the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

“We learn Latin, they learn to cook”: students', principals', and teachers' coproductions of exclusive public secondary schools

Sara Landolt

Recent years have seen growing interest in the role of selective public secondary schools as places of state-funded privilege production. Students' experiences in and perceptions of these schools are still under-researched. Focusing on the transition to Gymnasium, highly selective public secondary schools in Zurich, this article analyses how students are addressed by principals, teachers, and education policies and how they perceive the Gymnasium and its students. Drawing on a 13-month ethnography with eight students, the article shows that students learn to see the Gymnasia as stellar schools for hard-working and intelligent students who have earned their privileges. Students play an important role in coproducing and legitimizing their privileged status in the educational field by drawing on the notion of merit. Most students distanced themselves from the non-Gymnasium “other”, labeling them as less hard-working and less intelligent. These processes ultimately contribute to a hierarchization and division of Zurich's secondary schooling landscape.

- Article

(383 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

We learn Latin and they learn how to cook. The Sekundarschule is not as hard as the Gymnasium either. It is much easier. (19_10_22_Interview)

Emil, an upper-middle-class boy that participated in our research, saw clear differences between the Gymnasium, which he attended, and the other secondary school type, the Sekundarschule. While he portrays the Gymnasium as an academically challenging school, he describes the Sekundarschule as a school that teaches more practical skills. The Gymnasium is the most prestigious secondary school track in Switzerland and the only one that grants unrestricted access to university within the public school system.1 Emil's description of the differences between the types of school hints at his impression of a somewhat divided landscape of secondary schooling in Zurich and the superior role of the Gymnasium and its students in this landscape.

Only about 20 % of students in the city of Zurich transfer to a Gymnasium after they pass a central entrance examination (CEE) (Kanton Zürich, 2022). During the first semester at the Gymnasium students are at the school on probation and have to perform sufficiently to be allowed to stay at the Gymnasium. This highly selective transition to secondary schooling is an important spatial change in students' lives (Bauer, 2018). This is when both students who transfer to these prestigious schools and those who do not pass the CEE form their images of the Gymnasium and learn about their positions in the educational landscape. This makes the transition an interesting time to study students' perceptions of these school, which is why this article focuses on this time. Moreover, it is a key moment for the reproduction of inequalities at the intersection of social class and migration background (e.g., Beck and Jäpel, 2019; Neuenschwander, 2017; SKBF, 2023): students from socioeconomically privileged backgrounds and those without migration backgrounds have higher chances of transferring to the Gymnasium than students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, even when these less-advantaged students perform equally in elementary school (Gerhard and Bayard, 2020; Moser et al., 2011).

This article presents interdisciplinary research analyzing how privilege is produced, reproduced, and legitimized in exclusive schools and how these schools and their students position themselves in the schooling landscape and broader society (e.g., Gaztambide-Fernández and Maudlin, 2015; Holt and Bowlby, 2019; Khan, 2011; Merry and Boterman, 2020; Yoon, 2016). Because most studies focus on private elite schools, highly selective public schools that provide elite education, and especially students' experiences and perceptions of these schools, are under-researched (Holt and Bowlby, 2019). Deeper insights into public elite education and students' experiences of it are important because they can help us better understand the impact of highly selective schools on young peoples' lives and their positioning in society and its role in inequality reproduction and social cohesion. Accordingly, our article furthers the research in two respects: first, it shows how students are influenced by how they are addressed by Gymnasium teachers, principals, and educational policy during the transition period from elementary school to Gymnasium and sheds light on the perspectives, perceptions, and experiences of students in exclusive public schools. This enables us to show how students in our ethnography mostly echoed how they had been addressed by the schools and described Gymnasium students as not only being academically superior. By doing so, we follow the call in the geographies of education to listen to students and to study them as subjects rather than merely as objects (Bauer and Landolt, 2018; Holloway et al., 2010; Nguyen et al., 2017).

Second, the article moves beyond the anglophone focus of the geographies of education (Henry, 2020) by adding a perspective from a country that has not widely introduced neoliberal educational policies (Steiner-Khamsi, 2006). Switzerland never implemented high-stakes testing, nor does it publish performance reports for individual schools to increase competition, and it generally has well-financed urban public schools with good reputations. Against this backdrop, we consider Zurich's Gymnasia a promising field to explore exclusive public schools as places of state-funded privilege production, as especially in Switzerland, the Gymnasium has rarely been studied as a public elite school.

Conceptually, this article is inspired by Bourdieu's work on cultural reproduction and education (Bourdieu, 1973, 2018) and his concept of capital and field (Bourdieu, 1977, 1986). Using a Bourdieusian framework helps to illuminate both the production of symbolic capital at the Gymnasia and how students' belief in meritocracy is relevant to their positioning in Zurich's student body and their self-understanding. The article builds on a 13-month ethnography, including participant observations and interviews with eight children (11–13 years old) at the transition to Gymnasium and in-depth interviews with relevant actors in the field. This allows us to shift attention to the students' perspective while also analyzing the addressing of the students, which influences their experiences and perceptions. We investigated two interrelated questions to gain new insight into state-funded privilege production at public schools in a non-anglophone context. (i) How are students addressed by Gymnasia teachers, principals, and educational policy during the transition period, and how are the Gymnasia presented? (ii) How do students experience and perceive the Gymnasia and their position within the field of secondary education in Zurich during the transition period?

We begin this article by reviewing the interdisciplinary literature on educational inequalities and public and private elite education and introducing the theoretical framework of the analysis, followed by a description of secondary education in the city of Zurich. We then elaborate on our methods and data before turning to our findings in the fifth and sixth sections. We end with a discussion and suggestions for future research.

Geographers and sociologists have studied schools as places where inequalities are perpetuated and class advantage and privilege are constructed, maintained, and legitimized (e.g., Hafner et al., 2022; Holloway and Pimlott-Wilson, 2019; Koh and Kenway, 2016; Kuyvenhoven and Boterman, 2021; Lipman, 2007; Reay et al., 2011). The geographies of education research contributed to this field, particularly by studying students' identity construction in schools (e.g., Davidson, 2008; Holt and Bowlby, 2019) and unequal educational chances in stratified public school systems (e.g., Boterman, 2019; Butler and Hamnett, 2012; Wilson and Bridge, 2019). One increasingly discussed driver of inequalities and privilege reproduction in stratified public school systems is highly selective and elitist public secondary schools (e.g., Gamsu, 2018; Merry and Boterman, 2020; Parekh and Gaztambide-Fernández, 2017).

The focus of studies on elite education has long been on private boarding schools that, while becoming more diverse, still predominantly educate the financial elite (e.g., Gaztambide-Fernández, 2009; Khan, 2011). Recent years have seen a shift towards understanding the elite as more complex and fluid, including “new elites” who have parents with low socioeconomic status (Harvey and Maclean, 2008; Savage and Williams, 2008). This has also resulted in an important new subfield in the studies of elite education: a small number of studies have focused on analyzing highly selective public schools, some of them boarding schools, that offer academically more demanding educational programs and more extracurricular activities as a form of state-funded elite education (e.g., Gamsu, 2018; Gibson, 2019; Holt and Bowlby, 2019; Merry and Boterman, 2020; Persson, 2021; Yoon, 2016). In contrast to private elite schools, selective public schools are not financially exclusive because they do not charge tuition. They often strongly emphasize their meritocratic character because they select their students by academic achievement and distance themselves from the financial elite (Helsper et al., 2014; Persson, 2021). But despite public elite schools' financial inclusiveness and their importance to “recruitment into the elite class” through achievement (Savage, 2015:324), they have been shown not to be particularly diverse in their students' ethnicity or socioeconomic background (Halvorsen, 2022; Yoon, 2016). This results from upper-middle-class parents using their economic and cultural capital to help their children gain entry to these schools (Boterman, 2019; Butler et al., 2013; Reh and Landolt, 2024).

