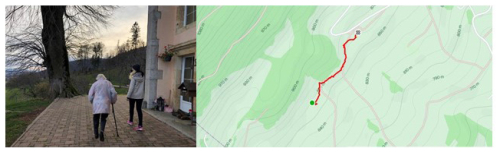

Participants of the go-alongs were identified at the first workshop as being willing to participate further in the project. Further participants were identified by snowballing. Each participant (10 per site) was accompanied by two members of the research team for a walk corresponding to their daily (or at least regular) activities or tour (Fig. 4). The average age of go-along interviewees was 75. The youngest participant was 68 years old and the oldest 93. For each site, we created a group of 10 participants with a balance in terms of age, gender, and socio-economic background. The relatively small sample is due to the fact that go-along interviews with older persons are very time-intensive.

Figure 4A go-along interview with Anna (86) and the map of her habitual daily walk. The base layer comes from the Système d'information du territoire neuchâtelois: https://sitn.ne.ch (last access: 10 March 2025).

Pictures (300 in total) were taken of significant places, obstacles, or natural/conventional affordances, and the conversations were recorded.

After the go-along, semi-structured interviews were carried out at participants' places. This was a means to include their homes in their fields of affordances: significant objects, the organisation of domestic space, obstacles such as stairs or a badly placed oven, or resources such as a ramp. We collected 30 (10 per site) go-along interviews with older persons, each followed by a semi-structured interview that lasted between 105 and 230 min, during which pictures were taken. To complement data collection, we interviewed 35 persons regularly in contact with older people – café owners, social workers, priests, and nurses – and made observations at the study sites during the 3 months of fieldwork. The empirical material (900 pages of transcripts and 300 photographs) was stored and then analysed using Atlas.ti.

As the aim of the paper is primarily conceptual and methodological, we focus here on the synthetic results of the study and do not detail differences between the three study sites. In the first part of this section, we discuss the landscapes and fields of affordances we identified and link them, in the second part, to a broader landscape of care.

To identify fields of affordances, we assessed the relative importance of activities, resources and obstacles for participants based on two indicators: (i) the frequency with which they are mentioned and (ii) the way they talk about them (e.g. with passion or joy).

4.1 Activities, obstacles, and resources

For participants, the most significant daily life activities in their communes were those centred on collective exchange (such as sharing meals or coffee), which could take place at people's places of residence, at local cafés, or in public spaces. One of the participants, Geneviève3, summarises a recurring argument about the importance of collective exchanges in this way:

So, it's easy for me to exchange ideas or help someone else … I don't care whether it's me or someone else who's doing it, as long as there's a movement, a dynamic, and a reflection. But where there's a simple exchange, which can help the community move forward, that's really where … I find my reason for living.

The three other meaningful activities were related to the home (cooking, cleaning, shopping, gardening, decorating), to activities that stimulate the mind (such as classes and discussions, games, painting, music, travels), and to activities focused on the body and physical health (medical care, sport).

Participants mobilised a variety of resources to carry out these activities: social resources including relationships with family and friends or commitments to associations. These social resources are seen as central to forms of social recognition. As André put it laughing:

To have attention, to be worthy of attention, and to have a special moment is always to remain someone among others. That's my slogan.

Symbolic and cognitive resources, including courses and workshops but also spirituality and the use of and access to information and communication technologies, were also seen as important for living a meaningful life. This, for instance, is how Hugo describes his daily routine:

I get up in the morning to do tai chi, I start doing exercises, kung fu, I look at a lot of masters' programmes on the internet, and I start photocopying the movements, that's it, then I listen to music and then I do my walk.

Material resources (a garden, a bench, shops, means of transport) were mentioned as the fourth crucial type of resource.

Participants also faced obstacles of various sorts when carrying out these activities: the progressive loss of social ties following the death of friends or moves by members of their family, the closure of small stores offering opportunities for social interactions (usually because of structural conditions – the retirement of a café owner or closure of a post office for economic reasons), slopes (that are steep in the region), insufficient public transport (often reduced because the population is ageing), unappreciated changes in the landscape, the absence of educational or cultural offerings, and the loss of physical capacities. Commenting on the latter, Gaëtan told us:

I would have liked to do kite-surfing. I did the beginnings of windsurfing … Ah I'm sorry, that would have really pleased me. But now I don't have the strength. I didn't believe in it, but even to open the bottle sometimes I have trouble. We decline.

These results are resonant with the five dimensions of ageing in place identified by Bigonnesse and Chaudhury's (2022) capability approach: place integration, place attachment, independence, mobility, and social participation. Central to our action research was the next step in our analysis, which allowed us to spatialise these elements. Based on the go-alongs, the photographs, and the interviews but also on the two workshops at each site, we mapped the activities for each commune in order to understand concretely how they take place. These maps represent, we argue, fields of affordances: a relational view of how old people practice their daily environment in its different dimensions (social, material, affective). They were produced using the Geographic Information System of the Neuchâtel canton, allowing zoom in and zoom out functionalities and thus a multiscalar vision of these elements (see Fig. 5).

Thus, the fields of affordances in Cernier (Fig. 5 below), one of our three sites, highlight the role of clustered shops in the centre (that tend to decrease and scatter), favourite walks and the forest, and benches but also the problems related to slopes without handrails and the absence of benches, buses, or bus stops.

Figure 5The main features of participants' fields of affordances in the centre of Cernier (a) and a broader view of the same commune (b). Cultural and leisure resources are in light blue, commercial resources and services in dark blue, and obstacles in red. The base layer comes from the Système d'information du territoire neuchâtelois: https://sitn.ne.ch (last access: 10 March 2025).

These maps of fields of affordances were instrumental in the next step in our project: the translation of research results into action plans. This phase involved other actors in the landscape of care: the canton, the communes, and crucially a partner coordinating the various scales of the state.

4.2 Translating research results into interventions

The translational process included a research report for the communes (Gfeller et al., 2022) and a repertoire of possible actions at each site. Our recommendations identified features of the landscape of affordances that, on the one hand, should be preserved, valorised, or reinforced – e.g. natural affordances such as benches and handrails on slopes – and, on the other hand, should be created, so as to reinforce older people's fields of affordances. Some of these features were common to the three communes: a need for better possibilities of mobility and access to shops, doctors, or recycling centres. There was also a common need for indoor places to meet that could accommodate different activities (cafés or an open locale). The flexibility (through possible rearrangement of furniture) and self-management of these places by old people would enhance their appropriation and strengthen these affordances. Other features were more specific to a commune: in the rural commune, collective transport is needed to go shopping, while specific routes need new public lighting in the suburban commune, etc. Thus, the research report created links between personal practices and the communal scale of the landscape of care defined by a list of possible interventions.