Schools are places that legitimize unequal power relations, strongly influence the students' identity formation, and teach them about their place in society (Nguyen et al., 2017). Consequently, it is crucial to deepen the understanding of students' experiences and perspectives in elitist public schools as their students are likely to have powerful positions later in life. Student experiences in elite private schools are well researched (e.g., Khan, 2011; Khan and Jerolmack, 2013; Lillie, 2020; Taylor, 2021). Khan (2011) applied Bourdieu's theory of capital and habitus in his ethnography of an elite boarding school in the US. The ethnography shows how students have to acquire the embodied skills of ease through interactions at this school to perform elite status and privilege and to position themselves as a meritocratically legitimized elite and not one that inherited their status.

In contrast, questions of how students experience and interpret classed educational landscapes and exclusive public schools are understudied (Holt and Bowlby, 2019). Among the few researchers who have focused on exclusive public schools from students' perspectives are Louise Holt and Sophie Bowlby, who examined the experiences of girls in a public elite British grammar school to provide insights into how classed privilege is reproduced in public schools. They show how the girls they studied developed a sense of belonging in the school both by othering non-grammar-school students and by classed, gendered, and ethnicized performances as hard-working, successful, and polite students (Holt and Bowlby, 2019).

The exclusion and separation processes of elite educational institutions and the role they play in legitimizing elites' leadership status were described by Bourdieu (1996) in his study on the “production of nobility” at elite universities in the UK, the US, and France. He writes that “the process of transformation accomplished at `elite schools,' through the magical operations of separation and aggregation … tends to produce … an elite that is not only distinct and separate, but also recognized by others and by itself as worthy of being so” (Bourdieu, 1996:102). Educational institutions legitimize inequalities and the reproduction of the elite by interpreting societally determined differences in abilities such as linguistic skills as differences in talent (Bourdieu, 2018:31). Bourdieu was writing about educational institutions several decades ago, but the legitimization of elite status and privileges through ostensibly merit-based educational systems is also evident today in elitist public schools in various countries (Phillippo et al., 2021; Törnqvist, 2019). For example, Törnqvist (2019) showed how exclusiveness and privilege production at a public secondary school in Sweden are shaped, legitimized, and disguised by an individualized meritocratic discourse and the downplaying of the students' socioeconomic backgrounds. This rendered the elite character of the public school compatible with the ethics of an egalitarian school system, thus highlighting how privilege can also be fostered in public schools in a seemingly egalitarian school landscape (Törnqvist, 2019:564).

Bourdieu's writings and his notion that cultural reproduction through education is fundamental to the reproduction of class-based inequalities have had a lasting influence on research on educational inequalities, including in the geographies of education (Blokland, 2023; Holloway et al., 2024). This article draws on Bourdieu's theory of cultural reproduction and the legitimization of inequalities through educational institutions (Bourdieu, 1973, 2018) and his conceptualizations of capital and field (Bourdieu, 1977, 1986) to illuminate Gymnasium actors' distinction-making and “symbolic domination” over non-Gymnasium others in the field of secondary education in Zurich. The concept of field represents the multidimensional social space in which individuals are differentially positioned depending on their capital: their economic capital such as money; their social capital, which is their durable networks; their cultural capital, which may be embodied, such as language skills, and institutionalized, such as diplomas; and their symbolic capital, which is the distinction and prestige that result from the other forms of capital being perceived as legitimate (Bourdieu, 1986). In the field of school education in Zurich, actors come together with differing levels of cultural, social and economic capital, which influence their ability to act and position themselves in this field. Symbolic domination is another important field-theoretical concept that sheds light on how power relations and consequent dominance in the field are subjectivized and naturalized, influencing where dominated agents feel “the sense of their place” (Bourdieu, 1985:728). Students adopt the system's assessment and attribute their failure in selection exams not to the system but to their own performance: the system therefore not only selects but also convinces those selected that they themselves are responsible for their elimination (Bourdieu, 2001:21)

The research mentioned above provides insight into how privileged public and private schools contribute to the perpetuation and production of privilege. However, questions remain unanswered regarding students' experiences and perceptions and their role in producing and reproducing privilege and symbolic capital (not only) during the transition to exclusive public schools (one exception is Phillippo, 2019). This article addresses these questions by studying distinction-making and privilege production during the transition period to Gymnasium in Zurich and the students' perceptions of and role in these processes. This article focuses on the transition period as the educational experience of competitive school choice has been shown to be “civic lessons” that teach students about societal differences and different positions, the field of education, and their place in it (Phillippo et al., 2021). Furthermore, it is the time when students form their first impression and image of the Gymnasia.

In Zurich, students are divided into different secondary school tracks after elementary school, which finishes with sixth grade at around age 12. After sixth grade, about 80 % of students transfer to Sekundarschule with no formal assessment; there, they are tracked into two or three academic levels. Students with good school grades mainly sign up for the central entrance examination (CEE) for the academically most demanding secondary school type, Gymnasium (grades 7 to 12). In the city of Zurich about 55 % of students writing the CEE pass it (Kanton Zürich, 2024a). Those who do not pass cannot attend the public Gymnasium but have to transfer to Sekundarschule. The Gymnasium is usually followed by a tertiary education pathway. The Sekundarschule lasts 3 years (grades 7 to 9). Afterwards, most Sekundarschule students start a multiyear vocational education and training (VET) (SKBF, 2023), but a few Sekundarschule students take another CEE to transfer to a 4-year Gymnasium that finishes with the same qualification, the Matura, as the 6-year Gymnasium, which is the focus of this article. Both grant unrestricted access to university. Overall, 21.8 % of the student population in the city of Zurich obtained an academic Matura (gymnasiale Matura) in 2021 (Kanton Zürich, 2024b). Students with a VET also have the possibility to obtain a vocational Matura which grants access to tertiary education at universities of applied sciences or a vocational tertiary education (höhere Berufsausbildung).

The high competition for admission to public Gymnasia in Zurich is strongly influenced by the city's growing population and thriving economy, which results in a high proportion of residents with either vocational tertiary degrees or degrees from universities or universities of applied sciences (56 %) (Stadt Zürich, 2023) and a foreign-born population of roughly 33 % (Stadt Zürich, 2022). This combination has a strong impact on the high competition for Gymnasium places for two reasons: firstly, parents with tertiary education are interested in maintaining their status and therefore want their children to transfer to Gymnasium to be able to attend university (Cattaneo and Wolter, 2016). Secondly, first-generation foreigners in Switzerland prefer an academic education over a VET and tend not to value the labor market outcomes of vocational education (Abrassart et al., 2020). Both factors intensify the competition for Gymnasium places, as the transition rate from elementary school has remained constant at around 20 % in the canton of Zurich since the 2000s (Criblez, 2014; Pfister, 2022).

The children and their families have to choose which Gymnasium they want to attend when registering for the CEE of their choice. There is no possibility to state a second or third choice. This is the only instance in Zurich's school system when a school choice is mandatory as all Sekundarschulen and all elementary schools are catchment-based schools. All Gymnasia offer the same curriculum in the first 2 years, including compulsory Latin lessons. However, there are minimal differences between the Gymnasia such as one lesson more or less in the sciences. Furthermore, the six Gymnasia differ in terms of location (three of the six Gymnasia are in the privileged Zürichberg neighborhood, while the other three are in other parts of the city) and size (ranging from 700 to 2000 students). Gymnasia in Zurich are not ranked, and no performance reports or average Matura grades are publicly available, which makes the Zurich case different from other cities such as Chicago, which has implemented education reforms that put schools into direct performance competition (see, e.g., Phillippo, 2019). Besides the public Gymnasia, there are also a few private Gymnasia in Zurich, which charge relatively high tuition fees. Public Gymnasia have a good reputation in Zurich, and private Gymnasia tend to be seen as a second-best option for children who did not pass the CEE for the public Gymnasia.