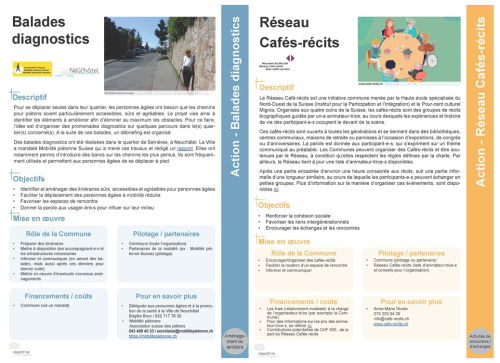

The translational process was taken further by the inter-communal association, which was part of the action research consortium and thus of the structural conditions of the translation. The organisation is a regular interlocutor with the local state (at both the cantonal and communal level) in different public policies. It assisted with the development of the research with the communes and followed the study participants from the start. Therefore, it was, on the one hand, in a good position to translate research results into a language and tools easily manageable by institutional actors. On the other hand, it was able to connect our locally grounded research with other scales and actors in the landscape of care, such as the coordination of communal public health officials. Drawing on this experience, this partner organisation designed interventions that drew on research results responding to identified needs and also on measures developed in other Swiss cantons. This resulted in a catalogue of 67 measures (https://objectif-ne.ch/?projets=reliages-prevenir-lisolement-des-65, last access: 7 March 2025), each of which is described by a technical data sheet with examples, guidelines, pictures, and references. These measures correspond to extensions of various dimensions of the landscapes of affordances in the communes. In the register of natural affordances (Ramstead et al., 2016), diagnostic walks (see Fig. 6, left panel) are, for instance, a procedure that allows us to identify uneasy pedestrian pathways and to design improvements such as street furniture to create a break in a steep slope. In the register of conventional affordances (Ramstead et al., 2016), story cafés, for instance, are meetings in public spaces where life stories are shared to develop intergenerational exchanges and interactions (Fig. 6, right panel). In both cases, these are site-relevant interventions, as our study shows, but were first developed elsewhere in Switzerland. Thereby, the process allowed a mobility of interventions across places and choices based on the specificity of contexts. It articulated local fields of affordances with solutions, developed by public services, associations, or foundations like Pro Senectute, constituting a landscape of care for old people, which is quite varied across cantons in a federal country like Switzerland.

Figure 6Left panel – the data sheet for the diagnostic walks; right panel – the sheet for the story cafés (© objectif.n.).

This translational process was also participatory: a workshop was organised in each commune to present research results and possible site-specific interventions. Participants were invited to react or state non-identified needs. Workshops also worked as spaces where participants could directly address their local representatives, often informing them about features of their daily lives that these representatives ignored. For instance, in one commune, participants informed the president of their commune, to his surprise, that they had to pay full price for public transport (often representing more than the price of the daily food allowance), which was the reason why they could not go shopping in the city centre. Thus, these workshops, organised like “hybrid fora” (Callon et al., 2009), functioned as not only a means to further enrich the action research but also an unusual platform of exchange between older people and local officials.

In the wake of these workshops, each commune could choose to implement one of the proposed interventions. This intervention was partly funded by the project. For instance, as alluded to in our introductory vignette, in the most isolated village of the rural commune, in which there was no public café or shop and where the post office had been closed, the commune decided to renovate the former school, located in the centre of the village, and turn it into a meeting venue for older persons.

Finally, a forum was organised where all communes of the canton were invited to encourage a scaling-up from the three pilot sites to the regional (cantonal) level.

The participatory and translational dispositive we planned and accompanied aimed to prevent the isolation of older persons in the canton of Neuchâtel. Rather than intervening at the individual level – e.g. targeting people suffering from loneliness – we considered the landscape of care at the scale of the canton. We used three contrasting study sites to map out the local landscapes of affordances enabling older persons to accomplish their daily activities and maintain a social life.

Implementation was then handed over to the communes but also to a broader network of actors involved in (and partly constituted by) the project, thanks to a complex structural scheme. Some concrete measures were quickly implemented in the target communes. In the small town, for instance, pavement was remade to make it less slippery, while handrails and sitting spots were added. The same commune opened a weekly class on the use of digital technologies. In the urban neighbourhood, a restaurant has introduced regular meetings for older people.

Action research like the one we describe in this article is always at risk of being a temporary circus: everything vanishes when the circus (and its sponsors) leave the area. Structural measures were taken to avoid this “circus effect”. First, the canton made a budget available, managed by the inter-communal association, to motivate communes in the canton (whether participating in the project or not) to implement the proposed measures. Second, the inter-communal association organised workshops and training for all the communes of the canton to provide them with a usable methodology based on each commune's landscape of affordances.

To summarise, our participatory action research had two main outcomes, a voluntary and an involuntary one. The voluntary outcome is that, thanks to the coordination of actors of the landscape of care at the cantonal level, we were able to design and implement targeted measures that reinforced and enriched the communes' landscape of affordances for old persons, thus creating better conditions for people to grow older in place. The involuntary outcome of this process is that it produced, in and of itself, a new set of conventional affordances: older persons who took part in a workshop during the Covid-19 pandemic were able to meet other persons in safe conditions; older persons came to know each other and know about activities in their regions; and commune leaders had, sometimes for the first time, a dialogue with their older citizens. In other words, all participants came to expand their fields of affordances during the action research process.