There are considerable differences between the seven urban school districts in Zurich in transfer rates from elementary school to Gymnasium because socioeconomic inequalities are reproduced at this transition and the school districts vary in their socioeconomic makeup due to residential segregation in the city. The most privileged district, with the lowest percentage of social aid recipients and German-as-second-language students and the highest income level, has a transfer rate to Gymnasium that is more than 3 times higher than that of the least privileged district (Kanton Zürich, 2022). Students with a migration background and those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged are underrepresented at all Gymnasia in Zurich, but the Gymnasia's diversity varies in the migration background of their students (Gerhard and Bayard, 2020). The few existing qualitative studies that analyze how inequalities are reproduced at the transition to secondary schooling in Zurich and other cantons indicate that the parents' cultural and economic capital and their ability to support their children (Bauer and Landolt, 2022; Reh and Landolt, 2024) and the teachers' assessment and grading, which are sometimes biased by the students' social class, are important (Hofstetter, 2017; Streckeisen et al., 2007).

This article draws on a 13-month ethnography conducted by Carlotta Reh. The ethnography consisted of participant observations, spontaneous ethnographic interviews, the collection of documents, and recorded in-depth interviews. Conducting interviews with actors in Gymnasium education in Zurich allows us to capture the “nexus of doings and sayings” (Schatzki, 1996) and to conduct an in-depth empirical analysis of the relation of the students', parents', teachers', and principals' practices and narrative accounts. The interview situation reflects these differently from observing the actors in conversation with their peers or in everyday life and complements the participant observations.

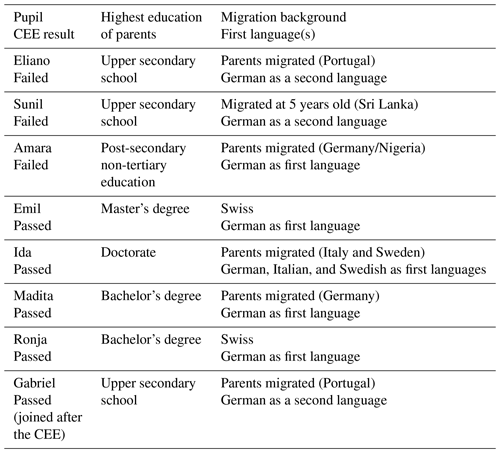

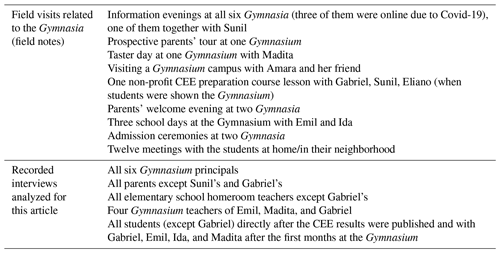

The participant observations were conducted with eight students who were at the transition to Gymnasium and their families, teachers, and classmates (see Table A1). Four of those students passed the CEE and transferred to a Gymnasium after the summer. One student did not want to continue in the study after the CEE (Ronja). As this meant that only three student participants would transfer to Gymnasium, another student who had passed the CEE and whom Carlotta Reh knew already through Sunil and Eliano joined after the CEE (Gabriel). The students came from diverse socioeconomic and migration backgrounds, included both males and females, and attended different elementary schools across the city. The participants were recruited through elementary schools and a private nonprofit initiative that prepares disadvantaged students for the CEE. The participants were observed at multiple locations, including lessons at elementary schools and Gymnasia, hanging out with their friends outside of school, and at school-choice-related events such as information evenings and taster days. The data were collected during the whole transition period, starting in October 2021 with the start of the school choice events and the students' CEE preparation during sixth grade and finishing in November 2022 after the first months at Gymnasium. Participant observations lasted between 1 and 4 h each. Carlotta mostly became a “participant-as-observer” (Gold, 1958): they were known as an observing researcher to the students and their friends and siblings while still being largely integrated in the field and included in the classroom and family life, for instance when students approached them for help during classes or joining a family dinner. The analysis presented in this article focuses on the school choice period and the first moments and months at the Gymnasia and included those field notes produced at 30 participant observations at the Gymnasia or the students' homes during their first weeks at the Gymnasia and some of the field notes taken at their home during the school choice period (see Table A2 for an overview of the data included for the analysis for this article). By focusing on the transition period, we can show how Gymnasium staff construct their schools as exclusive and how they address students during the transition and how students experience and perceive the Gymnasia and their position within the field of secondary education in Zurich during this time.

Moreover, the ethnographic data set includes 36 transcripts from semi-structured interviews with various actors that were involved in the transition: principals of all six public Gymnasia in Zurich starting after elementary school, a few of the students' Gymnasium teachers, all their elementary school teachers, and most students' parents. Furthermore, episodic interviews (Flick, 2019) with the students themselves were conducted twice: once in sixth grade after the CEE results were sent out and once in seventh grade after the first 2 months at Gymnasium to discuss their first weeks there. All interviews sought to understand how the participants talked about the Gymnasium and its students and their perceptions on questions of inequalities and merit at the transition to Gymnasium. All participants and their legal guardians gave their written consent to participate in the study.

For this article, all interview transcripts and field notes were open-coded with a focus on exclusion and privilege production following Charmaz's (2006) grounded theory approach. Afterwards, key themes and patterns were identified. These included both conceptual themes from the literature and our research questions and “in vivo themes” emerging from the data (Charmaz, 2006).

During the transition period, the Gymnasia's teachers and principals present the Gymnasia to prospective students at various events and in the first weeks at the Gymnasium and in doing so position the Gymnasia in the field of secondary schooling in Zurich.

5.1 The best and the brightest

Sunil and Carlotta attended an information event by Pilatus Gymnasium on a November evening. Sunil, a boy from a disadvantaged socioeconomic background with German as his second language, was already slightly bored after a rather dry description of the differences between the Sekundarschule and the Gymnasium at the beginning of the event. However, when the principal started to talk about the right students for the Gymnasium and emphasized that it was not a school for everyone, he started to focus on the principal and seemed to listen more actively. The principal portrayed the ideal Gymnasium student, describing them as “gifted”, “highly interested and curious”, and “hard-working”. These and similar portrayals of the typical Gymi-Kind (child at a Gymnasium) were dominant at the information sessions and the taster days of the Gymnasia. The addressing of the students as talented Gymi-Kinder was also conspicuous in the first weeks at the Gymnasium. In a lesson in the second week at the Gymnasium in Ida's class, students were asked to raise their current concerns with the school work. One boy spoke up:

Leo says that he never had to do homework in elementary school because he had always finished everything in class and now he has to get used to doing homework. The class teacher nods and says: “You were all the best in your elementary schools, now you have to get used to work harder for school”. (01_09_22_Fieldnotes)

The collective narrative of the Gymi-Kind serves as a constant confirmation of the excellence of the Gymnasium students and their positive character traits. It functions as legitimization and naturalization of the Gymnasium and its students' privileges (Bourdieu, 2018). The students have been publicly recognized as merit-based academic elite students by teachers, principals, and students in the competitive school system in Zurich, which gives them a superior status. Amara's elementary school homeroom teacher reinforced the image of the very intelligent Gymnasium student in front of her students in the classroom but later criticized the Gymnasium students' status in an interview:

I don't think it's good what kind of status is made of it. So that the Gymnasium students have the status of being the best and clever ones. (21_12_21_Interview)2

This image of the Gymnasium and the addressing of its prospective students as academically elite is ostensibly justified by the selection of the students through a combination of students' grades in sixth grade, their results in the CEE, and a semester-long probation period. This allows the Gymnasia to position themselves and their students as a meritocratic and academic “elite”, reinforcing the accumulation of symbolic capital of Gymnasium students (Bourdieu, 1986). The students are taught through this form of address that their privileges, such as being able to choose a school and having more specialized teaching rooms such as labs and teachers that are experts in their subjects,3 are earned and that they deserve to be treated differently. This is mirrored in the observation that the term “elite” is frowned upon by Gymnasium staff. Teachers and principals would rather choose terms such as “gifted” and “the best and brightest”, and they made sure to distance themselves from an elite with high volumes of economic capital. Similar observations have been made in the egalitarian Nordic countries and Germany, where elitism has a rather negative connotation (see Halvorsen, 2022; Helsper et al., 2014; Törnqvist, 2019). Only one teacher at Pilatus Gymnasium called the Gymnasium an “elite institution”, but she clearly stated that she referred to a meritocratic elite of cultural capital and educational achievement:

I simply believe that the Gymnasium is and should remain an elite institution. Elite not in the sense of “the most money” or “the most family history” or whatever, but elite in the sense of really the most talented and also the most motivated students. (12_09_22_Interview)

Another facet of the Gymnasia addressing the students during the transition is the vision of successful futures that is presented at the admission ceremonies and information evenings (see Gaztambide-Fernández, 2009). Students were repeatedly addressed by principals and teachers as future university students and specifically as students at the public elite university ETH Zurich, as future doctors and lawyers, and hence as people who are prepared for leadership positions. Despite the highly regarded Swiss education system with multiyear VET, the institutionalized cultural capital that comes with a university education is an important prerequisite to becoming part of the upper-middle class and elite in Switzerland (Pfister, 2022). In their speech at the admission ceremony for the new seventh graders, which started with students performing the song “9 to 5” and ending it with the statement that at the Gymnasium students would rather need to work from 9 to 7, the principal of Matterhorn Gymnasium talked about the students' future:

The principal goes on to say that our world needs young people who will ask questions, who will discuss ideas and who are curious. The students will have the chance to make the world a better place and here at Matterhorn Gymnasium they will be given the tools to do so. (22_08_22_Fieldnotes)

Addressing the aspiring Gymnasium students as future university students who have the power to change the world for the better and the Gymnasium as the school that prepares them for this future was common during the transition period.

5.2 Stellar schools of choice – addressing through educational policy

The second important aspect of how students are addressed during the transition period is the addressing through educational policy, more precisely the organization of the transition to secondary schooling in the city of Zurich. There is a free choice for the selective Gymnasia but not for the Sekundarschulen because these are catchment-based schools, which means that student attend the Sekundarschule in their catchment area. This difference, as well as the above-mentioned differences in teacher salaries and teacher education and the differences in the schools' facilities and equipment, is grounded in the specific organization of the education system in Switzerland. While the Gymnasia are governed and financed by the respective cantons (in this case the canton of Zurich), the elementary schools and the Sekundarschulen are managed and funded by the municipalities, in this case the city of Zurich.

The differing school choice and transition policies for the Sekundarschule and the Gymnasium result in marketing events for parents and students but only for the Gymnasia. These events include information evenings with image films, parent school tours during which senior students show parents around campus, and taster days where prospective students have taster lessons and receive merchandizing material such as stickers and pencils. Each year, at least twice as many students as there are places apply at all Gymnasia. Furthermore, the Gymnasia do not compete for the students with the highest grades: if more students pass the CEE at a Gymnasium than the school has places, some students are redistributed to other Gymnasia. However, the Gymnasium with the highest demand is not allowed to select those students who have the highest CEE results but must select students based on their residential proximity to the school. Hence, marketing them is not necessary. But Gymnasia use the school choice policy to host marketing events at which they construct and present themselves as stellar institutions with outstanding amenities and interesting and diverse extracurricular activities which differentiate them from the Sekundarschule and add to their desirability and prestige. One Gymnasium even had a dedicated website for prospective students to promote itself:

Technology is in the air everywhere in the building. Well, your free iPad, which you get during the probation period, doesn't look particularly unique. But the special chemistry and physics labs and the Makerspace, our workshop for electronics and robotics, create an exciting technical-scientific atmosphere. (https://schnuppertag-hopro.ch/cms/, last access: 23 October 2024)

The fact that marketing events during the transition period take place only for the selective Gymnasia also addresses the sixth graders and teaches students about deservedness and importance. Only the students aspiring to attend the academically more challenging Gymnasia are solicited; have a day off from elementary school to attend taster days, which makes the different treatment of students at this transition very visible in the classroom; and can choose a Gymnasium.

Emil's father, who partly grew up in the United States and attended a prestigious public university there, compared the Gymnasium promotion events to those of universities in the US and hence compared tuition-free public Gymnasia to educational institutions charging high tuition fees. He said,

these image films of the Gymnasia, I think I've said this before, are like these advertising videos for university or college, and the taster day for the Gymi, like in the US for college, is very similar. I was surprised this was even offered. (07_01_22_Interview)

These marketing events and other promotions potentially make the Gymnasia even more desirable than the Sekundarschulen. This in return awards the students who attend Gymnasia or try to transfer there with symbolic capital. The prospective students that are solicited by the Gymnasia can develop a strong identification with the Gymnasium even during the school choice process. Emil attended taster days at two Gymnasia and info events at three. When he came home from the taster day at Matterhorn Gymnasium, he had made his decision. His mother described the following in an interview: “After that taster day, he was absolutely thrilled with Matterhorn Gymnasium, so he came home and put a sticker on his bedroom door that said `I love MG' [laughs]” (07_01_22_Interview). Stickers like this do not even exist for Sekundarschulen. This results in a division between the Sekundarschulen and the Gymnasia and their students in the city of Zurich because they are treated and addressed very differently during the transition process and are given very different degrees of decisive power and possibilities to identify with and be proud of their Gymnasia.

How they are addressed affects how prospective Gymnasium students experience and perceive the Gymnasium and its students and thus their own positions in the field of secondary schooling. In this section, we demonstrate how students understand themselves as a merit-based academic elite during the transition, how some students challenged this conception, and how they perceive and coproduce the secondary school landscape as divided and hierarchized.

6.1 The academic elite

When the sixth graders discussed the Gymnasium among their peers or with Carlotta, they usually emphasized that the Gymnasium is theoretical and academically more demanding, just as Emil elaborated in the opening quotation. Students often highlighted that this is where students learn a classical language instead of having more practical subjects such as “learning how to work,” as Eliano called it (the subject's name is economy, work, and housekeeping). Learning Latin can still be understood as cultural capital and a marker of affiliation to a cultural elite (Sawert, 2018), and it indicated to the students that Gymnasia are the schools for the smarter children.