This article is our effort to understand the lessons we learned at a conceptual and methodological level from participatory action research. First, we see our project as an attempt to bridge two aspects insufficiently present in recent conceptualisations of ageing in place: the wider structural conditions in which local lives are lived and a precise vocabulary to describe and act on the experience of local conditions of living. Second, and more precisely, our research has taught us that landscapes of affordances and landscapes of care must be connected to improve how growing old in place can qualitatively develop. Third, we experienced a situation where the translation of our analysis into measures supporting people's activity requires a more-than-local network of actors and institutions that can use the existing experience, scale it up, and create a platform of exchange. The measures that our project identified and implemented required the orchestration of various actors and institutions at various levels: commune representatives, the cantonal health office, and an inter-communal association but also carers, social workers, associations supporting old people, and, most importantly, the old people participating in the process. Reopening a post office or a school, organising shared meals, or even offering a targeted course to use mobile phones requires the identification of needs, local offers, and opportunities and, overall, the coordination of public and private services, companies, and volunteering associations at different scales.

For both policy-makers and academics, ageing in place has become a mantra. To support the quality of life of people growing old, it is crucial to consider the totality of their living environment. Our approach aimed to deepen the idea of ageing in place, exploring it as a relational and distributed process. The notions of landscape of care and field of affordances situate the development of people growing older in their more-than-human lived environment. Our article also insists on attending to the agency and purpose of older people: how they conduct their activities and meaningful interactions in more or less liveable landscapes of affordances. If most of these landscapes of affordances emerge spontaneously with time, it does not take much to put them off balance: transformations in the environment, temporary frailty, or warmer temperatures can all have an effect. Yet, these landscapes also need to evolve to correspond to changing needs while growing older, and their evolution can, to some extent, be planned. We have argued that analysing fields of affordances requires a participatory approach to capture how an older person's daily milieu presents itself as a world of possible activities, resources, and obstacles and argued that designing a landscape of affordances requires a translational approach connecting local practices with a wider landscape of care. Importantly, our project shows that improving the life of people growing old does not require grand projects: modest interventions can support the quality of life of many – yet these interventions need to be identified, designed, and implemented with care, following a participatory and multiscalar process. We have seen that, when designed well, such participatory and translational processes take on their own momentum: not only are measures implemented successfully but a large network of social actors at different scales, from policy makers to users, are likely to become more aware of and active in the transformation of an ageing population's everyday environment.

Data are not publicly available, as the participants did not authorise their data to be used outside of this study.

Production and analysis of fieldwork material and contribution to writing – FG, AR, and IK. Design of the article and writing – OS, TZ.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

The authors would like to thank the numerous (and here anonymous) participants for their time and engagement in the project, Lysiane Mariani at the canton of Neuchâtel, and Marc Jobin at objectif.ne.

The research on which this article is based has been funded by Promotion Santé Suisse.

This paper was edited by Nadine Marquardt and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Andrews, G. and Duff, C.: Understanding the vital emergence and expression of aging: How matter comes to matter in gerontology's posthumanist turn, J. Aging Stud., 49, 46–55, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2019.04.002, 2019.

Andrews, G. J., Cutchin, M., McCracken, K., Philips, D. R., and Wiles, J. L.: Geographical gerontology: The constitution of a discipline, Social Sci. Med., 65, 151–168, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.047, 2007.

Bigonnesse, C. and Chaudhury, H.: Ageing in place processes in the neighbourhood environment: A proposed conceptual framework from a capability approach, Eur. J. Ageing, 19, 63–74, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-020-00599-y, 2022.

Bigonnesse, C., Beaulieu, M., and Garon, S.: Meaning of home in later life as a concept to understand older adults' housing needs: Results from the 7 age-friendly cities pilot project in Québec, J. Hous. Elder., 28, 357–382, https://doi.org/10.1080/02763893.2014.930367, 2014.

Bowlby, S. and McKie, L.: Care and caring: An ecological framework, Area, 51, 532–539, 2019.

Brinkmann, S.: Humanism after posthumanism: Or qualitative psychology after the “posts”, Qual. Res. Psychol., 14, 109–130, https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2017.1282568, 2017.

Butler, R. and Parr, H.: Mind and body spaces: geographies of illness, impairment and disability, Routledge, London, ISBN 0-415-17902-5, 1999.

Callon, M., Lascoumes, P., and Barthe, Y.: Acting in an Uncertain World: An Essay on Technical Democracy, MIT Press, Cambridge, ISBN 9780262515962, 2009.

Chemero, A.: An outline of a theory of affordances, Ecol. Psychol., 15, 181–195, https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326969ECO1502_5, 2003.

Conseil d'Etat: Rapport du Conseil d'Etat au Grand Conseil à l'appui d'un projet de loi portant modification de la loi de santé (LS) (Planification médico-sociale pour les personnes âgées) (12.013), Conseil d'Etat, Canton de Neuchâtel, https://www.ne.ch/autorites/GC/objets/Documents/Rapports/2021/21021_CE.pdf (last access: 7 March 2025), 2012.

Conseil d'Etat: Rapport d'information du Conseil d'Etat au Grand Conseil concernant la réalisation et les perspectives de la planification médico-sociale (15.026), Conseil d'Etat, Canton de Neuchâtel, https://www.ne.ch/autorites/gc/objets/documents/rapports/2015/15026_ce.pdf (last access: 7 March 2025), 2015.

Conseil d'Etat: Rapport du Conseil d'État au Grand Conseil à l'appui d'un projet de loi sur l'accompagnement et le soutien à domicile (LASDom) (21.021), Conseil d'Etat, Canton de Neuchâtel, https://www.ne.ch/autorites/GC/objets/Documents/Rapports/2021/21021_CE.pdf (last access: 7 March 2025), 2021.

Conseil Fédéral: Stratégie en matière de politique de la vieillesse, https://www.bsv.admin.ch/dam/bsv/fr/dokumente/fgg/berichte-vorstoesse/br-bericht-strategie-schweizerische-alterspolitik.pdf.download.pdf/strategie_en_matieredepolitiquedelavieillesse.pdf (last access: 7 March 2025), 2007.

Couturier, Y. and Audy, E.: Isolement social des personnes aînées: entre le désir de désengagement et le besoin d'un soutien concret, Gérontologie Société, 38, 125–140, 2016.

Drolet, B. C. and Lorenzi, N. M.: Translational research: Understanding the continuum from bench to bedside, Transl. Res., 157, 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trsl.2010.10.002, 2011.

Elder, G. H. and Giele, J. Z. (Eds.): The craft of life course research, Guilford Press, New York, ISBN 9781606233207, 2019.

Forsyth, A. and Molinsky, J.: What is aging in place? Confusions and contradictions, Hous. Policy Debate, 31, 181–196, https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2020.1793795, 2020.

Gfeller, F., Schoepfer, I., Ruggeri, A., Söderström, O., and Zittoun, T.: ReliÂge – Activités, ressources et obstacles pour les personnes âgées dans trois communes du canton de Neuchâtel, Université de Neuchâtel, unpublished report, 2022.

Gfeller, F., Grossen, M., Cabra, M., and Zittoun, T.: Réformes politiques face au vieillissement démographique: Diversité des perspectives dans la mise en œuvre d'une politique socio-sanitaire, Revue pluridisciplinaire d'Education par et pour les Doctorant-e-s, 1, 1, https://doi.org/10.57154/journals/red.2022.e990, 2022.

Gibson, J. J. (Ed.): The theory of affordances, in: The ecological approach to visual perception, Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale, 127–137, ISBN 9781315740218, 1986.

Grossen, M., Zittoun, T., and Baucal, A.: Learning and developing over the life-course: A sociocultural approach, Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact., 37, 100478, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2020.100478, 2022.