But it was not only by subjects that the Sekundarschule was contrasted with the Gymnasium by prospective Gymnasium students. They also often employed descriptions of Sekundarschule students as counterparts from which they clearly distanced themselves; a similar abjection of the non-grammar-school others has been described by Holt and Bowlby (2019). Ronja, a student with a middle-class background, emphasized shortly after she passed the CEE that “at the Sekundarschule, it's usually the rougher kids who are somehow super cool, and at the Gymi it's always the ones who want to focus on learning” (31_03_22_Interview). Emil, an upper-middle-class boy, after he had passed the CEE even declared that “there are always idiots like that, and they're all going to Sekundarschule now, and I'm going to Gymi” (24_03_22_Interview). Overall, the Sekundarschule students were often described as the opposite of the hardworking, motivated, and curious Gymi student by those attending or planning to attend the Gymnasium. The participants gave themselves, Gymnasium students, a higher value when they described Gymnasium students with many positive attributes and Sekundarschule students with rather negative ones.

These short insights from Ronja and Emil show how students at this selective transition may categorize their classmates and themselves into groups with differing symbolic capital. In our research project, we focused on adolescents who aspired to go to Gymnasium and therefore cannot make any statements about how this transition is perceived by students who do not try to transfer to Gymnasium. Nevertheless, our data show that the design of the transition and the way in which the Gymnasia and elementary school teachers address students during this process can lead to a clear hierarchization of Zurich's students in the eyes of Gymnasium students, who position themselves at the top of this hierarchy.

The students in our ethnography mostly echoed how they had been addressed by the Gymnasia in the transition period and described Gymnasium students as the smartest ones. Amara, a working-class girl who did not pass the CEE, described the “right” students for the Gymnasium in an interview after the results of the CEE had been released:

You should be above the average, yes, so if you're an average kid, then rather not, if you're more gifted, then you can give it a try. [It is] a school for the particularly intelligent, so to speak. (23_03_22_Interview)

But Eliano's case indicates that students who did not pass the CEE might change their perception of the Gymnasium after they receive their negative CEE result. At the beginning of the transition period, Eliano, a boy from a disadvantaged socioeconomic background with German as a second language, had also told Carlotta that the Gymnasium was for the brightest and best students. When Carlotta talked to him about his school choice during a visit at his elementary school early in the transition period, he seemed to have had an intuition that it was harder for him as a non-Swiss child to obtain a place at the Gymnasium. He mentioned that the Pilatus Gymnasium was his choice because, according to his teacher, it is attended by more foreigners like him (08_11_21_Fieldnotes). After the CEE results were released, he noted that one socially marginalized group is disadvantaged at the Gymnasium:

Carlotta: What would you say, what kind of students go to Gymnasium, who is “the right one” for it?

Eliano: Maybe not the foreigners who don't speak German so well, they won't make it. (29_03_22_Interview)

After the CEE, he began seeing the Gymnasium as a place that can exclude non-native speakers like him, who did not pass the CEE due to their low grade in the German exam despite their hard work and their high performance in math. He experienced a devaluation of his abilities and achievements and seemed to adopt the dominant view of students whose native language is not German as not being good enough for the Gymnasium (Bourdieu, 1985). His “feeling out of place” at the Gymnasium is a case of misrecognition that creates insecurities (Bourdieu, 1999). Students might actually experience the Gymnasium as a school that is not for foreigners' children who do not speak German as their first language, such as Eliano, who was born in Switzerland to Portuguese parents and hence had no Swiss nationality. The information events and the CEE registration site are only available in German, and the CEE comprises two challenging German exams as part of the CEE. Language-based inequalities and disadvantages at the transition were frequently discussed in Zurich's elementary schools (see Reh and Landolt, 2024). Ronja, a Swiss middle-class girl who passed the CEE at Rigi Gymnasium, also questioned whether the transition actually selects the most hard-working and intelligent students. She mentioned that students who do not speak German so well should get a modified exam; one friend of hers did not pass the CEE because she spoke German as her second language (31_03_22_Interview).

6.2 Being important, deserving, and superior in a divided secondary school landscape

Few students challenged the narrative of the Gymnasium as a merit-based school for the brightest and most hard-working students as Eliano cautiously did. Most of the students in our ethnography who aspired to attend Gymnasium echoed the narrative of a meritocratic academic elite that earned and deserved its privileges due to hard work and intelligence. The students thus played a role in coproducing this legitimization of state-funded privilege production at the Gymnasia. When Emil, a student at Piz Bernina Gymnasium, talked about better amenities such as larger laboratories and libraries at Gymnasia than at Sekundarschulen, he explained that

the Gymi students deserve it because they wrote the Gymi exam and they passed and I don't want to look down on them [the Sekundarschule students], but I actually do. … So, it's like hard-earned, yeah. … So, the Gymnasium students have [learned] half a year or maybe two years or six years for it, have prepared themselves, and it is just very deserved. (18_10_22_Interview)

Emil sees himself as deserving to have better amenities because he worked hard and passed the entrance exam, using the ostensibly merit-based admission to legitimize his privilege (see Halvorsen, 2022; Törnqvist, 2019). He also exhibits a certain feeling of superiority over non-Gymnasium students. Using Bourdieu's understanding of field, we suggest that the students' perceptions of the Gymnasium as a largely meritocratic school for the academic elite generates an understanding of their position in the hierarchical social space, as Emil's quotation illustrates. In an interview directly after he had received the information that he had passed the CEE, he told Carlotta that “many want to go to the Gymi, but few make it” (24_03_22_Interview). These feelings of accomplishment and deservedness were strengthened by the admission ceremonies that the Gymnasia hold for their new students. Such admission ceremonies do not exist at the Sekundarschulen. The ceremonies at the Gymnasia are often attended by parents who take half a day off of work and sometimes even grandparents who travel to Zurich from abroad (22_08_22_Fieldnotes). Gabriel, a boy from a socioeconomically disadvantaged migrant background, described the Pilatus Gymnasium ceremony as follows:

There was the ceremony, the admission ceremony, we were in the church and there was a choir that sang for us. Afterwards, the principal got to know us, so we got to know the principal. The parents were all there too and sat upstairs. It was really cool. (03_11_22_Interview)

These ceremonies, sometimes held in the Gymnasium's auditorium, sometimes in churches nearby to provide more room for students' family members, were pregnant with meaning and made students feel important. They also learned to feel deserving. The ceremonies welcomed the students and also celebrated their admission into the privileged group of Gymnasium students. It was another event at which students learned to be proud of their achievements and of the venerable institution they now attended.

The students' perception of the Gymnasium at the time of transition and their position as Gymnasium students also depends on their future aspirations and the understanding of which future paths the Gymnasium enables them to pursue. Students experience the transition as a crucial point in their life at which their future group membership and their potential for distinction are decided. Although a second opportunity to transition to Gymnasium arises after Sekundarschule, many students in our ethnography talked of VET as the only possible future after the Sekundarschule; even before they attend Gymnasium themselves. Madita, an upper-middle-class student, explained shortly after she was informed that she passed the CEE that

the Gymnasium allows you to do more things, you can go to university, and at the Sekundarschule, you can only do an apprenticeship. (22_03_22_Interview)

The Matura, which enables direct entry to university, is seen as a prerequisite for a brighter and more successful future by most students aspiring to transfer to Gymnasium. Gabriel stated that

I wanted to go to Gymnasium so that I could develop further, so that I could go deeper into subjects, so that I would have more opportunities in life in the future. (03_11_22_Interview)

The belief that the Gymnasium offers the best education and the brightest future is shared by most aspiring students in our ethnography, especially those who have a disadvantaged migrant background (see Abrassart et al., 2020). They see the Gymnasium as a chance for social upward mobility. Often, only the academic path via Gymnasium is viewed as success by Gymnasium students. This furthers their coproduction of their superior status as they devalue the nonacademic paths and hierarchize students and their future ambitions and possibilities.