Levy, R., Ghisletta, P., Le Goff, J.-M., Spini, D., and Widmer, E.: Incitations for interdisciplinarity in life course research, in: Towards an Interdisciplinary Perspective on the Life Course, edited by: Levy, R., Ghisletta, P., Spini, D., and Widmer, E., Elsevier, Amsterdam, 361–391, ISBN 9780762312511, 2005.

Milligan, C. and Wiles, J.: Landscapes of care, Prog. Hum. Geogr., 34, 736–754, https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510364556, 2010.

Pani-Harreman, K. E., Bours, G. J. J. W., Zander, I., Kempen, G. I. J. M., and van Duren, J. M. A.: Definitions, key themes and aspects of `ageing in place': A scoping review, Ageing Soc., 41, 2026–2059, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20000094, 2020.

Parnell, S. and Pieterse, E.: Translational global praxis: Rethinking methods and modes of african urban research, Int. J. Urban Reg., 40, 236–246, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12278, 2016.

Power, A. and Hall, E.: Placing care in times of austerity, Soc. Cult. Geogr., 19, 303–313, 2018.

Power, E. R. and Williams, M. J.: Cities of care: A platform for urban geographical care research, Geogr. Compass, 14, e12474, https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12474, 2020.

Pratt, G., Johnston, C., and Johnson, K.: Robots and care of the ageing self: An emerging economy of loneliness, Environ Plan. A, 55, 2051–2066, 2023.

Ramstead, M. J. D., Veissière, S. P. L., and Kirmayer, L. J.: Cultural affordances: Scaffolding local worlds through shared intentionality and regimes of attention, Front. Psychol., 7, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01090, 2016.

Rogers, W. A., Ramadhani, W. A., and Harris, M. T.: Defining aging in place: The intersectionality of space, person, and time, Innov. Aging, 4, igaa036, https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igaa036, 2020.

Schwanen, T., Banister, D., and Bowling, A.: Independence and mobility in later life, Geoforum, 43, 1313–1322, 2012.

Schwiter, K., Berndt, C., and Truong, J.: Neoliberal austerity and the marketisation of elderly care, Soc. Cult. Geogr., 19, 3, https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2015.1059473, 2018.

Söderström, O.: Precarious encounters with urban life: the city/psychosis nexus beyond epidemiology and social constructivism, Geoforum, 101, 80–89, 2019.

Wiles, J. L. and Andrews, G. J.: The meanings and materialities of `home' for older people, Generations, 44, 2, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr098, 2020.

Wiles, J. L., Leibing, A., Guberman, N., Reeve, J., and Allen, R. E. S.: The meaning of “aging in place” to older people, Gerontologist, 52, 357–366, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr098, 2012.

Zittoun, T.: A sociocultural psychology of the life course to study human development, Hum. Dev., 66, 306–324, https://doi.org/10.1159/000526435, 2022.

Zittoun, T. and Baucal, A.: The relevance of a sociocultural perspective for understanding learning and development in older age, Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact., 28, 100453, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2020.100453, 2021.

See also authors suggesting an ecology of care framework articulating individual and often informal “caringscapes” with the “carescapes” of state policies and services (Bowlby and McKie, 2019) or the promotion of cities composed of various “spaces of care” (Power and Williams, 2020).

In parallel, the canton of Neuchâtel is engaged in a vast reform to support ageing in place, involving a decrease in the number of beds in full time institutions, the development of new forms of housing for older people, and other care services (Conseil d'Etat, 2012, 2015, 2021; Gfeller et al., 2022).

Names have been changed to ensure anonymity.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Ageing in place, landscapes of care, and affordances

- A participatory and translational dispositive

- Results and their translation into action plans

- Reconfiguring the landscape of affordances to support growing old in place

- Conclusion

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Ageing in place, landscapes of care, and affordances

- A participatory and translational dispositive

- Results and their translation into action plans

- Reconfiguring the landscape of affordances to support growing old in place

- Conclusion

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References