This division and hierarchization of the field of secondary schooling also influence the students' friendships that they formed in elementary school and in their neighborhoods. Ida, a middle-class student at Piz Bernina Gymnasium, still occasionally meets with friends who transferred to Sekundarschule. She described a scene in her neighborhood's youth club that illustrates how the hierarchization of the student body influenced her friendship. She said,

the other day I met friends who are at Sekundarschule. … At the youth club, there was someone who asked, are you all in the Sek, and my friends were like, yes, except for her, pointing at me, she's the super smart one and is in Gymi. I generally have the feeling that maybe they have a bit of a feeling that they're not as good as us. (26_10_22_Interview)

Ida was named by her Sekundarschule friends as being “the smart one”, but later in the interview she questioned whether she is generally smarter than them. She still clearly refers to “us”, the Gymnasium students, and “them”, the Sekundarschule students, and thus reproduces a certain divide. Gabriel and Emil, who also transferred to Gymnasium, said that they no longer have much contact with their friends who transferred to Sekundarschule due to their workload, different timetables, and new friends at the Gymnasium. This shows how the hierarchization of the educational landscape and the addressing of students at the transition influence the students' personal relations with each other. It might indicate how the “world of the Gymnasium,” as the Pizol Gymnasium principal called it, and the “world of the Sekundarschule” drift apart, resulting in fewer contact points between their students and potentially dwindling social cohesion.

This article's first aim was to show how teachers, principals, and educational policy address students during the transition period and to shed light on the under-researched perspectives of students and their perceptions of exclusive public schools, which are influenced by such addressing. The article makes two contributions. First, it demonstrates how students at the transition period are strongly addressed as the merit-based academic elite that deserves to be treated differently from the majority of students and that students' perception of the Gymnasia and their position in Zurich's landscape of secondary schooling mostly echoes this addressing. The article argues that students learn to see themselves as deserving, academically superior, and valued through both verbal addresses by teachers and principals and an address by educational policies during the transition period. In this period, the Gymnasia are presented as stellar schools for intelligent, hard-working students, which gives them and their students a superior status. This also contributes to a divided and hierarchized field of secondary education in Zurich with the Gymnasium as the superior option and, in the perception of the children, a route to a successful future with more opportunities. Gamsu (2018) described a similarly hierarchized field of schooling in London, where elitist “super-state schools” (Gamsu, 2018:1171) dominate the field and allow both state-funded upward social mobility and social reproduction. But whereas the grammar school he studied largely mobilized traditional forms of cultural capital, mimicking British elitist private schools, Zurich's Gymnasia do not mimic private schools; the public Gymnasia have a very good reputation but distinguish themselves from other school types by the different future possibilities they offer and the high academic selectivity.

Second, the article demonstrates the students' agency in creating and legitimizing the status of the Gymnasium and its students but also in potentially challenging it. During the transition period, they receive distinction as academically elite and hard-working through the acquisition of certain types of symbolic and cultural capital (Bourdieu, 1986). In this time, they actively distinguish themselves by coproducing particular images and prejudices about Sekundarschule students and Gymnasium students and thus contribute to the production of the distinction and symbolic capital associated with attending Gymnasium. Students play a role in creating an image of Gymnasium students as the best, brightest, and most hard-working ones who deserve privileged school spaces and treatment (see Yoon, 2016; Phillippo et al., 2021). Most of the students who passed the CEE and attended Gymnasium after the summer also clearly distanced themselves from the non-Gymnasium others, often stigmatizing them as being less intelligent and interested (see Holt and Bowlby, 2019). Thus, they play an active role in legitimizing their positions as students with privileges that later enable them, for example, to obtain a university degree. The hierarchization of Zurich's field of schooling that the aspiring Gymnasium students coproduce potentially results in local forms of “symbolic domination” (Bourdieu, 1985) of Zurich's non-Gymnasium students. This can influence who feels a sense of belonging at the Gymnasium, as Eliano's case showed; he perceived the Gymnasium as a place that is not for “foreigners' children” like him with German as a second language.

The article's second aim was to add a perspective from a country that did not widely introduce neoliberal educational policies and thus to move beyond the anglophone focus of the geographies of education (Henry, 2020). Our research has shown the importance of the local and national contexts in how Zurich's educational policies contribute to the students' perception of their privileged schools. But the students' self-understanding as being especially smart and hard-working and their positioning as being superior and academically elite resonate with findings from more market-oriented educational systems at elite public grammar schools in England (Holt and Bowlby, 2019), highly selective magnet schools in Chicago (Phillippo et al., 2021), and highly selective “mini high schools” in Vancouver (Yoon, 2016). Rather than feeling that they are entitled elites (Gaztambide-Fernández, 2009), students mobilize a meritocratic ideal and root their privilege in the understanding that they are the highest-performing students in their city or area. Principals and teachers similarly avoid the “elite” label for their Gymnasia and emphasize their meritocratic nature to legitimize their special status. This corresponds to research in other countries with less-neoliberal educational policies such as Sweden (Törnqvist, 2019), where schools have to position themselves in a discourse field of elitism and egalitarianism.

It would be interesting to investigate more thoroughly how students from disadvantaged backgrounds, both low socioeconomic status and migration background, perceive and experience exclusive and elitist public school spaces in the years following the transition period. The only disadvantaged student in our sample that passed the CEE and transferred to a Gymnasium was Gabriel (who only joined the ethnography after the CEE, as no other student from a disadvantaged background had passed); this exemplifies the underrepresentation of such students at these Gymnasia. Eliano, who aspired to attend the Gymnasium but did not pass the CEE, had the feeling that the Gymnasium was not a welcoming place for him as a non-Swiss student with German as a second language. Gabriel's case indicates that such factors as the social capital children have acquired in elementary school (e.g., friends who transfer to Gymnasium with them), which depends on the socioeconomic composition of their school and its transfer rate to Gymnasium, might play a role in disadvantaged students' feelings of belonging or alienation. However, more research is needed on this topic. Our research also indicates a need for a better understanding of how hierarchized educational landscapes of secondary schooling potentially erode social cohesion when certain professions and educational paths are devalued by students who are likely to have more powerful positions in the future due to the cultural and social capital that they acquire in more privileged schools.

The ethnographic data contain sensitive information and are not publicly accessible. Please contact the authors regarding any questions you might have.

The data collection was carried out by CR. Data analysis was conducted by CR. The writing of the article was mainly done by CR. SL and CR did the conceptualization of the paper together. CR did the revisions of the article. The supervision of the research, project management, and funding acquisition were done by SL. SL revised the paper.

The contact author has declared that neither of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers and the editor Laura Péaud for their comments and their work. The authors would also like to thank Itta Bauer, Lara Landolt, Nicole Nguyen, Norman Backhaus, and Hanna Hilbrandt for their very helpful and constructive comments on earlier drafts of this paper. In addition, we would like to thank Simon Milligan for his professional support with proofreading and language editing and Merit Kägi and Selina Gattiker for help with transcribing the interviews. Our final thanks go to the children, their parents, and the teachers and headmasters who took part in this research.

This research has been supported by the Schweizerischer Nationalfonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung (grant no. 192207).

This paper was edited by Laura Péaud and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Abrassart, A., Busemeyer, M. R., Cattaneo, M. A., and Wolter, S. C.: Do adult foreign residents prefer academic to vocational education? Evidence from a survey of public opinion in Switzerland, J. Ethn. Migr. Stud., 46, 3314–3334, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1517595, 2020.

Bauer, I.: Framing, overflowing, and fuzzy logic in educational selection: Zurich as a case study, Geogr. Helv., 73, 19–30, https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-73-19-2018, 2018.

Bauer, I. and Landolt, S.: Introduction to the special issue “Young People and New Geographies of Learning and Education”, Geogr. Helv., 73, 43–48, https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-73-43-2018, 2018.

Bauer, I. and Landolt, S.: Studying region, network, fluid, and fire in an educational programme working against social inequalities, Geoforum, 136, 11–20, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.08.004, 2022.

Beck, M. and Jäpel, F.: Migration und Bildungsarmut: Übertrittsrisiken im Schweizer Bildungssystem, in: Handbuch Bildungsarmut, edited by: Quenzel, G. and Hurrelmann, K., Springer Fachmedien, Wiesbaden, 491–522, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-19573-1_19, 2019.

Blokland, T.: Mothering, Habitus and Habitat: The Role of Mothering as Moral Geography for the Inequality Impasse in Urban Education, Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12576, 2023.

Boterman, W. R.: The role of geography in school segregation in the free parental choice context of Dutch cities, Urban Stud., 56, 3074–3094, https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019832201, 2019.

Bourdieu, P.: Cultural reproduction and social reproduction, in: Knowledge, education and cultural change, edited by: Brown, R., Tavistock, London, 71–112, ISBN 9781138497689, 1973.

Bourdieu, P.: Outline of a Theory of Practice, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-26346-8, 1977.

Bourdieu, P.: The Social Space and the Genesis of Groups, Theory Soc., 14, 723–744, 1985.

Bourdieu, P.: The forms of capital, in: Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by: Richardson, J. G., Greenwood, 241–258, ISBN 978-0-313-23529-0, 1986.

Bourdieu, P.: The State Nobility Elite Schools in the Field of Power, Stanford University Press, ISBN 9780804717786, 1996.

Bourdieu, P.: The weight of the world, Polity Press, Cambridge, ISBN 0-8047-3845-9, 1999.

Bourdieu, P.: Wie die Kultur zum Bauern kommt, VSA Verlag, ISBN 3-87975-803-4, 2001.

Bourdieu, P.: Bildung. Schriften zur Kultursoziologie 2, Surkamp Verlag, ISBN 978-3-518-29836-7, 2018.

Butler, T. and Hamnett, C.: Praying for success? Faith schools and school choice in East London, Geoforum, 43, 1242–1253, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.03.010, 2012.

Butler, T., Hamnett, C., and Ramsden, M. J.: Gentrification, Education and Exclusionary Displacement in East London, Int. J. Urban Reg. Res., 37, 556–575, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12001, 2013.

Cattaneo, M. A. and Wolter, S. C.: Die Berufsbildung in der Pole-Position. Die Einstellungen der Schweizer Bevölkerung zum Thema Allgemeinbildung vs. Berufsbildung, SKBF Staff Paper, SKBF, 18 pp., https://www.skbf-csre.ch/fileadmin/files/pdf/staffpaper/staffpaper_18_berufsbildung.pdf (last access: 23 October 2024), 2016.

Charmaz, K.: Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis, Sage Publications, London, ISBN 9780857029140, 2006.

Criblez, L.: Das Schweizer Gymnasium: Ein historischer Blick auf Ziele und Wirklichkeit, in: Abitur und Matura zwischen Hochschulvorbereitung und Berufsorientierung, edited by: Eberle, F., Schneider-Taylor, B., and Bosse, D., Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden, 15–49, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-06090-9_1, 2014.

Davidson, E.: Marketing the Self: The Politics of Aspiration among Middle-Class Silicon Valley Youth, Environ. Plan. A, 40, 2814–2830, https://doi.org/10.1068/a4037, 2008.

Flick, U.: Qualitative Sozialforschung. Eine Einführung, Rowohlt, Hamburg, ISBN 978-3-499-55694-4, 2019.

Gamsu, S.: The `other' London effect: the diversification of London's suburban grammar schools and the rise of hyper-selective elite state schools, Brit. J. Sociol., 1155–1174, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12364, 2018.

Gaztambide-Fernández, R.: The Best of the Best, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjnrv46, 2009.

Gaztambide-Fernández, R. and Maudlin, J. G.: “Private Schools in a Public System” School choice and the production of elite status in the USA and Canada, in: Elite Education. International perspectives, edited by: Maxwell, C. and Aggleton, M., Routledge, London, 55–68, ISBN 9781138799615, 2015.

Gerhard, S. and Bayard, S.: Erfolg im Studium. Welche Faktoren den Studienverlauf der Zürcher Maturandinnen und Maturanden beeinflussen, Bildungsdirektion, Kanton Zürich, https://www.zh.ch/content/dam/zhweb/bilder-dokumente/themen/bildung/bildungssystem/studien/erfolg_im_studium.pdf (last access: 23 October 2024), 2020.

Gibson, A.: The (RE-)production of elites in private and public boarding schools: Comparative perspectives on elite education in Germany, Comparat. Social Res., 34, 115–135, https://doi.org/10.1108/S0195-631020190000034006, 2019.

Gold, R. L.: Roles in Sociological Field Observations, Social Forces, 36, 217–223, https://doi.org/10.2307/2573808, 1958.

Hafner, S., Esposito, R. S., and Leemann, R. J.: Transition to Long-Term Baccalaureate School in Switzerland: Governance, Tensions, and Justifications, Educ. Sci., 12, 93–113, https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12020093, 2022.

Halvorsen, P.: A sense of unease: elite high school students negotiating historical privilege, J. Youth Stud., 25, 34–49, https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2020.1844169, 2022.

Harvey, C. and Maclean, M.: Capital Theory and the Dynamics of Elite Business Networks in Britain and France, Sociol. Rev., 56, 103–120, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2008.00764.x, 2008.

Helsper, W., Niemann, M., Gibson, A., and Dreier, L.: Positionierungen zu “Elite” und “Exzellenz” in gymnasialen Bildungsregionen – Eine “Gretchenfrage” für Schulleiter exklusiver Gymnasien?, Z. Erziehungswissen., 17, 203–219, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-014-0529-y, 2014.

Henry, J.: Beyond the school, beyond North America: New maps for the critical geographies of education, Geoforum, 110, 183–185, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2020.01.014, 2020.

Hofstetter, D.: Die schulische Selektion als soziale Praxis Aushandlungen von Bildungsentscheidungen beim Übergang von der Primarschule in die Sekundarstufe I, Beltz Juventa, ISBN 978-3-7799-4441-6, 2017.

Holloway, S. L. and Pimlott-Wilson, H.: Schools, Families, and Social Reproduction, in: Geographies of Schooling, vol. 14, edited by: Jahnke, H., Kramer, C., and Meusburger, P., Springer, 281–296, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-18799-6_14, 2019.

Holloway, S. L., Hubbard, P., Jöns, H., and Pimlott-Wilson, H.: Geographies of education and the significance of children, youth and families, Prog. Hum. Geogr., 34, 583–600, 2010.

Holloway, S. L., Pimlott-Wilson, H., and Whewall, S.: Geographies of supplementary education: Private tuition, classed and racialised parenting cultures, and the neoliberal educational playing field, Trans. Inst. Brit. Geogr., https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12666, in press, 2024.

Holt, L. and Bowlby, S.: Gender, class, race, ethnicity and power in an elite girls' state school, Geoforum, 105, 168–178, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.05.020, 2019.

Kanton Zürich: Kennzahlen von Schulgemeinden, https://Pub.Bista.Zh.Ch/de/Zahlen-Und-Fakten/Andere/Kennzahlen-von-Schulgemeinden/Vergleich-von-Schulgemeinden/ (last access: 17 June 2024), 2022.

Kanton Zürich: Mehr Schülerinnen und Schüler an der Zentralen Aufnahmeprüfung 2024, https://www.zh.ch/de/news-uebersicht/medienmitteilungen/2024/05/mehr-schuelerinnen-und-schueler-an-der-zentralen (last access: 17 June 2024), 2024a.

Kanton Zürich: Gymnasiale Maturitätsquote, https://www.zh.ch/de/bildung/bildungssystem/zahlen-fakten/gymnasiale-maturitaetsquote.html (last access: 17 June 2024), 2024b.

Khan, S. R.: Privilege, Princeton University Press, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400836222, 2011.

Khan, S. R. and Jerolmack, C.: Saying Meritocracy and Doing Privilege, Sociol. Quart., 54, 9–19, https://doi.org/10.1111/tsq.12008, 2013.

Koh, A. and Kenway, J.: Elite Schools: Multiple Geographies of Privilege, edited by: Koh, A. and Kenway, J., Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315771335, 2016.

Kuyvenhoven, J. and Boterman, W. R.: Neighbourhood and school effects on educational inequalities in the transition from primary to secondary education in Amsterdam, Urban Stud., 58, 2660–2682, https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020959011, 2021.

Lillie, K.: Multi-sited understandings: complicating the role of elite schools in transnational class formation, Brit. J. Sociol. Educ., 42, 82–96, https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2020.1847633, 2020.

Lipman, P.: Education and the spatialization of urban inequality: A case study of Chicago's Renessaince 2010, in: Spatial Theories of Education. Policy and Geography Matters, edited by: Gulson, K. N. and Symes, C., Routledge, New York, 155–174, ISBN 9780415882552, 2007.

Merry, M. S. and Boterman, W.: Educational inequality and state-sponsored elite education: the case of the Dutch gymnasium, Comparat. Educ., 56, 522–546, https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2020.1771872, 2020.

Moser, U., Angeline, D., Hollenweger, J., and Buff, A.: Nach sechs Jahren Primarschule: Deutsch, Mathematik und motivational-emotionales Befinden am Ende der 6. Klasse, Bildungsdirektion, Kanton Zürich, https://edudoc.ch/record/95634/files/Lernstandserhebung_6KlasseZH_Bericht.pdf (last access: 23 October 2024), 2011.

Neuenschwander, M. P.: Schultransitionen – Ein Arbeitsmodell, in: Bildungsverläufe von der Einschulung bis in den ersten Arbeitsmarkt, edited by: Neuenschwander, M. P. and Nägele, C., Springer Fachmedien, Wiesbaden, 3–20, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-16981-7_1, 2017.

Nguyen, N., Cohen, D., and Huff, A.: Catching the bus: A call for critical geographies of education, Geogr. Compass, 11, 1–13, 2017.

Parekh, G. and Gaztambide-Fernández, R.: The More Things Change: Durable Inequalities and New Forms of Segregation in Canadian Public Schools, Springer, 809–831, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40317-5_43, 2017.

Persson, M.: Contested ease: Negotiating contradictory modes of elite distinction in face-to-face interaction, Brit. J. Sociol., 72, 930–945, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12874, 2021.

Pfister, A.: Neue Schweizer Bildung Upskilling für die Moderne 4.0, hep Verlag, Bern, ISBN 978-3-0355-2010-1, 2022.

Phillippo, K.: A contest without winners: How students experience competitive school choice, University of Minnesota Press, https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctvdmwx5g, 2019.

Phillippo, K., Griffin, B., Del Dotto, B. J., Lennix, C., and Tran, H.: Seeing Merit as a Vehicle for Opportunity and Equity: Youth Respond to School Choice Policy, Urban Rev., 53, 591–616, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-020-00590-y, 2021.

Reay, D., Crozier, G., and James, D.: White middle-class identities and urban schooling, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-230-22401-8, 2011.

Reh, C. and Landolt, S.: Parental responsibilisation and camouflaging class-based inequalities: an ethnography of a highly selective educational transition, Educ. Rev., https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2024.2342729, in press, 2024.

Savage, M.: Social Class in the 21st Century, Penguin Random House, UK, https://doi.org/10.2501/IJMR-2016-019, 2015.

Savage, M. and Williams, K.: Elites: Remembered in Capitalism and Forgotten by Social Sciences, Sociol. Rev., 56, 1–24, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2008.00759.x, 2008.

Sawert, T.: Das schulische Fremdsprachenprofil als soziale Segregationslinie. Historische Entstehung und gegenwärtige Relevanz der schulischen Fremdsprachenwahl als horizontal differenzierende Bildungsentscheidung, Berl. J. Soziol., 28, 397–425, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11609-019-00381-7, 2018.

Schatzki, T. R.: Social Practices, Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511527470, 1996.

SKBF: Bildungsbericht Schweiz 2023, Aarau, ISBN 978-3-905 684-23-0, 2023.

Stadt Zürich: Anteil ausländischer Wohnbevölkerung, https://www.stadt-zuerich.ch/prd/de/index/statistik/themen/bevoelkerung/nationalitaet-einbuergerung-sprache/anteil-auslaendische-bevoelkerung.html (last access: 23 October 2024), 2022.

Stadt Zürich: Bildungsstand der Wohnbevölkerung, https://www.stadt-zuerich.ch/prd/de/index/statistik/themen/bildung-kultur-sport/bildung/bildungsstand.html (last access: 23 October 2024), 2023.

Steiner-Khamsi, G.: The economics of policy borrowing and lending: A study of late adopters, Oxf. Rev. Educ., 32, 665–678, https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980600976353, 2006.

Streckeisen, U., Hungerbühler, A., and Hänzi, D.: Fördern und Auslesen, VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden, ISBN 978-3-531-15346-9, 2007.

Taylor, E.: `No fear': privilege and the navigation of hierarchy at an elite boys' school in England, Brit. J. Sociol. Educ., 42, 935–950, https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2021.1953374, 2021.

Törnqvist, M.: The making of an egalitarian elite: school ethos and the production of privilege, Brit. J. Sociol., 70, 551–568, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12483, 2019.

Wilson, D. and Bridge, G.: School choice and the city: Geographies of allocation and segregation, Urban Stud,, 56, 3198–3215, https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019843481, 2019.

Yoon, E. S.: Neoliberal imaginary, school choice, and “new elites” in public secondary schools, Curricul. Inq., 46, 369–387, https://doi.org/10.1080/03626784.2016.1209637, 2016.

Switzerland has a federal education system in which the primary responsibility for education lies with the cantons, Switzerland's administrative regions. Zurich has a 6-year-long Gymnasium starting after elementary school, on which this paper focuses, as well as a 4-year-long Gymnasium, starting from grade 9. Some cantons only have Gymnasia from grade 9.

All interview quotations and field notes used in this article were translated from Swiss-German to English by the first author.

Gymnasium teachers usually only teach one or two subjects, in which they have a master degree from a university, while Sekundarschule teachers teach multiple subjects and earn their degrees at universities of teacher education. Gymnasia emphasized in the info events that their teachers, in contrast to Sekundarschule teachers, are true “experts” in their fields.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Public and private elite schools as places of privilege production and reproduction

- Secondary education in the city of Zurich

- Methods

- The transition period: a platform to address students

- Students' perception of the Gymnasia and their students during the transition period

- Discussion and conclusion

- Appendix A

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Public and private elite schools as places of privilege production and reproduction

- Secondary education in the city of Zurich

- Methods

- The transition period: a platform to address students

- Students' perception of the Gymnasia and their students during the transition period

- Discussion and conclusion

- Appendix A

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References